Читать книгу Between Christ and Caliph - Lev E. Weitz - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Marriage and the Family Between Religion and Empire in Late Antiquity

A man from Babta betrothed a woman to his son in the customary manner.

When the day of the wedding banquet approached, he went to the holy one and convinced our Rabban to pray over them lovingly.

The blessed old man said to him, “Hear what I have to say to you.

See when you go to the Euphrates to bring the bride to your son that no singers inviting destruction go with you on your way.

Instead, gather joyfully priests and chaste Levites.

Go and come in service to the church, and Christ shall be with you.”

… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …

When [the man] went [home], his brothers and family would not listen to him, saying,

“We won’t spoil our pleasure, which will be celebrated according to our custom.”

But when they arrived halfway on their way

a demonic vision appeared at once to the bride.

—History of Rabban Bar ʿEdta (d. c. 611)

In the mid-seventh century, an East Syrian monk composed a laudatory biography in Syriac of Rabban Bar ʿEdta, his spiritual master and a Christian holy man who spent his life in the Christian plains and hill country of Sasanian-ruled northern Mesopotamia.1 Among Bar ʿEdta’s many spiritual exploits was the episode recounted above, in which a man from the village of Babta sought the holy man’s blessing for his son’s impending marriage. Bar ʿEdta agreed, as long as the ceremony was to be conducted in an appropriately chaste and pious manner. Here, however, “custom” (ʿyādā) got in the way; the groom’s uncles insisted on having whatever celebratory music the people of Babta were used to hearing at their parties, and no holy man was going to ruin this one. What did these “singers inviting destruction” (zammārē mawbdānē) sound like? Were the rhythms or lyrics of their songs too suggestive for the holy man’s liking? The author gives us no details, but apparently the Babta singers made literal devil’s music—their voices attracted a troop of evil demons (plaggtā d-shēdē bishē) that, among other things, caused the bride to strip off her clothes as she rode a donkey to the wedding. Only with some holy oil from Bar ʿEdta, and by replacing the singers with psalm-chanting priests and deacons, was the bride’s procession able to fend off the demons, get back on track, and make it to the church on time.

This passage encapsulates tensions between the requisites of Christian belonging, on the one hand, and practices associated with the institution of marriage, on the other, in the empires of the late antique Middle East, tensions that it is this chapter’s goal to explore. In the societies of late antiquity on both sides of the Roman-Sasanian frontier, marriage had long been understood as a foundation stone of social and political organization. It was the institution that legitimized sex so as to reproduce humans not only as a species but as social beings organized in specific household, lineal, and political forms. At the same time, the theological import of human sexuality to Christian tradition made marriage a locus of debate and reform in the eyes of bishops and other Christian thinkers. Christian thought and ecclesiastical regulation called for sweeping changes to its practice, enjoining monogamy, restricting divorce, and emphasizing chaste avoidance of sexual overindulgence (hence Rabban Bar ʿEdta’s opposition to the singers of Babta). Yet older marital practices did not simply disappear. Imperial, civil, and local legal traditions continued to set the norms by which marriage as a legal relationship was enacted, governed, and dissolved, and these were often at odds with Christian prescriptions. Ecclesiastical law in both the Roman and Sasanian empires never usurped that constitutive authority; rather, it encouraged pious modifications to an ancient social institution, and many of the associated elements it condemned lingered on in practice. Thus could the people of Babta seek simultaneously a Christian holy man’s blessing and transgressive entertainment at a wedding. These tensions at the nexus of marriage, law, and religious belonging in the late antique world form, in turn, the backdrop to developments in later centuries, when Christian bishops’ encounter with Islamic empire spurred them to bring marriage and the household wholly under the authority of ecclesiastical law.

MARRIAGE AND SEXUALITY IN THE LATE ANTIQUE IMAGINATION AND CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY

Although demonic interference was no doubt a singular and unexpected event, when the bride and groom from Babta went down to the waters of the Euphrates to marry, they were partaking in a wholly ancient institution that had been enacted untold numbers of times in the thousands of years of the Middle East’s recorded history. The challenges of various ascetic movements notwithstanding, an average observer of the societies of the late antique Roman and Sasanian empires could have taken marriage largely for granted as a common social institution—that is, as a collection of recognized “ways of doing things” that structured particular human actions and relationships, and which “provide[d] stability and meaning to social life.”2 Anthropologists maintain that while marriage is nearly ubiquitous in human societies, any universal, cross-cultural definition will be inadequate.3 Essentially all late antique eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern societies, however, shared a general sense of what marriage was and what it did. It was the enduring crux of biological and social reproduction; it enabled the formation of the other institutions that were the building blocks of social and political organization, the family and the household.4 Marriage rendered sex between a man and a woman licit and any resulting progeny legitimate (though some other institutions that were not marriage in strict terms could do the same). It established new ties between previously unrelated individuals and kin groups. By affiliating progeny to families and lineages, furthermore, marriage outlined the paths by which both material property and genealogical cultural capital—the status associated with ancestry—would devolve to new generations. Marriage, in other words, was the chief institution that facilitated the reproduction of both the human race biologically and the hierarchies of lived human societies, generation after generation.5

The peoples of the ancient Middle East were well aware of this fundamental connection between marriage and the broader associations to which humans belonged, and so they often assigned the institution particular cultural weight. Augustus, the first Roman emperor, enacted legislation promoting marriage and childbearing among Roman citizens for the good of the empire.6 In Zoroastrian cosmology, marriage with particular kin relations was a pious act that modeled the “divine and mythical unions” of the good god Ohrmazd with his daughter and mother.7 For early rabbinic Judaism, distinctive marital customs signaled the continuity of “one Israel” stretching deep into the biblical past.8 In a similar vein, marriage, as the legitimate channel of human sexuality, became an important locus in the development of Christian thought, which from its earliest days recognized a fundamental connection between sexuality and humans’ potential to achieve salvation. Characteristically Christian understandings of that connection, however, departed radically from most Greco-Roman, Zoroastrian, and Jewish traditions (not to mention later Islamic ones). Most ancient marital regimes and systems of sexual morality were organized around the reproductive imperative and placed great value on it. Essentially all Christian traditions, on the other hand, came to see abstention from sex as the highest, most pious mode of living in the material world in anticipation of perfection in the next one. The very utility of marriage and its reproductive purposes was uncertain at the least and wholly superfluous when this logic was followed to its extreme. A theology and ethics of sexuality rooted in the valorization of continence thus became an integral piece of Christian thought in the late antique and medieval Mediterranean world.9 It persisted in marked tension, however, with the practice and regulation of marriage as a social institution in the imperial legal orders of late antiquity.

Map 1. The Middle East in Late Antiquity

The notion that membership among the Christian faithful required chaste sexual practice was rooted ultimately in the teachings of Paul’s epistles, most famously in I Corinthians 7. Paul’s letter gives a “passing endorsement of continence as an optimal state,” which, while not providing a systematic theology of sexual renunciation, set the parameters of later Christian thought on the subject.10 Early Christian thinkers of later generations outlined a soteriological vision that valued virginity and continence—the eschewal of human sexuality altogether—as the most perfect way of life in an imperfect world and the surest path to salvation in the next. The institutions through which early Christians put these ideas into practice were highly varied and contested. More radical groups called Encratites by their opponents required celibacy of all the faithful; in northern Syria and Mesopotamia, lay celibates known as Sons and Daughters of the Covenant lived among their householder neighbors; cenobitic monasticism, celibates living in communities separate from lay believers, developed especially in Egypt before spreading elsewhere.11 By the fifth century, a rough pattern had begun to emerge that increasingly cordoned off sexual renunciation as the proper vocation of monks and high ecclesiastics.12 But virginity and continence retained their supreme rank on the scale of chaste sexual practice in the Christian imagination.

If sexual renunciation was of such value, however, where did that leave the vast majority of Christians—ordinary householders who had sex and had children, and without whom the church in society would no longer exist? Virginity and continence had theological weight; they were perfection in imitation of Christ and the angels, which sexually active lay marriage was not. Yet scripture carved out at least some place for the latter in Christian cosmology. Genesis 1:28 commanded humans to be fruitful and multiply. Ephesians 5:23 compared marriage to Christ’s relationship with the faithful—“the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ is the head of the church.” As Christianity grew from a marginal movement to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire and beyond, it became all the more imperative for Christian thinkers to expand on these teachings and articulate conceptions of sexual practice within marriage that, if not as perfect as continence, constituted at least an acceptable standard of chastity for everyday believers. In the late antique eastern Mediterranean, Christian teachings on chaste lay sexuality coalesced around three principles: the indissolubility of the marriage bond, the unlawfulness of sexual activity outside of monogamous marriage, and the procreative purpose of sex within marriage.13 The Church Fathers built these principles out of a range of received teachings. Especially foundational was the biblical notion that a man and woman become “one flesh” through sexual intercourse (Genesis 2:24). Christian thinkers understood this as a divinely decreed, essentially indissoluble ontological status—hence Jesus’ teaching against divorce, “what God has joined together, let no one separate” (Matthew 19:6, Mark 10:8–9). Equally significant was Paul’s insight that, given the divine institution of the singleness of flesh, any sex outside of a monogamous marital union was fornication (porneia), inherently defiled and defiling (1 Corinthians 7).14 Finally, strands of Stoic philosophy contributed to the early Christian imagination the conviction that if sex within marriage was lawful, it was so only for reproduction rather than for pleasure, wage labor, or any other purpose.15

These perspectives defined late antique Christianity’s theology of conjugal, chaste sexuality. In the centuries before Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, they were a radical departure from a Greco-Roman sexual culture in which divorce was relatively simple and extramarital sex with dishonorable bodies (slaves and prostitutes) had been perfectly acceptable for men. The circumscription of licit sexual activity to the single, indissoluble, procreative marital bond was thus a major innovation.16 It was also a practical one, in the sense that it provided householders who could not achieve perfection in virginity or continence a means to ensure their worthiness of salvation. The Greek and Latin Church Fathers (John Chrysostom and Augustine are two major exemplars) constructed this message in a substantial body of theological literature, much of it admonitory and for lay consumption. Little has been written on the theology of lay marriage in the early Syriac traditions of the Christian east, our main area of interest. In general, early Syriac writers like Aphrahat (fl. fourth century) and Ephrem (d. 373) contemplated the virtues of virginity extensively while devoting less attention to worldly marriage,17 although they invested great significance in an ecclesiology of marriage according to which the church looks forward to union with Christ the bridegroom in the world to come.18 When late antique churchmen of the Syriac traditions did consider the theological dimensions of marriage, they offered a formulation of chaste, procreative sexuality likely deriving from the synthesis of biblical, Stoic, and Aristotelian perspectives found in the writings of Clement of Alexandria (d. 215).19 In a nutshell, marriage for them was the divinely instituted, rational ordering of sexuality for procreative purposes that distinguished humans from non-rational animals. In Jacob of Serugh’s (d. 521) homily On Virginity, Fornication, and the Marriage of the Righteous, for example, sexuality outside the framework of procreative marriage is associated with subhuman, non-rational animals:

Anyone who remains in virginity is of the spiritual ones, and anyone who walks the path of the righteous [i.e., the married] is of the holy ones;

but anyone who descends to fornication is of the animals. Of the one [human] race there are three classes of people.

Among them are those who walk in virginity with the spiritual ones, in the path higher than worldly ways.

Others take the path of the righteous with marriage, the path pure of blame and censure.

Others descend to fornication, the wicked life, and resemble beasts and animals.20

Virginity is the highest degree of spiritual achievement to Jacob, but a rational sexuality within marriage, distinct from the random mating of animals, is still a mark of righteousness. The East Syrian patriarch Mar Aba (r. 540–52) gives a more definitive if less poetic expression of the same ideas. Mar Aba describes marriage as the institution “which God has established [sāmēh] for admirably administering the maintenance of our nature and the succession of our lineages [yubbālā d-sharbātan], not in the likeness of beast[s] lacking discernment [law ba-dmut bʿirā d-lā purshānā], but in an order that suits rational beings [b-ṭaksā d-ʿāhen la-mlilē].”21 Here we find the core elements—marriage as the ordered facilitator of the procreation of rational humans, as opposed to non-rational animals—of a characteristically late antique Christian conception of licit sexuality within the confines of the marital relationship.

LAW, MARRIAGE, AND RELIGION IN THE LATE ANTIQUE EMPIRES

The Roman Empire

The connection between sexuality and salvation spurred Christian thinkers in the empires of late antiquity to define the elements of Christian marriage—monogamy, indissolubility, and the restrained practice of sex. These ideas departed in several key respects from accepted norms in the Roman world, especially in their dramatic narrowing of the horizons of licit sexual practice. But in fact, Christian theology was only one of several normative orders that claimed the authority to govern the ancient institution of marriage and the domestic and familial relationships associated with it. These orders overlapped and interlinked in significant ways, but they remained distinct and Christian perspectives on sex and marriage never achieved absolute predominance within them. As a result, the reception of those perspectives by lay populations across the Roman Empire, as well as in Sasanian territory, was halting, uneven, and incomplete throughout late antiquity and into the medieval period.22

The most significant of the normative orders with which Christian thought interacted in this respect were the imperial and local traditions of civil law that governed the formation, maintenance, and dissolution of marriage as a legal institution.23 In the Roman Empire, this meant Roman law above all else, as well as its provincial iterations. An ancient and venerable imperial tradition, Roman law set the norms that governed relationships among persons, groups, and the state, in areas ranging from family law to property law to criminal law; it defined procedural rules for state organs; and it represented the will and authority of the emperor, his officials, and imperial institutions.24 In the area of the family, Roman law regulated the contracting of marriage, the transmission of property connected to it, and the other points at which citizens’ conjugal life intersected with the public arena.25 Indeed, Roman emperors had a long track record of legislative intervention in the affairs of Roman families and households (which, as elsewhere in the premodern world, were not necessarily coterminous because households often included slaves and other dependents in addition to biologically related family members). These legislative programs aimed to tie the citizenry to the imperium’s wider interests and ideological commitments. The trend began with Augustus at the turn of the millennium; it continued in Constantine’s highly novel legislation in the fourth century and, especially, Justinian’s massive legal codification project and Christian “moral activism” in the sixth.26 Significantly, however, Christian perspectives on sexuality were incorporated into Roman civil law only very partially, even as late antique emperors and jurists came to frame that law as divinely inspired and founded on Christian authority.27 Overall, Roman law continued to recognize as perfectly lawful many of the acts—chiefly divorce, remarriage, and men’s extramarital affairs with low-status women—that constituted unchaste, defiled sexuality in the Christian vision. Divorce is a particularly telling case. Constantine restricted the classical doctrine, which had allowed unilateral repudiation by either spouse without cause. His successors variously eased and reimposed restrictions; but all of this may have been motivated more by the need to regulate marital property exchanges than by Christian morals. Justinian, on the other hand, took the unprecedented step of prohibiting consensual divorce for two spouses who simply did not want to remain married, which was certainly a Christianizing reform in the context of his broader project of imperial regeneration. Yet this reform was so far outside the bounds of centuries’ worth of common practice that Justinian’s successor quickly rescinded the prohibition.28 Thus, across its tangled path of development and even in its partially restricted late antique form, the Roman legal doctrine of divorce never came close to the ecclesiastical ideal of indissolubility. From late antiquity into the medieval period, the Christian model of marriage continued to compete with old social mores encoded in or tacitly sanctioned by the civil legal structures of the Roman Empire.

Ecclesiastics had two principal tools to encourage laypeople to conform to their norms for conjugal conduct: “pastoral care and penitential discipline.”29 Persuasion and moral chastisement on the topic of sexuality became a central concern of late antique preaching for lay audiences, a trend perhaps best represented in the sermons of John Chrysostom (d. 407).30 More germane to our interests, penitential punishments for sexual transgressions were incorporated prominently into ecclesiastical or canon law, the legal tradition developed by Christian bishops to regulate matters particular to the church. From a very early date, Christian communities had been preserving treatises, pseudo-apostolic teachings, patristic epistles, and proceedings of church councils written in Latin, Greek, and Syriac that set down regulations for church affairs. By the fifth century, this body of texts had come to constitute a coherent legal tradition distinct from the law of the state.31 Representative works of ecclesiastical law range from early church orders like the Didache, a second-century text that regulated the duties of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and liturgical administration, to the proceedings of the Council of Nicaea and other ecumenical synods of the fourth and fifth centuries that defined orthodox dogma. While ecclesiastical law fundamentally concerned church affairs, it also included under its purview prescriptions of a broadly moral character directed to laypeople, particularly concerning sexuality. Lacking the same prerogatives of enforcement as imperial law, the ecclesiastical tradition usually sought to punish transgressors with exclusion from Christian rituals and communal participation. So, for example, the canonical letters of Basil of Caesarea (d. 378) prescribe exclusion from the Eucharist for fornication, among a number of other sexual offenses.32

Just as Christian moral teachings played a role in at least some of the later Roman emperors’ legislation, secular Roman law influenced the ecclesiastical tradition in significant ways. Justinian’s civil codification project was almost assuredly a major model of emulation for the ecclesiastical jurisprudents of the Greek east who began to produce newly systematized collections of canon law in the sixth century; in the late sixth or early seventh century, furthermore, canon lawyers incorporated pieces of Roman law relevant to church affairs into those collections, producing the joint ecclesiastical-civil legal compendia that scholars call nomocanons.33 But however much late antique Roman and ecclesiastical law overlapped, they ultimately claimed parallel jurisdictions with respect to the Roman family. When ecclesiastical law addressed itself to sexuality and marital practices, it extended into a civil area traditionally under the authority of Roman law; but only the latter retained the constitutive power to render marriage valid as a legal relationship (not to mention other civil contracts and transactions). To take another example from Basil’s canons, the Church Father could stipulate that the church would not recognize as marriage the union of a man and his third wife, but Roman law would still accord the relationship validity.34 Basil could exclude fornicators at the church’s door, but visiting prostitutes remained lawful in the eyes of the imperium.35 To promote properly Christian sexuality, late antique ecclesiastical law sought to modify behavior within an ancient institution that continued to be governed by and partly understood in terms of civil traditions.

The degree to which ancient attitudes toward marriage and the family persisted into the Christian empire is most evident in local legal practices as represented in documentary evidence—marriage agreements, divorce settlements, and related documents preserved in a number of Rome’s eastern provinces, especially Egypt. Marriage in ancient civil law traditions was always in some sense a contractual arrangement, in that it was a legal relationship created by an agreement between parties (usually the spouses and their families), but the law did not require the contract to be written in order for it to be valid.36 Those inhabitants of the eastern Roman world who did record their marriages and related transactions in documents, however, have left us evidence of strong continuities in the legal practices attendant to marriage and the formation of households throughout the era of Christianization; they demonstrate the conservatism of the Roman institution of marriage, which in practical terms changed slowly in response to Christian perspectives and even to new civil legislation.37 Divorce is perhaps the most emblematic civil practice of which orthodox Christianity disapproved but which clearly endures in the documentary record. Though they are not ubiquitous, a sizable number of deeds of divorce in Greek and Coptic, with provisions for the remarriage of the divorced spouses, are extant from Egypt from the sixth century into the eighth.38 So, for example, a no-fault divorce deed of 569 from Upper Egypt between one Mathias and his wife, Kyra, blames their separation on “an evil demon.”39 A sixth-century Greek document from the Palestinian village of Nessana records a divorce in which one Stephan retains the dowry of his former wife, who had either separated from him without cause or committed some transgression and thus forfeited her property to him.40 In a case that would have horrified any well-schooled bishop, an Egyptian fisherman named Shenetom divorced his wife, married another woman, and married his daughter to his new wife’s son—all on a single scrap of papyrus.41 Two other documents from Nessana evoke from a different angle the centrality of Roman civil tradition to marriage in the Christian empire. Both are marriage agreements, one dated 537 and the other 558, in which the groom acknowledges receipt of a dowry from the bride’s family “according to Roman custom.”42 Nessana was “an outlying village” on the edge of the desert in the province of Palaestina Tertia.43 Like elsewhere in the Roman world, Nessana’s Christian institutions, including churches, a monastery, and their officials, were central to local life.44 In a provincial setting like this in the heavily Christian later empire, the fact that these marriage contracts explicitly invoke the Roman example (whatever the actual content of their law) underscores how the legal-practical aspects of marriage and social reproduction remained intimately connected to notions of Roman citizenship, imperium, and law.

It is important to note that even though civil law retained constitutive authority over marriage as a legal relationship, ecclesiastics played important roles in its administration. It would take several centuries for the Latin and Greek churches to develop a systematic theology of marriage as a sacrament, but by the fifth century it was standard in the eastern empire for clerics to bless first marriages.45 Furthermore, many of the scribes and judicial figures who administered civil law, including that of marriage, were themselves Christian clerics. Constantine had granted official recognition to ecclesiastical courts in 318, and a career in the church was a path to status in the later empire.46 As such, the local notables who traditionally drew up deeds and contracts or witnessed documents might frequently hold clerical positions. To take one of numerous examples from the Egyptian papyri, a marriage contract of 610 from Panopolis (modern Akhmim) was witnessed by two priests, Moses and Yohannes.47 But while they certainly played judicial roles in administering marriage law, we should not assume that all Christian clerics were invested in enforcing the high tradition’s teachings on marriage and sexuality to the letter. In handling legal affairs they were carrying on a civil tradition that had always been a duty of prominent local men and officials; in the later empire Christianization had simply brought clerics to overlap with those categories. Indeed, the involvement of Christian figures in marriages did not necessarily imply the eschewal of practices lawful in civil terms but unchaste in ecclesiastical ones. Another Greek Nessana document, from the period of Umayyad rule but rooted in pre-Islamic Roman and local practices, is instructive here. The document, written in 689, records a divorce effected when Nonna, the wife, gives up her dowry and other marital property to John, her husband and a priest.48 Three of the seven witnesses are clerics associated with the local monastery of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, and the scribe is the priest and future abbot Sergius son of George. Though it may appear incongruous to encounter so many clerics affixing their signatures to a document attesting to a marriage’s dissolution (not to mention the crosses and invocations of God’s grace with which they embellished it), it is not necessarily so. These individuals were churchmen, but they were also custodians of the enduring civil traditions, rooted in Nessana’s recent Roman past, that governed the formation, maintenance, and dissolution of marriage.49 Christian tradition taught a radically new sexual morality, the Church Fathers and other ecclesiastics promoted it among their flocks, and some Roman emperors took it seriously when they promulgated new laws; but these developments never completely reformulated the Roman institution of marriage in the terms of Christian morality. Old and durable civil frameworks for contracting marital bonds and reproducing household life remained central to the understanding and practice of marriage in the later Roman world. The effort to create Christian marriage largely meant preaching Christian morals as chaste modifications to an ancient civil institution.

The Sasanian Empire

If imperial traditions defined the legal framework of marriage in the Roman Empire, how did the East Syrian Christian subjects of the Sasanian Empire relate to and interact with the judicial structures of a Zoroastrian polity? Which legal traditions had constitutive authority to render marriages legitimate? What role did ecclesiastical law play in the lives of East Syrians? These questions are more difficult to investigate than those concerning the Roman world due to a nearly complete lack of documentary evidence from Sasanian Mesopotamia and Iran and the fragmentary character of the extant Sasanian legal sources. Nonetheless, we can essay an educated outline. The available evidence indicates that Sasanian Christians, much like their coreligionists in the Roman Empire, followed a mix of imperial and local civil traditions to contract marriages. They did so under the purview, to varying degrees, of the Sasanian judicial apparatus. The Church of the East’s ecclesiastical law also did not differ greatly in its goals from canon law to the west: it encouraged suitably Christian forms of marriage, and ventured beyond the typical territory of Roman ecclesiastical law only in response to distinctively Iranian practices like close-kin marriage. Christian law did not have constitutive power over the formation of marriages; Sasanian Christians moved within a legal sphere defined by the empire’s official traditions.

The judicial institutions of the Sasanian Empire included a hierarchical array of courts staffed by a range of officials, many of whom were Zoroastrian religious professionals.50 The empire’s avowed Zoroastrianism, however, did not preclude the access to its courts of subjects of other religions; Christians, Jews, and other non-Zoroastrians were ineligible only for specific services closely connected to Zoroastrian ritual and doctrine.51 If Sasanian courts were open to Christians, however, did they actually make use of them? If nothing else, the question is worth asking because of the close connection between Zoroastrian doctrine and Sasanian judicial practice, and because we know East Syrian ecclesiastics to have maintained some form of their own communal judicial institutions, as did rabbinic Jews.52 Several factors, however, militate against the possibility that these resources constituted a completely autonomous system of law that obviated any need for Christians to make use of the imperial judiciary.53 Notably, Sasanian-era East Syrian bishops never claimed for themselves exclusive jurisdiction over the civil affairs of laypeople; they did so only for clerics. The bishops thus at least tacitly recognized the authority of Sasanian law and the imperial judiciary over all of the empire’s subjects, again like the rabbis.54 Christian judicial institutions, moreover, are likely to have been more informal audiences of ecclesiastics, monks, and lay notables rather than a centrally organized, hierarchical court system.55 Furthermore, the East Syrians’ ecclesiastical law never developed to cover the full range of civil affairs that would have been necessary had the bishops intended to fully insulate Christians from extracommunal law. Throughout the Sasanian period, East Syrian law was embodied in two main groups of texts: first, Syriac translations of foundational works of Roman ecclesiastical law—the canons of local and ecumenical synods, associated episcopal letters, and pseudo-apostolic writings—and second, the canons and proceedings of the Church of the East’s own synods.56 Like the received materials of Roman provenance, the East Syrians’ early synodal legislation dealt mainly with the organization of the ecclesiastical hierarchy rather than the civil affairs of laypeople (with a few important exceptions, discussed below). According to one recent analysis, this material demonstrates that East Syrian bishops never claimed the coercive powers of the Sasanian judiciary even when their law concerned civil transactions; they offered only spiritual punishments (essentially, exclusion from the Eucharist) for transgression. East Syrian law’s primary aim, rather than drawing laypeople into some discrete Christian legal sphere, was pastoral admonishment that not all the legal institutions available to Sasanian subjects were appropriate for true-believing Christians.57 In this respect, East Syrian law under the Sasanians was not unlike ecclesiastical law in the Roman Empire. Rather than providing a comprehensive legal system for Sasanian Christians, East Syrian ecclesiastical elites conceived of their legal tradition and their jurisdiction as complementary to other legal orders in the Sasanian Empire. We can be sure that many Christians sought the services of communal figures of authority to settle disputes. As subjects of the Sasanian King of Kings, however, they also certainly made use of state judicial institutions for at least some purposes.

The question of whether and how often they would have done so when they sought to contract marriages is more problematic. Sasanian bishops never claimed exclusive jurisdiction over the administration of marriage among Christians, nor did East Syrian law set any rules for how marriage was constituted as a legal relationship.58 The rabbinic tradition of the Mishnah and Talmud, by contrast, offered a thorough explanation of what made marriage marriage; in a rabbinic audience in the Sasanian Empire, a marriage was valid if it had been contracted according to rabbinic law.59 East Syrian law of the Sasanian period gave no such direction. At the same time, the family law administered by the empire’s courts was heavily structured by Zoroastrian cosmological principles—its “ideological foundation,” in the words of one scholar.60 A medieval Zoroastrian marriage contract that scholars believe to be based on Sasanian-era models, for example, is laden with Zoroastrian imagery and phraseology. It alludes to the liturgical recitation of “good utterances”; it calls marriage a “pious act” in the terms of Zoroastrian cosmology; and the bride states that she will not “deviate from … being an Iranian (ērīh) and (practising) the Good Religion (weh-dēnīh)” (i.e., Zoroastrianism).61 This model marriage contract is thus very much a Zoroastrian one. Did Zoroastrian scribes and judges only draw up marriage contracts like it? If they did, would Christians have made use of them?

One way or the other, it remains probable that Christians interacted with Sasanian judicial structures when dealing with legal business related to the family. The best reading of the evidence suggests that when the empire’s Christian subjects sought to record their marriages in written contracts, they would have had them drawn up by local scribes according to the conventions of either Sasanian law or local civil traditions. Subsequently, they would have had those documents confirmed by the seals of state officials or local notables, including ecclesiastics, making them eligible for adjudication by Sasanian courts. In this manner, even if Christians did not contract marriages according to Sasanian law, they still acted within a legal arena defined by imperial judicial practice.

In heavily Zoroastrian, Middle Persian–speaking regions of the empire that also had Christian populations, such as Khuzistan and Fars, it is reasonable to think that some Christians would, in fact, have gone to Zoroastrian scribes and judges to have marriage contracts drawn up according to Sasanian law. The writings of the East Syrian patriarch Mar Aba are instructive here. In the mid-sixth century, Mar Aba wrote a treatise and issued canons prohibiting Christians from practicing close-kin marriages, such as unions between a man and his father’s widow, his uncle’s widow, or his aunts. These practices were lawful and in some cases encouraged by Zoroastrian ethics and Sasanian law, but to Mar Aba they were fundamentally un-Christian.62 They were apparently common enough among Sasanian Christians, however, to warrant active condemnation. Notably, this indicates that the offenders (from Mar Aba’s perspective) were directly familiar with the substance of Sasanian family law, or at least with the distinctive marital practices it recognized and regulated. That such Christians would have contracted marriages before Zoroastrian judges or through Zoroastrian scribes is not at all unlikely. Perhaps they simply left the most overtly Zoroastrian language out of their contracts (or perhaps they did not).

For Christians in other regions of the empire, it is likely that local civil law traditions—what we might call common law—held sway. In these areas, Sasanian Christians would have turned to Christian scribes and notables, who often had positions in the church and/or the state and who were versed in local legal practices, to draw up marriage contracts. Generally, we might expect this to have been the case more in the heavily Christian areas of Mesopotamia than in the Iranian provinces of the empire. As we will see in Chapter 4, law books written by East Syrian bishops in the early ninth century prescribe forms of betrothal and marriage very similar to those of other regional legal cultures and to ancient, pre-Sasanian ones. Without overstating direct connections, this implies the continuity of regional common law traditions in Sasanian Mesopotamia, likely transmitted through scribal practice rather than encoded in normative treatises.63 When Sasanian Christians did not go to Zoroastrian judicial figures to contract marriages, we should imagine them doing so according to these regional legal traditions through the services of local Christian scribes.

Either way, Sasanian Christians would have been operating within the framework of Sasanian norms of judicial practice. The standard method of validating the content of a legal document in the Sasanian Empire was to attach to it a clay bulla impressed with the seals of office-holders and witnesses. If a document was sealed by a state official, a Sasanian court accepted it as fully valid. If a document carried only the seal impressions of private individuals as witnesses, it was up to the judge to determine its probative value.64 Presumably, any marriage agreement drawn up by a Zoroastrian judge would have received an authenticating seal impression. But even if non-Zoroastrian contracts were sealed only by witnesses, the descriptions of Sasanian judicial procedure we have suggest that they still would have been admissible before Sasanian judges, just at a lower level of evidentiary value. In other words, they still functioned under the auspices of the Sasanian judicial system, not in a fully autonomous Christian legal sphere. Additionally, Christian formulas and iconography on recent seal findings indicate that some Christians held imperially recognized offices, as does the Sasanian dynasty’s frequent interest in employing bishops in official capacities such as imperial embassies.65 Such individuals’ seals would presumably have granted marriage contracts full legitimacy, even if they did not conform to the Zoroastrian norms we see in the Middle Persian model contract. In these various ways, we should imagine Sasanian Christians operating under the purview of the Sasanian administration and its judicial apparatus even when they did not marry according to the same substantive norms as their Zoroastrian co-subjects.

Much as in the Roman Empire, the fact that marriage as a legal relationship did not fall under the exclusive purview of East Syrian law does not mean that ecclesiastical figures played no role in its administration. It is entirely likely that priests attended and blessed marriages, although the earliest positive evidence for an East Syrian liturgical ceremony of betrothal is not earlier than the seventh century.66 Furthermore, prohibitions of un-Christian marital practices form a significant part of East Syrian canon law from the Sasanian period. Mar Aba is exemplary in this respect; the distinctive Iranian forms of marriage enshrined in Sasanian law and common among some Iranian Christians—especially close-kin marriage and polygamy—compelled him to issue a substantial body of regulations for lay household life that became foundational to the later East Syrian legal tradition.67 Like their contemporaries to the west, East Syrian bishops such as Mar Aba used the same techniques of pastoral censure and exclusion from Christian communion to promote their notions of Christian sexual morality among the laity; East Syrian law sometimes ventured beyond the territory of Roman canon law only because a greater range of household forms were lawful and customary in the Iranian empire.

On the administrative side, we can certainly expect that many of the communal judicial venues at which Christians contracted marriages according to common law traditions were ecclesiastical audiences and that many of the local notables who served their communities as scribes, as witnesses, and in other judicial capacities had positions in the church. A recent survey of Syriac and Middle Persian seals belonging to Sasanian Christians, for example, includes a number that identify the holder as a deacon, priest, or metropolitan.68 In the late 600s, the Judicial Decisions of the East Syrian patriarch Hnanishoʿ I (r. 686–98) mention two marriage agreements that have been validated with the seals (Syriac singular ṭabʿā) of ecclesiastical officials, one a bishop and the other a traveling priest.69 These are likely examples of clergymen carrying on the legaladministrative functions of their Sasanian-era predecessors.

In sum, ecclesiastical figures in the Sasanian Empire were no doubt involved in the civil-legal business of the communities under their purview, including contracting marriages. But ecclesiastical law itself retained for the East Syrians a more restricted role. Rather than functioning as a comprehensive system that sealed off East Syrians from imperial legal institutions, it promoted appropriately Christian modes of conduct by regulating individual believers’ participation in Christian communion. Imperial and local civil traditions set the practical legal framework for marriage among Sasanian Christians in a manner similar to their Roman counterparts.

Religion, Magic, and Domesticity

Christian tradition put considerable claims on lay marriage and sexuality in the societies of late antiquity, but it ran up against other normative orders like imperial legal traditions, Greco-Roman sexual ethics, and Iranian marriage customs. As we have framed the story so far, much of this friction related to the public side of the institution of marriage: that is, the legal, moral, and theological statuses that those normative orders ascribed to men and women who had sex and cohabited with one another. For example, in the terms of Sasanian law a union between a woman and her nephew could be a valid marriage, while to East Syrian bishops it was unlawful fornication (zānyutā); sex between a man and a prostitute entailed no meaningful legal consequences in the Roman Empire, but it made the two into one flesh according to Christian theology. Before concluding, it is worth considering as well the relationship of Christian religiosity to some domestic aspects of late antique marriage, those that impinged less on public life. Late antique ecclesiastics prescribed norms for the private spaces of Christian households too; but again, practice varied considerably, and there is much evidence that the devotional side of household life was eclectic in ways that surreptitiously undermined the authority of Christian religious elites and their normative traditions.

Among the domestic activities that bore considerable attention from Christian theologians was sex itself, and we have seen that the prescription of monogamy and procreation characterized their traditions from an early date. Within the household, this translated into an emphasis on abstinence during fasting seasons and sexual restraint in general,70 as well as condemnation of the sexual exploitation of slaves. How completely the Christian moral-theological vision impelled householders to reorganize domestic life in these terms, which occurred behind closed doors in ways that divorce or taking a third spouse did not, varied over time and space. But if the lawfulness of specific sexual practices within domestic spaces received a good deal of ecclesiastical concern, it is also as important to recognize that late antique societies knew an entire realm of ritual practices related to sexuality, domesticity, and the inner affairs of households, neighborhoods, and kin networks far different from the doctrines and modes of piety prescribed by ecclesiastics. Essentially, we are dealing with what modern scholars call, with an imprecise but heuristically useful term, “magic”: a wide array of practices that tapped into the extrahuman, unseen powers that filled the universe in order to effect healing, protect against personal and familial calamities, or visit negative effects on one’s enemies.71 Such practices typically included “amulets, recitations of incantations, and performance of adjurational rituals.”72 These were frequently administered by learned practitioners other than religious professionals like bishops; in such cases, the latter tended to denigrate and proscribe magic as unlawful, unholy “sorcery” (Syriac ḥarrāshutā). Yet magic remained ubiquitous in the late antique Mediterranean world and western Asia, and it was practiced and patronized across the religious spectrum. Some Christians must have understood that magic fell outside the bounds of what the bishops considered properly Christian,73 but it remained an integral part of the life courses of untold numbers of laypeople formed less exclusively in the church’s high doctrine. Talismans, amulets, and adjurations were a way to look after one’s interests that coexisted largely unproblematically with one’s religious affiliation.

For our purposes, the important point is that magical practices were deeply connected to domestic realms over which more institutionalized normative traditions also claimed authority.74 If Christian soteriology was constructed around a particular ordering of human sexuality, much late antique magic was geared toward coping with the more immediate disorders and destructive possibilities of sex, as well as with other dangers that routinely beset ancient households—charming an indifferent beloved and attracting their desire, preventing against the dangers of childbirth, and warding off diseases that might befall loved ones are all common aims of late antique magical texts. Indeed, the fact that male religious professionals frequently conceptualized magic in negatively gendered terms—as arcane, unholy feminine knowledge—underscores its close connection to private, domestic spaces that bishops (as well as rabbis) could not always regulate so simply.75

The hundreds of Aramaic incantation bowls excavated from southern Iraq make for an evocative example of late antique domestic magic that involved religious-ritual practices and gender categories different from those of Christian orthodoxies. Dating to the sixth and seventh centuries (and perhaps to the fifth and eighth), the bowls are inscribed with incantations that seek healing or protection for the households of the clients who commissioned them: for themselves, their children, and their livestock and other property.76 The bowls are written in several scripts and dialects, including Jewish Aramaic, Mandaic, and Syriac. Client names indicate that individuals from across the religious spectrum—Zoroastrians, Jews, Christians, Mandaeans, Manicheans—made use of the bowls, and the incantations invoke a host of Hellenistic, Iranian, Jewish, and Christian deities, demons, and religious symbols.77 The incantations are also gendered in idiosyncratic ways. Clients are usually identified by their matronymics—that is, descent in the maternal line—which is incongruous with the largely patrilineal social organization of the Sasanian Empire, and may speak to the incantations’ connection to distinctly domestic realms understood in feminized terms.78 We can take as an example a bowl inscribed for one Bar-Sahde, a Christian name meaning “son of martyrs,” whom the inscription identifies further as the son of Ahata, a feminine Aramaic name. The magical practitioner who composed the incantation was presumably Jewish, to judge by its Hebrew script. The bowl’s target is a lilith, a female demon who has taken up residence “upon the threshold of the house of Bar-Sahde” and “strikes [and smites and k]ills boys and girls.” The lilith has effectively become a malevolent, unwanted member of Bar-Sahde’s household: the incantation expels her from it by writing her a deed of divorce so that she can no longer harm her human fellow householders, Bar-Sahde, his wife Aywi, and especially their children. In order to accomplish the divorce, the incantation invokes “the name of Joshua bar Peraḥia,” a rabbi whose demon-fighting powers appear often in bowl texts, as well as an Iranian entity, “Elisur Bagdana, the king of demons and dēvs, the great ruler of liliths.”79 After having the bowl inscribed, Bar-Sahde would have placed or buried it facedown in a corner of his house, the position in which excavations usually discovered the bowls, to trap or otherwise serve notice to the offending lilith.80

Bar-Sahde’s bowl vividly evokes a sphere of late antique household religiosity, intimately connected to sexual and familial order but largely outside the purview of Christian orthodoxies and formal hierarchies. To protect his family and household, Bar-Sahde took recourse to a Jewish magician and received an incantation invoking Jewish and Iranian powers. Besides the religious boundary crossing involved, the conspicuous feminine gendering of certain elements of Bar-Sahde’s incantation—its concern for matrilineal descent, the malevolent demon wife who must be divorced—evinces the domestic orientation of magical forms of ritual power and their difference from the more public, institutionalized ritual practices of the church (although the figure of the lilith is suggestive of a concern for the destructive potential of uncontrolled female sexuality common to many high-normative traditions as well).81 Late antique householders thus understood ritual practices like those surrounding Bar-Sahde’s bowl as specially attuned to the uncertainties and problems of desire, domesticity, and family life. Christian powers could certainly be harnessed to similar ends; psalm-chanting priests ward off demons in the story of Rabban Bar ʿEdta, for example, and East Syrian synodal canons mention learned and even ordained Christians who compose incantations, amulets, and auguries—indeed, we have plenty of incantation bowls written in Syriac, a number of which invoke the power of Christ and the Trinity.82 The telling point, however, is that high ecclesiastics condemned incantation writing, but not psalm chanting, as unlawful “demonic servitude” (pulḥānā d-shēdē): the former was part of a diverse tradition of ritual practice that bled out across the communal boundaries imagined by religious elites, operated outside the purview of more official hierarchies, and undermined Christian doctrine’s claim to exclusive authority over sexuality and domestic life. To high ecclesiastics, salvation came only through their prescribed forms of Christian piety and the singular mysteries of the Eucharist and baptism. But many laypeople decided they could not afford to bank on such an exclusivist model, and domestic religiosity, sexuality, and familial order in the late antique world were thus much more heterogeneous affairs than the normative ecclesiastical vision.

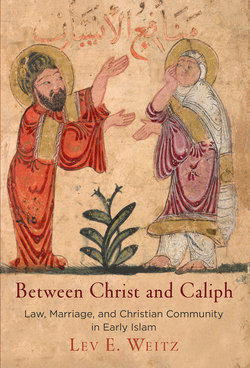

Figure 1. Syriac incantation bowl with an illustration of a magician. The incantation seeks protection against various demons for one Nuri and her house, husband, sons, and daughters. It invokes the Trinity, among other protective powers (see Moriggi, Corpus of Syriac Incantation Bowls, 27–31). The Catholic University of America, Semitics/ICOR Collections H156, with thanks to Dr. Monica Blanchard. Photo by author.

Marriage was foundational to the social organization of the late ancient world, as it had been to human societies for millennia. It was the chief institution around which the practices of social reproduction were organized, rendering sex between a man and a woman legitimate and defining the familial and kinship relations that transmitted property, status, and social identity. In the late antique eastern Roman and Sasanian empires, marriage bore considerable cultural weight and sat at the intersection of multiple normative orders: the imperial legal traditions that regulated the public meaning of cohabitation, sex, and associated property relations; religious traditions that ascribed cosmological significance to human sexuality and sought to direct its practice accordingly; and any number of local customs (regional, tribal, magical, etc.) by which subjects throughout the two empires conducted their domestic affairs.

While there was much interpenetration among these moral-legal-practical orders, a foundational story of late antique societies was the major challenge posed by Christian theologies of sex to other, long-established systems. In societies that by the sixth century were majority Christian as far east as the foothills of the Iranian Plateau, Christian traditions valorized virginity, downgraded the moral and theological significance of marriage and childbearing, and condemned a host of ancient and legally recognized practices: divorce, sex outside marriage for men, and, in the Sasanian Empire, close-kin unions and polygamy. But the Christian vision was not hegemonic. Even as Christian principles made their way piecemeal into Roman legislation and Christian clerics became influential community leaders, ecclesiastical law never had the authority to determine the public validity of marriage and the kinship and property relations that it established. Clerics preached, prescribed penitential punishments, and catechized, and all this undoubtedly prodded the sexual lives of laypeople toward the orthodox ideal, especially in cities and other territories with thick ecclesiastical presences. But it is clear that many of those ostensibly un-Christian practices associated with ancient marriage persisted in late antique societies, not least because they remained generally lawful in the eyes of the empires. The same held true for the rituals of domestic life, love, and religiosity decried as sorcery by ecclesiastics. Marriage remained an institution that inducted late antique subjects into multiple loyalties: to spouse, kin, and imperium as well as to the religious community.

The imperial orders of late antiquity, however, were soon to change. In the first half of the seventh century, armies from the Arabian Peninsula conquered the entire eastern Mediterranean world south and east of the Taurus Mountains. They brought with them a new religious dispensation, particular attitudes toward sex and marriage, and quickly developing ideas about how their Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, and other subjects were supposed to relate to their rule. The encounter with this new empire, the Islamic caliphate, transformed the social and intellectual worlds of the Middle East’s Christian communities over the course of its first three centuries. In particular, the articulation of caliphal structures motivated ecclesiastical leaders to reorganize Christian social patterns around the ancient institution of marriage in new and innovative ways.