Читать книгу They Tore Out My Heart and Stomped That Sucker Flat - Lewis Grizzard - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Murmurings and Sad Love Songs

I’ve had trouble with my heart for as long as I can remember. Somebody keeps breaking it. I saw one of those public service announcements on late-night television. It offered some sort of pamphlet to young women who needed to learn how to say “No.”

Can you imagine that? Young women today have to write off to Washington for a pamphlet in order to learn how to say “No.” I thought it was something they were born with, like their inability to parallel park.

Girls never needed to look in a book to learn how to turn me down. Take when I was in high school. Those were timid, simpler times. All I wanted was to get kissed, but girls with whom I went out had a never-ending supply of excuses not to kiss me.

“I have a cold,” was one I heard over and over. For years, practically every girl I cornered in the back seat of a 1957 Chevrolet had a bad cold. I started carrying around my own aspirin and orange juice. It didn’t help.

Another excuse was, “I don’t want to smear my lipstick.”

“Go ahead and smear it,” I would say. “Helena Rubenstein is a personal friend of mine.”

My all-time favorite excuse for not kissing me was, “I don’t want to get into trouble.”

Don’t want to get into trouble? Was I asleep during biology class? You can “get into trouble” just by kissing?

The only way I ever got around all this was when I went to college and began to use a wily technique known as “practice kissing.” Here is how that worked:

“Let’s kiss,” I would say to my victim, “but it will just be for practice.”

“For practice?” she would ask.

“Sure,” I would continue, “we’ll kiss but it won’t count. We’ll do it just to see what we need to work on in case we ever decide to kiss for real.”

One particular evening it took a young Phi Mu and me nearly 450 practice kisses before we finally got it right.

It was a friend of mine, Ronnie Jenkins, who taught me my first real lesson about women, which was, you never can tell about women.

We were between our junior and senior years in high school and we thumbed to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, because we heard there were, in fact, fine young women there and you could buy beer legally at eighteen, which meant if you were sixteen, like us, you could even order it in a loud voice.

The best accommodations we could afford upon our eventual arrival at Myrtle Beach was the utility room behind The Waves Motel. We paid a woman who had no teeth two dollars a night for the privilege of sleeping amongst the discarded lounge chairs and deflated beach balls. There was no air conditioning, of course, but one side of the room was chicken wire, which allowed a soft, ocean breeze to creep in, not to mention the gnats and mosquitoes.

Our first night there, we were into modest involvement with two young women when a strange thing happened. A man, obviously very drunk, came out of nowhere and began climbing on the chicken wire that was one side of the utility room.

“Eileen!” screamed the man. “Are you in there, Eileen?”

We asked the two girls and neither was named Eileen, which was some relief to both of us.

“I’m looking for Eileen,” insisted the man, now fully suspended on the chicken wire.

“I’ll lean over and you can kiss my . . .” Ronnie began before I stopped him.

“Careful. Maybe he’s got a gun,” I said.

“I don’t care if he’s got a bazooka,” said Ronnie. “Look what I’ve got.”

From somewhere in the rubble of the utility room and in the dark of the interrupted moment of passion, Ronnie had found a large oar. He drew back with the oar and hit the chicken wire with great force. The man flew off the chicken wire and into the yard where he began to roll.

“Wilmington,” Ronnie said the next day. “Wilmington, North Carolina.”

“What’s Wilmington, North Carolina?” I asked.

“Where that sucker on that chicken wire stopped rolling after I hit him with the oar,” Ronnie laughed.

The two girls. They are what this story was to be about in the first place. We’d met these two girls on the beach, and what can you tell about girls? They asked us how old we were and since we were sixteen, we said we were nineteen. I was a sophomore at the University of Georgia, Ronnie was home on leave from the Marine Corps.

They said they were fifteen.

When we left Myrtle Beach, they gave us their address and phone number and told us if we were ever in Star, South Carolina, be sure to look them up.

Soon, Ronnie got the itch for another trip.

“Let’s go see those two girls we met at Myrtle Beach,” he said.

We raised thirty-two dollars between us, which was enough for a pint of Stillbrooks bourbon at the local Moose Club, if you knew the bartender, two one-way tickets on the Southern’s Piedmont from Atlanta to Greenville, thirty miles southeast of Star, and three dollars left.

We ran through the Stillbrooks and spend $2.75 on Coke to mix it with in the club car of the train. When we arrived in Greenville, all we had was a quarter.

We started walking.

“Our troubles are over,” said Ronnie all of a sudden.

“Our parents are here to take us home?” I asked, wishing out loud.

“No, stupid,” said Ronnie. “I see a pool hall. Watch me work.”

He was good at pool, Ronnie. Moved quickly around a table with confidence and finesse. Shot with one eye closed and the other watering from the smoke from his cigarette.

He fished our last quarter from his pocket and got into a game in no time. Eight-ball. “Let the kid break,” said Ronnie’s opponent. I didn’t like the man instantly. He had several tattoos on his arms and the toes were cut out of both his shoes and his fingers were yellow from the miles of Camel smoke that had oozed between them.

Quarter a game to start. Ronnie was on a roll. He was up a dollar. Then, two dollars. Then, three. I’d never been inside a pool hall before. When the regulars began to whisper and the man with the tattoos began to perspire and light one Camel off the other, I didn’t know it was time to be concerned for our lives.

Ronnie understood the situation perfectly. After he’d sunk the eight-ball in the right corner on a beautiful two-bank, he pocketed the last of the five ones his stick had brought forth from the table. And, just before the victim of Ronnie’s immense talent was about to bring forth some blood from Ronnie’s head with his own stick, Ronnie calmly asked the man, “Sir, do you have a daughter?”

“I ain’t got no daughter,” said the man.

“Too bad,” said Ronnie, still calm. “If you did and she had your looks, I hoped we could shoot one more game to see who enters her in the hog show at the county fair next year.”

The man was too full of rage to move for the split second it took Ronnie to grab me and have us six blocks away from the pool hall and gaining on downtown Greenville.

“Make a man mad enough,” Ronnie said, “and it’s as good as landing the first punch. He’s too stunned to move.”

Genius. Ronnie Jenkins was genius.

We ate a couple of cheeseburgers and bought a six-pack with the money Ronnie had won, and then we called the two girls in Star and they said their parents would be out of town until two o’clock in the morning and they couldn’t wait to see us, and would we bring them each a Hershey bar? Ronnie’s wanted nuts. Mine, plain.

We bought the Hershey bars with the last of the money and hitched a ride to Star, which was a small place. We eventually wound up on the girls’ front porch about ten o’clock. Nothing was moving inside.

“Maybe this isn’t the place,” I said.

“It’s the place,” said Ronnie, “they’re just bashful.”

When banging on the door and shouting didn’t work, Ronnie started singing some Beach Boys’ songs we had all listened to earlier at Myrtle Beach. Lights flicked on around the neighborhood, and that’s how he finally flushed out the girls.

“We didn’t think y’all would really come,” said Ronnie’s girl from behind the screen door of the house.

“Even brought the Hershey bars,” said Ronnie. “You nuts or plain?”

“Nuts,” she said. “Nadine is plain.”

Now, the girls are eating the candy bars behind the screen door and we’re still on the porch.

“Can we come in now?” Ronnie asked.

“Y’all can’t come in,” said Ronnie’s girl, the chocolate from her Hershey bar clinging to the side of her mouth. Neither one of them looked quite as pretty as they had at the beach, I was thinking to myself.

“Can’t come in?” Ronnie burst out, unbelieving.

“We ain’t old enough,” said the girl.

“You’re fifteen,” said Ronnie.

“Naw, we ain’t,” the girl insisted. “I’m thirteen, but Nadine ain’t but twelve. We lied to y’all at the beach. If daddy came home, he’d kill us and call the law on y’all.”

Ronnie tried to get what was left of the Hershey bar back, but the girl had bolted the screen door and had already eaten all the nuts anyway. I looked in one more time to see if I could get a last glance at Nadine, but all I could see was her back. She was feeding something to a cat. Probably the rest of her Hershey bar.

We were down after that. No girls. No money. We caught a ride with a brakeman on the Southern, who was heading back to Greenville, and he let us off at an all-night service station where Ronnie managed to get his arm up a vending machine and pull down two packs of toasted malted crackers for us to eat.

We sat there all night, waiting for the dawn when we’d hitch back home. Ronnie was quiet that night, deep in thought.

Just before daybreak, he turned to me and said, “I’ll bet that won’t be the last time either one of us gets made a fool of by a woman.”

Genius. The man was a genius. And a prophet, as well. I’m thirty-five now, and I’ve been married three times, already, which is even more of a feat when you consider I didn’t start until I was nineteen.

The first person I married was my childhood sweetheart. Lovely girl. Blonde. Sweet. I got fat eating her cooking. We lasted three years.

My first divorce, when I was twenty-two, was terrible. I was heartbroken over the entire matter, and for the first time in my life, I turned violent. Luckily, nobody was injured, however. My wife moved out and took an apartment. One night, I decided to go visit her and beg her to come home. Not only did I love her and miss her, but I didn’t know what to do about my underwear, which is a problem that befalls a lot of men when they divorce for the first time.

When I was a child and wanted a clean pair of underwear, I would go and look in my drawer, and there would always be clean underwear. Same when I was married for the first time. When my wife left me, my underwear no longer marched from where I dropped it, washed itself in the washing machine, and then marched back, folded itself, and returned to my drawer.

Nobody answered when I knocked on the door to my wife’s apartment. Suddenly, it occurred to me she was out with another man. I returned to my car in the parking lot and waited for them to come home. I would confront them both, I decided, and tell my wife of my love and she would come back to me and I would have clean underwear again.

I also decided she could be out with Dick the Bruiser, for all I knew, so I went to my truck and got my tire tool. I waited for several house. My wife and Dick the Bruiser never came home. I went to sleep with my tire tool in my lap. The next day, I found out my wife hadn’t been out with Dick the Bruiser, or anybody else. She had been home visiting her mother.

I felt like an idiot, having spend the night with a tire tool. I went to the laundromat and washed my underwear.

Three years later, I married again. We were in a terrible hurry to get it done. I called another friend of mine, Ludlow Porch, and asked if he would find a preacher as quickly as possible.

“Consider it done,” he said.

The preacher had a small, thin mustache and talked in a squeaky voice. He looked like a crooked Indian agent off Tales of Wells Fargo. He began the service by opening the Bible and squeaking out, “It says here . . .”

Three years later, when I divorced my second wife, Ludlow said, “I knew it probably wouldn’t work out anyway.”

“How did you know that?” I asked.

“Because I couldn’t find a real preacher for your wedding on that short of notice. The man that married you changes flats at the Texaco station near my house.”

I would have taken a tire tool to my friend Ludlow Porch, but he is built like Dick the Bruiser.

My second wife left me when we were living in Chicago. I had no alternative but to attempt to have dates with Northern women. Since I am a native Georgian, I had never been out with Northern women before. There are some distinct differences between Northern women and Southern women.

Southern women make better cooks than Northern women. Northern women make good cooks only if you like to eat things that still have their eyes, cooked in a big pot with asparagus, which would have been better off left as a house plant.

Southern women aren’t as mean as Northern women, either. Both bear watching closely, but a Southern woman will forgive you two or three times more than a Northern woman before she will pull a knife on you. Most important, Southern women know how to scrunch better. Scrunch is nothing dirty. It is where, on a cold night, you scrunch up together in order to get cozy and warm. And, Southern women can flat scrunch.

With this attitude, it is easy to see why I was usually very lonely in Chicago. One night, I found a bar in Chicago with a country music juke box. I had a few beers and watched a guy walk over to the juke box with a handful of quarters.

My second wife had split and I was far from home, adrift on a lonely sea.

“Play a love song,” I said to the guy at the juke box.

I needed it badly. One thing about country music. It has something to say.

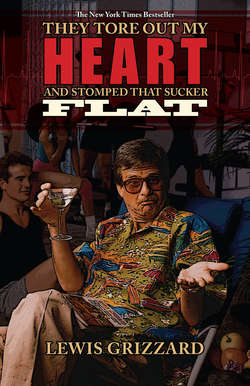

They guy played a song entitled “She Tore Out My Heart and Stomped the Sucker Flat.”

I left the bar and went home and washed my underwear.

I was fifteen the first time I found out I had trouble with my heart that didn’t relate to falling in or out of love. A country doctor listened to it beat and was not pleased with what he heard.

“Hmmmmm,” said the doctor, moving his stethoscope to another position.

I didn’t know it at the time, but a patient can learn a great deal about his condition simply by listening to the sounds the doctor makes while he conducts his examination.

“Hmmmmm” means there is something very interesting going on inside you. A policeman makes the same sound when he pulls you over and there is an empty bottle of Gallo Thunderbird wine on the seat next to you.

“Ahhhhhh” means he just remembered the last time he heard something going on inside you. It was back in medical school the day he was assigned his first cadaver.

“Oooooh” means that, compared to you, the cadaver was in good health.

“What is the problem, doctor?” I asked.

“Heart murmur,” he answered.

“Nothing to worry about,” he said. “You’ll probably grow right out of it.”

I didn’t worry about it. I went right along with the normal life of the next demented child. I played sports throughout high school. I went off to college and took up drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. I had other physicals.

“Hmmmm” is the sound doctors would always make when they listened to my heart.

The diagnosis was always “heart murmur. Nothing to worry about. You’ll probably outgrow it.”

I didn’t outgrow it. Came time for me to leave college. It was 1968. Recall the unpleasantness in Vietnam that was raging at the time? The government was insistent I go and take a part. I had another physical.

“Oooooh,” said the doctor.

I didn’t have a heart murmur any more. The murmur, or strange sound emanating from my heart, turned out to be something else.

I was twenty-one. The diagnosis was aortic insufficiency. Doctors can spend hours explaining. I can do it much more quickly.

In the normal heart, the aortic valve—from which blood leaves the heart and goes out into the rest of the body—contains three leaflets, or cusps, which open when the blood is forced out and then close tightly together so that none of the blood can leak back inside the heart.

The doctor’s diagnosis was that I had been born with only TWO leaflets in my aortic valve. I was born in 1946, right after the Big War. Perhaps there was a shortage of aortic leaflets.

Regardless, each time my heart pumped blood out, some of the blood would seep back into my heart, causing the “murmur” sound. On the next beat, my heart would have to pump that much harder.

“It’s like taking three steps and then falling back two to make one,” the doctor explained.

I was frightened of course.

“You can forget the service,” said the doctor. “They’ll never let you in with an aortic insufficiency.”

I wasn’t frightened after he said that. Better an aortic insufficiency than a bullet from a Russian-made AK-47 right between my eyes, I figured.

The doctor made it quite clear to me. No big problem at the moment, he said. A young heart can withstand a great deal.

“But someday,” said the doctor, “someday, you will have to have that valve replaced.”

Someday. To a young man who has fallen in love in a motel utility room in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, who has practiced-kissed Phi Mu’s, and who has just been given a reprieve from the mud and blood of Vietnam, someday never comes.