Читать книгу Great Expeditions: 50 Journeys that changed our world - Levison Wood - Страница 15

ОглавлениеTop of the World

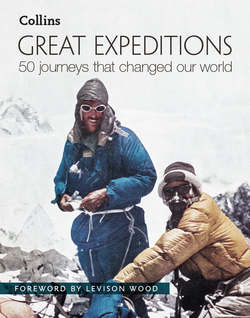

Hillary and Tenzing: Living in the death zone

“It is not the mountain we conquer but ourselves.

Sir Edmund Hillary

WHEN

1953

ENDEAVOUR

To climb Mount Everest, the highest peak on Earth, for the first time.

HARDSHIPS & DANGERS

Hillary and Norgay were venturing into a hostile zone where no human had ever been. They faced altitude sickness, exhaustion, frostbite from the severely low temperatures and whipping wind, as well as the climbing dangers of falls, avalanches and crevasses.

LEGACY

They successfully conquered the 8,848-metres (29,029-ft) high peak, a unique historical feat that captured the world’s imagination and ensured their lifelong recognition as heroes.

The heroic achivements of Hillary and Tenzing made headlines around the world. The Times of London produced a special supplement.

The human body is not built to survive at 8,800 metres (29,000 ft). The air is thin, containing only one third of the oxygen available at sea level. High-speed winds are a near constant presence, even when conditions are benign at lower altitudes. Cold is a deadly threat — the low air pressure sucks any warmth from the atmosphere even in high summer.

Each of these factors in isolation would present a life-threatening danger to any human being and the greater the height, the greater the hardship. When all three elements converge it is impossible for the body to withstand such pressures for any great length of time. The lack of oxygen places enormous strain on the heart and nervous system. The cold and wind will rip through any exposed flesh, causing frostbite and hypothermia within minutes of exposure. When a human being reaches such a destructively high altitude survival is impossible. The only option is to get down as quickly and safely as possible.

Two men above all others

On 29 May 1953, there were only two people in the world who truly understood what it was like to try and survive this far above sea level. No other humans had ever climbed so high. They were engaged in the fight of their lives. Each step was an ordeal. Every breath, despite the aid of the oxygen tanks they carried, was a separate torture as their lungs sucked for air. The wind buffeted them and threw shards of ice in their faces. They both knew their lives depended on turning back and reaching the relative safety of their camp several hundred metres below. But first they had a job to do. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had to complete their agonizing climb, only a further 48 metres, to the summit of the world’s highest mountain and claim their place in history.

The pair had just conquered the last technical climbing challenge on their ascent. They had scaled a sheer wall of rock and ice of around 12 metres (39 ft). If Edmund Hillary had been presented with such a rock face on a mountainside in his native New Zealand, he would have considered it no great challenge. But up in the death zone it was a stern examination of the men’s willpower, fitness and technical ability. It was also a test of their mental fortitude, for the climbers knew that once they reached the top of the cliff the summit would be theirs — so long as they could continue to keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Just one more step

The rock face would later be named the Hillary Step in honour of the first man to scale it. Today, climbers on their way to and from the summit use a series of fixed ropes to negotiate it, but Hillary and Tenzing had no such luxuries. After hauling themselves up the cliff face, the exhausted climbers were rewarded with a straightforward upward trek along a steadily-rising ridge.

Slowly but surely they made their way onwards. Just before noon, they could climb no higher. They had made the summit of Everest. Hillary turned to Tenzing and extended his hand, expecting Tenzing to reciprocate, only to be enveloped in an enthusiastic bearhug and a solid thump on the back. It was a rare break from 1950s reserve, but reflected the extreme excitement that both men were experiencing on finally achieving their goal.

Tenzing, photographed by Hillary, on the summit.

The search for lost souls

They took photographs and waved the flags of the United Kingdom, Nepal, India and the United Nations. They also undertook a search of the immediate area for any evidence that George Mallory and Sandy Irvine, two British climbers who had gone missing near the summit in 1924, had made it to the peak. There were no signs to suggest that they had. Hillary then buried a crucifix on the summit at the request of John Hunt the leader of the expeditionary party, while Tenzing left a food offering of some boiled sweets as a Buddhist tribute to the gods. Then, after 15 minutes on the roof of the world, the two friends turned and headed downhill.

By 1953, the competition to conquer the summit of the world’s highest peak had become a matter of national pride. For the British expedition, of which the New Zealander Hillary and the Nepalese Tenzing were a part, the late spring of 1953 would probably be their only chance to claim the summit of Everest for their country. A Swiss expedition had come within 250 metres (820 ft) of the summit the year before, and further Swiss and French expeditions would take place over the next two years.

Tenzing and Hillary may have been two small figures set against the vastness of the Himalayas, but they were members of one of the largest mountaineering expeditions ever assembled. The party consisted of 350 porters and twenty Sherpas in support of just ten climbers. They were not the first members of the expedition to strike out for the summit. On May 26, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans reached Everest’s South Summit – just 101 metres (331 ft) from the peak itself – before exhaustion and dwindling oxygen supplies forced them to abort their bid.

‘If you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself upward and forever upward, then you won’t see why we go.’

George Mallory

Now it’s our turn

The opportunity then fell to Hillary and Tenzing to strike for glory three days later. Tenzing was by far the most experienced Everest mountaineer in the party. Twelve months earlier, he had been part of the Swiss team that had reached 8,599 metres (28,200 ft) in their Everest attempt. Edmund Hillary was a veteran of several Himalayan expeditions. He made no secret of his confidence in his ability to reach the summit, and was also clear in his preference of Tenzing as his climbing partner. Hillary had reason to trust the Sherpa. At an earlier stage in the climb, Hillary had been plotting a route through an icefall when the ice gave way, plunging him into a crevasse. His life was saved by Tenzing, who managed to hastily fasten a rope round a pin secured in the ice and arrest Hillary’s fall.

The expedition used nine camps on their way to the summit.

Now as the pair made their descent down the mountain slopes, John Hunt waited for news of their fate. Hunt was based at Camp VI and watched intently as the two climbers plotted their way towards him. He examined their body language for some clue of whether their bid had been successful and came to the conclusion from the men’s demeanour that it had not. Hunt was wrong. He had mistaken their exhaustion for despondency and when Hillary and Tenzing were able to signal from some distance through a variety of finger pointing and arm waving, that they had indeed reached the peak, celebrations broke out within the expedition camp.

The Everest heroes celebrate with a cup of tea.

Crowning glory

For the British, the outpouring of national pride was not diminished by the fact that news of the successful summit expedition reached the United Kingdom on June 2, the day of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

Hillary, Tenzing and Hunt returned from the thin air as heroes. All three were given awards for their efforts. Hillary and Hunt both received knighthoods, while Tenzing was awarded the George Medal.

Hunt returned to the UK and became an influential figure in British politics. Hillary and Tenzing remained close until the latter’s death in 1986. Tenzing used his prominence to serve as an advocate for the rights of the Sherpa people and to warn against what he saw as the over-commercialization of Everest. Hillary joined an expedition to Antarctica, and in 1958 was part of the first team to reach the South Pole by vehicle after piloting a tractor across the vast polar icefields. In later years, he devoted much of his time to the Himalayan Trust which provided educational and medical support for impoverished communities in the Everest region.

Scaling other heights

With characteristic modesty, he said: ‘I have enjoyed great satisfaction from my climb of Everest and my trips to the poles. But there’s no doubt that my most worth-while things have been the building of schools and medical clinics.’

Sir Edmund Hillary died on 11 January 2008 in Auckland, New Zealand.

‘People do not decide to become extraordinary. They decide to accomplish extraordinary things.’

Sir Edmund Hillary

The jetstream blows a steady plume of snow and ice from Everest’s summit.