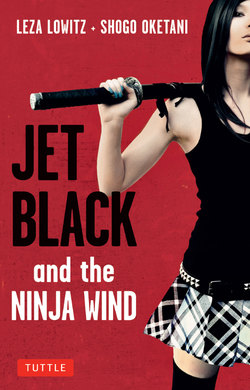

Читать книгу Jet Black and the Ninja Wind - Leza Lowitz - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 6

お祖父さん Ojiisan

Grandfather

An old man with white hair stood at a stone wall. Though eighty, he looked powerful and strong. His skin was smooth and brown, his eyes were—how strange—blue! Just like Hiro had said.

“It’s Rika!” Hiro said. “She’s finally here. Now we can–”

Ojiisan silenced him with a quick gesture, turning back to Jet.

“Granddaughter,” he said gently, “thank you for coming all this way.” Jet was happy to see a smile on his lips. She wasn’t sure he’d welcome her, but his blue eyes twinkled warmly, and she felt herself relax.

“You look so much like your mother,” he said in halting English.

He waved his hand, beckoning her closer. “I’m Masakichi. Hiro calls me Ojiisan, Grandpa, and you can, too.”

He bowed deeply. She held out her hand. He laughed, held out his hand and took Jet’s, shaking it vigorously. His fingers were calloused and rough.

Jet held on tightly as they made their way down the hill. The sun was descending in the distance, casting a golden hue on the valley. Hiro followed close, his nervous energy worrying Jet, making her think of her mother’s warning.

But Ojiisan didn’t seem worried. Jet felt that he’d known she was coming, even though she’d had no way to tell him, and had been warned by J-Bird she must arrive in secrecy.

Jet took a deep breath. The forest was preparing for winter, its smell different from the Southwestern desert’s juniper, piñon, sage. That smell had been brisk and bracing. This forest was smoky, like freshly cut wood.

Ojiisan motioned to a two-story wooden farmhouse with a triangular thatched roof. Just like Satoko had described it.

“We’re home. It’s cold, so let’s go inside.”

He placed a hand on Jet’s back, guiding her into the stone foyer. He took off his muddy boots, shook them, and gestured to Jet to do the same. She removed her own, the wooden floor smooth under her tired feet. The house smelled of moss and rain, as if she were still outdoors.

“Ojiisan,” Jet said and handed her grandfather the box. “This is…”

Masakichi closed his eyes briefly and bowed low, understanding. He took the box gently into his hands, nodding at Jet to follow him as he carried it into a room with tatami mat floors and placed it on the Buddhist altar. He knelt to light a stick of incense and handed one to Jet so she could do the same. Fragrant cedar smoke swirled in the room, much sweeter than the piñon she was used to.

He closed his eyes and clasped his hands at his heart. “Namu amida butsu,” he intoned. I pray to Lord Buddha. Jet repeated the words, calling forth the benevolent one. She felt Satoko with them almost as strongly as if she were really there. A chill ran up her spine.

After a while, Masakichi stood and went into the kitchen, motioning for Jet to follow.

The kitchen had a dirt floor and stone oven in the corner, blackened with soot. An iron pot with a thick, wooden lid gave off steam. There was a rusty water pump and a propane burner, too.

Masakichi stood a moment, as if remembering where he was, or trying to let go of his sadness.

“This house is over two hundred years old,” he said. “I used to cook with Satoko here, just like my own parents cooked here with me.”

“Two hundred years? Wow,” Jet nodded, trying to imagine her mother at eighteen, in the same kitchen she was now standing in. “We never stayed in one place long enough to gather dust, let alone memories!”

Ojiisan’s lip quivered and he looked away.

Jet wished she hadn’t said anything. Awkwardly, she ran her fingers along the bowls, the stove, even crouched to slide them along the smooth wooden floor—touching the things her mother might have touched. Why couldn’t they have come back together?

Jet didn’t want to barrage her grandfather with questions though; they’d only just met. She tried to relax and see into his feelings, but her stomach growled loudly, breaking her concentration.

Ojiisan laughed and went to the fire. As he began grilling fish, Hiro set the table, dishing out rice.

“There’s nothing like the taste of rice cooked over firewood,” he said. He poured miso soup into bowls and placed red lacquered wooden tray tables on the tatami mat floor.

When the fish was cooked, Ojiisan set a fourth tray in front of the altar.

“For Satoko’s spirit,” he said, glancing over at Jet with warmth in his expression.

They sat down to eat. Jet sipped the warm miso soup. The nameko mushrooms smelled like wood, spreading a smoky taste through her mouth.

“Your mom loved this kind of miso,” Ojiisan said. “As soon as fall came, she’d go hunting for nameko in the forest. She was a good hunter.”

“Really?” Jet looked up, surprised. She’d only seen her mom hunt for food in the grocery store.

Then he leaned forward, lowering his voice. “Around here, people like me are called matagi. We’re just hunters. If anyone asks you, that’s what you should say. Okay?”

Jet nodded, though she was alarmed. Weren’t they?

“The name of our town means ‘bear’ in the Ainu language,” Hiro said, his chest radiating pride.

“That’s right,” Ojiisan replied. “Many families once hunted bear to survive. To the Ainu, the bear was a gift from God. They respected this powerful creature. He gave them his meat, his fur, his medicine. They gave him their gratitude and respect.”

“And he kept the Wa away from the mountains. The Wa are afraid of bears. They’re afraid of Kanabe.” Hiro’s eyes sparkled. “And us!”

“Are the Wa a gang?” Jet asked, remembering what Hiro had said.

“Not exactly,” Masakichi said. “They’re the Emperor’s ancestors.”

“They captured our ancestors and made them slaves,” Hiro practically growled, making Aska’s ears suddenly stick up. He stroked her fur and she moaned, ears softening.

“They haven’t been around for a while, and we’re happy to have them stay away from our mountain as long as they want,” Ojiisan replied.

“Forever isn’t long enough!” Hiro said fiercely.

“What do they want?” Jet asked, looking over at her grandfather.

Ojiisan hesitated. “The Kuroi family were nomads whose ancestors, the ancient Izumo people, traveled around Japan selling bamboo crafts to survive. As they traveled, they built a kind of network, picking up information and carrying it from town to town.”

“And?” Jet asked. The hair on the back of her neck stood up.

Ojiisan sighed “In those days, that information was very rare and valuable. But in this day and age, there’s email and iphones and satellites and even clones of animals—things your old grandpa couldn’t have dreamed of fifty years ago. People can hear what we’re talking about right now, even though they’re thousands of miles away.”

“That’s true. But what does that have to do with us?” Jet asked nervously.

Ojiisan continued. “You see, our ancestors might have made some enemies. People didn’t like their secret ways, didn’t think there was a need for them anymore.”

“But you don’t think so, do you?” she replied. Her grandfather obviously liked the old ways. He still lived in a wooden house and cooked over a kindling fire. In fact, he seemed almost untouched by the twenty-first century.

Masakichi cleared his throat. His deep blue eyes sparkled as he looked into Jet’s eyes. She stayed perfectly still.

“As long as there’s a mountain, there will be a forest. As long as there is a forest, there will be bears and mushrooms and yakuso—medicinal herbs—and the village will survive. So we don’t have to worry…”

Hiro frowned. “Yeah, but only if we protect it.”

“How will you… we… protect it?” Jet asked quickly. There was so much she wanted to know.

Hiro looked over at Ojiisan, who laid down his chopsticks.

“You must be tired,” he said softly but firmly, closing the subject.

“You could say that.” She was almost too tired to keep her head up and eyes open. The train ride had been long. But still. Tension coursed through her body. She could see that Ojiisan didn’t want the old ways to die. And neither had her mother. After all, Satoko had made Jet come all the way to Japan. And they were clearly being threatened. But by whom? And why now?

Jet didn’t want to argue, to show Ojiisan her bad qualities. She would no longer be what her homeroom teacher had written in her progress report: “witty, sarcastic, at times cynical, and maybe a little antisocial.” She’d determined not to be that way in Japan.

Ojiisan looked softly at Jet, as if understanding all she could not say.

“We should all get some rest. It’s been a long day.”

“I’ll show Jet her room,” Hiro said, picking up Jet’s backpack and suitcase. Ojiisan quickly led them down a wooden hallway to a tatami mat room that opened onto a small stone garden. They brushed their teeth in a big metal sink. The toilet was a hole in the ground.

“The spare room is not very fancy, but we’ll put out a futon, and you’ll rest well. If you hear any strange noises, whistle like this.” Ojiisan made an owl’s call from deep in his throat. Jet was startled—it was the same sound her mother and J-Bird had taught her in the desert.

“There are a lot of wild animals, you know. But don’t worry, they’re friendly. Most of them, that is. The bears are used to us.”

Jet might have looked afraid, but she couldn’t help but yawn.

“You’ve had a long journey,” Ojiisan told her. “Come.”

Jet said goodnight to Hiro after he put her bags down on the tatami. He opened his mouth, as if he wanted to say something, but Ojiisan ushered him and Aska back down the hall.

“Sleep well. Good night!” he said, eyes shining as he kissed her on the forehead tenderly like a child.

After he’d left, she changed out of her clothes and into her nightgown, which still smelled like Southwestern desert earth. How strange to think that just 48 hours ago, she’d been in America. Now she was here, a world away. Jet let herself sink into the folds of the many blankets. She heard him shut the front door, then bolt it. He closed the window shutters, locking them, too. She couldn’t stop thinking about what Satoko had told her–that people would want to hurt her. She should have warned Ojiisan. Or did he already know? Hiro certainly knew something, Jet could feel it in her bones.

The thought of danger slowly faded. Jet had never felt safer. For so long it had been just Satoko, J-Bird, and herself. Now she had a grandfather and a cousin. Even a dog. She had the treasure she’d wanted for as long as she could remember—a family.

Was it too much to hope that she could keep it?