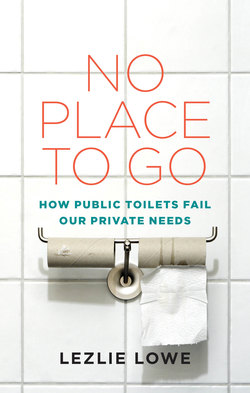

Читать книгу No Place To Go - Lezlie Lowe - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 GAME OF THRONES

ОглавлениеSpring 2005. I abandon my kids and trundle down the grimy concrete stairs to the public bathrooms in the bunker-like Pavilion on the Halifax Common. Practically every day – summer, fall, spring, and winter, doesn’t matter – I yank on the heavy door, more surprised when it budges than when it doesn’t. Getting in is only something of an advantage. These public bathrooms are smelly and soap-free. There’s no changing table, often no paper towels, and the hand dryers have been smashed off the walls. I turn around and climb the stairs to retrieve my girls. To use these city-run facilities, I leave my double stroller and the rest of my belongings outside, crossing my fingers that nothing gets stolen while I help a toddler down the stairs, balancing an infant and lugging a diaper bag.

I brave it. My bladder’s weak, always has been. It’s not a medical condition. It’s just that, when I have to go, I really have to go. What’s more, my feeble ability to hold it far exceeds my toilet-training three-year-old’s, so daily down the stairs I tromp to give that handle a yank. Most days, it’s no go, which means a quick turnaround to head home to pee or change someone’s pants. I’ll learn later that the softball league that uses the diamonds on weekends has copies of the keys; they turn the deadbolts when they leave on Sunday evenings, lest up-to-no-good mothers like me get in and mess up the place.

I’m on the Common because it’s close to my home: a convenient place to go to get the heck out of the house. Being free of four walls with young kids is a prophylactic against maternal madness, and the Halifax Common is a central park on downtown’s edge with plenty of grass and trees, and paths for strolling. The Common was set aside in 1749 as a community livestock pasture (the irony here is inescapable – this place was, at one time, a giant bathroom). Having banished sheep and cows, the modern Common’s twelve hectares hold tennis courts, ball diamonds, a skate park, a swimming pool, and a splash pad. The place is built for leisure. Unless, that is, you’re the kind of person who uses the bathroom.

Every time I’m out with my infant and toddler, I need to change a diaper or respond to the urinary urgency of my toileter-to-be. Often both. Every time. Parents reading this know it to be true. So it’s inconceivable – though here I am living it – that no municipal workers seem to check that the Common bathrooms are open, let alone clean and stocked. This is simply what passes for a public toilet in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 2005. And, look, that’s no slag on my home city. Halifax is a provincial capital and regional centre with six universities, active arts and sports scenes, and access to the unbounded wild within a thirty-minute drive of downtown. In short: we take quality of life seriously. This same kind of sad-excuse-for-a-public-toilet is what passes in cities and parks all over North America even today.

And this, precisely, is the problem.

It’s the reason I carry little girls’ underwear in my purse. It’s the reason I’ve developed toilet radar; the reason the first thing I look for in a new environment is the closest place to pee. It’s the reason I started to ask questions about public toilets. Like, why aren’t there more of them, in a developed country with enough money to fund polar and space exploration and to give generous tax breaks to multinational corporations? And how is it that, with kids, I started having so much trouble navigating a city that I used to steer through relatively problem-free? People tell you your life changes once you become a parent. And it’s true: I sure started seeing public bathrooms differently.

Or, you might say I started seeing them at all. And once I began to think about toilets, I couldn’t stop. The more I learned, the more it struck me that the history of public toilets in cities is the history of cities themselves. Toilets have been a central, recurring theme in my journalism practice ever since I wrote my very first piece as a staff writer for Halifax’s alternative weekly paper, the Coast (that’s when I found out the softball leagues were the ones locking me out). Public bathrooms are invariably one of the highlights (or lowlights) of my travels. My holiday pics are flooded with public-bathroom shots; I reach excitedly for my Twitter feed when I find a great bathroom sign, like the ones at Edinburgh’s Meadows park, which include distances along with way-finding. Public bathrooms, so seemingly mundane, keep me up at night. They spell out how unwillingly we share public space, how we would rather pretend we never defecate or urinate (or, for that matter, menstruate). Public bathrooms are private spaces that reveal public truths. I can’t help myself. I have to peek inside.

My bathroom fiascos on the Halifax Common aren’t just my stories; they are the province of parents all over. For most North American kids, the leap out of diapers happens around age three. Toilet training is a time of frayed nerves, when leaving the house goes high-stakes. Kids – non-parents may be unaware here – give little warning of impending sanitary disaster. It can be zero to puddle in under sixty. And in the miraculous case that a new underpantser is aware enough to give the gotta-go in time, a most pressing question indeed presents itself: where?

I call Andreae Callanan, a friend of a friend in St. John’s, Newfoundland. I want the perspective of a parent in a different city, and one with higher stakes. Callanan has four kids. She knows this game of thrones. ‘I can’t even think of how many times my children have had to pee in an alleyway or behind a bush, or a mailbox,’ she says. ‘You do these things because you have to.’ This isn’t dinner-party conversation. No parent wants to explain that his kid pooped on the playground slide, or describe how he cleaned it up with a McChicken container fished out of the trash. Callanan tells me she once changed a soiled diaper in an outhouse-sized café bathroom in Montreal, aiming a soggy child into a clean diaper balanced on her lap as the then-new mom sat on a toilet. The nanny of one of my friends is horrified at the lack of public bathrooms in parks in her adopted city of Ottawa. She’s taught her three-year-old charge to pee on the back of the electrical box at one of the parks. ‘I wasn’t sure if that was an attempt at privacy,’ my friend confides, ‘or a passive “fuck you” to the Parks and Rec department.’

Employing the electrical-box fix or not, parents and caregivers of children, especially those in the throes of toilet training, must develop an expertly tuned bathroom homing device. For Callanan, downtown St. John’s presents an Ancient Mariner–calibre conundrum – bathrooms, bathrooms everywhere, but not a place to pee. Think about it: every commercial building has a bathroom. Every café and store, and restaurant. Ditto for office towers and government buildings, which Callanan eyes directly. ‘These are companies with gazillions of dollars. They already have staff to keep the building clean, and they can’t have this little bit of generosity to open up two clean rooms? It just seems so stingy.’ It’s not that simple, of course. Provision costs. There’s add-on water and paper, and electricity. Extra cleaning. Perhaps more significantly, providing bathrooms means welcoming the world and being okay with it. There’s an element of people – unhoused people, drug dealers or drug users, those cruising for sex or looking for a place to nap – that businesses usually want to keep out, and that goes even if those folks only want to come in to actually use the bathroom. Keeping some out is most easily achieved by keeping everyone out.

Callanan goes to the park with her kids regularly from about March through December. But almost all St. John’s park bathrooms – there are about fourteen across the metropolitan area to serve 200,000 people – are open Victoria Day in May through Labour Day. After that, parks staffing is cut back because kids are in school, days are getting shorter, and temperatures are dipping. ‘We generally only have walkers then,’ says St. John’s deputy city manager Paul Mackey when I speak to him in the fall of 2014. ‘Not so much activity.’ So for Callanan (and presumably all those lonely walkers), it’s the bushes.

The St. John’s Parks and Open Spaces Master Plan was presented to city council in late 2014. The plan was the result of scads of public meetings, but the records of the consultation include no mention of bathrooms whatsoever. Mackey tells me toilets weren’t part of the discussion because that would have been going into too high a level of detail. But, he says, the city has heard an earful from walkers on the Grand Concourse portion of the Newfoundland T’Railway, who wonder where they’re supposed to find relief along the pathway’s nearly two hundred kilometres. The Grand Concourse was designed to encourage active transportation and links St. John’s with eight-and-counting bedroom communities. Mackey says it’s well-used. ‘In the winter, people are still walking.’ (Mackey himself may now have joined them; he retired in 2015.) Some others, like Callanan, are out playing in the snow with their kids. Contrary to the point of urban parks, sometimes she opts for the mall when she needs to get everybody out of the house. It’s a ‘much less stimulating but accessible environment,’ she says. She would rather spend her money downtown, but at times the burden of being on bathroom red alert is too tiring.

It’s easy to pretend public bathrooms don’t need any fixing when no one talks reasonably about their problems. Toilet talk boomerangs between clinical and bust-a-gut. We can spill to our doctors about our toilet habits. (Well, some of us, anyway.) We can toss out potty jokes. But we don’t have the language to deal with the everyday. Your kid had to squat behind a shrub and wipe with purse-bottom-mottled Kleenex? You shit your pants in line at Starbucks because you had to buy something to get a bathroom key? Or at Tim Hortons, because you’d been denied the key due to some prior misdeeds. (For context on this one, search Google videos for some combination of ‘Tim Hortons,’ ‘British Columbia,’ and ‘angry pooper.’ Actually, you know what? Don’t.) La-la-la… I can’t hear you… Meanwhile, targeted ads follow us around the internet pushing plush toilet paper and wet wipes. The glossy design mags I browse at my local magazine store paint clean scenes of fluffy towels and svelte toilets looking more like hat boxes than your average commode. It’s not difficult to see where the bathroom-sexiness line is drawn. Toilet advertising is all about improving the private bathroom experience selling luxury, cost-saving eco-friendliness, or hypercool design. It’s not about bettering public conveniences and simple access. After all, what’s there to sell in a public bathroom? There’s no commerce in social justice and public health.

Plus, on a global scale, we’ve got it good. Here’s a truth bomb, care of the World Health Organization (who) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): 2.3 billion people live without basic sanitation – roughly equivalent to the populations of Africa, North America, and Southeast Asia combined. That count is from the 2017 sustainable development goals Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. And, while the report acknowledges that things are getting better, the goal of universal basic sanitation by 2030 will not be met at the current rate of improvement.

One solution, such as it is, for lack of basic sanitation is open defecation, which I’m sorry to say is exactly what you’re likely picturing – people shitting in fields and on streets. Open defecation is a daily reality for 892 million people, most of them in Central and Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Inadequate sanitation and open defecation spread disease – intestinal worms, schistosomiasis, and trachoma, for starters – and causes diarrhea, which is directly responsible for the deaths of 280,000 people a year, according to the who and UNICEF. Add in the related woes of inadequate water and hygiene, and the number of annual deaths shoots to 842,000. Almost half are children under five.

Take a second to sit with that. Almost half the deaths are of infants and toddlers. When a child in Halifax gets diarrhea, she goes to bed, rests up, and maybe munches some pediatric electrolyte freeze-pops. In too many nations, diarrhea, added to a lack of easy access to clean drinking water, soap, and a place for handwashing, mows down 361,000 little kids a year, plus another 480,000-odd adults. These are staggering numbers, and ones, perhaps, easy to dismiss as you fill a water bottle at your kitchen sink. But know this: open defecation happens in major North American cities, too. When homeless people look too shabby to be welcome in cafés and malls, when they’re unsheltered and sleeping rough, when they don’t have a free on-street bathroom to visit, or enough spare change to pump into one of the automatic public toilets (APTS) spouting like mushrooms in some North American cities, they have to go somewhere. The average person goes to the bathroom six to eight times a day. You do the math.

Spring 2014. The never-open Pavilion public bathrooms of my kids’ childhoods are now caged with chain-link and permanently padlocked. Those dank concrete stairs I used to clunk down now collect desiccated leaves and McDonald’s coffee cups. The city will open them for special events if organizers put in a request, but I can’t fathom they’re used much. Halifax’s supervisor of contract services, John Cook, takes me in to show me around. The bathrooms are ghostly and dark, and notably cleaner than I’ve ever seen them. The chipped plywood stalls have been replaced with plastic laminate separators, the broken mirrors removed. Still, no strollers or wheelchairs can get in, and even for the able-bodied who can get down the stairs, there’s something eerie about this windowless, subterranean space. It feels, from the perspective of a woman, too easy to be trapped, too difficult to be heard. Most people probably make the two-minute walk to the new public washrooms on the other side of the Common, even when these are open.

The new bathrooms were built in 2007 in response to the community clamouring for better provision. Business owners were fed up with people asking to use their customer washrooms because the Pavilion toilets were dirty, scary, or locked. A nearby Royal Canadian Legion reported to the city that, on average, three hundred people a day were coming through the door to relieve themselves. The new Common bathrooms are large, accessible, and, crucially, more vandalism-proof than those of the Pavilion, which was racking up somewhere in the range of $30,000 for annual fix-ups, graffiti removal, and repainting. But vandal-proofing comes at a different cost. At the new Common bathrooms, there are no mirrors at the sinks and no paper towels. The taps, flushers, and hand dryers are automatic. This provokes uneasy, perhaps unanswerable, questions: What makes a good public bathroom? Can durability go too far? I appreciate the new Common bathrooms, I do. But, jeez, there aren’t even toilet seats. You just perch on a cold stainless-steel rim.

I get it – unbreakability is a virtue. These are public bucks and taxpayers are tight-fisted hands at the grindstone. But the new Common bathrooms don’t necessarily address user needs. They’re open only 8 a.m. to 10 p.m., which sticks early-morning exercisers or anyone walking across the Common late at night (it’s a popular route from downtown bars to Halifax’s west-end and university neighbourhoods) back in the bushes. Plus, when the city built this brick shithouse, it didn’t winterize it. The bathrooms are closed November 1 through May 1, recalling downtown St. John’s – though there, according to Paul Mackey, most of the bathrooms are winterized; it’s just that there’s little winter demand. In Halifax, it’s a perplexingly opposite situation – great demand and no ability to open the bathrooms. The Halifax Common has become a winter hot spot since the addition of a four-hundred-metre speed-skating oval in 2010. The oval sees more than 120,000 skaters through December, January, February, and March. Within a year of its opening, the city installed a brick plaza, a special events stage, a warming trailer, and a massive piece of public art. As far as bathrooms? The city brought in a row of porta-potties. There are no signs on the Common, or the surrounding area, to light the way for toilet seekers. Unless you know where you’re going, you’re not going at all. Stand in the middle of the Common and punch ‘public washroom’ into Google Maps and all you get is a single hit: a bathroom on the waterfront that’s a twenty-one-minute walk away.

The ramifications here seem clear, not least for tourism. Holidaymakers who don’t have to rush back to their hotels are more likely to stay out and spend money. In most respects, Halifax is pretty savvy when it comes to catering to its 5.3 million annual overnight visitors. And why wouldn’t it be attentive to an industry that, in 2017, pumped $1 billion into the city’s economy? Yet showing the way to the city’s paltry flushable resources isn’t a priority for Halifax’s tourism marketing agency, Destination Halifax, because, apparently, no one ever mentions it to them. When I began researching this book in 2014, I was told they’d never had a single complaint about the dearth of signs (or public toilets). ‘It sounds like one of those things,’ then city spokesperson Shaune MacKinlay told me, ‘that nobody has given a lot of thought to.’ You don’t say?

Perhaps the issue deserves an ear. A string of small communities in the British Columbia interior began focusing on public bathroom installation in 2017 as a way to boost tourism; ditto Denver, Colorado, which introduced two mobile public facilities the same year. If Nova Scotia hopes to hit its goal of $4 billion in annual tourism revenue by 2024, led by its capital city, it will likely be flush in more ways than one.

Speaking of tourism, Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, makes a perfect day trip from Halifax. It’s also a good little town to have a pee in. The UNESCO World Heritage Site was founded in 1753 and today is peppered with colourful wood-shingled houses and shops, and prominent kiosk signs listing the town’s main attractions, like the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic, the rebuilt schooner Bluenose II, and the town’s kick-ass stand-alone public bathroom. ‘We are a community that actively seeks tourist traffic,’ says Mayor Rachel Bailey. ‘A washroom is kind of a necessity.’ And that was the very moment I fell in love with Mayor Bailey.

The Lunenburg public bathroom opened in 2001 and was designed to emulate a Lunenburg cape-style home from the 1700s. It’s the only stand-alone public washroom in town, but Lunenburg is small (2016 population: 2,263) – it’s the kind of place where a real, live human answers when you ring the main municipal line – and the bathroom is easy to get to even from the farthest reaches of the town centre. Mayor Bailey nevertheless suggests Lunenburg could do better, commenting that the north and east ends of town are not as well served as the bathroom-boasting west. Bailey is unswayed when I point out how short that distance is – even a hyperbolist couldn’t estimate the distance across Lunenburg’s downtown as more than a kilometre. ‘I know when you have little ones,’ she says, ‘you don’t always have a lot of time to make it.’ (Preach, Mayor Bailey, preach!) There’s long been talk of adding a second permanent public washroom, and the town’s waterfront development agency is working on plans for bathroom and shower facilities at the other end of the boardwalk. In the meantime, Lunenburg has porta-potties in areas where there are more people and more need, and the town is actively working to make its existing bathrooms accessible to the public, like the one at town hall, which is not accessible, but clean, well-stocked, and very well signed.

The design of the little clapboard Lunenburg public washroom is not the stuff of afterthought. It’s on a main street – Bailey: ‘That’s where the people are’ – and fits puzzle-like into the town’s architecture. Outside the building are a bench, a stone terrace, and, in season, an abundance of columbines and hostas. The interior boasts painted tiles created by one hundred elementary school students who walked the streets of their town choosing flowers, houses, sailboats, and cats to render for the bathroom, each tile its own scene. The bathroom art has been made into a series of cards sold by the Lunenburg Heritage Society. Bea Renton, Lunenburg’s chief administrative officer, tells me she gets emails from tourists in praise of the toilets.

Lunenburgers paid just over $100,000 to build their bathroom and they shell out a little over $14,000 a year to operate and maintain it during its open season, from mid-May through Halloween. It used to close in mid-October, but council voted to extend the dates based on requests from residents and will keep it open later depending on the weather and the need. Opening it all winter is an option, Bailey says, based on demand. The town can also take in revenue from the bathroom by renting space in the front lobby.

I caught wind of the Lunenburg toilet from a friend who stumbled upon it and emailed me a report: ‘Lunenburg has an outstanding public washroom,’ she told me. ‘In a cool building near the waterfront.’ She noted it was spacious and clean and blended into its surroundings. My friends know me well (as does my husband, who snaps pics of ‘Customers Only’ bathroom signs and texts them to me, anticipating my outrage). They’re used to my reporting, both social and professional, and my non-stop touring of the public bathrooms I encounter, whatever city I happen to be in. Like I said, I can’t help myself. The public toilet is a peephole into our public and private selves.

Barbara Penner is a senior lecturer in architectural history at London’s Bartlett School of Architecture and the author of 2014’s Bathroom. In these seemingly mundane spaces, Penner says, ‘you quite quickly understand what society thinks is important.’ Those who are closest to me – and even those who aren’t – invariably laugh at my abiding obsession with public bathrooms. That’s fine with me. And with Penner. ‘People’s initial response is often, “Hee hee hee,’’’ she tells me over Skype from her London office, ‘but followed quite often by very personal confessions.’ After all, we all have a personal relationship with public toilets. They are as inescapable as our desire to leave our homes, as unavoidable as the human need to urinate and defecate. As author Rose George writes in The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters, ‘To be uninterested in the public toilet is to be uninterested in life.’ So? What are we waiting for? Let’s go.