Читать книгу Me and Fat Glenda - Lila Perl - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Well, I won’t even tell you about the ride across the U.S. in the PINE RIDGE TOWNSHIP garbage truck except to say that it took six weeks and people kept giving us odder and odder looks the farther we got from California.

The reason it took six weeks wasn’t only because a garbage truck is about as fast-moving as a sea turtle in the Arabian desert, or because we had to use a lot of back roads because of different state turnpike regulations. It also took six weeks because we kept hopping from the house of one friend or relative of Drew or Inez to another.

And each place we stayed we spent a couple of days getting cleaned up, rinsing out our jeans and leotards and waiting for them to dry, and most of all waiting for the vibrations in our bone marrow to stop. Then back in the truck we’d climb and the whole thing would start all over again.

You have to understand that Drew had a lot of friends who seemed to be sprinkled across the United States like stepping stones across a river. And whenever there was a little too much space between the stones for a convenient jump, there was always a relative of Inez to fill in the gap.

This was easy because Mom is one of the most mixed-blooded persons you’re ever likely to meet. She’s part Irish, part German, part French-Canadian, and part American Indian—just for a start. The first night out from home we stayed with one of her third cousins on an Indian reservation in Arizona. We also made stops with Mom’s relations in Nebraska and Wisconsin and we even looped up into Canada to see some of the French great-aunts and uncles. But the one place we didn’t go was Crestview, Ohio.

“It’s completely out of the way,” Inez declared when I suggested it and Drew said why didn’t we at least give it a “maybe.”

“No,” Inez said with finality. “We’ll never get to New York at this rate.”

Well, if I ever showed you a diagram of our route from California to New York, you’d think a giant serpent had been wriggling its way across the U. S. Out of our way? What way? A bunch of crazy curlicues that inched along in the general direction known as east.

So I never did get to see Aunt Minna again. Pop tried to be consoling, especially when I cried a lot in Pittsburgh after I got hold of the road map and found out we were only about an inch and a quarter away from Crestview, Ohio.

Even with all the people we kept stopping off to see, and lots of them with kids my age, the trip was awfully lonely. Then, too, all of my friends from California were left behind, probably forever, and I didn’t know if I would find any new ones when we got to New York.

Most of all I missed Toby. Every time I ate a hamburger I thought of him, and you can imagine how often that was, since I practically lived on hamburgers the whole time. Toby and I had stopped our alphabet-burgers at the letter K (kraut-burgers), and I knew I just wouldn’t have the heart to go on with the alphabet-burgers without him.

So, all in all, I was just as glad the day we rolled into Mill River, Long Island, New York, where the college was. All the buildings—if you can imagine this—were built in California Spanish-mission style and painted banana-yellow!

Inez took one look at them and laughed so hard she thought her leotards would split. “That architecture makes about as much sense as calling this place Mill River. It hasn’t got a mill anywhere in sight, and there isn’t a river within leagues of the place. Bays and oceans and sounds all around, but no river.”

Well, we looked pretty silly, too. The truck was by now the color of U. S. road dust that had been patty-caked by rain into an all-over coating of mud (which was a blessing because it covered the lettering on the sides). The college guard wouldn’t let us on the campus and made us drive around to the service entrance when Drew wanted to report to the administration office and find out about our housing.

Pop was gone a pretty long time, and when he came back he didn’t say a word, just climbed into the truck and started shifting gears.

“Where is it?” I asked, looking around at the wide gravel drives and big empty lawns that surrounded the three-story banana buildings. “Is it near?” There were still three weeks to go before the college opened for fall classs and the place was almost deserted.

“I just hope it’s spacious and roomy,” Inez remarked. “I don’t care if it doesn’t have a stick of furniture in it. As long as it’s not one of those little boxes divided into compartments like an egg crate. Most of the houses I’ve seen here in the East looked pretty discouraging.”

Pop muttered something, and Mom said, “What?”

“I said,” Drew repeated rather louder than was necessary, “you won’t like it.”

Inez got that wide-eyed expression that usually meant trouble.

We were still within sight of the campus, driving past a long, low two-story building that looked like an army barracks, when Drew began slowing down. Pretty soon he stopped altogether. From the way he was squinting through the window of the truck cab, you could tell he was trying to make out an address.

“Se-ven-tee four. That’s it.”

“No!” Inez exploded after a short pause. “I won’t. I won’t live in a box. I’ll live in a truck. I’ll live in a field. I’ll even live in a tent. But I won’t live in a box!”

“It’s not a box,” Drew said quietly. “It’s a ‘garden apartment.’ We’ve got the one on the upper-floor. Five rooms. A lot of the college faculty who are on short-term contracts live here.”

“Not me.”

“It’s only for a year.”

“Never.”

“It gets cold in the winter in New York, I. This place has steam heat.”

“No.”

“It has a completely remodeled modern kitchen, with a wall oven.”

“What do I care? We don’t need a kitchen. We eat raw food. Remember?”

“I don’t,” I reminded Inez.

“Well, you should,” she snapped. “It’s healthier.”

“Let’s just look at it anyway,” Pop suggested. “Yes, let’s,” I urged. It was a steamy-hot day and I was dying for a shower. Any place with a wall oven was sure to have a bathroom—and those were necessary. But Inez never seemed to think about things like that.

Besides, a few people had passed by and had looked up at the truck with curiosity. One lady was peering down at us from an upstairs window in the apartment next to ours, and another woman who was weeding a flower bed on the Kleenex-sized lawn in front of her apartment kept looking up at us through a clump of dangling weeds.

“All right,” Inez said at last. “I’ll look but I won’t like—and I won’t stay. They definitely wrote you they would provide housing. This is not a house. It’s not even a box.”

“That’s true,” Drew said. “It’s not a house. It’s housing. There’s a difference. You should have looked that up, I, while we were still back in California, before you went jumping to conclusions.”

“I won’t unpack,” Inez said after she’d made a quick tour of the five rooms furnished with colonial-style furniture that probably would have looked better somewhere else. (In a colonial-style house, I guess.) The rooms weren’t really so little, though, and I myself thought the place could have been fixed up to be rather cozy for a normal family. But we Mayberrys weren’t a normal family, so that put an end to that.

Drew kept staring out the rear windows of the apartment.

“That does it,” he said after awhile. “We won’t unpack.”

“Oh, I’m glad to hear you say that,” Inez exclaimed.

Drew kept right on staring out the window and shaking his head in disbelief and disappointment. “I thought there’d be a big expanse of ground back there, a place where a person could do a little construction. There’s nothing. Just a roadway directly behind the buildings and then a string of garages.”

“We’ll camp,” Inez said excitedly. “We won’t unpack. We’ll just camp, right here in the—ugh—apartment. And we’ll go scouting every day. There must be real towns around here somewhere, with real houses in them. I thought I spotted a few rustic-looking places after we left the Expressway this morning. There are three weeks to go before classes begin and before school starts for Sara. I’m sure we’ll find some place to live.”

And there was Mom consoling Pop as though he’d been the one to practically throw a temper tantrum at the start. Of course all this talk about to-unpack-or-not-to-unpack was silly. The apartment was already pretty full of furniture and there was no attic or basement or backyard shed, so how could we unload looms and zithers and iron spikes from the Union Pacific Railroad? We just brought in our clothes and got ready to spend a couple of nights there, just as though we were still traveling across the U.S. on our way to somewhere.

Next day Pop got some maps of the nearby towns around the college and talked to a few people, and the administration office said they’d give him an allotment equal to the rent of the apartment toward the monthly rental of any house he found. Which meant the house had to be for rent at a pretty cheap price.

After about three days of cruising around in the nearby towns, Drew had to go get more maps. Most of the houses close to the college were already rented or owned by the college professors who had long-term contracts. Those that were left were either too expensive or else they were egg crates.

Inez said it wouldn’t matter even if we moved to a town that was ten or fifteen miles away from the campus, since Drew would have the truck for daily transportation. She herself always used a bicycle for shopping and other errands.

One thing we found out from driving slowly through a lot of small town streets is that people are always glad to see the garbage man. Even though Drew had washed down the truck and it was now back to being filthy white and dirty yellow with big black letters that said it belonged to PINE RIDGE TOWNSHIP in California, you’d be surprised how many people came running out of their houses with bags of garbage as soon as they heard us coming.

One little old lady raced out with a whole bedsheet full of watermelon peels and cantaloupe rinds.

“My, I’m glad you came by this afternoon,” she said brightly. “Not one of your regular pickups, is it? Well, you couldn’t have picked a better time. I’m just putting up my watermelon pickle and I’m so glad to be getting rid of the garbage today before the weekend comes on. Bedsheet’s old, too, so I thought that might as well go. You won’t be coming by again a little later, will you? I’ll have shrimp shells.”

She looked almost ready to cry, standing there on the sidewalk with her torn, bulging bedsheet, after Pop told her we weren’t taking any garbage, only looking for a nice roomy house to rent.

On the other hand, Drew picked up some fantastic junk, even though he had expected the pickings to be slim in the East. One man who had some big black stovepipes sitting out on the sidewalk flagged us down and then asked if we’d like to take a peek in his garage. Inez got a couple of enormous old tubs and dye pots out of that one and also a lyre with three strings missing.

But although junk kept piling up in the truck, we didn’t seem to be getting any closer to finding a place where we would be able to unload it all. By now we were looking around in a town called Havenhurst, about fourteen miles from the college. Like most of the towns we had looked through, it had a mixture of old houses and new houses, a dilapidated old shopping street called Broadway, and a whopping big, neon-lit shopping center called the Havenhurst Shoppers Mall.

We were grinding past a spread-out new ranch house with manicured grass and a red-and-white painted jockey on the lawn when a girl came running down the driveway, all the time yelling over her shoulder, “Hey Ma, the garbage man!”

Only Drew and I were in the truck that day. Inez had gone bicycling to a patch of woods on the north edge of the campus to hunt for mushrooms.

“Step on it,” I said to Pop. “It’s garbage this time for sure. Judging from the size of that kid, they eat a lot in that house.”

Because this girl was fat. And when I say fat, I don’t mean fat. I mean FAT.

“Hey wait, mister,” the fat girl yelled, puffing her way toward us like a steam engine. “Please wait.” And to my surprise, Drew began slowing to a stop. Not because of her, but because just ahead of us at the corner of the street, half hidden by trees, sat an old silvery gray wooden house in the middle of a weed-grown yard and surrounded by a fence with a lot of the pickets missing. And nailed to the fence was a big, tired-looking sign that said THIS PROPERTY FOR SALE OR RENT: INQUIRE CALVIN CREASEY, 108 BROADWAY, HAVENHURST.

By now the fat girl was peering up into the cab of the truck, her cheeks and chin still shaking like jelly from that exhausting run down the driveway and along the street to the truck, maybe a whole twelve yards.

“Gee thanks for waiting, mister,” she gasped up at Drew. “My mother’ll be out in a minute. See, we missed the pickup yesterday and our Dispose-all’s on the blink.”

“Forget it,” I said, leaning over Pop’s shoulder to save him the trouble for once. “We don’t take garbage.”

“You don’t?” She looked pretty mad. Her hair, which was blonde and crinkly, seemed to stand up on end and her eyes, which were the same light hazel color as the freckles all over her cheeks, seemed to turn about three shades darker. She wasn’t bad-looking and I figured she must have been just about my age—eleven, or maybe twelve. But as I said before, was she ever FAT.

“Then what are you riding around in a garbage truck for?” she wanted to know.

“That’s our business,” Drew snapped. He was getting tired of explanations, and what with school opening for me in just one week and classes starting at the college very soon after, the whole thing was getting to be a drag.

“It’s a long story,” I said apologetically.

“Listen,” Drew said wearily to the fat girl. “What can you tell us about that house, the one there on the corner with the FOR RENT sign?”

She followed Drew’s gaze. “That house. Oh, that’s the old Creasey place. Isn’t it awful? No one lives there now. In fact there’s a neighborhood committee to get it condemned and torn down. My mother’s the chairman,” she added proudly.

“Well congratulations and all that,” Pop said.

“But how can we get a look at it? I mean now. Without going back to Broadway and hunting down this Mr. Creasey.”

The fat girl looked at Drew and then slyly shifted her eyes to me. “Well, it’s locked—I guess . . . I mean, it’s still private property. But if someone could crawl through a window. Well, of course, I couldn’t—uh, that is, I wouldn’t. But sometimes some of the neighborhood kids do, the smaller kids, that is. . .”

It took only a few minutes for me to crawl through the living-room window, walk across the creaky dusty floorboards of the big empty living room, and open the front door to Drew and the girl.

“What’s it like, baby? Okay?” Pop brushed past me eagerly. He had a sense for these things—and besides he’d already seen the big yard that surrounded the place. I guess he knew that this was going to be the house.

The fat girl remained standing in the doorway, but I could tell from the way she didn’t seem much interested in looking around that she’d been in the house before.

“It would be great to have somebody like you move into the neighborhood,” she said slowly, eyeing me in a funny way. “But you wouldn’t be thinking of moving in here, would you?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” I said, trying to sound cool about it all. “It’s possible.”

The girl exploded into a burst of laughter, although something about that laugh had a nasty ring to it, too.

“Listen,” she said, sidling up to me in a confidential manner. “Nobody would move in here. This place is a dump. The last people that lived here were so awful they got run out of town.”

“Why?”

She grinned and tossed her head. “Never mind. I don’t tell neighborhood gossip.”

“Then you shouldn’t have mentioned it in the first place.”

“Listen,” the fat girl said, breathing heavily as she got even closer and went into a husky whisper. “The only kind of people who would ever rent or buy this place now is coloreds. That’s why my mother and these other neighbors have this committee. Get it?”

I got it all right. But all I could see as I nodded dumbly was Inez’ face when she heard about this. Mom would be livid. She might even throw things. There were some things she could get pretty sore about and one of them was prejudice.

For a minute I was tempted to tell the fat girl that my Mom was part American Indian and, therefore, so was I. And that was “colored,” wasn’t it? But I decided not to say anything about it just then.

“Look,” I told her. “It’s up to my folks, whatever my Mom and Pop decide. They might just take the place. They’ve got their reasons.” Then I decided to get even with her for what she said earlier. “I can’t say anymore, though. I don’t tell family secrets.”

She looked a little stunned but I could tell she caught on. For a second or two we just stood there glaring at one another.

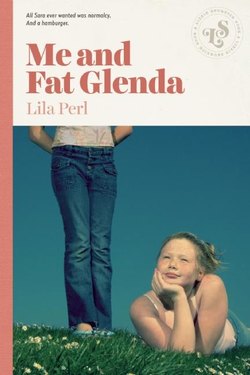

Then, all of a sudden, she broke out into a big picture-window smile. “Well,” she said, real warmly, “if you do move in here, I just know we’d be friends, huh? And I guess your folks would fix up the place so nobody’d ever even recognize it after a month or two.” She paused. “Oh, I s’pose I should introduce myself. I’m Glenda. Who are you?

And that—as I guess you guessed already—is how I met Fat Glenda.