Читать книгу The Holy Earth - Liberty Hyde Bailey - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword by Wendell Berry

Fifty or so years ago, when I was beginning my effort to learn to write about agriculture, I obviously needed to learn something of what already had been written. My searches through the card catalogue and the stacks of a university library revealed that a good deal more had been written than I was ever going to read, though I skimmed and dabbled no doubt to some improvement of my mind. What I remember most was the frequency with which I came upon books by Liberty Hyde Bailey, who alone was the author of a fairly adequate agricultural library. Until then I was unacquainted even with his name, and I would be a long time learning much about him. But finding his books, leafing through them, skimming and dabbling as I was doing then, I formed an impression of him that has been confirmed by all that I have learned about him.

He was a scientist, credentialed and accomplished, with a scientist’s obvious need to speak with authority. That of course required some specialization, and he attained enough distinction “in his field” to become dean of agriculture at Cornell from 1903–1913. But his vocation clearly was not so much to a specialty or field as to country life in all of its aspects: farming, gardening, horticulture, forestry, nature and “nature-study,” animal husbandry, flower gardening, the economy and politics and culture of rural communities. You will know so much just from the titles of the books he wrote and edited. Beyond that, from the variety and number of his subjects you will suspect what seems to have been the truth: that, more than by science or even vocation, he was moved by a large and unresting enthusiasm, a liking and love, for everything having to do with the life of the countryside, human and non-human.

Liberty Hyde Bailey was born on a frontier farm in South Haven, Michigan, in 1858. He remained actively at work almost until his death, at the age of ninety-six, in 1954. The dates are agriculturally significant. He was old enough to remember his father’s purchase of a mowing machine as mechanization entered farming after the Civil War, and he lived to see the beginnings of the all-out industrialization of agriculture that followed World War II and still continues.

The vocational interests of Bailey’s life, agriculture and what he would come to call “nature-study,” were well established in his childhood. His interest in nature made him a botanist. His interest in farming made him a horticulturist. But as an observant child in a farm family, he also knew from early experience that the farm and the farmer shared the same fate. In the time of Bailey’s childhood, according to his biographer, Philip Dorf, the farmer “bought at retail” and “sold at wholesale” — a disadvantage that has remained constant and critical in the history of our agriculture until now. After the Civil War, also, the railroads grew in political power and public favor. Distance and the romance of cities became prominent in people’s minds. Farmers began to be disparaged about then, Dorf reminds us, as “rubes” or “hayseeds.”1 Perhaps for such reasons, as well as his native loyalties, Bailey’s thought and work were always directed to the worth, the prosperity, and the satisfaction of good farmers. To understand him it is necessary to keep always in mind, as he did, his three devotions: to nature, to the farm, and to the farmer.

The farm household depended upon nature; the prosperity of the farm household depended upon the farmer’s ability and willingness to keep the farm in a right relation to nature:

Most of our difficulty with the earth lies in the effort to do what perhaps ought not to be done.… A good part of agriculture is to learn how to adapt one’s work to nature, to fit the crop-scheme to the climate and to the soil… (9, this text)

This principle of adapting the farming to the farm or to the nature of the place is, or it ought to be, evolutionary and ecological enough for 2015 A.D., but Virgil said the same thing in 29 B.C. The current assumption that farming is an autonomous process safely indifferent to the uniqueness of places, let alone to an adapted “crop scheme,” is industrial, not agricultural.

The idea of the farmer as a figure of primary importance in connecting the human economy to nature stayed with Bailey all his life. The agricultural scientists of our own day find it easy to think of themselves either as scientists primarily or as developers of products for agribusiness. But to Bailey, as dean of the new College of Agriculture at Cornell, agricultural science was oriented to the land and directed to the needs of farmers:

This College of Agriculture was not established to serve or to magnify Cornell University.… If there is any man standing on the land, unattached, uncontrolled, who feels that he has a disadvantage and a problem, this College of Agriculture stands for that man.2

To Bailey, moreover, farmers were never merely producers of “farm products.” Nor, mercifully, did he ever imagine that they might become, as now, specialized producers of one or two products. In his view of them, farmers were people who lived on and from, and were directly sustained by, diverse and reasonably self-sufficient family farms. He assumes always the value of the farm family’s subsistence or household economy. He was spared the eventual scandal of “family farms” dependent on town jobs.

As an agricultural scientist committed to the improvement of farming and the education of farm people, he was concerned as a matter of course with the movement of the country people into the cities. He felt that this was to some extent inevitable, as a surplus of rural people sought work in factories and offices. “What bothered him,” says Dorf, “was that the exodus was draining off many of the best and brightest of the country boys and girls, the natural leaders of coming generations.”3 Bailey’s thought (still a good one, if tried) was to remedy the perceived dreariness of farm life by programs of “nature study,” which were meant to awaken children’s natural interest in the creatures of the natural world. The idea was to avoid the courses and sciences of natural history, and instead to take the children outdoors into the actual presence of the trees and fields, the birds and animals and wildflowers that they dependably would like better than books and facts. Nature study, Bailey said, “is an attitude, a point of view.… Its purposes are best expressed in the one word ‘sympathy.’”4 He obviously was hoping, first, that the pleasures of nature study would brighten the lives of country people, and second, that as the children of farmers grew up to become farmers themselves the sympathy derived from nature study would grow into sympathy for the land they farmed.

And here we must pause to consider how intimately Bailey’s word “sympathy” places us within our actual lives within our actual world, and how far it displaces us from the industrial world in which creatures are treated as machines and “farming” is reduced to the manipulation of machinery and chemicals.

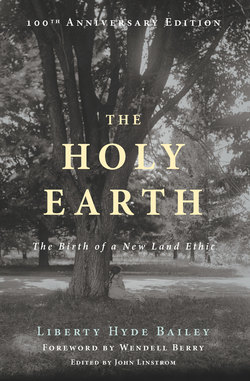

As we look back from our time to his, Liberty Hyde Bailey may seem in a number of ways a surprising man. If we have understood that he was a modern scientist, a follower of Darwin from boyhood, who even so would invoke sympathy as the aim of nature study, then maybe we won’t be too much surprised to find that he also would write, a hundred years ago, a little book entitled The Holy Earth. People who predictably find Bailey’s adjective dated or outdated or shocking in the context of science may be at least somewhat appeased by his candor. He called the earth “holy” in perfect good faith. And he did so in deliberate contradiction to its mere materiality, believing that “there is no danger of crass materialism if we recognize the original materials as divine and if we understand our proper relation to the creation, for then will gross selfishness in the use of them be removed” (4). Moreover: “One does not act rightly toward one’s fellows if one does not know how to act rightly toward the earth” (4). He was seeing the complex and profound ethical difference, sufficiently evident then and now obvious, between perception of the earth as divine and the industrial perception of it as a source of raw materials to be extracted, processed, and consumed. Futile as it certainly was in 1915, Bailey seems to have stood that world “holy” upon the earth to mark it off-limits to the kind of mind — then, as we know, arriving in force — that is “objectively” materialist and utilitarian.

In his values, affections, loyalties, and pleasures, Bailey was a remarkably complete human being, and that completeness is denoted by the completeness of his language. Reading this book, one necessarily becomes aware of a drastic change in our language over the last hundred years: how scrupulously it has been lopped and impoverished to suit the biases of materialism or realism. In his chapter titles alone, Bailey offers freely and familiarly a vocabulary long excluded by the filters of objective truth: not just “holy” but also “good,” “kindly,” “brotherhood,” “neighbor,” “beautiful,” and “soul.” Those words, and such words, do not refer to substances or quantities verifiable by measure, but to qualities that reveal themselves as true only after we have assented to them. But they are not for that reason forceless or without effect. By this vocabulary of qualities we recognize and protect the things of measureless worth upon which our life, and all life, depends. This we can now see from the measurable failure of the industrial use of nature, which is opposed to all the qualities by which nature would be sustained in human use.

And so to Bailey, “holy” is a word of force by which to move “our dominion” from “the realm of trade” into “the realm of morals” (12). The word “dominion,” he takes of course from the first chapter of Genesis. The alleged conflict between Genesis and evolution he leaves to the literalists of religion and science. The question of our dominance he assumes is settled: We are now and have long been dominant. The question of interest is how, being dominant, we will conduct ourselves. If, taking Genesis seriously, we see the earth as holy, then reverence and humility ought to prompt us to use it conservingly and kindly: “If the earth is holy, then the things that grow out of the earth are also holy. They do not belong to man to do with them as he will” (13). This invokes a chastening moral fear, actual and ancient, that we have reduced to a “problem” merely technological and political. The damning fact is that “our dominion has been mostly destructive” (17), and this book was written to remind us that the proper keeping and good care of the earth is our highest and most solemn duty.

If Bailey’s language, in what I have called its completeness, is deliberately poised against the disheartening language of materialism, well begun in his time, it is also by its nature poised against our own time’s “ecocentric” misanthropy and its ugly neologisms. In the terms of this book, humans are by no means excused from their long history of irresponsibility and destruction, but they are nowhere seen as “anthropocentric” interlopers. To see the earth as holy, and therefore as demanding the most conserving arts and sciences of husbandry, is to put humans where they belong: central of course, like all creatures, to their own consciousness of their own needs, but also subordinate to, called to adapt their work to, the ordering of things in which the earth is the primary good.

For me, and I’m sure for others who share my reasons, there is a happiness and a kind of reassurance in Bailey’s unworried use of the language of conserving qualities. But there are also problems with his language, and these have got to be dealt with. Dealing with them requires some trouble, but it is also rewarding, for they bring us directly into the presence of our history. The problems all arise from the differences made by the hundred years between the first publication of The Holy Earth in 1915 and this new edition of 2015. Perhaps we should not say that no century ever has more changed the world, but we can say with some confidence that no century ever has changed it more drastically, or, from our own point of view, done it more damage.

In 1915, World War I still had three years in which to reveal its horrors. Bailey could to some extent anticipate the catastrophe that lay ahead, both military and industrial — his foreboding moved him to write this book — but he could not yet have known its limitless violence. He was still free of actual knowledge of the actual destructions that by the time of his death in 1954 had already made the twentieth century the most destructive of any so far. And so he could write with a confidence that could not come so easily now:

We … know that the final control of human welfare will not be governmental or military, and we shall some day learn that it will not be economic as we now prevailingly use the word.…We shall know the creator in the creation. We shall derive more of our solaces from the creation and in the consciousness of our right relations to it. We shall be more fully aware that righteousness inheres in honest occupation. (84)

Legitimate human hope could not be better stated than this. It is good prophecy as Isaiah is good prophecy — for Bailey’s time, our time, and all time — but it bespeaks a fulfillment easier to foresee then than now.

When in 1942 he wrote a “Retrospect,” a sort of foreword, for a new edition, he continued his old prophecy, in much the same tone:

When the epoch of mere exploitation of the earth shall have worn itself out, we shall realize the heritage that remains and enter new realms of satisfaction. (xxvii)

Today we long for this with the same longing, but now we must ask if this epoch will not wear itself out by wearing out the earth. And 1942 was only the first year of America’s engagement in World War II. In 1942 Bailey had not known that war in the full progress of its brutality and violence. By the time he died in 1954 he would have known of the Holocaust, the firebombing of cities, the coming of the science of nuclear terror, the beginning of the Cold War and the first of its spawn of “small” hot wars. He could not have begun to imagine the extent of the progress of industrial warfare against humans and against the earth between 1954 and now.

And so, though we read The Holy Earth in our time as an act of acknowledgement and appreciation of one of the best in the lineage of conservationists, our reading becomes also an act sometimes of a kind of translation. History, to begin with, has simply overturned some of his most cherished articles of faith. He believed — or wanted to believe, as who would not? — that the natural world or “background” was more durable, less vulnerable to human harm, than it has proved to be. In 1915 he could write, though already whistling in the dark, “The fields do not perish…” (107). But we know, by measures objective enough, that they do. Though most of us still prefer not to know, the fields are now perishing, every day and all over the world, from erosion, poisoning, “development,” and neglect. Bailey wrote that “the sea remains beyond [our] power to modify, to handle, and to control” (109). But now, by pollution and other forms of violence, we certainly have “modified” the sea, the seas, the oceans, and all the waters of the world. So modified, they may be less controllable than ever, and all because of our inability to control ourselves.

As a result, many of us now cannot so easily speak of the human “conquest of the earth” and our “contest with the planet” (57) as Bailey did in the chapter entitled “The Struggle for Existence: War.” Mainly the problem here is that the language is out of fashion. Bailey was too well experienced and knowing to doubt that we must, to an extent, struggle for existence, and that we are, to an extent, in a contest with the planet or with nature. That struggle and that contest can be denied only by people with sedentary jobs who don’t work outdoors in the wintertime. But Bailey’s chapter is a brief against war, and he specifically denies any equation between the struggle for existence and war, or any attempt to justify or excuse war as “natural.” And his terms “conquest” and “contest” are sternly qualified by two statements radically pertinent to our predicament now. The first is evolutionary: “the final test of fitness in nature is adaptation, not power” (56). The second is traditional wisdom, far older and more necessary than any precept of science:

The final conquest of a man is of himself, and he shall then be greater than when he takes a city. The final conquest of a society is of itself, and it shall then be greater than when it conquers its neighboring society. (56–7)

But when he goes on to say, “We have passed witchcraft, religious persecution, the inquisition, subjugation of women, the enslavement of our fellows except alone enslavement in war,” we can only reply, “Don’t we wish!”

In some places this book can easily be misunderstood just because certain words don’t mean to us now what they meant a hundred years ago. If our eyes widen on first encountering Bailey’s phrase “the holiness of industry” (79), that is our mistake, not his. By “industry” he meant the virtue of industriousness, the ability and willingness to work — not, as to us, an economic and technological system of violent production and wasteful consumption.

When he speaks, on page 89, of the need to preserve “individualism,” he is not referring to the supposed right of separate persons to do as they please, or of the strong to triumph over the weak, but rather to the proper respect for individuality that would “protect the person from being submerged in the system” (87). He associates “individual” with “independent,” “original,” “responsible,” and “free.”

And when he says, on page 97, that “The life of every one of us is relative,” what he has in mind is nothing akin to the idea of relativism. He means that we are related or connected to what, in this part of the book, he calls “the backgrounds,” or “the background spaces.” I think these latter terms are regrettable. He seems to be reaching toward “ecosystem” and “ecosphere,” neither of which was then in use. But he could have said “nature” or “the natural world,” and I wish he had. “Background” suggests a stage setting, as our own degraded word “environment” suggests surroundings. We are fortunate now to have the term “ecosystem” in common use, for it denotes a household of which the indwelling creatures, living and non-living, are mutually the parts.

But these and other such differences, though they require some vigilance and care in reading, do not mean that this book is irrelevant or obsolete, as industrialists and certain ologists would like to think. We need Bailey now as a teacher and ally because the problem of land use, which is to say land abuse, is a constant from his time to ours, and is worse in ours than in his. He wrote this book because he saw the need to “act rightly toward the earth” (4), and the need for such right acting is more urgent now than a hundred years ago.

As a countryman by birth, upbringing, and predilection, Bailey was ceaselessly aware that the results of our use of the earth, whether abusive and extractive or responsible and conserving, are inescapably practical. Nobody in the lineage of conservationists so far has been so attentive, not just to the need to care for the earth, but to the arts, the sciences, and the pleasures of doing so. He knew, as most conservationists do not yet know, that everything depends on the character, the culture, the motives, and the skills of the people of the land economies who use the earth and, by using it, connect the whole society to it.

He knew also that there is no practical difference between the land user who does not know how to act rightly toward the earth, and the land user who cannot afford, or who does not have the time, to do so. Another constant from his time to ours has been the inferior economic and social status of the farmer. Through all the centuries of war, he wrote,

there have been men on the land wishing to see the light, trying to make mankind hear, hoping but never realizing…. They have been on the bottom, upholding the whole superstructure and pressed into the earth by the weight of it. When the final history is written, the lot of the man on the land will be the saddest chapter. (91–2)

Bailey was as mindful of “the planet” as we are, but to save it he would have liked to see it equitably and democratically divided so as “to give the husbandman full opportunity and full justice” (92). He believed in 1915 that the establishment of governmental departments of agriculture and the land grant universities would lead to such opportunity and justice, helping to achieve “a satisfying husbandry that will maintain itself century by century, without loss and without the ransacking of the ends of the earth for fertilizer materials…” (22). From our perspective in 2015, this is another forlorn optimism.

But a vision is not necessarily invalidated by failure. Bailey’s vision, by no means his alone, was wrong for industrialism but right for agriculture. It was right in general, and in plentiful detail, validated by a long history of good and bad examples — and validated in our time by the now-manifest failure of the industrial juggernaut of the years following World War II. He has a high and honorable place in the lineage of teachers — Thomas Jefferson, F. H. King, J. Russell Smith, Sir Albert Howard, Stan Rowe, Wes Jackson — who, if we ever finally decide to act rightly toward the earth, will light our way.

We need him for his practicality, but also for the pleasure of his company. He was unapologetically a countryman. He would never have described himself deprecatingly as “just an old country boy.” He liked country life in all its aspects, and everything he had to say about it is informed and seasoned by affection. His prose is robust, energetic, direct, and economical, with sometimes a surprising exactitude that would have delighted Marianne Moore:

This kind of apple is very perfect in spherical form, deeply cut at the stem, well ridged at the shallow crater, beautifully splashed and streaked with carmine-red on a yellowish green under-color, finely flecked with dots, slightly russet on the shaded side, apparently a good keeper; its texture is fine-grained and uniform, flavor mildly subacid, the quality good to very good… (69)

We feel, as Robert Frost said we should, what a hell of a good time Bailey had in writing that.

The point, to him, was not only that a beautiful thing gives pleasure, but also that the beauty and the pleasure were ordinary, within reach of anybody — democratic, as he might have said. The apple was “a thing of exquisite beauty,” but its beauty was not rare or expensive. It was a common amenity of the kind that made a farmer’s life worth living, and a proper appreciation of it raised farming to a place of honor among the kinds of human work:

It is no doubt a mark of a well-tempered mind that it can understand the significance of the forms in fruits and plants and animals and apply it in the work of the day. (70)

..............................................................

I think it should be a fundamental purpose in our educational plans to acquaint the people with the common resources of the region, and particularly with those materials on which we subsist. (73)

..............................................................

It is worth while to have an intellectual interest in a fruit-tree. (73)

..............................................................

Fowls, pigs, sheep on their pastures, cows, mules, all perfect of their kind, all sensitive, all of them marvellous in their forms and powers, — verily these are good to know. (73)

He thus gives to our cant phrase “quality of life” a gravity and a happiness that most of us have forgot even to try for, exceeding the capacity of our language of novelty and the news, but reachable if ever again we should decide to try.

WENDELL BERRY

Port Royal, Kentucky, 2015