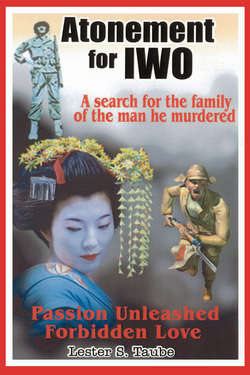

Читать книгу Atonement for Iwo - Lester S. Taube - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

In the morning, Masters made his way slowly down the three flights of stairs to the basement and unlocked the small, storage room provided for each tenant of the old, apartment house. Inside were two battered footlockers, a dust covered Valapack, and a Samsonite suitcase. He sat on a footlocker for a few minutes to rest, then kneeled and opened one. Among the folders of army orders, certificates, Veterans Administration letters regarding his pension for wounds, and personal papers, he found the wallet and the thousand stitch belt.

Back in his one roomed apartment, he opened the wallet. It was mildewed, cracked, and heavy with the odor of the sands, cliffs and volcano ash. The small amount of Japanese money was gone. Bert had swiped it when he was six or seven years old to show round the neighborhood. It had then disappeared casually, as if it had been placed in a clothes drawer and had fallen to the floor while the clothing was taken out, then carelessly laid on top of the bureau to be swept up during a periodic housecleaning.

Directly in the center of the wallet and its contents was a jagged hole, bored out by one of his submachine bullets on its way through the pocket of the Japanese sergeant’s shirt before thundering into his chest. Master lifted the leather flap and took out a picture and a small, white name card.

The picture and the card were stuck together. He sat in a chair next to the single lamp in the room and peered closely at the photo. It was of a short, slim man of twenty two or so, seated on a bench in a photo studio and wearing a khaki uniform and visored cap. Master strained to see if he had stripes of rank on his collar or sleeves, but the picture was too distorted by the passage of time. On his lap was a child. It would have to be a boy, for he wore a little visored cap similar to that of the soldier. The features of the man and child were blurred. He tried to guess the boy’s age. Perhaps six months old.

Standing slightly behind and to one side of the soldier was his wife, a slender woman, straight as a reed, dressed in a kimono, her hair piled high on her head and perfectly arranged. He could not see her face, for the bullet had torn squarely through it. In her left arm she held another child, about two years old, who was likewise dressed in a kimono with an obi peeking out from the side. The girl’s face was the clearest. It was long, serious, containing large, expressive eyes and a pixie type snub nose.

Masters sat fascinated by the picture, putting it down with great reluctance at noon to eat a frugal lunch and to take a nap. When he awoke, he continued studying it until suppertime, then, when he had eaten; he put on a pot of water to boil and held the photo and card over the steam. Patiently, he moved his hand to and fro until he had them unstuck, giving a sigh of relief to see them come apart without damage.

The name card bore a line of Japanese characters running from top to bottom. The bullet had entered a bit off center and touched one of the characters, but they were all readily identifiable.

He placed the card and photo on the lamp stand to dry, then switched on the television. Frequently, during the evening, he turned off the television set and picked them up, staring as intently as before.

The following morning, he bundled up warmly and descended the staircase to a store at a corner. There he looked up a telephone number, then entered a booth and dialed.

A woman’s voice answered. “Berlitz Language School, good morning.”

“Do you have courses in Japanese?” asked Masters.

“Of course, sir. Three times weekly, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, at seven p.m.”

He hesitated. “How much are they?”

“One moment, please.” A short time later she was back. “In a group course, it is seventy-two dollars for twelve weeks.”

“Thank you.”

That evening, Masters registered at the school, disappointed to learn that new classes would not begin until after the first of the year.

“Could I speak with the instructor for a few minutes, please?” he asked the registration clerk.

The clerk glanced at her watch. “I don’t think he’s started his classes yet.” She directed him to the proper room.

The instructor was a stout, middle aged Japanese. Masters handed him the card.

“Could you please tell me what is written here?”

“It’s a name. Ito Tanaka.”

“Does it have any meaning?”

The Japanese shook his head. “No, it’s just a name. Quite often a woman carries a name with a meaning, such as a flower or an incident, but it’s rare for a man. It’s a common name, though, this Ito Tanaka. Probably a farmer or a villager.”

Masters walked home slowly, muttering, “Ito Tanaka. Ito Tanaka.”

The next morning, he made his way to his former insurance office. George Brighton was in his office checking over delinquent accounts.

“For Pete’s sake, Keith,” he said, getting up to help Masters doff his overcoat. He placed it on a rack near the door. “What are you doing out in this weather? Don’t you know it’s freezing outside?”

Masters took the seat offered by Brighton and smiled. “Of all the things I’m not afraid of, it’s catching cold. George, I want to borrow on my policies.”

“All right, Keith.” He rang for a clerk and told her to fill out the forms. “Do you want the money right away?”

“No, let it come through normally.” He hesitated. “I’m going to Japan this summer.”

“Japan! Are you out of your mind?”

Masters leaned over the desk. “George, you’re one of the most understanding people I know.” He gnawed gently at his lip for a few moments, concentrating on how he should express himself. “A couple of nights ago, right after you left, I started thinking about myself. I guess when you’ve faced death as closely as I did last summer, you begin to ask yourself some questions.”

Brighton interrupted. “You’ve faced death long before last summer. What about the War, and Korea?”

“That’s different. I was a husky kid then. In battle you know one thing if you don’t get the big one that day, you’re still young and healthy and can fight like a son of a bitch the next day. Since last summer, I learned that I can’t fight anymore. All I can do is delay the big one.”

“Okay, Keith. You’ve got something on your mind. Let’s have it.”

Masters sighed and chewed his lip harder. “A couple of nights ago I realized that I had murdered a man.”

Brighton eyes opened wide in surprise for the merest moment, then he got up, strode to the far end of the office and shut the door, which was slightly ajar. He took his seat, his expression guarded. “Keith,” he said softly. “Do you know what you’re saying?”

Masters raised his hand. “Relax, George. The killing was considered legal. In fact, they gave medals for it.”

Relief spread over Brighton’s face. “You mean war, don’t you?”

“Yes. I was responsible for the murder of a man.” The manager sat quietly, eyeing him. “I allowed one of my sergeants to shoot this Jap. I could have stopped it, but I didn’t. I guess I’ve always known I was responsible for his death, but I was unable to admit it to myself until a couple of nights ago.”

“Was he a soldier this Japanese?”

“Yes.”

“Was he armed?”

“Yes.”

“Had he surrendered?”

“No, but he was severely wounded. He wasn’t able to fight anymore.”

“Did you order this sergeant to shoot him?”

“No.” Masters paused, then sighed. “But I wanted him to.”

Brighton leaned back, lit a cigarette while he digested what Masters had said, then blew smoke towards the ceiling. “Keith, I was with the Judge Advocate during the war. Your case occurred so many times that you couldn’t count them. There isn’t a court in the world which would find against you or your sergeant. You are in the midst of a firefight and you put a bullet into an enemy. An enemy, Keith. Get that word fixed in your mind. The enemy is sworn to kill you, any way he can. Anyhow, after you put a bullet into this...enemy, you take out insurance by putting another bullet into him. Whether he’s kicking or not, you shoot him good. I think that’s being a smart soldier, not a murderer.”

“And if he had surrendered?”

“That’s different.”

“And you conclude that a wounded man, unable to lift a finger, is not the same? Maybe he wanted to surrender, but didn’t have the strength or time to turn his head and say so.”

“That’s known as real tough titty, Keith, and if you’ve heard one bullet fly by your head, you know it’s the truth.” Brighton hesitated. “Look, I’m not a psychoanalyst, and you’re not the kind of person who needs to be told that your heart attack has released all sorts of fantasies. I assume that you firmly believe what you are saying, and that it had lain dormant how long?”

“Twenty years.”

“Okay, twenty years. Furthermore, because it happened twenty years ago doesn’t mitigate it nor make it any the less important. I also see that even though you didn’t pull the trigger yourself, you feel a moral guilt. But moral guilt, or even actual guilt, is something we all have inside us in some form or another, and we have to live with it. Look at Hank Wasinski. Every time he lays with his wife and uses a rubber he believes he is committing a mortal sin. It preys on his mind, but it must be lived with.”

“But he hasn’t murdered.”

“That’s not the way Hank sees it. But let’s get one point straight right now. You haven’t murdered anyone. I don’t speak of it in just a legal sense, because legally you have complied with all the rules of warfare, even though your enemy, and again, I repeat, your enemy, did not believe in nor abide by the Geneva Convention Rules of Warfare. Morally, you had two alternatives, to fight for his life, if you felt disposed to, or to take it, and taking it was the result of every bit of training you ever had in the army.” Brighton shook his head. “Keith, you cannot castigate yourself for this incident.”

Masters sat quietly, reflecting. “Thanks, George, you’ve explained yourself well and I understand what you have said. But I still think differently, and I am not trying to build up a case because I have nothing better to do or to make a mountain out of a molehill. Look.” He leaned forward again, trying desperately to explain himself. “You find a man lying on the ground, bleeding from a wound which requires only a slight pressure on the artery to stop it. He can be a complete stranger, or a guy whose guts you hate. You walk away and let him bleed to death. Are you guilty?”

Brighton met Masters’ eyes levelly. “You are not guilty of murder,” he said softly. Under Masters continuing stare, he finally looked down at his desk. There was a long silence. “What do you expect to accomplish in Japan, Keith?” he asked.

“I don’t know, George, I don’t know. Maybe seek atonement for my sin. I must do something besides sit here and think of it.” He rose and held out his hand. “So long, George.”

Brighton stood up. “Do what you must, Keith. But keep in touch.”

The old, battered cargo ship came alongside the dock in Yokohama. Masters stood at the rail to watch the Japanese stevedores, garbed in cotton shorts and sleeveless shirts, with red sweat bands on their foreheads, swarm along the piers loading and unloading ships. The brisk, salt tanged air caught up the scent of fish and frying oils mingled with the harsh odors of radish and peppers and cabbage. The small, heavily muscled workers were an orderly mass, wheeling forklifts and swinging cranes.

The July weather was bright, invigorating, and the slow trip across the Pacific had worked wonders for the lonely man with the defective heart.

His eyes turned to the southeast, to the Hommoku misaki, the promontory known as Treaty Point. For a moment his thoughts went back to his rest leave from Korea and to the Japanese girl whose name he could never pronounce, whom he had nicknamed ‘Betty Grable’. She had taken him sightseeing at the promontory, and had said, “Here’s where it all started, the flow of foreigners which has never stopped.” They had sat there looking out over the bay, then had decided that going back to their hotel in Tokyo would take too much time, so they had rushed to one nearby to do what Masters had come to Japan to do.

He glanced towards the north, unable to see but sensing the movement of the unbelievably crowded Tokyo, remembering the long strolls through the teeming streets where he felt like a giant among the short, slim, beautiful Orientals.

His clearance through immigration and customs took but a few minutes, and he was amused at the results obtained by speaking his limited Japanese, for there was always a bow and a smile. The three months at the Berlitz school were not completely wasted.

He was directed to a bus and sat next to a heavy browed Japanese, who kept his eyes glued to a newspaper while the vehicle raced recklessly through the narrow streets of Yokohama and into the maelstrom of the Shitamachi, or downtown Tokyo. Masters had to agree that adverting one’s eyes, was the only defense against the terror of driving in Tokyo.

He found a small, inexpensive hotel near the terminal. The room was just wide enough to stretch his arms, but it was clean and orderly. It did not have a bathroom. The community toilet and bath were down the hallway.

His first call was at the American Embassy, where he learned that the agency which handled veterans’ matters was the Gunjin Kazoku Enjo Kyokai, The Association for the Protection of Families of Soldiers. As it was now too late to visit, he walked the streets to see the changes which fourteen years had wrought. It was like being in Chicago or New York or Philadelphia if one could read the Japanese characters over the stores.

He stopped abruptly at the first pachinko stand, a sparkle coming to his eyes as he brought twenty five small, steel balls, and put them one by one into the machine, pulling the trigger and watching them shoot up, then work their way downward through the scores of nails to the various slots at the bottom. He hit the winning slots a number of times, took a handful of the balls back to the counter, and received three bars of candy in exchange.

He strolled by the Emperor’s Palace, stopping to watch the fat, golden carp swim lazily in the moat and wonder how many generations of fish had come and gone since he had last gazed into the same moat. In a simple restaurant in the Ginza section, he ordered boiled fish and vegetables which he had seen served to another customer. He pointed it out to the waitress, for he did not know how to ask for it in Japanese.

The next morning, he found the Association for Protection of the Families of Soldiers, and was taken in tow by a middle aged man who spoke English.

“Ito Tanaka? Iwo Jima? Please wait here.” In half an hour, he returned with a dossier. “Yes, we have him. He was a sergeant in an engineer battalion at Iwo Jima.” He pronounced battalion as “battarian”, since most Japanese were unable to use the letter ‘l’. His face saddened. “We have absolutely no information as to what happened to most of the twenty two thousand people on the island. With the exception of a handful who surrendered, we have listed all others as having been killed in action.”

“We had several thousand casualties, too,” said Masters, remembering quite clearly saying goodbye at the graves of many of his men and fellow officers before leaving the island.

It caught the man short. “Yes, of course,” he mumbled.

“Tanaka’s family? What about them?”

The man scanned the dossier again. “As of nineteen fifty, his wife and two children were residing near Akimo, a small village about one hundred and twenty miles northwest of here. That was sixteen years ago. I would assume that they are still there.”

“Why would you assume that?”

“The Nipponese peasant remains with the land, especially a widow with two small children.”

“How can I find out for certain?”

“The National Police would be able to assist you.”

The National Police were indeed helpful. Within minutes, a sergeant, eyeing Masters curiously, wrote out a name and address on a slip of paper.

“Mrs. Tanaka now resides in Tokyo,” he said. “Is it possible to explain why you are looking for her?”

“It’s a personal matter.” Masters observed a gleam of amusement flicker across the sergeant’s eyes. “Does something amuse you, buster?” he growled.

The gleam instantly disappeared. “Of course not,” he replied politely, handing over the slip of paper. On it was written, ‘Kimiko Tanaka’ and an address.

Outside the police headquarters, Masters flagged down a cab and showed the slip of paper to the driver. “Yamanote,” said the driver as Masters stepped inside, and promptly took off with a breathtaking dash of speed.

Masters found the word in his information book with an explanation that it was the finest residential section of Tokyo.

The taxi drove west into the suburbs and drew up in front of a large, magnificently designed one story house of polished, white stone, its roof of glistening red tiles rising at the eaves in a classical Japanese arch. A fastidiously tended garden surrounded the house, and was in turn enclosed by a high, bamboo fence. Masters looked with dismay at the driver.

“Is this the right house?” he asked.

The driver nodded. “Yes, Mister. Same address as on paper.”

“You’d better wait.” He climbed out, opened the gate, walked up the flag stone pathway to the front door and knocked. A small, wizened woman came to the door. “Mrs. Tanaka?” he asked.

The old woman, a number of teeth missing, bowed and answered.

“What?” asked Masters, not understanding her.

She spoke again.

Masters shook his head. “Is Mrs. Tanaka here?” he asked once more.

The taxi driver, observing the situation, came up and talked to the woman. He turned to Masters. “Mrs. Tanaka,” he explained, “lives here. Not home before seven o’clock tonight. Works at store downtown.”

“Can you get the address of the store?”

The driver spoke briefly to the servant. “Have address. You want to go there?”

“Yes.”

The driver turned his vehicle and drove to the Ginza sector of downtown Tokyo, where he drew up in front of a large, fashionable shop. Masters paid him off, then glanced through the windows as he slowly strolled by. It was an exclusive women’s boutique, selling lingerie, dresses, sweaters and night wear. Six or seven smartly dressed saleswomen were waiting on customers. Masters walked on a couple of blocks, took a coffee, then returned. It was still busy inside. His eyes passed over the women inside, hoping to pick out the one he was seeking. Two of them were about her age.

He waited for a lull in the business, then entered. A young woman came up at once. “May I help you, please?” she asked in Japanese.

“I am looking for Mrs. Tanaka.”

“One moment, please.” The salesgirl knocked at a door at the rear of the store and went inside. A short while later, a woman came out.

Masters studied her closely as she approached. She was a small woman, about five feet tall, slender, with black hair drawn tight into a bun at the back of her head in the old fashioned manner. He saw immediately that she had had eye operations to reduce the slant, and that her cheeks and lips were slightly touched by cosmetics.

She was an elegant woman, typically Japanese, well formed, erect, walking with a graceful air. He guessed her age to be forty.

“I am Mrs. Tanaka,” she said, keeping her eyes from looking directly at him, another old custom.

“My name is Keith Masters,” he started in Japanese.

“Would you prefer to speak English?” she asked, with only a faint accent.

“Yes, very much so,” he replied, relieved. He glanced round. “Could we speak privately?”

“Of course. Please.” She led the way to the office in the rear. It was tastefully furnished, a polished walnut desk, two slim straight-backed chairs, a cushioned sofa, and thick wall to wall carpeting. Fresh flowers were on the desk, carefully arranged in a hand painted vase. She motioned courteously for him to be seated while she remained standing.

He drew in a deep breath as he reached into an inner pocket of his jacket. “Do you recognize this?” he asked, handing her the photo.

She took it with a bow of her head and glanced at it. Suddenly, her eyes widened and her lips parted. The color flew from her face. A slender hand darted to her mouth to stifle the cry welling up. Her black, intense eyes flashed towards Masters, eyes filled with a groping hope mingled with the terror of final judgment.

“Where is he?” she finally whispered hoarsely.

“He is dead,” said Master bluntly. “Sit down, Mrs. Tanaka.” Her eyes had closed and her hands had covered her face. She stood rigid, silently weeping, then began to rock with grief. “Do you want some water?” he asked. She shook her head.

He rose and walked to the window behind the desk. It faced a cobblestone alley where half a dozen boys were playing baseball with a small wooden bat and a rubber ball. He deliberately looked away until she regained her composure.

“Where did you get the picture? How do you know that my husband is dead?” The two questions were whispers.

He turned. “I was on Iwo Jima. One of my men took it from the body of a Japanese sergeant. He gave it to me.”

She was fighting desperately for control. “Was it definitely my husband?”

He nodded. “It was him. I will go now.” He started towards the door.

She trembled as if he had struck her. “Please, please, do not go. There is so much I want to ask.”

He stopped. “All right.” Picking up a pencil from the desk, he wrote his name and hotel on a pad. “I am staying here. I will not leave until we speak again.”

She gave a sigh of relief. “Please, Mr. Masters.” She glanced quickly at her watch. “I will be leaving in an hour. Would you visit my home this evening, for dinner?”

“I’ll come over afterwards. Eight o’clock.”

“Do you know the address?”

“Yes. I was there earlier this afternoon. An old woman gave me the address of this store.”

As he started from the room, Kimiko whispered pleadingly. “Please come, Mr. Masters.”

He halted. “I’ll be there.” Then he went out.

At exactly eight o’clock, the taxi drew up in front of the house. Kimiko was waiting at the door, as if she had been standing there since the moment of her return. Her eyes lighted up with relief.

“Good evening, Mr. Masters,” she greeted him with a bow. “Thank you for coming.” She led him into the living room. It was unusually large, its walls covered by delicately colored silk cloth. Two Italian provincial sofas, matching armchairs, and hand carved, straight-backed Louis XIV chairs of oiled cherry wood were tastefully located. To one side stood a combination television stereo set. He was surprised, for it was totally European. So unlike his opinion of her being traditionally Japanese.

A young, stunningly beautiful girl, wearing a sheath like dress, was seated on one of the straight backed chairs. She stood up as they entered.

She would be about twenty three or four, reasoned Masters.

“This is my daughter, Hiroko,” said Kimiko.

The girl was taller and more rounded than her mother. They shook hands in the western fashion. “Good evening, Mr. Masters,” she said easily, although it was evident that she had heard of him and knew the reason for his visit.

“Would you care for something to drink?” asked Kimiko. He could see from her deep breathing that she was controlling her nervousness only by a great effort.

“I cannot drink whisky,” he replied. “May I have tea?”

“Of course. I would be most pleased.” She walked quickly to the kitchen to give instructions.

Masters took a seat on the sofa across from the girl. He could hardly keep his eyes from her. The long, narrow face in the picture was still the same, the skin a flawless ivory, subtly rouged, and the almond shaped eyes which filled her face held the same soft, black irises of her mother. Her hair was piled high on her head, held in place by a band of sparkling rhinestones.

“Mother said you know of my father.” She spoke English fluently, with the merest hint of a lisp.

“Yes. I wish it could have been happy news. I’m sorry.”

“You must not be. We have always been certain that he...” her voice lowered, “...was dead. But there was still the constant shred of doubt which lingered in my mother’s mind and it caused her considerable sadness. Now, at least, she will be able to accept the finality of his death.” She leaned forward. “Please, Mr. Masters, my mother is from the old Japanese way of life. It will be very difficult for her to ask you to speak. This is because of our custom between man and woman. Please help her.”

Hiroko broke off the conversation as Kimiko led in the wrinkled servant carrying a tray. When they were served, Kimiko sat on a stiff backed chair and folded her hands. Her eyes fastened on Masters.

“Please, Mr. Masters, would you tell us all you know about my husband.”

Masters sipped the fragrant drink slowly to collect his thoughts. “I was a platoon leader on Iwo Jima,” he said slowly. “We were mopping up in the hill area at the north end of the island. A group of our men had a fight with four Japanese soldiers in a cave along the beach and killed them. A wallet and a thousand stitch belt was taken from your husband.”

“Did you see him?” whispered Kimiko.

“Yes.”

“How did he die?” she whispered again, brokenly. Her jaw muscles were tight and the skin of her hands shone white with the pressure upon them.

“He died instantly. Without pain. He died fighting as a soldier.”

A small sigh escaped from Kimiko’s lips. “Thank you with all my heart, Mr. Masters, for having come to tell us.” She was struggling to control the tears. “Do you know where I can find the body?”

They had left the corpses to the sun and the sea crabs. Perhaps burial patrols had found them later to fling the remains into the common burial pit with the thousands of other enemy soldiers.

“He was taken to the main Japanese cemetery and interred with his comrades. There were no means by which our forces could keep individual records, so they were buried together.”

“Who killed my father?”

Masters’ head lifted at the sharp question from Hiroko. Her eyes were flashing.

“Hiroko”“ called Kimiko, appalled that a guest, especially a man, should be spoken to in such a manner.

“That’s all right, Mrs. Tanaka, she’s entitled to know.” He turned back to the beautiful girl and looked at her levelly. “There were many soldiers shooting at the same time, not only at your father but also at his three comrades. It would be impossible to say which one actually killed him.”

“Did you shoot also?” she asked bluntly.

A dark silence fell over the room. Masters slowly placed the teacup and saucer on the table by his side and stood up.

“Yes. I shot, too,” he replied quietly.

In the utter stillness, he strode to the door and let himself out, then walked slowly down the street until he found a passing taxi that took him to his hotel.

Back in his small room, he lay fully dressed on the bed, listening to the pounding of the tired organ he called a heart, feeling no release of relief, no sense of expiation, only a heaviness and inertia. When dawn began to steal through the single window of his room, he finally fell into a fitful slumber.