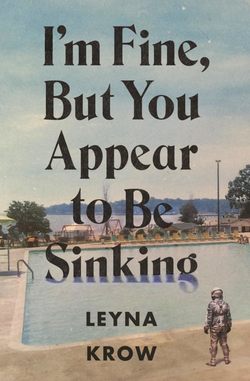

Читать книгу I'm Fine, But You Appear to Be Sinking - Leyna Krow - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI’m Fine,

But You

Appear

to Be

Sinking

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 1

It’s just me, Gideon, and Plymouth now.

Strangely, the Artemis seems smaller with only the three of us onboard. At ten people, our 112-foot trimaran felt spacious, with plenty of room for everyone to go about their respective tasks. There was a constant human hum, but we weren’t on top of each other.

Now Gideon and I can’t seem to escape ourselves and Plymouth is always under foot. His barking echoes through the narrow hatchways. Shrunken—that’s how this whole arrangement feels.

The Pacific Ocean, however, is the same size it’s always been.

I don’t want to admit anxiety or desperation. That seems unprofessional. But if the boat has moved in recent days, it has been by its own accord and certainly not in any productive direction. We lack the necessary manpower and know-how. I try not to blame Gideon for this. He is, after all, only an intern.

So far, I’ve managed to avoid making hasty decisions. Inaction, for the time being, seems the safest course of action. The trip has been so marred already by the pitfall of optimism.

When the others started making their preparations, the clouds were high. By the time they had descended and darkened, the inflatable skiff, Righteous Fury, had already been lowered off the stern of the Artemis and into the sea. The protest banners were unfurled and the megaphone batteries charged. It occurs to me now that reasonable men with reasonable aims would have called for a rain check. That’s the problem with radicals—they rarely take weather into account.

Gideon had been left behind to keep watch. Together, we observed from the bow as the skiff containing our eight crewmates set off after a whaling ship of unknown nationality. Gideon held a digital video camera. His face was a wide grin.

“Civil disobedience is the highest form of civic participation,” he informed me.

I asked whether the maxim still applied in ungovernable waters where there is no civil or civic anything to speak of. Gideon shook his head and told me that right and wrong transcend international boundaries.

The whaling ship had been spotted near the horizon that morning by Gideon himself. It was the first encounter of the trip and the crew’s excitement was palpable. I watched as they readied themselves, speaking hurriedly, faces flushed. They knew how to say, “You are in violation of the Endangered Species Act and International Whaling Convention” in thirteen languages. A few had worked out phrases of their own such as, “How would you like to be harpooned?” and, “Every humpback is someone’s child.” Though technically it would be more accurate to say, “Every humpback is someone’s calf,” but I suppose that doesn’t have quite the same ring.

If the banner waving and slogan shouting did not convince the whalers to turn back, I’d been told by certain crew members that they were prepared to board the rogue vessel. No one would say what might happen once they were inside.

Did this necessity ever come to pass? We’ll never know. The skiff was not yet in shouting distance of the whalers when the sky, already gray and noisy, closed in on us, obstructing our view of the only other souls Gideon or I knew in the entire hemisphere. For the next five hours, we were no more than a buoy, bobbing alone in the sputtering froth of warm rain and salty wind.

When the clouds lifted, the whaling vessel was gone from the horizon and so was the skiff Righteous Fury.

It should be noted that the day of the storm, it was Nelson’s turn in the galley. Gideon and I were unable to reach an amicable agreement as to who should pick up the slack and make dinner. And so we simply went without eating.

Now, I have designated Gideon as the all-time breadwinner, and baker (if I may be so bold as to extend the analogy). There are plenty of canned goods in the galley, but the supply is certainly not infinite. I suggested we ought to supplement these items with fresh fish. This part of the ocean is rich with life, after all. Gideon was not initially pleased with the idea, claiming he is an ultra-strict vegan and refuses to eat anything that casts a shadow. I told him this was no excuse for shirking his responsibility to the remaining crewmembers, myself and Plymouth specifically, but he insisted. So I’ve had to find other ways of motivating him.

“Gideon,” I say when I get hungry, “catch me some fish, or I’m going to kill your dog and eat it.” He practically jumps for his pole every time.

The same threat works for getting other tasks done as well.

“Gideon, straighten the lines, or I’ll kill your dog and eat it.” “Gideon, empty the bilge, or I’ll kill your dog and eat it.” “Gideon, bring me the binoculars...” You get the idea.

Unfortunately, this ploy may have a limited lifespan. Gideon has already succeeded in hiding almost all the knives onboard and has begun removing cleats and other metal affixtures from the deck for good measure.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 4

There’s been no wind for days, as if the ocean wore itself out swallowing our comrades. I lick my lips and feel nothing against them. It’s almost a relief. I know my limitations.

I wish I could say the same for my shipmates.

Gideon paces the deck in the heat of the afternoon, Plymouth always nearby. He fiddles with ropes and cranks and looks expectantly toward the sky and then down into the water. He wants to know what we are going to do.

I keep telling him there are Quaaludes in my toiletries kit and grain alcohol in the galley and we can worry about further logistics once those are gone. He finds this answer unsatisfying.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 5

At noon, Gideon called to me, saying I should come up top with him to look at the octopus. But I stayed put. I’ve seen the octopus before and what’s more, as I’ve already told Gideon, it’s not an octopus. It’s a giant squid. Octopuses don’t get that large.

Gideon believes it’s an omen, a harbinger of good luck. We first saw it the day after the storm—a shimmering, near-translucent mass passing beneath us. It was gone in an instant, but the goose bumps on my arms lingered for half an hour. Now, the squid stays longer, hovering under the Artemis, doing God knows what.

Gideon thinks the creature has come to comfort us in our time of loss. I think it’s stalking us. It senses our weakness and is biding its time.

I hear its tentacles pressing against the hull at night. Suction cups attaching and releasing, toying with its prey until the right moment. It would eat us whole in the crunchy wrapping of our fiberglass boat if it could.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 7

It should be known that I am not Captain C.J. Wyle.

True, this is his journal. But I commandeered it after the storm, ripped out his notes on the trip thus far (going well, he felt), and dropped them overboard in hopes that they might meet up with their original owner.

It’s not that I don’t have notebooks of my own. I do. And pens, and a camera, and a digital voice recording device—all the necessary tools for a member of the fourth estate.

My assignment, for Popular Anarchist Quarterly, was to accompany the team from a newly formed oceanic protection agency (as they like to be called) on their maiden voyage. The organization, operating under the handle Save Our Sea Mammals, or SOSM, is in its infancy, but its organizers are hardly unknowns in the world of nautical activism. In fact, just last year, I did a profile on SOSM founder Erica Luntz for her work in various West Coast ports of call sabotaging naval icebreakers bound for the North Pole. These boats, it seems, present a terrible danger to both polar bears and their adorable prey.

The story was a hit with Popular Anarchist readers and my editors were keen for a follow-up with Luntz on her newest venture. For five weeks of embedded reporting, I was promised the cover and an eight-page spread.

Does this seem like a lot to go through for top billing in a niche magazine? Perhaps. But let me assure you, Popular Anarchist is the premier journal for radical discourse. It’s a thoughtful publication. No syndicalist screeds or dirty bomb recipes to be found in its pages. Rather, it promotes a more moderate approach for smashing the state.

So this is kind of a big break for me. Especially because—I’ll be the first to admit—I am not a very good reporter. I have a tendency to sacrifice accuracy for style. I’d rather write something that sounds good than something that’s true. I never lie. But I do embellish. For example, whenever I am writing about a group of people coming together for any purpose, I always like to say, “a crowd gathered,” no matter how many people there really were, crowd-like or not.

I hope you can see then why I might want to keep a record of these events separate from my work. It’s a matter of clarity and veracity.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 8

Around noon, a crowd gathered at the stern. Someone had spotted something. Gideon, Plymouth, and I stared out at a single blemish in the otherwise unmarred blue of the stupid endless sky. The blemish appeared to be moving toward us.

“It’s a plane,” Gideon said with the real excitement of someone who really believes he’s looking at a real airplane.

He took off his bright yellow SOSM t-shirt and waved it above his head.

I looked up at the thing, silent and encased in atmosphere. Even far away it was too small to be a plane.

“It’s only a bird,” I said. “Probably an albatross.”

“No. There’s no such thing as an albatross,” Gideon countered, still whipping his shirt around. “They’re just something Disney made up for that movie about the mice who go to Australia.”

“You’re thinking of pterodactyls,” I said. “And The Land Before Time wasn’t a Disney film. It was Spielberg.”

“Pterodactyls? No, you’re thinking of mastodons. And that’s not even the right movie anyway.”

“A mastodon doesn’t fly,” I corrected. “It’s like a woolly mammoth. There’s no way that is a mastodon.”

I pointed to the object in the sky for emphasis, but it was gone.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 9

This has to be the sleepiest dog on Earth. Or at least the sleepiest dog in the Pacific Ocean. I’m watching Plymouth nap in the skinny shade of a portside fender. It’s not the rabbit-chasing-dream kind of dog nap. I’d take him for dead if not for the gentle rise and fall of his rib cage.

Has there been a change in his behavior since the storm? Before, I didn’t pay him much attention beyond the passing pat on the head. Clearly, he’s upset. But is it just the weather (too hot for so much fur), or does he sense the gravity of his circumstances?

Gideon says Plymouth is part Saint Bernard. Funny, I would have guessed beagle. It’s in the markings, not the size, Gideon insists. I insist that if Plymouth is a Saint Bernard, he ought to do a better job of rescuing us and bringing me tiny barrels of brandy while we wait.

In the evenings, Plymouth wakes up and sticks his head through the guardrails, barking from time to time at something below us neither Gideon or I can see. Phantom sea-mailmen? I have suspicions otherwise and it makes the hair on the back of my neck rise like the first touch from something deep-water-cold and deliberate.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 14

I have come to suspect two things about Gideon. First, I suspect that Gideon is not his real name. It’s a terribly inappropriate handle for someone so gawky, so freckled, so sullen. Even when he was in the womb, his parents must have known better. I broached this subject delicately this morning while we were sunning ourselves topside, or as he likes to call it, “Keeping lookout for rescue parties.”

“Was Plymouth always called Plymouth?” I asked.

Upon hearing his name, the dog moved his tongue back into his heat-addled mouth and wagged his tail.

“What do you mean?” Gideon asked.

“What I said. Has this animal, now or prior, in this state or any other, been known by a different name?”

“Yeah. When I got him from the shelter he had another name,” Gideon said.

“And you elected to change it on his behalf? Did you consult with him first?”

“He’s my dog, I can call him what I want.”

I conceded this was fair.

“Besides,” Gideon said, “some names are just stupid names.”

“Such as?”

Gideon tousled the dog’s too-long ears.

“Andrew, for one,” he said.

“That is indeed a terrible name for a dog,” I agreed.

I asked him how he’d settled on the new title instead.

“It’s from the Bible,” Gideon said. He said it the way little boys state facts they believe ought to be obvious to everyone everywhere and how could you be so dumb?

This is the other thing I suspect of Gideon, that he is not of age. What age he isn’t of, I can’t be sure. Certainly not of drinking age. Voting age, maybe. That he is not yet of shaving-regularly age doesn’t help his case. We’ve been rationing water for ten days and the best he’s managed in that time is some chin scruff.

But the point I’m trying to make is that Gideon is a very private individual. Not one to talk about his personal life. Then, who is? But I have this amazing ability—a super power if you will. It turns out, when I am trapped at sea on a trimaran for two weeks with just one other person, I can see into that person’s inner-most being.

What do I know about Gideon? Somewhere, a sunny antiseptic suburb is missing a punk kid. A black-jeans-wearing, Dead-Kennedys-listening, establishment-dissing, animal rights-espousing cliché with a skateboard.

Too much of a boy for the pirating life. But oh, these “oceanic activists,” they’ll take anyone with a student ID card, slap a life jacket on them, and call them an “intern.” When I first came to this conclusion, I was horrified for Gideon, taken advantage of like that.

“Do your parents know where you are?” I asked.

“No one knows where I am!” he shouted.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 15

A trimaran, in case you don’t know, is a kind of sailboat with three hulls. There’s one big hull in the middle where all the stuff goes—the rooms, the pipes, the wires, the food, the maps, the spoons, the salad forks, the people, etc. On either side are two smaller hulls. They are like little hull training wheels. When the boat is floating along straight up and down, they barely touch the water. Only when we tip sharply to one side or the other, does an auxiliary hull make itself useful. I keep thinking there is a metaphor to be drawn from this. But I can’t decide what for.

My earlier notes indicate that this particular trimaran was a gift to SOSM from a generous leftist entrepreneur who once used it to sail around the world in some manner of record time. It should be noted that he was assisted by a crew of six for this task, none of whom were journalists, teenagers, or dogs.

To keep the craft light, and the sport of racing pure, the Artemis does not have a motor. There is an engraving at the helm to remind us this (as if we could forget). In narrow calligraphy, it says “At the mercy of the winds and our wits. Godspeed.” Or, that’s what it used to say. Gideon has since destroyed the offending inscription, jabbing at it one night with a Bic pen until the letters began to chip away, the pen fell apart, and his own hands could do no more good. Now it is only a jagged wooden scar, streaked with black ink and knuckle blood. Our new motto. Our epitaph.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 17

My knowledge of oceanography is limited. Ditto for cartography, marine biology, maritime law, and even basic geography. Never before have I regretted my liberal arts education with such immediacy. Sailboats cannot be piloted by rigorous discourse on Kant or Wittgenstein.

Foucault would have loved this predicament, I like to think.

My fourth grade science book was called The Oceans and had a picture of a coral reef on the front with a single tropical fish. The fish was peeking out from behind the reef, like he’d just been caught in the act of something embarrassing. If only I could remember what was inside that tome so clearly.

What’s the difference between a dolphin and a porpoise? What makes phosphorescents light up? Is a shark a mammal or a fish? The Polynesians invented the sailboat. Somewhere near here is the world’s deepest ocean trench. Squid can hear through their eyes. Yes, that’s right, I know about the way you watch and listen at the same time.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 18

As a practical measure, Gideon and I have divided the Artemis in half. He gets the front with the crew’s quarters, galley, and navigation suite. I get the back with the captain’s berth, the head, and a room filled with various important-looking boat parts.

Plymouth is free to roam where he wants. Despite my threats, I wish him no harm. In fact, I like having him sleep in my cabin at night. He is pleasant company. And his breathing covers up other sounds—wave-lapping and ship-creaking and tentacle-suctioning and such.

Gideon and I are both guilty of trespassing, however. Early on after the storm, I snuck into the galley and took all of the Crystal Light lemonade packets in hopes of warding off scurvy. They are stashed beneath my (formerly C.J. Wyle’s) mattress. I’ve also gone through most of the crew’s footlockers and pilfered the items I like. Gideon appeared yesterday wearing a Panama hat I’d already taken from either Erica or Nelson, so clearly he’s been in here too. But I didn’t say anything about it. Thieves make terrible police.

Then, today, I caught Gideon in my own quarters. He was riffling about in the captain’s shelves. I grabbed him by his studded belt and threatened him with Court Martial.

“This is high treason, sailor,” I said.

He apologized and explained he was only looking for the manual.

I told him there was a manual for the espresso machine in the galley, and that I had last seen it under the cast iron skillet along with The Joy of Cooking.

“No,” he said, “the manual for the boat.”

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 23

This ocean reminds me of someplace I’ve been before. I don’t want to give the impression that I am one of those worldly, traveling reporters, always on assignment to exotic locales. I’ve visited Hemingway’s Paris, yes, and hated it. I spent one semester during college in central northern Europe for my major in western studies. I’ve been to Trinidad, but not Tobago. And I’ve only seen one species of penguin in the wild.

But somehow this spot—this water and sky and nothing else—is so familiar. I’ve decided it’s not what’s here, but what is absent that I am recalling. Although that’s a depressing way to consider my life on the whole.

I hate to think I’ve always been this adrift.

I’ve just now remembered I have parents who are disappointed. I have a half-finished novel in a drawer. I have dirty dishes in a shallow apartment sink. A single neglected houseplant. A certificate that reads “One Year Sober.” A nug of hash I was too anxious to take on the plane, squirreled away in the glove compartment of my car in Lot C16 at Boston Logan. Unreturned phone calls. I have loans I’ll never pay back.

I’d gladly trade all my Crystal Light packets for that hash.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 25

Gideon has been feeding the squid. He drops overboard my post-meal scraps of fish that even Plymouth rejects.

“I’m trying to teach the octopus to eat out of my hand,” he explained when I questioned him about this behavior.

“I don’t think squid eat fish,” I told him. “I think they primarily eat plankton, which they suck in through their strainer-like teeth.”

But my doubt did nothing to discourage the boy and after a few moments, bubbles the size of dinner plates appeared at the surface. Something had taken Gideon’s offering.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 26

Have you ever seen a humpback whale? They are ugly as sin. Really and truly unattractive creatures. Not that this justifies their being shot at from boats and then hacked up and refined into restorative powders and sold by the ounce to Japanese businessmen. I’m just saying this cause might be easier to get behind if the animal in question were a bit cuddlier. Or at the very least, not covered in humps.

Yet, through it all, Gideon has remained loyal, insisting that his fellow crewmates perished in the name of maritime justice.

“But what about us, then?” I ask.

Gideon is not, as a general rule, tolerant of this style of questioning.

I worry I’ve ceased to be an objective observer of this trip and its crew (living and not). I feel badly about this. Clearly, I am in breach of my original contract with Popular Anarchist Quarterly, having become too personally involved with my subject matter. Yesterday, I got out my tape recorder and tried to interview Plymouth about the mission statement of the organization and its aims for the future. He chose not to speak on the record. Pity. I have been thinking that perhaps if I can make sense of my earlier notes, I could still file my story via message-in-a-bottle. But the words on those wrinkled yellow pages appear as hieroglyphics. They are from another time and make no sense in this new, modern world. My handwriting doesn’t even look like that anymore.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, February 27

I’d like to make an amendment to my last entry, if I may. The truth of it is, even if I could file my story, I wouldn’t want to. Because I didn’t do what I was supposed to do. I’m here on the Artemis, yes, but that wasn’t my assignment. My assignment was to follow Erica and her crew and report back on their vision, their methods, their passions, their most human moments. That’s what it means to be embedded.

I should have been on the Righteous Fury when it motored bravely into that storm. I should have been at the very front, camera and tape recorder at the ready.

But instead, when Erica handed me my life jacket, I handed it right back. Not because I knew anything about the impending storm, but simply and inexcusably because I was afraid. I didn’t even know what there was to be afraid of but I knew I was afraid and so I said, “No, I’ll be just fine watching from the boat with Gideon, thanks.” And off they went, without me, rendering my very being on the trip purposeless.

Of all the many, many things I’ve been ashamed of in my life, I suspect this is perhaps the most shameful of all. The reason: no one knows I’ve done it but me and I still feel ashamed.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, March 2

Water has become a problem. The greatest irony of the ocean is... do I even need to say it? Every morning, we ration out our daily liquids into shot glasses. I’ve given up on the trick of swallowing my own spit for sustenance; the placebo of it’s gone and I’m only left thirstier.

Gideon’s been thinking about trying to drink his own piss a la Kevin Costner in Waterworld. I see him eyeing the near-amber stream he allows to trickle off the side of the boat every fourteen hours or so. But Mr. Costner had a special machine for that, I remind him. He reminds me not to watch while he pees.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, March 3

I wonder about the individuals with whom we used to share this boat. What kind of people choose the seafaring life, anyway? They say the ocean is the last refuge of the damned.

No, that’s prayer. Prayer is the last refuge of the damned. Regardless.

Sometimes, Gideon stands on the deck with his head back, arms spread, baggy t-shirt hanging from his sun-blistered shoulders like a sail. What is he offering up?

Or beckoning in?

I don’t want to be alone out here either.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, March 4

Gideon has begun jettisoning things into the sea. First, his video camera, battery-power long since exhausted. Then pots and pans, socks and shoes, etc. He thinks if the boat is lighter, it will have an easier time floating somewhere, as if it were the weight that holds us to the middle of the ocean.

“That looks fun,” I told him after he tossed a half-gallon jug of hand sanitizer over the side of the boat this morning. He didn’t answer me, but I decided to join in anyway.

Inside the cabin—which had already grown muggy and airless in the heat—I moved aside boxes of charts and nautical instruments until I found the corpse of the Artemis’ shipboard communication system.

Early on in the trip, Erica dismantled the radio, saying any attempt to contact authorities for any purpose would be considered an act of mutiny. At the time, this proclamation seemed foolhardy, but as an observer and not an active crewmember, I didn’t feel it was my place to object. Now I’m pretty pissed about it though.

I pushed the stray knobs and fuses back into their metal casing, picked the whole contraption up, then tied its chords into a ball and carried it back up top. It wasn’t a particularly heavy device, but it made a cathartic splash none the less.

“Hey! Hey, what the fuck?” Gideon barked. “I was using that.”

I kicked over the few extra pieces that had fallen to the deck, tidying up.

“What the fuck?” Gideon said again. “What’s wrong with you?”

“Sorry, pal. Didn’t know you were playing dollhouse with it. I promise I’ll get you some new Lincoln Logs for Christmas.”

“I wasn’t playing. I was fixing it. I was going to fix it.” His skinny hands balled tight into skinny fists, cracked fingernails digging into his own flesh. He looked as if he might hit me.

“I ought to throw you overboard,” he said. He unclenched his hands and took hold of the hem of my shirt. His grip was surprisingly light. I made no move to shake him off.

“You weren’t going to fix the radio,” I said. “It was a useless, broken thing.”

“You’re a useless, broken thing!” Gideon’s voice split on “broken.” His breath smelled like an old man’s, like something was decaying inside of him. I noticed for the first time that Gideon has lost two teeth since the start of the trip—fairly prominent ones. Blood leaked from his gums as he spoke. I felt around in my own mouth with my tongue to see if I had suffered a similar misfortune, but everything seemed intact.

“Nope, still okay,” I said.

Gideon blinked twice, shaking his head. He let go of my shirt and turned away from me, stomping across the deck to where Plymouth lay dozing, unaware of what had just transpired. I watched Gideon nuzzle his face against the dog and whisper conspiratorially to him. After a moment, Plymouth responded with a volley of face licks.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, March 5

Today, Gideon is giving me the silent treatment. He refuses to leave his quarters except to cook and eat. I worry he may be ill. The quiet is eerie and I find myself willing Plymouth to bark just for distraction.

Shortly after dusk, I opened Gideon’s door and asked if he wanted to play cards, maybe some Old Maid or Go Fish. He only glared at me from his narrow cot, burrowing his body deeper into the stale sheets.

I’ve concluded the youth today have no patience for games of chance.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, March 6

Last night, the wind picked up again and I could hear the sky eating up the stars, cannibalizing itself. From my bed, I yelled to Gideon to raise the sails, thinking we might use those early gusts to push us somewhere. He yelled back that I ought to go fuck myself.

For hours, we bobbed back and forth. I am getting pretty good at not puking in such conditions. I lay in bed, thinking still and level thoughts, and listening to the Artemis creak and shudder. At the worst of it, I was convinced I heard the suction cups. It’s come to pull us apart as an ally of the ocean, I thought. But there was no added violence from the squid. It was as if he’d found us, lonely in the storm, and was just holding on.

From the notebook of Captain C.J. Wyle, March 7

This morning, Gideon came down into my berth, dragging behind him all the line from the main sail.

“I’m going to lasso the octopus,” he announced. It was the second time he’d spoken to me in three days.

“Excellent,” I said. “That will be good eating.”

“No. I am going to lasso it so it will pull us with it to shore.”

I told him squid don’t live on shore. They live on the bottom of the ocean. This much I am sure of. I remember the page from my science book—colorful, with drawings and a fact box in bold text asking, “Did you know?” This knowledge is unsoiled by childhood forgetfulness or adult self-doubt. “I stake my reputation on it,” I said.

Gideon shook his head. No, he insisted, if only he could get a line around the octopus, it would take us someplace safe.

I looked into his jaundiced eyes. Crusted and earnest, they begged for something far, far beyond my capacity to deliver. Why hadn’t he ever asked before? I reached out and let my hand rest at the base of Gideon’s neck. I patted him between his jutting shoulder blades. People who are friends do this for one another. I’ve seen video footage of it. I remember a different place where I knew what it felt like to be touched and held.

I told Gideon I would help. I told him it was the best plan anyone had come up with.

We tied a giant slipknot and anchored the rope to the guardrails (all the cleats are gone, if you recall). I shook Plymouth awake and clicked and whistled for him to join us. It seemed important that everyone be present. Gideon dropped our best rations overboard, wiping fish remnants and coffee grounds off his hands onto his shirt and then removing the neon garment and placing it into the sea as well.

We sat together at the bow of the Artemis, in the aching sunlight, waiting.