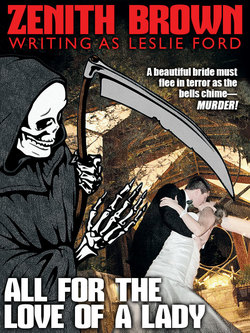

Читать книгу All for the Love of a Lady: A Col. Primrose Mystery - Leslie Ford - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

Оглавление“Is somebody coming?” Molly asked quickly.

“It’s rather late for visitors.”

I looked at the clock on the desk. It was twenty minutes to twelve.

“I’m going up,” she said. “If it’s anybody for me, I’m not here. Please, Grace. And you don’t know where I am.”

She slipped off her shoes and disappeared. I could hear the step half-way up that always creaks, and her door close softly, as I waited for the doorbell to ring. Sheila gave an impatient high-pitched bark and scratched at the door. It wasn’t like her at all, and in that otherwise completely silent house it was a little disturbing. The doorbell isn’t hard to find, and if it were there’s a knocker there.

I went out into the hall and switched on the overhead light. I tried to tell myself it was probably someone not wanting to ring the bell at that time of night if I’d gone upstairs, and I knew no lights were visible from the street, with the old-fashioned solid wood shutters locked and barred in the dining room windows. I turned on the outside light, however, and reached out to take down the chain Molly had put in place when Randy had gone. As I touched it Sheila gave such a savage growl that I dropped it instantly.

It may be absurd to endow a dog with an intuition of danger, but when you’re alone—except for a colored cook wrapped in primeval slumber downstairs—you come to depend on their acuter senses. Anyway, it would have taken more courage than I had just then to have opened that door. I switched off the hall light instead, slipped into the dining room, unbolted the shutter on the farthest window, and opened the flap enough to peer out.

There wasn’t anybody on the front stoop at all, or anybody that I could see in the radius of the light reaching out under the trees.

I closed the shutter and went back to the front door. Sheila was still sniffing and whining. Perhaps it was just a cat she didn’t like, I thought. I turned the bolt and opened the door. She shot out in front of me, growling. I looked quickly along the street. The red tail lights of a car going a little on the diagonal straightened and went on as she dashed down the steps, nose to the bricks, following a scent that brought her to an abrupt stop at an open place on the curb four houses down. She sniffed around and came back to it, and back to the door again. I watched her, completely bewildered, as she went back to the curb, and suddenly lifted her head and howled. It was that long low howl that some people think is a warning of death . . . reeking in a dog’s nostrils before mortals are aware of its chilling shadow lengthening across the doorway. I don’t believe that, but I shivered a little, thinking that Lilac might hear it, and remembering her agony when a picture fell, long ago, one evening just at dusk, and the next day two little boys and she and I began to carry on by ourselves in that same house.

I also found myself glancing down the block and across the street at the yellow brick house where Colonel Primrose lives. Seven generations of John Primroses have been born and lived in that house, but fortunately only one of Sergeant Bucks. I don’t know where he was born, or if he was born at all. It’s hard to imagine he was ever a baby lisping at his mother’s knee. It’s easier to think of him as hacked full-grown out of a stone quarry. Still, it was always rather comforting to know they were both just across the way.

Or it was until I remembered they weren’t there. They’d gone out of town on account of the heat. Or that’s what Sergeant Buck told Lilac, and the newspapers ostensibly confirmed it. It was the first time, however, I’d ever heard of Colonel Primrose announcing his holidays publicly, and since his job is that of a special and apparently unofficial investigator for various of the Intelligence branches, it’s always a little hard to tell. All I know is that he once gave me a telephone number I was to learn and destroy, so that if I ever needed him and he didn’t appear to be at home I could get him. I’ve never used it, but I thought of it now as I whistled for Sheila.

She came reluctantly back, and I pulled her inside and closed the door, double-locking it and putting the chain up, to keep something dark and amorphous that Sheila still felt—and that I was beginning to feel—out of our lives if I could.

I turned off the sitting room lights and went upstairs. Molly’s door was closed. I opened it quietly, so she could get whatever conceivable breath of air might possibly stir a little later. There was none just then. I opened the door from the front bedroom through the bath into her room, and looked in. She was lying on top of the turned-down muslin spread, fast asleep, the moonlight from the open windows over the garden streaming full on her. My heart felt cold for an instant. Then I realized how jittery I really was. It was the silver glow of the moon that made her look so strange and not of this earth. The light that glistened on her upturned face was from the tears that hadn’t dried as she’d cried herself to sleep. She was still fully dressed, one shoe on and the other half falling off the foot of the bed. Her bag was still unopened on the luggage rack in front of the fireplace.

I turned away. She might try to be as cold-blooded as Courtney Durbin probably was, and as Cass Crane appeared to be . . . but it was going to take a lot of the now classical blood, sweat and tears.

Something half waked me once, after I got to sleep. It sounded like a shoe dropping, and I remember thinking vaguely of Molly’s shoe on the edge of the bed, and that I should have taken it off and put it on the floor, before I turned over and went back to sleep to the monotonous whirr of the electric fan out in the hall. Then something waked me again, I don’t know how long after. I opened my eyes and lay there listening, unable to sort out the disturbed realities of the borderline worlds merging into each other. Then I sat up. The downstairs phone was ringing. The one on my bedside table I’d turned off, so I could sleep in the morning when it was cool. I reached out, picked it up and said “Hello,” knowing, some way, before I did, that it would be Cass Crane.

“Grace?” a voice said.

It wasn’t Cass. It was Randy Fleming.

“Look, Grace. Is . . . Molly all right?”

With the illuminated hands of the clock on the table standing at ten minutes past three, not even the overtone of acute anxiety evident across the wire kept me from a sharp feeling of irritation. I could be sympathetic enough with Randy’s concern for her, and think it was sweet, in the daytime. To be waked up by it in the middle of a filthy hot night, with no telling when I’d get back to sleep again, was something else.

“She’s perfectly all right,” I said, trying not to sound as annoyed as I felt. “She’s fast asleep, and so was I. Now will you please go to bed, and don’t worry.”

Then I said, “Have you heard anything from Cass?”

I don’t know why I thought he might have, or why I asked it, except that I was wide awake and curious.

“Yeah,” he said shortly. “In fact, I’ve seen him. Sorry I woke you. Good night.”

His voice couldn’t have been more abrupt, nor could the phone zinging away where his voice had been. I put it down and sat there, hot, sticky and pretty mad. I knew if I turned on the light and tried to read I’d have a thousand bugs sifting in through the screen, so I kicked off the sheet and lay down again. After a few minutes I sat up, something sifting in through the screens of my own mind. Whether it was the anxiety in Randy’s voice, or a feeling I’d been too short with him, I don’t know. Anyway, I got up. The phone might have waked Molly, and she might have heard Cass’s name.

I turned on the light and went out into the hall. There was no sound except Sheila’s tail thwacking against the floor down the hall when she heard me. I looked at Molly’s door. It was closed, so she probably hadn’t heard the phone at all. I started back to my room. The heat was so oppressive, however, that I changed my mind and started downstairs, where it would be a little cooler.

Perhaps it was the fact that Sheila was sitting in front of the door, when she usually spends the night sprawled out on the hearth stones, that made me notice the chain had been moved . . . or it may have been that the light glinted on its polished links hanging down instead of looped up in the socket. I stopped half-way down the stairs, looked up at Molly’s door, went back up, opened it quietly and looked in.

The bed was empty and she was gone, her bag still on the luggage racked in front of the fireplace.

That, I thought, was that. A couple of hours of sleep had done its job, and she’d gone home to Cass. I realized then that that was what I’d been counting on. And I was more relieved than I’d thought I’d be. It’s always such a mess getting mixed up in other people’s domestic quarrels. And Molly belonged with Cass. She must have been acutely aware of it, waking up and lying there alone, before she slipped out through the darkened streets and back to him.

The air probably just seemed fresher and lighter as I went back to bed. It was certainly hot enough the next morning. I woke up with the sun streaming through the windows and Lilac’s heavy step plodding up the stairs. She wasn’t muttering darkly to herself, so we were headed for a peaceful day, I thought as I sat up and looked at the clock. It was ten minutes to eight. I turned to smile at her polished ebony face in the doorway; and my jaw dropped, but literally, as I stared blankly past her.

Molly Crane was there in the hall. She was dressed in her blue nurse’s aide uniform, with her hair brushed up on the top of her head, the curling tendrils around her neck still wet from the shower. Her suntanned face was fresh and lineless, her lips bright red and smiling. Her amber eyes were a little pale, but it could so easily have been the heat that for a moment I wasn’t sure it hadn’t affected me myself.

She laughed. “Don’t tell me you forgot I was here. I tried to be as quiet as I could.”

I didn’t know what to say, under the circumstances. She obviously had no idea I knew she’d been out, and apparently had a definite reason for wanting me to think she hadn’t. It was very confusing. But she didn’t wait for me to answer.

“I’ve got to be at the hospital by eight-thirty,” she said. “If . . . anyone should call me, will you tell them I’ll be back after lunch? If I may come back . . . do you not mind, really?”

Lilac stopped closing the outside shutters. “No, child, Mis’ Grace she don’ mind. It’s company for her. She like company in the house.”

As I didn’t need to say anything, with Lilac taking over, I just smiled.

“Goodbye, then—I’ll see you,” Molly said. She went out, Lilac following her.

I poured a cup of coffee, turned on the portable radio on the table for the eight o’clock local news, and glanced through the comic strips waiting for it to come on. When it did come there wasn’t much I hadn’t heard the evening before. I turned to the gossip column. The last paragraph stood out from the rest of it.

“We can hardly call it this column’s scoop, because it’s what everybody’s been saying since they caught their breath again. But unless our crystal ball is cloudy with the heat, we see a low pressure area reaching as far west as Reno. Some people say he forgot to tell her he was coming back last night, but he looked cheerful enough when we saw him being met by one of the Capital’s coolest looking lovelies . . . who may, of course, just have happened along. You know how airports are, these days. You’re apt to run into most anybody.”

I turned the page and took up my orange juice, half listening to the commercial reporter announcing that the Snow White Laundry was discontinuing pickup and delivery and would take no more new customers, and Fur Storage Inc. had no room for more furs or woolens. You know how it is . . . the radio goes on, and your inner ears are partly closed. Then mine were abruptly open.

“. . . corner of 26th and Beall Streets in Georgetown this morning,” the voice was saying.

I put my glass down and sat up, trying to grope back into the lost ether for what had gone before.

“—The police were called by a paper carrier who noticed the front door standing open and looked inside. The body was taken to the Gallinger Hospital, where the cause of death will be determined. Officers of the Homicide Squad said there was no evidence of violence, but the circumstances surrounding the case were such that an investigation will be made. If you are unable to find your usual supply of Mullher’s Five-X Beer at your dealer’s . . .”

I switched off the dial and sat there, staring blankly in front of me. I couldn’t bring back the words I’d missed . . . but I could hear Randy Fleming as plain as if he were in the room speaking to me. And I could hear the tone of his voice. “Yeah . . . In fact, I’ve seen him . . .”

“—Mis’ Grace?”

I looked around with a start. Lilac was in the doorway.

“Mis’ Grace—Colonel Primrose, he downstairs. He says, don’ you hurry yourself none, but he want to see you if it ain’ inconvenient.”