Читать книгу Road to Folly - Leslie Ford - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

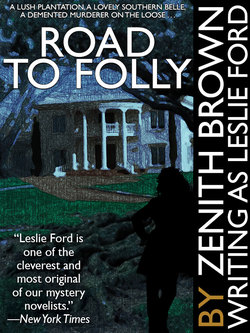

ОглавлениеAhead of us for half a mile stretched an overgrown cavern of live oaks hung with cascades of pale wisteria and thick festoons of grey moss that were more shadow than substance in the low slanting planes of the evening sunlight through the young-leafed branches. Somebody had said the live oak avenues were like cathedral naves. This one wasn’t—it was too impeded with magnolias and holly and snowy dogwood and cassina that had seeded themselves among the old trees and stretched up, seeking the sun. But the grey moss and purple wisteria, and the whole glow and loom were very like the clouds of incense from the high altar of Chartres, with the amethystine lights round it making planes as tangible and solid in the darkened aisles as these planes were intangible and ethereal. The broad aisle itself was overgrown with lush green grass, and where the water had settled in the ruts there were tiny iris and white violets. And it was silent . . . so silent you could hear the wind whispering softly in the pine-tops beyond the oaks, like the insistent murmur of long dead voices.

Jennifer put her foot abruptly on the gas. The engine whirred. Half way along the avenue the white tail of a doe flashed, and then another, and another. Still she didn’t speak, as we rattled over the bumpy road that was scarcely a road as much as narrow tracks across an overgrown lawn. And then, under the pale mauve canopy of moss and light and wisteria with its arabesque of waxy dogwood, I saw the six slender columns of the portico of Strawberry Hill.

As we came closer the silence came again, so profound that it drowned the cough of the engine and made it impudent and easy to ignore. I glanced back. The avenue closed in, opaque and shadowy as a column of amethyst quartz behind us. Jennifer stopped the car in a drive that would have been scarcely definable if it hadn’t been for the marble pedestal that marked the center of it. On the pedestal were two exquisitely lovely marble feet, the heel of one raised just a little, as if a nymph had poised a moment, and two fragile ankles, and nothing else.

Jennifer’s eyes followed mine.

“The war,” she said briefly. “But they didn’t burn the house, or loot it either.”

She looked at me with a little frown, as if she were remembering something. But it passed quickly and she got out of the car.

I stood for a moment on my side, looking up at the slender columns of the portico. This house was dead. The four deep windows on either side of the broad front door were barred and shuttered. The door itself looked as if it had never opened. The steps up to it had rotted at the ends, the graceful wrought-iron balcony over it sagged a little. The narrow palladian window with a bunch of strawberries carved in the key over the center arch was shuttered on the inside. The three broad windows upstairs on either side of it were shuttered too.

For a moment we both stood there. My heart throbbed against my ribs. It was so desolate and blind and tragic, someway, with an eerie silence stretching from the tomb of years. I looked at Jennifer. She was looking me squarely in the eyes, and yet way past my eyes, deep inside me—tragic herself, but very young, and with the kind of defences that only the young trust in.

I heard my voice, quite loud because there were no other sounds, say,

“I think I’d rather go back, Jennifer.”

I don’t know now why I said it. I’m sure I never intended to. It was almost as if I already knew the secret of that old blind house . . . the secret this child had tried so desperately to guard.

She shook her head.

“I didn’t want you to come, but you’re here now. You can’t go back . . . not now. Shall we go in?”

Her voice was perfectly calm, but I saw the corners of her mouth tremble. I followed her up the steps. She unlocked the broad dingy-white door with a big iron key and pushed it open. It was cold inside, cold and damp. I stepped over the threshold. My foot on the side cypress boards, scrubbed clean but not polished, sounded loud and hollow. Jennifer closed the door quickly behind her and drew the bolt. The hall was wide, and even darker than I’d known it would be. The only light was from another palladian window where the delicate sweeping staircase made a balcony across the other end. The door under the stair balcony was closed, an iron bar fastened securely across it. In the dim light from the upstairs window I could see the bold simple cornice and panelling—dingy and split in some places but very fine—and four handsome doors, two on either side with a carved urn of strawberry leaves and blossoms and fruit between the curling rosettes of their broken pediments. It was a fine interior, not as overelaborated as many Low Country houses but bold and masculine . . . not of the diddling Adam that was so popular in Carolina. I glanced quickly at the furniture in it, and saw what Phyllis meant. It was quite perfect. The Chippendale console table with reeded legs, the tarnished girandole above it, the Sheffield urn full of camellias in the center . . . and one of the set of ribband backed Chippendale chairs beside it. I didn’t blame Phyllis for wanting it or even for trying to get it, actually. Or the Sheraton sofa against the opposite wall with the relief of rice sheaves carved on the back. Or the Sully portrait hanging over it. Or the Aubusson rug with its trailing border of strawberries that must, I realized, have been woven especially for that space.

Jennifer pulled off her hat and tossed it with her car keys on a Chippendale chair beside the table. “If you’ll sit down a moment, I’ll see if my aunt is awake,” she said evenly. I walked across the hall and sat down in the sofa, something vaguely disturbing nagging in the back of my mind. Jennifer went quickly along the hall, and ran lightly up the stairs. I heard the rapid tattoo of her heels deaden and disappear.

I glanced at the closed doors into the shuttered rooms, and got up. I don’t think I intended actually opening the one nearest me, though I know only too well how thin the veneer of civilization is on a professional decorator. There was something else in my mind . . . or possibly, I told myself, it was only to get off the horsehair sofa, that always makes me appreciate the fortitude of the people who wore shirts made of it for their sins, that I got up. Then I sat down, abruptly—for my own sins or Phyllis Lattimer’s, I’m not quite sure which.

A door under the stairs was opening, so quietly and so slowly, and without visible human agency, that a chilly prickle crept up and down my spine in spite of all sense or reason. Although perhaps not . . . I’m not nearly so sure now as I would once have been that reality is something one can always be so positive about. But that was later, and now, sitting there perfectly motionless, watching that slowly opening door, I saw, so dimly that it really did disturb me, a trembling black claw pressed against the dark cypress panel, and heard a dull thump-thump.

A tiny bent creature, as black as ebony, with a clean white kerchief around her head, crept out into the hall. She had a flat reed basket, the kind they send camellias in, in one hand and in the other a knotty stick to steady her crumbling joints. She didn’t see me sitting there in the dim half-light. She tottered slowly across the hall and stopped, supporting herself against the carved frame of the door nearest the entrance. I waited, a sharp almost breathless excitement constricting my throat. I hadn’t realized till then how over-poweringly stimulated my even normally pretty offensive amount of curiosity had been by Phyllis Lattimer and Mrs. Atwell Reid and Jennifer . . . and by the three pieces of old furniture there in the hall.

The old Negress moved her stick to the hand that held the basket, fumbled about in the folds of her skirt, and brought out a key. She put it in the lock and turned it, and turned the small polished brass knob. Then she switched the stick back to her right hand and pushed the door open.

I half rose from my seat, stopped and sat down again, not abruptly but very slowly.

Then I knew. But I’d known it already. It had nagged at the back of my mind the instant I’d walked across the threshold of Strawberry Hill, and again when Jennifer had crossed the hall to go up the stairs. Still I stared through the handsome carved door frame, with its broken pediment and carved little urn of strawberry leaves and blossoms and flowers, to the fireplace beyond. And I knew the secret of Strawberry Hill. I knew why Jennifer Reid had so desperately resisted my coming . . . and why the doors and windows were bolted and shuttered.

Strawberry Hill was empty. There was no furniture in it. No Chippendale settee with a ribband back, and except for the one, no ribband-back chairs to match. There wasn’t even a mantel behind that door, or a cornice, or any of the old carved panelling. Even the woodwork was gone; and the walls and chimney breast were bare and maimed and covered with black cobwebs where the panelling, the cornice, and the mantel had been ripped out—ripped out and sold. There was nothing beyond those doors—nothing but a pile of Irish potatoes on an old cracker sack in the middle of the cypress floor. I sat perfectly still, a sick and dreadful feeling in the pit of my stomach.

The old colored woman bent painfully down and started putting potatoes in her basket tray. I kept thinking, over and over, Jennifer didn’t want me to come, and this is why . . . but her mother did want me to come—and why did she? The first was clear. The second was not only not clear; it was profoundly disturbing. Did she know . . . or did she only guess?

Then suddenly I heard Jennifer’s quick step sounding and echoing in the empty house. The girl who was saving the treasures of Strawberry Hill for herself was coming back.