Читать книгу Invitation to Murder - Leslie Ford - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER : 2

ОглавлениеHe saw no reason to revise that opinion Friday afternoon when he came limping up from a culvert with a coffee can full of ditch water to pour into the boiling radiator of his pickup truck stalled on a presumed short cut in the backwoods and rolling green pastures of Virginia. The green Cadillac with a woman and two girls in the back seat, the only mobile unit he’d seen since he left the main road, hadn’t even slowed down when he flagged it to ask the way to Dawn Hill Farm.

“Thought I was a plant hijacker, no doubt.”

He grinned at the New Jersey license plates and the load of freshly dug azaleas in the old truck. They were the reason he was both late and lost. When his sister said she knew a man a couple of miles this side of Charlottesville, a stone’s throw from Dawn Hill Farm, where he could pick them up dirt cheap, he should have known she meant a woman twenty miles the other side, nowhere near Dawn Hill Farm, and the reason they were only a little more expensive than usual was that he’d’d dug and balled them himself. The real folly, of course, had been to let the azalea woman tell him about the short cut.

“Twelve miles from Summerville Court House,” she said. “A green and white mailbox. You can’t miss it.”

He’d give it another mile, Fish Finlay decided. Or if another car came by, he’d stay in the truck so they wouldn’t see him limping. That was the trouble with his leg, he thought, knowing he was being a fool of sorts. Hypersensitivity, they called it. Other people lost worse than a leg in the war, didn’t they? You’re alive, aren’t you? You’ve got a first-rate job, what are you beefing about? You just can’t forget you were an all-Eastern end in your Ivy League days. Nobody gives a damn about your leg . . . it’s your head that counts, old boy. Forget it. And behind the mahogany desk he did forget, and nights and weekends in his place in New Jersey. Only occasionally—at times like this, for instance—did it flash up into his conscious mind.

“Grow up, Psycho. Don’t be a jerk. What’s eating you now?”

Apart from the stalled engine, Caxson Reeves and the azaleas were the answer to that one.

“If you want Jennifer Linton to go to Newport, it’s Anne Linton, not the girl, you’d better see,” Reeves had remarked dryly when Fish reported his diplomatic failure. “And I’d make it as unimpressive and unofficial as possible. Didn’t you tell me you wanted a Friday to go to Virginia and get some bushes?”

He made it sound like a load of stinkweed.

“Azaleas, sir.”

“Then go get them and drop by Dawn Hill casually. Tell Anne Linton we have a serious problem. Keep your mouth shut about Dodo cutting off the stipend.”

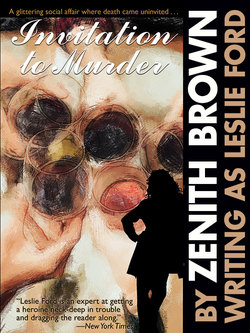

“You can stop that, can’t you? It’s a lousy trick. Or is that sort of thing why we call the Trust ‘I. to M.’?”

That came out before Fish knew he was saying it. He flushed under the bleak eyes looking at him. “M. 5401” was the Bank’s listing of the James V. Maloney Trust. “I. to M.” was a top-echelon joke that Fish Finlay never should have heard and having heard never repeated. “I. to M.” stood for “Invitation to Murder.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” he said.

“It so happens that the term ‘Invitation to Murder’ has nothing to do with the Maloney Trust as you know it, Mr. Finlay,” Caxson Reeves said evenly. “It refers to a document that James Maloney drew up and signed the morning he walked out of here for the last time. It is concerned with the disposition of the Trust in the event of the death of both Dodo Maloney and her daughter Jennifer Linton before Jennifer is twenty-two years old. It also happens to be my business, not yours.”

“I’m sorry,” Fish said again.

“Very well.” Reeves got up and locked the conference room door. “To get back to what is your business. I think it’s time you know more about the Maloney Trust. But first—if Dodo wishes to cut off her daughter’s stipend, there’s nothing we can do about it. That’s the way James V. Maloney wrote the Trust.”

He looked impassively down at the empty chair at the other end of the table.

“He sat right there, and dictated to me.”

He was silent for an instant, his eyes fixed on the chair.

“Jim Maloney was a bitterly unhappy man,” he said deliberately. “It may be he was crazy. I never thought so. He knew he had the Midas touch. He parlayed a small inheritance into a large fortune. He married what you might call a girl of the people so he could have a large and healthy family. It was the only thing he wanted. He thought he didn’t have it because it was God’s way of making him pay for the Midas touch. Then he learned that it was only his wife’s vanity and social ambition, and he learned too that Jennifer was the only grandchild he was going to have. Dodo had been through a blatant divorce and a damned unpleasant custody fight for Jennifer, and was embarked on another equally blatant romance. It was then, when he was sick of everything, that plants came into Maloney’s life to remake it, through these two old gardeners at Enniskerry.”

He nodded at the framed airview photograph of the Maloney estate at Newport that concealed the wall safe behind the chair where James V. Maloney had sat.

“That’s why Dodo has the place there and can’t get rid of it—except to let it go to the city of Newport. He endowed it, so she couldn’t toss those two out of their jobs and their gardens.”

He pulled his half-spectacles down over the bridge of his nose and sat gazing intently at the photograph.

“He was talking about Dodo and her daughter that day. A weed in rich soil takes nourishment from a useful plant. If the plant grows, it flowers quicker to make the best of what life it has. Jim Maloney thought Dodo was a weed. He gave her until Jennifer was twenty-two to prove she wasn’t. His theory was that Jennifer, struggling against her environment, would flower into a useful life. He didn’t put it that way, but that was the gist of it. Jennifer could sink or swim. When she was twenty-two, Dodo Maloney would get back from her precisely the treatment she’d given her. On that basis, it’s been my job to help Dodo cut her own throat any way she likes . . . which she’s done her damndest to do ever since I can remember.”

He got up. “What contribution her fourth husband is going to make, I don’t know. What Dodo told you this morning she’s told me. I don’t believe any part of it. As you know, I first heard about this marriage from a gossip columnist calling up to find out how much money she’d settled on de Gradoff. I’m skeptical of chance romantic meetings.” A wintry gleam came into his eyes for an instant. “In my book, anyone pretending he has no interest in money is either a fool or a knave. And rather particularly, in the present case . . . in view of an item that came in the mail this morning, while Dodo was telling you her happy story.”

He went to the end of the table and took the photograph of Enniskerry off the wall. He put it on the table, opened the safe, brought out a pale-blue airmail envelope and took a sheet of typed paper out of it.

“This is either in good faith, or it’s a clumsy attempt to find out the provisions of the Maloney Trust. Not even my secretary knows them. I promised that to Jim Maloney. Dodo knows them, but it’s to her interest to keep quiet. Jennifer was told them on her sixteenth birthday. You know them. I’m getting older, and I don’t think I’ve misjudged you.”

He pushed his spectacles up in place and looked down at the paper.

“This is from our Paris correspondent. He says it is a ‘friendly exploratory inquiry,’ on behalf of an undisclosed principal, and in no sense a demand for money. The undisclosed principal wishes to know what progress we are making with our program for paying the outstanding obligations of the Countess de Gradoff’s husband, Count Nicolai Hippolyte de Gradoff.”

“He wishes to know what?”

“When we are going to pay de Gradoff’s debts.” Reeves’s voice was as dry as the crackle of the paper as he put it back in the envelope. “I made a transatlantic call. Off the record, I was told that de Gradoff was heavily involved when his first wife died.”

“Killed herself.”

“I’m purposely restricting myself to what has been reported to me as fact,” Reeves said quietly. “—To clear himself, de Gradoff borrowed a considerable sum on his interest in the first wife’s estate. It is that sum this so-called ‘friendly inquiry’ is about. The undisclosed principal was given to understand that he was marrying a rich American lady . . . at which time the debt would be paid.”

He put the letter in the safe, closed it and hung the picture of the many-towered mansion back on the wall. There was no ripple of expression in the dusty aridity of his face or in his voice when he spoke again. “Perhaps that is why de Gradoff appeared anxious to hear what you might have to say to Dodo this morning.”

Fish looked at him soberly. “Do we have any program—”

“None. I have no authority to pay such debts. If Dodo wishes to do it out of income, that’s her business. I advised the ‘undisclosed principal’ to take the matter up with her.”

As Reeves gathered up his papers, Fish got to his feet. “One other point, sir—if I may stick my neck out again.”

“Why not?”

“This French detective that Dodo—”

“You told me.” He looked at his watch. “It would seem to indicate that there’s a second ‘undisclosed principal’ making inquiries. But I have a meeting.”

He went out leaving Fish Finlay standing there much the way he was sitting now in the stalled truck, the problem that seemed simple on the face of it complicated by a feeling of uneasiness he could not define. He looked at his watch. It was ten minutes to five . . . late to drop in on anybody in the mint julep belt in the rig he was in. He was aware suddenly that he was in honest fact procrastinating and had been all day. He could have got half as many azaleas and had plenty of time to get to Dawn Hill Farm earlier, if he’d wanted to.

“You don’t want to let Dodo down . . . but you don’t want to force the kid to go to Newport. Make up your mind, Finlay.”

It was ten to one he’d passed the green and white mailbox without seeing it for the simple reason he didn’t want to see it. He started the truck. He’d give the rolling landscape one more roll and the empty road two more curves, and then backtrack. It was around the second curve that he saw the boy perched on the white culvert down in the hollow. He rattled down, braked the truck, leaned over to ask the way to Dawn Hill Farm, and saw it was not a boy. It was a girl in a white shirt and green jodhpurs, her green jacket and black velvet cap in a dusty heap on the road at her feet, and it was about as miserable and dejected a little figure as Fish Finlay had ever seen.

He grinned, looking across the road up to the open field.

“Lost a horse, sis?”

Then he braked the truck sharply. He couldn’t see the kid’s face, just the top of her dark tousled head, but her shirt was badly torn and her fists clenched tight.

“You’re not hurt?”

She shook her head. “I didn’t have a horse.” Her voice was strained, as tight as her fists. She raised her head then and Fish saw her face.

A feather of gold dropped from the wing of an angel there in the dusk. His hand stopped motionless on the door.

She wasn’t a kid. She was a girl, or maybe not a girl but a dream half-dreamed, only seeming real there in the golden dusk . . . the heart-shaped face, moon pale, the wide-set stricken eyes, dark gray-green under thick glossy brows and long black curling lashes, full lips with no lipstick to hide their pallor, nothing to hide the intense unhappiness that shot like a poignant arrow through the futile armor of Fish Finlay’s own unhappy heart.

She got up from the culvert and he saw her slim lovely body, high young breasts, girl and lost dream melted into one, as she stood looking at him for a moment of relief as poignant as her distress, and then picked up her jacket and cap and came over to the truck.

“Will you take me up the road as far as you’re going, please?” she asked. She brushed off her torn shirt sleeve. “I came through the woods, that’s why I’m such a mess. Some people dropped me, but they’ve gone. And I’ve got to get away.” She looked at the load of shrubs in the back of the truck. “Unless you’re delivering those around here? I could wait if you’d come back. . . .”

Fish Finlay pulled himself sharply out of his trance-shock.

“Sure,” he said. “Hop in.”

“Oh, good!” She ran around the front of the truck, yanked the door open before he could reach over to open it for her, climbed in and slammed it shut, an old hand at battered trucks.

“I’m so glad.” She sank down in the broken springs and skinned her hair back. “I didn’t know whatever I was going to do.”

“Where do you want to go?” He knew he sounded churlish, but he couldn’t help it.

“Westminster. About ten miles. Where are you going?”

“New Jersey.”

“Oh, good. It’s right on your road, this way.”

She glanced at his earth-stained paratrooper boots and back at the plants.

“Those are azaleas, aren’t they?”

“Right,” he said, trying to start the damned engine again, with another hill to climb. She was waiting, taut till it started, and when she didn’t relax, then he knew it was something else she was waiting for, as the truck made the grade around a steep bank of honeysuckle, dogwood above it. She turned her head painfully, looking across in front of him.

“Our house is up there, that’s our lane. Oh, watch it, the frost boils are awful.”

“Sorry.” Finlay steadied the truck. It wasn’t the frost boils. It was the green and white mailbox at the mouth of the lane. White with green stenciled block letters. Dawn Hill Farm. But it couldn’t be. It wasn’t possible. There must be another house up the Dawn Hill lane.

She was silent for a while, lost in her own unhappiness again, before she roused herself.

“Are you a gardener?” she asked. “I don’t mean that. Gardeners are all so old. But do you work for one?”

“Like a dog,” Fish said.

She glanced at him again. “Or maybe you’re like my grandfather. He was a . . . a horticulturalist. But probably not, he was supposed to be crazy. My mother says so. He just disappeared one day.”

Finlay kept the truck steady. There might be another house on the Dawn Hill Road. There couldn’t be another girl living on it who had a crazy disappearing horticulturalist grandfather. Snap out of it, brother. It never was, it could never be. It was just an error in the golden dusk.

“My stepmother doesn’t think so.” Her voice was unsteady for a moment. “She thinks he just got sick of everything. But she loves gardens. My mother hates them. She says old men plant trees, young men dream dreams. But you plant trees, don’t you, or shrubs, anyway?”

“Or don’t I dream dreams? Is that what you mean?”

“Sort of, I guess.”

The maimed shadow of an old smile limped across Fish Finlay’s homely face, rekindling the memory of far-off unhappy things that for one enchanted moment back there on the empty road he’d forgotten, and that the shock of her being Jennifer Linton had brought painfully back to him. That there’d been a time when dreams were his to dream, back when he didn’t know an azalea from a privet hedge, and the brightest of them all had been another girl, a golden girl with amber eyes. And what he’d never told anybody, that it wasn’t because he’d been an Ivy League end that he couldn’t take his leg in his stride and had holed in, an old man planting trees. It was what the dream girl had said, as kindly as she could, about a golden girl tied to a junk heap: I’m a pig, darling. I’ve tried to be noble but I’m really not. We’re just wrong for each other now. We couldn’t ever have any fun any more. Not our kind of fun. Somebody’ll come along, darling, somebody who loves to sacrifice. . . .

“No,” Fish Finlay said. “I banished dreams.”

To hell with dreams. To hell with sacrifice. His jaw tightened. The angel reaching sadly down picked up the golden feather in the dust.

Jennifer Linton was silent. He brought himself abruptly back to the job in hand and glanced sideways at her . . . the recalcitrant daughter of a lovely mother, granddaughter of old James V. Maloney, supposed to flower, if possible, scrabbling what nutriment was left in the shade of the lush luxuriant weed. Assistant Trust Officer Finlay’s problem. He saw her again, simple and lovely, the aura of springtime in April about her.

The pale half-moon of her face was grave.

“You don’t banish dreams,” she said, her voice as grave. “They blow up, when you’re not looking. They blow to pieces, right in your face.” She laughed unexpectedly then and rubbed her nose quickly, like a child. “I know. It’s what happened to me, just now.”

“A dream blew up?”

“With a bang. I live with my stepmother, because my parents were divorced. My father was killed in a car accident, two years ago. And my mother . . . well, she can be. . . . Anyway, she said I had to come to Newport this summer. But I hate it, and she’s so . . . so hard to get along with, anyway. So I wasn’t going to Newport no matter how much of a row my mother made. I was going to stay with my stepmother. Then today I got a cable. I didn’t have to go to Newport. My mother’d changed her mind from the other day when she called me up . . . right when I was 6-2 in the match set for the school cup, so I had to lose by default. And she said, ‘Go back to your silly game.’ ”

She laughed a little. “I guess it’s funny, anyway.”

“It wouldn’t be to me,” Fish Finlay said.

“Me either. Anyway, she changed her mind, and I didn’t have to come to Newport. It was wonderful. That’s why I’m in these clothes, I didn’t take time to change. One of the girls’ mothers was there with a car, coming down this way, so I dashed home. I thought Anne—that’s my stepmother—would be as glad as I was.”

“Wasn’t she?”

Jennifer Linton didn’t answer for so long that he glanced over at her and saw her still shaking her head, her lashes moist.

“I’m sorry,” he said, disappointed some way.

“I didn’t tell her,” she said then. “There was a . . . a man there. An old friend of all of us. I sneaked in—kid stuff, I guess. You know . . . Big Surprise. He was there, talking to her . . . telling her how much he loved her, and how tired he was of waiting and . . . seeing her struggle, trying to hang on to the farm for . . . for somebody else’s spoiled brat—that’s me—when she ought to have a life and children of her own. I . . . I was just stunned, I guess.”

She took a deep breath.

“I was so stunned I couldn’t get out, and so I heard her say she loved him too but she wasn’t going to break up the only home I had till . . . till I got myself a job and got squared away, just when I’d got myself together and had some confidence in myself and the fact that somebody really wanted me around.” She paused a moment. “I just never thought about Anne getting married. I guess my mother’s been married so many times I thought it was enough for everybody. And this man’s terribly nice and has money enough to . . . I was just stupid. But it was a shock. You bear right at the next corner.”

She was silent for a moment.

“So I’m going to Newport,” she said, calm again. “It’s funny. I get some money some day, and I’ve been planning all the things I’d do for Anne. Pay the mortgage on the farm, and that sort of thing. She’s done so much for me. And here all the time she could have had . . . everything. I was just sick. And on the road, I was terrified somebody I knew would come along, and she’d find out I’d been home. She’d feel awful if she knew I’d heard. And she knows how I . . . I don’t like this new husband of my mother’s.”

“Why not?” Fish Finlay asked.

“She thinks it’s because my mother didn’t even tell me she was getting married, this time, and one of the girls heard it on a radio gossip program. But that’s not it. It’s what another girl at school told me about him. Her father’s a diplomat in Washington. They’re from the Argentine.”

Fish Finlay concentrated silently on the road.

“This new husband was married before to a cousin of theirs. And she was supposed to have killed herself.”

A sudden sharp chill froze the base of Finlay’s spine.

“Supposed to?”

It came out more casually than he’d dared to hope.

“That’s right. But the family doesn’t think she did. This girl says they know, in fact—that she didn’t kill herself.”

Finlay’s spine was not chilled at the base, it was stone-cold deep up into his cerebrum. “You don’t mean—”

He caught himself. This was fantastic.

“It isn’t me,” she said. She spoke with a literal realism, so clear-eyed and without emotion that it made her seem at once both older and younger than he knew she was. “It’s what the girl told me. She says they knew she didn’t kill herself. She doesn’t know how. It was just things she overheard.”

Dear God . . . she can’t possibly know what she’s saying. He slowed the truck down, his eyes glued to the road.

“She said they fought like tigers to keep her from marrying him. Then when she died, they found out something. This girl isn’t sure what. But they didn’t want a scandal. Or maybe they didn’t have actual legal proof. But they could see he didn’t get anything out of it. And he didn’t . . . not her money, or even her personal stuff. Not even her furs. This girl has a coat of hers. It’s beautiful, but . . .”

She shivered a little, the only sign that she knew the meaning of what she’d said.

Fish slowed down again and looked around at her. There was no ripple on the opaque mask she’d drawn over her face since the naked moment back on the culvert.

“Now look,” he said, as quietly and soberly as he could. “You don’t seriously believe all this, do you?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “This girl swears it’s the truth. My mother knows he didn’t get any of her estate. But the story she’s heard is different. I know, because I tried to tell her, in Nassau last winter, when she had me down to meet him. So I shut up. I was afraid, anyway. And he doesn’t like me to begin with . . . any better than I do him.”

“You didn’t tell her—”

“I didn’t even get started, really,” she said calmly. “She cut me off with a lot of corny stuff. He’d told her his story and she believes it. He’s smart.”

“You haven’t told anybody then.”

“No. And I don’t know why I’m telling you, except that I felt so horrible. And I’m glad I did, because you’re probably right. It does sound crazy. You see, I’m not worried about my mother, because she doesn’t have any money to leave anybody. Unless something happens to me, before I’m twenty-two. Or unless she hasn’t told him she just has income,” she added.

As indeed she hasn’t.

“Because she’s funny about money. Terribly generous if it’s something she wants you to have, not five cents if she doesn’t. Like iron. Her last marriage went on the rocks over some fishing tackle. But maybe this one’s smarter.”

The wheeze and rattle of the truck intensified her silence and Fish Finlay’s.

“I was going to tell my stepmother,” she said then. “But she’d have worried. She wouldn’t let me go to Newport now.”

“She’s be right,” Fish said. “You mustn’t go.”

“And mess up Anne’s life still more?” she demanded warmly. “How can you say that? Except that you don’t know, of course. I haven’t explained it very well. No. I’ve got to go. There’s nothing else to do. That’s all there is to it.”

If Fish Finlay couldn’t see it, he couldn’t help hear it in the sudden passionate sincerity of her voice.

They were passing a service station, coming into the small town. She flashed up in the seat. “Oh, heavens, we’re here already! What’ll I do? What’ll I tell them?”

He smiled a little in spite of himself. Suspected murder she could take. This was different.

“Oh, I know!” She flashed around toward him. “Oh . . . would you? Would you sell me a couple of your azaleas? The house proctor has a green thumb. I could tell her I went after them for her. Just one lie would cover it. I don’t want them to call up Anne!”

“Sure,” he said.

“Except that I haven’t any money till next month. Or you could send the bill to the Bank. Mr. Reeves might—”

“Pay me later,” Fish said. “I’ll be back.”

“Oh, wonderful! The brick gate right there. . . .”

He turned the truck in.

“We go left to the service yard.”

Fish shook his head. “You hop out here. I’ll take the trees, and find the old man to plant them.”

He smiled at her and stopped the truck. She was out and around before he was. They met in front of the battered fender. Her eyes were shining as she put her hand out.

“I don’t know how to thank you! Really, thanks ever so much!”

She turned and ran up the lawn toward the quiet mansion on the hill, and stopped, looking back, her eyes like breathless stars, their light transformed instantly to a new and lovelier compassion as she saw him limping back around to the other side.

“Oh . . .” she whispered. “That’s why he’s banished dreams.”

She turned and ran on until she heard the truck rattle to a start. Then she turned and waved. He said he’d be back.

Fish Finlay had forgotten his leg, then and when he found the service yard and helped the old man unload the azaleas, all of them . . . all he had to give for a momentary dream he was sealing up in a heart where dreams were banished. Jennifer Linton was his job.

“She’s not going to Newport.” He said it out loud as he stopped the truck a moment at the end of the service lane. Suspicion was enough, whether the Argentine girl’s story was true or false. The fact that there was that story settled it.

But he couldn’t turn back and go to Dawn Hill Farm now and tell Anne Linton. Not with the passionate conviction of her protest still in his ears. There was plenty of time. Three months, practically. The de Gradoffs wouldn’t be back home until the middle of June. He switched his lights on and turned the truck northward home.

Crossing the bridge over the Chesapeake he came into the rain. The long gray arms of the fog rose, swirling, beckoning him on, concealing a harsher surf-beaten shore and a golden sandal thrown back from the crest of a hungry wave, the infernal Rock and the grave fit only for a monster, as death and a motley crew assembled in Newport, faces yet unknown, and the hands of the gilded clock on the stable tower at Enniskerry moved silently, marking the hours.