Читать книгу Fastpacking - Lily Dyu - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Welcome to the world of fastpacking

‘We were wilderness running. Power hiking. Kind of backpacking, but much faster. More fluid. Neat. Almost surgical. Get in. Get out. I call it fastpacking.’

Jim Knight in an article in UltraRunning magazine following his 1988 traverse of the Wind River Range, USA. He and his running companion, Bryce Thatcher, completed the 100-mile journey in just 38 hours.

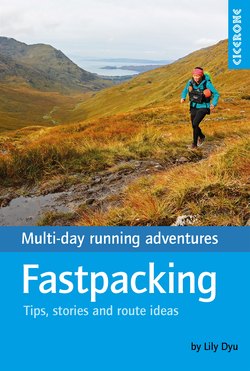

Fastpacking is a great way for runners to explore and discover new places – Vallone di Vallasco, Italy

Fastpacking is a fast-growing niche in the world of trail running. Put simply, fastpacking is the hybrid of running, hiking and backpacking. It’s the art of moving fast and light on multi-day trail running journeys.

To purists, it means being self-sufficient in wild places, experiencing the mountains raw, but there are many styles of trip: from running with a pack between overnight stops, like guesthouses and hostels, to bothying in remote wilderness locations. Hut-to-hut running is increasingly popular in places like the Alps where networks of mountain refuges in spectacular locations provide hot meals and a bed, allowing you to live well and travel light.

Over recent years there has been a boom in trail and ultra-running and stage races. This has evolved into offshoots such as Fastest Known Times, or FKTs, where runners try to set speed records on established routes, such as Damian Hall completing the UK’s 630-mile South West Coast Path in less than 11 days and Kilian Jornet running and climbing over Mont Blanc, starting in Courmayeur and finishing in Chamonix nine hours later.

Multi-day running is not all about times, though. More and more people are pursuing solo running adventures as a way to experience and explore the outdoors. Elise Downing ran the coast of Britain in 301 days, camping and staying with friends, and Anna McNuff covered the length of New Zealand in 148 days, stopping to speak at schools and inspire children to get outside. But you don’t need to go far. It could be an out-and-back running trip from your doorstep or following a local long-distance path at a leisurely pace. Fastpacking is for everyone.

Underpinning the activity is the principle of ‘fast and light’ – taking only what you need to stay safe and happy and nothing more. This allows you to travel further and faster in a day compared to hiking, by running whenever the terrain allows it. You could see it as adventure racing without the race. It’s about exploring and enjoying your surroundings at your own pace. It’s the excitement and fun of ultras and stage races but without the entry fee and cut-off times. There are no medals, t-shirts or personal bests. The reward is the journey itself and the thrill of moving fast and light in the wild. Quite simply, if you love running, fastpacking is a wonderful way to travel and discover new places.

Humans were born to run. Our ancient ancestors were hunter-gatherers, spending days on foot, roaming through the landscape. On a psychological level many of the people who shared their stories for this book spoke of the heightened sense of awareness they experienced in ultra and multi-day running. Such peak experiences and ‘flow’ may be a huge part of the appeal for those who seek solitude in the natural world through fastpacking.

Perhaps the phenomenal growth of fastpacking is a backlash against our increasingly screen-based, sedentary lives and the constant pressure to record and post every run or ride online. It’s a fantastic way to disconnect from our digital lives and reconnect with nature and ourselves. Spending days immersed in the landscape and natural world through fastpacking is, for many runners, a much richer and deeper experience than a trail or ultra race. There is a special satisfaction in making a running journey powered by your own two feet and seeing your surroundings change as you go. And by carrying no more than you need, fastpacking provides a beautiful sense of simplicity and freedom.

A great way to travel. Ridge running in the Black Mountains of Wales

You don’t need to be an ultra athlete or an extreme adventurer to go fastpacking. It’s a lot easier than you’d imagine. And for those who hate planning, there are many companies who will take all of that off your hands, including moving your bags and booking your accommodation, allowing you to just run with a day pack.

This book provides practical tips and advice on organising your own multi-day running trips, including: styles of fastpacking, from supported to unsupported; how to choose a route; where to stay; what to what to take; and eating on multi-day runs.

A question that often comes up when picking a route is, ‘How runnable is it?’ While a person’s ability to run up big climbs and tackle technical terrain is largely a matter of experience, this book also gives overviews and travel tales from 12 tried-and-tested fastpacking routes, including: a wild camping micro-adventure on Dartmoor; running some of the UK’s national trails; and a bothy-run in the Highlands. Overseas, there’s hut-hopping in the Alps and Dolomites, plus a stage race in Nepal on a tea-house trekking route, along with other fastpacking opportunities in the country.

In addition there are a dozen stories from the world of multi-day running enthusiasts and ultra-distance athletes. In the UK these tales range from bothying in the Black Mountains with Anna McNuff to running from Land’s End to John O’Groats with Aly Wren. Iain Harper tackles the Pennine Way in one push, competing in the legendary Spine Race, while Jasmin Paris and her husband, Konrad Rawlik, take a more leisurely approach along the same trails to celebrate her birthday. Further afield, Olly Stephenson takes on the iconic John Muir Trail in the States; Jez Bragg goes hut-to-hut running around Monte Rosa, in Italy and Switzerland; and Anna Frost takes us on a sky-high running journey in Bhutan, the Land of the Thunder Dragon.

By sharing our fastpacking experiences and what we love about multi-day running, we hope that our stories will spark ideas and inspire you to try fastpacking too.

Fastpacking can take you to remote and inaccessible places – Barrisdale Bay, Scotland (Route 8)

How fit do I need to be?

Fastpacking is for all trail runners. It’s not a race and it’s up to you how far you go each day. Slowing down is the secret to multi-day running. Compared to a typical run, you can expect to be much slower, mixing running – probably at the pace of a slow training run – with plenty of power-walking. Few people have the fitness to average more than about three miles an hour on hilly or mountainous routes over several days. That’s not fast; it’s the pace of an average walk.

A word about walking

Fastpacking is just like ultra-running in that you will do a lot more walking than you would on a typical long run. This is due to the extra weight on your back and the fact that you’re doing it for several days. When fastpacking, most people will usually walk the hills, and run the flats and downhills, unless the terrain is very technical. A leisurely pace also gives you more time to enjoy the views!

How do I train for fastpacking?

If you are already a trail runner, then training for fastpacking has the same principles as preparing for stage races. You need to get your legs and body used to sustained effort over multiple days and to be able to recover quickly. Back-to-back runs – for example, a long run on a Saturday and another on a Sunday – are a key component. The length of these runs would depend on the distances you are aiming to cover in your trip. Although not necessary, you could also squeeze in a brisk run on the Friday so you enter the back-to-back weekend fatigued, to get used to running on tired legs.

To get used to running with a pack you should try a couple of long runs beforehand with a pack slightly lighter than the one you’ll be carrying on your trip, perhaps about 5kg.

If you are planning to follow a mountainous or hilly route, you should include hills in your training, to give you leg strength for climbing. Any time spent hiking in the mountains is also great training, because rough trails and big climbs mean you will often be power-walking. Cycling and indoor bike training, such as spinning, are also excellent for building leg strength for hilly terrain.

Strength training of the upper body will prepare your back and shoulder muscles for the effort of running with a pack, while exercises to build core strength will benefit your running posture and speed.

The different styles of fastpacking

Broadly speaking, there are four types of fastpacking – unsupported, where you carry your own food and shelter; running between existing accommodation, such as huts, guesthouses and hostels; self-supported trips, where you might cache food and equipment along the way; and finally, fully supported trips.

Unsupported fastpacking

This is considered by many to be the purest form of the sport because you carry everything you need to be self-sufficient. Your pack will contain a shelter in the form of tent, tarp or bivvy, plus food and sleeping gear. This style is particularly popular in the US where more reliable, dry weather in national parks, such as Yosemite, makes it possible to use a lightweight tent or tarp and carry less clothing, compared to, say, a European or British trip. In the UK, two-day mountain marathon events follow this approach, with runners carrying food and equipment for an overnight camp. Examples of unsupported trips would be two days of running and wild camping in Dartmoor National Park, or taking on the entire Cape Wrath Trail.

Running between existing accommodation

The second variant is running with a small pack between overnight stops, such as mountain huts, guesthouses and hostels. In continental Europe, hut-to-hut running is growing in popularity since there are excellent trail networks coupled with perfectly spaced huts, providing runners with a warm place to sleep and get a hot meal. A lighter pack allows you to enjoy your running more comfortably and to travel further, and by staying in huts you can enjoy the local food and culture, and meet like-minded travellers in the evenings.

Mountain huts are usually in spectacular locations. (Rifugio Morelli – Buzzi, Italy)

Self-supported trips

On these trips, you cache supplies and equipment along the way. An example would be a three-day trip that two runners made across Wales, from Borth on the coast, to Hay-on-Wye on the English border. They doubled up their camping gear by borrowing an extra tent and pair of sleeping bags, and on their drive to the start of the run they dropped off their equipment, along with food for breakfasts and snacks, at two pre-planned campsites en route. They then ran back, sleeping at the campsites and eating in pubs in the evenings. They had to recover their car from the start and collect the camping gear on their drive home, but it was a fun, self-styled adventure.

Supported fastpacking

These are trips where a crew will tend to runners at checkpoints along the route, offering backup in case of an emergency. They are generally the fastest and lightest fastpacking style and also fun and social trips. Every year since 2003, for example, a group of runners from Edinburgh and Aberdeen Hash House Harriers take on an Easter Challenge – a four-day run along a long-distance path or a bespoke route – with a driver and minibus. The end point of each day is the next day’s starting point. By night, instead of camping, the friends return to a hotel for food, drink and a comfortable bed.

Baggage transfer

Although marketed largely to walkers, it is easy to use baggage transfer services (available on many long-distance routes in the UK) for multi-day runs. For a small cost, your gear will be moved between your overnight stops, allowing you to run with just a day pack carrying essentials. Some companies even deliver bags to campsites. Often hotels can organise this for you too, using taxis, and there are now companies that offer self-guided trail-running holidays where all of this is taken care of.

Where to stay

On a multi-day route there may be guesthouses, hostels, bunkhouses and hotels to stay at, but when fastpacking there are additional options that allow you to explore wilder, remote or mountainous areas. These are covered below.

Wild camping

Wild camping means you can stop wherever you find your perfect spot (Photo credit: Chris Councell)

For the purist, fastpacking is about being totally self-sufficient through wild camping and carrying all your own gear and food. This has the advantage of allowing you to travel through remote areas and get off the beaten track. Strictly speaking, in the UK this is only officially permitted in Scotland and Dartmoor.

In Scotland you are allowed to camp on most unenclosed land. However, due to overuse, East Loch Lomond is subject to wild camping byelaws which restricts wild camping in the area. Be sure to familiarise yourself with the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (www.outdooraccess-scotland.scot) – basically, campers should follow a policy of ‘leave no trace’.

On Dartmoor it is legal to wild camp in some sections of the national park. You can find a map on the national park website (www.dartmoor.gov.uk) which shows the permitted areas. Some sites are used as military firing ranges, so you should always check the firing schedules (www.gov.uk – search ‘Dartmoor firing times’) as this would override any permission or right to camp.

Elsewhere, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, wild camping is illegal; the right to stay overnight on open access land is not granted in the Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act. This means that you cannot wild camp unless you obtain the express permission of the landowner first. In practice, this can often be impractical or impossible to do, and wild camping is usually tolerated in more remote areas – typically, more than half a day’s walk from a campsite or other accommodation – as long as it is done sensitively. The following guidelines should help:

Arrive late and leave early

Sleep well above the wall line, away from houses

Leave no trace of your camp and take out all rubbish

Don’t light fires

Toilet duties should be performed 30 metres from water and the waste buried

Pack out all paper and sanitary products

Be respectful at all times; if asked to move on, do so

Aim to leave a wild camping spot in better condition than when you found it

Close gates behind you

Avoid disturbing wildlife, particularly during the moorland lambing and bird breeding season, from 1 March to 31 July

Always remember that landowners have the right to move wild campers on.

Bothies

Inside Strathchailleach (Sandy’s bothy), Sutherland, Scotland

Bothies are free mountain huts in the UK – usually old buildings that are left unlocked for walkers and other outdoors folk to use as an overnight stop. The Mountain Bothies Association maintains, through volunteers, around 100 bothies, mostly in Scotland but with a few in England and Wales, while there are others run by private estates.

Accommodation is basic and camping in a stone tent is a common description for bothying, but they are generally located in wild, remote locations making them a great option for running adventures. When staying in bothies, you will often meet new people, which could mean a memorable evening by a fire, sharing stories, food and a hip-flask.

You will, however, still need to carry most, if not all, of the same gear as you would when wild camping. Assume that there will be no facilities – no water, electricity, lights or beds and if there is a fireplace, there probably won’t be anything to burn. Also, you will need to carry or find water and there may not be a suitable supply nearby. And bothies generally don’t have toilets apart from a spade!

The continued existence of bothies relies on users helping to look after them. The Mountain Bothies Association has developed a Bothy Code which sets out the following guidelines (reproduced with their kind permission):

The bothies maintained by the MBA are available by courtesy of the owners; please respect this privilege

Please record your visit in the bothy log-book

Note that bothies are used entirely at your own risk

Respect other usersPlease leave the bothy clean and tidy with dry kindling for the next visitorsMake other visitors welcome and be considerate to other users

Respect the bothyTell us about any accidental damage. Don’t leave graffiti or vandalise the bothyPlease take out all rubbish which you can’t burnAvoid burying rubbish; this pollutes the environmentPlease don’t leave perishable food as this attracts verminGuard against fire risk and ensure the fire is out before you leaveMake sure the doors and windows are properly closed when you leave

Respect the surroundingsIf there is no toilet at the bothy please bury human waste out of sight. Use the spade provided, keep well away from the water supply and never use the vicinity of the bothy as a toiletNever cut live wood or damage estate property. Use fuel sparingly

Respect agreement with the estatePlease observe any restrictions on use of the bothy, for example during stag stalking or at lambing timePlease remember bothies are available for short stays only. The owner’s permission must be obtained if you intend an extended stay

Respect the restriction on numbersBecause of overcrowding and lack of facilities, large groups (six or more) should not use a bothyBothies are not available for commercial groups.

To find out more, see The Book of the Bothy (Cicerone Press) or the Mountain Bothies Association website (www.mountainbothies.org.uk).

Top tip

Always take a tent, in case the bothy is full, plus a sleeping mat for a more comfortable night’s sleep. There may be a sleeping platform, but if it’s busy you might have to sleep on a stone floor.

Mountain huts

Hut-hopping is great way to travel. Refuge de la Croix de Bonhomme on the Tour du Mont Blanc, France (Route 9)

Hut-to-hut running is a fantastic, cost-effective way of fastpacking through the Alps and other European mountain ranges, and it doesn’t involve carrying a tent, stove or sleeping bag. Running between mountain huts (also known as refuges, rifugios, Hütten and cabanes), where you can get a bed, hot dinner and breakfast, means you only need to carry essential gear; and a lighter pack means that you can move more quickly and comfortably through mountainous terrain.

High-level mountain huts are an alien concept to many British hikers, and yet there are thousands of them across the continent. They are generally situated at a key pass or high on a mountain, without vehicle access and open from June until October, with some open in the spring ski-touring season. Huts can come in all shapes and sizes, and range from the most basic of bivouac shelters for climbers and mountaineers to larger establishments that almost resemble hotels – imagine a high-altitude hostel with cosy bunks and thick blankets, superb views, hearty food, and a common room filled with outdoorsy types from all over the world. Huts let you travel light and live well, costing typically €50 a night for half-board, for a bed in a dormitory or twin room. Although a mattress and bedding are provided, you must also bring and use your own sheet sleeping bag.

Huts are a tourism industry in themselves. In an Italian rifugio, you might enjoy multi-course meals, a bar, proper Italian coffee, showers and drying facilities. Some even have hot tubs outside! Meanwhile, Norway’s huts are often unstaffed and work on a basis of co-operation and trust. You are relied on to make a payment for a stay and food taken from their stores, and to leave things the way you found them. Well equipped, cosy, comfortable and warm, with plenty of firewood, these make a welcoming stay after a day on the trails.

Guidebooks are usually the best source of information on the existence and location of huts, but many refuges now have their own websites giving details of accommodation, facilities and contact details so that you can book ahead. Appendix A includes the websites of the main European Alpine Clubs, where you will also find hut information.

The Mountain Hut Book (Cicerone Press) is an excellent introduction to mountain huts and refuges for walkers and trekkers. It explores the mountain hut experience, from how huts have developed to modern-day hut etiquette, and also includes profiles of the author’s favourite refuges and recommended hut-to-hut routes in the Alps and Pyrenees.

Top tips

Membership of the UK branch of the Austrian Alpine Club – www.aacuk.org.uk – is worth considering as this includes rescue insurance and hut discounts.

Members of the British Mountaineering Council – www.thebmc.co.uk – can buy a Reciprocal Rights Card which gives discounted rates in huts, including those owned by the Alpine Clubs of France, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, South Tyrol, Austria and Spain.

Membership of the Alpine Club – www.alpine-club.org.uk – also provides some hut discounts.

Always check a hut is open when you are visiting. Have an idea of where you will stay and book ahead in high season, when huts will often be busy with both walkers and locals using them for weekend activities. Bed spaces and meals at huts can usually be booked via email and phone.

September is often a great time for Alpine fastpacking. The weather is usually good and, since it’s out of season, the huts usually aren’t as busy.

Where should I go fastpacking?

Breathtaking Glen Affric on a multi-day run across Scotland

As important as it is to pack light, choosing your route is perhaps key to your enjoyment – whether you design your own or follow an existing one. Fastpacking is about running to a place you can’t get to in just a day and there are many ways of doing this, from a short, out-and-back trip with an overnight stay, to doing a national trail over several days, to planning your own journey lasting weeks. Some adventurers have even run around the world.

Fastpacking routes fall into two categories: the ‘loop’, which starts and ends at the same place; and the ‘through route’, which is linear in nature and may require the additional logistics of returning to the start.

For time reasons, loops are often preferred by fastpackers, especially on shorter trips. These make great weekend micro-adventures, such as a two-day run on the Gower Peninsula, stopping at a bunkhouse – but they could be longer journeys, as in a full five-day circuit of Mont Blanc.

Through routes are great for longer trips, giving the satisfaction of making a point-to-point journey under your own steam and seeing your surroundings constantly change. However, you will need to factor in the logistics of travelling back to the start or perhaps to a different location. Trips you could try include taking a train out to a start point and running home over two or three days, or perhaps following an existing long-distance route such as a national trail.

A cloud inversion in the Italian Alps on the Grand Traversata delle Alpi (Photo credit: Chris Councell)

Designing your own route

Researching and planning your own route allows you to take in the landmarks you want to see, trails you want to run or perhaps hills you want to climb.

While training for the Marathon des Sables, for example, two friends ran 25 miles of the Wye Valley Walk, from Hay-on-Wye to Hereford, with an overnight stop at a guesthouse, and then back via the same route the next day.

Another group of fell runners head up to Scotland each year with lightweight mountain marathon gear so they can run and walk their own routes over a long weekend. One of their most memorable journeys was a three-day, two-night trip, parking at Muir of Ord and getting the train across to Attadale on the west coast, then running back and wild camping along the way, far from roads and staying high on the hills. You can simply pick a place you’ve always wanted to visit and design a trip around it.

Approaching Hay-on-Wye at the end of a three-day run across Wales (Photo credit: Chris Councell)

Long-distance walking routes

Choosing established routes, whether in the UK, Europe or further afield, generally means that there will be good transport connections, accommodation and services en route, making organisation and logistics much easier. There are often luggage-moving services available too. From a planning perspective, guidebooks and maps will be readily available, as well as online resources.

The UK has many well-established national trails and fantastic land access for walkers who enjoy the right to roam in much of the countryside and open spaces. You can camp or stay at hostels, bothies, hotels, bunkhouses and guesthouses. On European walking routes you will usually find fantastic networks of mountain huts and budget walkers’ accommodation, making them an excellent choice for fastpacking.

The UK has many national trails that are perfect for fastpacking trips

Another great resource is the Long Distance Walkers Association. Their website gives information on over 1500 long-distance routes in the UK, with links to books, maps and accommodation. For a small annual fee, as a member, you also get access to events and newsletters. See www.ldwa.org.uk

Ultra-marathon race routes

The routes of ultra-marathon races make a great choice for fastpacking trips and their route maps and GPX files are usually available on event organiser websites. Often competitors will use fastpacking as a way of training and doing a route ‘recce’. An advantage of these is that the race route is likely to be very runnable – although there won’t necessarily be much accommodation available along the way.

Top tip

Whether designing your own route or following an existing trail, choose a schedule that leaves room for adventure and taking in the views. It’s not a race!

Key considerations when choosing a route

Distance

What is the total distance of this route? What daily mileage is realistic and achievable? How long do you want to be out for each day? Some people like to start early and finish in the early afternoon, giving them plenty of time to refuel, recover and perhaps wash their gear. You might simply choose to run a standard walking stage each day, giving you more time to stop at cafés, enjoy the views and explore in comparison to walking; while more experienced runners may opt for full 12-hour days in the mountains. It’s a personal choice, to be decided by factoring in all information about the route.

Height gain and loss

What is the total daily ascent and descent? This is critical to how far you can cover each day. In fastpacking you will be generally walking the climbs and running the descents and flats and this is how you gain time compared to walking, thus allowing you to go further. But if your route is exceptionally hilly, with lots of steep climbs, technical descents and little flat, you may find that it’s impossible to run and you will actually be no quicker than a hiker.

Following a balcony path on the Grande Traversata delle Alpi, Italy

Difficulty of the terrain

This is crucial to your safety and also how far you can realistically travel in a day. How technical is the terrain? Will you be on smooth, easy, well-made trails that are easy to run on? Will rocky, rough ground slow you down on the flat? Does a steep, technical descent mean you won’t be able to run downhill? Will there be river crossings that slow you down or require a lengthy diversion? Again, very technical terrain means that you may not be able to do much running.

Some routes include scrambling and exposure, which you may not be happy doing, especially in running shoes and certainly not without previous experience. On many Alpine routes there may be trails with via ferrata, or aided and assisted sections using ropes and ladders. In fastpacking you won’t be in the same gear as a hiker and these could be treacherous in running shoes and without the right equipment. Read all available information about a route carefully and decide if it’s within your capability.

Always check what terrain to expect and whether it’s within your capability (Passo di Ciotto Mieu, Italian Alps)

Top tips

Research and plan your route thoroughly and understand its technical difficulty.

If considering a mountainous route, read a guidebook beforehand, using a highlighter to pick out technical sections. Consider these carefully before making a final route choice. Partway through a multi-day mountain trip is too late to discover that there are sections of route that you are not equipped for or sufficiently experienced to undertake.

Be flexible. There is no shame in missing out sections and using public transport to connect up more runnable, scenic and interesting sections.

Identify escape points where you can leave a route if necessary.

Plan for recoverable daily efforts. On any multi-day trip, aim to be just as strong on the last as you were on the first day.

Navigation

Although spending time navigating may slow your running pace, it’s easy to overshoot and miss a turn when running, so it’s worth stopping regularly to check your location. Always carry a map and compass and know how to use them. A good navigator will always have these to hand, rather than in their pack. Ensure you are competent in navigating in poor conditions.

Always know where you are on the map when following a route. It’s easy to forget to check this while you’re caught up in the flow of running, but you don’t want to suddenly reach a path junction and wonder where you are. While you’re running it can be difficult to keep track of your position and this will mean you need to re-find your location each time you look at the map. To get around this, a good technique to use is ‘thumbing the map’. This simply means always having your thumb next to your current position on the map and moving it along the route, as you compare map features to the observed terrain, while you run.

Obviously, night navigation experience is a bonus if you’re caught late on the trails due to unforeseen circumstances. In these situations, you should also act with risk aversion in mind and try to find the easiest route to navigate – for example by switching to quiet roads rather than mountain paths to get to your destination.

Always factor in navigation when estimating your running pace

Mobile phones and GPS devices

There are, on the market, countless GPS devices, including GPS watches that can navigate for you. There are also many useful GPS apps available for smartphones – if you’re buying one, choose a product that lets you download maps so you can view them offline. These apps will locate your position on a map even if you have no mobile coverage; this can be useful for cross-checking your location. A very popular GPS app is Viewranger – www.viewranger.com – which runs on both iOS and Android devices and can be downloaded from the Apple App Store or Google Play.

Don’t rely solely on electronic equipment for navigation as it can fail, or you may find you are unable to charge your device on your trip. A good rule is to treat a smartphone as an emergency device. Be aware that batteries run down more quickly in the cold. Always use a waterproof cover. Keep your device safe in a pocket in a waterproof bag, in airplane mode, with no apps running in the background to conserve battery life. Rely on your own navigation skills.

Safety

The most important thing a runner will take on a fastpacking trip is their outdoor know-how. Mountain weather can change very quickly; you need to have the skills to take care of yourself and others before you head into the mountains and remote places. These include navigation, first aid, what to do in an emergency, river crossings, and an understanding of mountain weather, hypothermia and the effects of heat.

If you are not skilled enough to hike a route, then never fastpack it, since running increases your risk of an accident. Fastpacking presents unique challenges compared to hiking, since you will be in different footwear and probably carrying less equipment and clothing.

That said, some people have argued that going lighter and faster allows you to remove yourself from risks, like poor mountain weather, more quickly. This clearly depends on your experience and you should never compromise on safety when making gear choices. It’s a classic balance of your experience, the likely conditions, terrain and carrying the necessary gear to be safe.

Top tips

Start early each day. This provides contingency in case something unexpected happens, like getting lost or encountering poor weather.

Make sure you know what weather conditions are likely. Are afternoon thunderstorms common in the region you’re planning to fastpack in? Will there be snow and ice on a high pass? Ensure you know how to deal with these situations.

Build your experience by trying fastpacking on shorter trips before attempting long-distance routes. Learn as you go and build skills and confidence.

Fastpacking means going fast and light, but without compromising safety. Never omit essential clothes and equipment for the conditions, no matter how light you’d like your pack to be.

Take a charged phone and avoid using it apart from in emergencies.

Ideally, go fastpacking in company.

Leave your itinerary with someone at home. Make sure someone knows where you are going to be and when you should be expected to return, especially if you are travelling solo.

Plan for emergencies and have exit points planned along your route so that, if necessary, you can get out safely.

How to get started

It’s a good idea to start with a simple overnight trip, for example running a circuit close to home that includes an overnight stay, or an out-and-back route. You could take the train somewhere and then run back to your start. Short trips allow you to build up experience of back-to-back running days while carrying a pack.

The UK’s national trails are a great way to try fastpacking and generally these aren’t technically difficult or very mountainous. You could opt to use a baggage service to move your gear and this would let you get used to running longer distances over consecutive days, before carrying the weight of a heavier pack.

What to take

The contents of my rucksack for two weeks in the Italian Alps

Obviously, what you carry will depend on the type of trip you’re doing, whether you’re camping or running between accommodation, but the key principle in fastpacking is to travel as light as possible. A heavy pack will make it both uncomfortable and impossible to run. But you should never compromise on safety – you need the right gear to take care of yourself and to be prepared for the likely conditions. Carry exactly what you need to be safe and happy, and nothing more. A full suggested kit list is provided in Appendix B.

A word on weight

The weight of your pack is the number one and most crucial factor for enjoyable and successful fastpacking! This cannot be over-emphasised. Aim for a pack weight of 3–8kg. Anything above 8–10kg will be difficult to run with and increases your risk of injury. The rise in ultra-lightweight outdoor gear makes this much easier now, but it can be as simple as being ruthless about what you take and thinking carefully about your food choices. Some people even cut the straps off their packs and the handles off their toothbrushes to reduce weight – but there has to be a balance. Even when packing minimally, you should always have the right gear for the terrain and likely weather.

The weight of your pack is the most crucial factor for enjoyable and successful fastpacking

Backpacks

Your pack is your most important piece of kit and needs to be comfortable, fit well and hold all your gear. There is an excellent range available due to the growth in ultra-running, so it’s just a matter of finding one that rides well on your body and meets your needs. Here are some factors to consider when choosing:

Volume – when wild camping you will need 25–30 litres; for an Alpine hut-to-hut trip, 15–25 litres is probably sufficient; and for a UK national trail using existing accommodation, 10–15 litres is plenty

Comfort – choose a pack with a soft back-pad that moulds to the shape of your back

Stability – comfortable and stabilising straps around the shoulders and across the sternum are crucial. You should be able to pull the waist belt, shoulder straps and chest strap tightly to eliminate as much movement of the pack as possible

Rubbing – when running, there should be very little motion of the pack against your back, both horizontally and vertically. If your pack moves, it will make it hard to run and lead to painful pack-rub

Pockets on the waistband or straps are useful for quick access to essential items such as head torch, snacks, map and compass, and camera. With some packs, you can also buy map pouches that attach to the front of the pack

Camera access – invest in a specialist pouch that can be attached to your chest straps at the front, or waist belt, allowing easy access. If your camera is in your main pack, you are unlikely to use it.

Top tips

Before buying a pack, try running with it, loaded with some gear.

Women may find that many unisex packs don’t fit well, even with straps pulled tightly. In recent years, however, designers are paying attention to the need for a good fit on different body sizes, so the range has improved with women-specific packs available. Make sure you test the pack.

Keep your clothes, sleeping bag, and any electronic equipment dry by putting them in ultra-light waterproof stuff sacks or plastic bags. Freezer or Ziploc bags are ideal. In addition to this, a waterproof cover for your pack will prevent it becoming heavy and sodden in rain. Also watch out for sweat soaking into your pack from your back.

Sleeping bags

Your sleeping bag needs to pack down small without compromising on warmth. Much of your recovery happens when you are sleeping, so being comfortable at night is important. Down sleeping bags are lighter and pack down smaller than their synthetic counterparts; however, a good ultra-light down sleeping bag is not cheap. If your bag gets wet then synthetic will be warmer than down because feathers clump together.

Your sleeping bag will be a personal choice and what you take will depend on the expected conditions. You can also buy fleece liners or consider a silk liner for additional insulation. Your spare clothes packed into a stuff sack will make for a comfy pillow.

Sleeping mat

A sleeping mat is worth the extra weight for the added comfort and insulation from the ground. In bothies these will provide cushioning from the sleeping platform or stone floor.

Foam mats are cheap, light, comfortable and good at insulating against the cold but are cumbersome to carry. Self-inflating mats tend to be fairly light (but often a little heavier than foam), comfortable and pack down small, but are usually much more expensive. There are some very lightweight mats on the market that you can inflate with your breath or even using a ‘pump sack’, which is a stuff sack that doubles as a pump. Some mats are now designed with gaps and holes to reduce weight. As with sleeping bags, there are many options available.

Many running packs, designed for mountain marathons, have a removable back pad that you can use as a sleeping mat beneath your upper back and shoulders. Some people might make do with this, cushioning the rest of their body with their empty pack. If you want to try this, experiment with a one-night trip first.

Shelters – tent, tarp or bivvy?

When should you take a tent versus a tarp? Your choice of shelter depends on the weather and how exposed you are prepared to be. If you are likely to encounter heavy rain or insects, a tent will provide more space, comfort and protection. If it’s going to be dry, you might be happy with a lightweight tarp – a rectangle of nylon or plastic that you set up as a shelter in whatever way best suits your needs. A tarp means sleeping without any walls, groundsheet or insect netting but you will be more connected with nature, as you are essentially sleeping outdoors.

There are also tarp tents, a lightweight hybrid of the two, but as with other outdoor gear there’s a direct correlation between the cost of gear and how much it weighs. Super-lightweight tents and tarp tents that you may like to use on a fastpacking trip aren’t cheap.

Finally, a bivvy bag or even just sleeping bag without a shelter are both options if the weather is going to be good. Read Ronald Turnbull’s classic Book of the Bivvy (Cicerone Press) for advice and amusing accounts of his bivvying adventures.

Camping beneath a tarp while fastpacking on the John Muir Trail, Sierra Nevada, United States (Photo credit: Olly Stephenson)

Tents

Most one or two-person tents weigh around 2kg but advances in materials have seen weights come tumbling down to nearer 1kg or less, although lighter tents will be more expensive. A new tent may be unsealed, seam-sealed or fully waterproof with factory-taped seams. Water can potentially find its way into any tent through needle holes in the seams or through an accidental pinhole or tear, so it’s worth checking the manufacturer’s recommendations for seam-sealing your shelter if this hasn’t already been done. This is usually straightforward and simply means applying a sealant product (available from outdoor stores or online) to all the tent seams. Most commercially available tents have been factory seam-sealed and some will need to be re-sealed every few years, to keep your shelter in good condition.

Top tip

When fastpacking with a second person, split the tent and camping equipment between you.

Tarp tents

A tarp tent is a tent with wall, insect netting and groundsheet but it is significantly lighter than a regular tent because it combines the rain fly-sheet and inner tent into a single wall instead of two layers. Besides its weight, another advantage is that it sets up very quickly in the rain because the entire tent pitches as a complete unit. In addition, some tarp tents can be pitched using hiking poles instead of having to carry additional tent-poles, saving further weight, and some can be turned fully into a traditional tarp, without a groundsheet, in good weather.

Tarps

If you go for a tarp, be sure to try it out before starting your trip, to practise pitching it as a shelter – perhaps even using your running poles. Think about whether you want a groundsheet and/or bivvy bag to complement it. A groundsheet is good if you’re fastpacking in climates where the ground is perpetually damp or if wet weather is expected. Some people even forgo this and sleep on their waterproof gear to save extra weight. Heavy dew can soak a sleeping bag, so some people choose to pair a tarp with a lightweight bivvy bag. Additionally, if bugs and insects are likely to be an issue, you could consider buying a lightweight mesh shelter for extra protection.

Bivvy bags

Bivvy bags are another lightweight option and provide a fully waterproof tube into which you put your sleeping bag. Some also provide a bug screen that goes over your face. You could use this set-up in lieu of all other shelters, but always look for a bivvy bag with breathable fabric, otherwise you may have an issue with moisture from inside the bivvy soaking your sleeping bag.

Head torch

The head torch you should take on a fastpacking trip will depend on how you plan to use it. If you will be doing any night running and hiking, you’ll need something with a powerful output for route-finding and good vision on the trail. Something less powerful and lighter may be sufficient if you are just using it at camp or at your accommodation. Always consider carrying spare batteries.

Top tip

Always carry a head torch on a fastpacking trip, in case you make slower progress than planned and accidentally end up on a trail in the dark or fading light.

Running poles

In mountainous terrain, running poles help enormously with the climbing and technical descents. They reduce effort and impact and help when you’re getting tired. They are also useful for crossing rivers and for testing marshy ground, to see how deep bogs are. There are lightweight poles on the market designed specifically for runners, which can be folded down easily.

Running poles are invaluable in mountainous terrain. (Above Rifugio Genova, Italian Alps)

Clothing

Your clothes will be a significant weight in your pack, and the goal here is to pack minimally while ensuring you have everything you need for the expected conditions. It’s a classic balancing act that requires you to question whether every item has a place on your trip.

While more experienced ultra-runners might manage a hut-to-hut trip carrying only the compulsory kit for the Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc (UTMB) race, others might want more gear – but always remember that pack weight will significantly affect your enjoyment of the trip.

General advice

Always take waterproof trousers and jacket, with fully taped seams, even if the forecast looks benign. Conditions can change unexpectedly and hypothermia is potentially fatal. Even if it doesn’t rain, these provide extra insulation and a windproof layer.

Waterproofs should be fully breathable because you will be sweating from running. They will also be subject to increased rubbing from your pack due to your running movement, so it helps to re-proof these regularly.

Merino wool tops are brilliant for fastpacking. They do not smell even after being worn for days, which means that you can usually manage a trip with one or two tops that won’t need hand-washing. They come in different thicknesses and you can get lightweight t-shirts, vests or thicker base layers. You can also get merino underwear and leggings.

Avoid thick seams on tops because these will rub between your pack and skin. Where seams are unavoidable, choose flat-locked seams.

Wear a top that will cover the entire surface area of your pack. Fastpacking in a sports bra or a vest will rub your skin where the pack is in contact with it.

Women should look for seamless sports bras, with close-fitting and flat straps.

Consider cutting out labels to avoid chafing.

Always consider multi-use for different items of gear. A pair of running tights will be travel-wear, evening-wear or running-wear when it’s cold or wet. A fleece top for the evening will be an extra running layer if it gets cold. A Buff could be a beanie, headband, travel towel or wrist sweat-band.

Whatever you wear on your legs, whether shorts, capri or tights, it is critical that these do not chafe.

Carry detergent so you can hand-wash shorts and underwear. This helps to prevent chafing. Technical fabrics will usually dry out overnight. You can also use cord to attach these to your pack to dry during the day.

Do not try anything new. Stick to tried and trusted gear that you are happy with on long runs carrying a pack.

Make sure you’re prepared for quickly changing weather (Reichenbach stream, Switzerland, Route 11) (Photo credit: Chris Councell)

Top tips

Pack for your destination and the worst conditions you might encounter. If it’s 30 degrees outside a city hotel room when you’re packing, don’t forget that in an Alpine hut at 3000m you may see snow even in summer.

Travel wearing your spare running gear and running shoes. Don’t carry around spare clothes for your flight or return journey – this is dead weight. Accept that you will look like a gnarly adventurer from when you leave your front door. This also makes life simple since you have no clothing choices to make!

For overseas trips, if starting and returning to the same place, you can leave a bag of gear at a hotel, airport or train station for your return journey or the rest of your trip.

Footwear

As fastpacking can be done in any environment, footwear should be chosen based on the conditions you will encounter and the distance you plan to travel. Shoes are a highly personal choice, but here is some general advice:

For long distances over multiple days, trail-running shoes with plenty of cushioning and protection are ideal. Protection around the foot and toe box is needed to protect your feet on rocky trails

Cushioning is crucial. Without enough cushioning, days of running on hard trails can bruise the soles of your feet and this can end your trip. Stones and rocks jab up into the soles of your shoes more when you are running with a pack. Inserting Sorbathane insoles into your shoes is good for extra cushioning

On rocky, wet trails, or grass and mud, you will want a shoe with a good traction for that terrain. Trusting the grip on your shoes is crucial to safety and can also make the difference between loving and loathing your trip

Test shoes in the terrain that you are likely encounter, especially if you are heading into mountains. Wearing trail-running shoes on mountain footpaths is very different to walking boots, which usually have better grip on wet rock, plus ankle support

A luxury item is flip-flops or lightweight canvas shoes. These are not essential but it’s nice to get out of running shoes at the end of the day. Many mountain huts provide Croc-type plastic shoes.

Top tip

If you don’t have a second pair of shoes for the evening you can keep your socks dry in damp shoes by wearing plastic bags on your feet – a favourite tip of mountain marathon competitors.

Running gaiters

Running gaiters are handy for keeping stones and debris out of your shoes. They may also help to keep your feet and socks dry.

Micro-spikes

These are worth considering if you think you may encounter any late snow on Alpine routes in the summer. However, they are not adequate for glacier crossings, which would be a whole book chapter on their own.

Waterproof socks

Gore-Tex waterproof socks are great for keeping your feet warmer and drier for longer than ordinary socks, but they’re not cheap. If you only have damp running shoes to wear in the evenings, these will help keep your feet dry. They won’t keep all water out – for example if you ford a stream where the water is above the sockline – and they also take longer to dry out after washing than ordinary socks.

Top tip

Take care with foot placement while fastpacking. On a trip where you’re jogging and hiking all day with weight on your back, rocks and stones jabbing into your feet will start to hurt a lot. Watch the ground and try to land on flat surfaces when you can.

Food

While fastpacking, even if you’re not covering a marathon distance each day, your daily energy requirements may be comparable to those for a marathon – or even greater – due to the demands of carrying a pack and the hilly or mountainous terrain. Unlike in a marathon, your body will not have the benefits of rest and recovery, since you will be making these demands over sustained multiple days.

Eating and nutrition will therefore play an important role in your trip. Fastpacking gives you licence to eat a lot! It’s important to eat frequently while you’re moving and to adequately refuel in the evenings. Runners will have their own preferences for food and an eating schedule, but the main advice here is to remember your energy requirements will be high and to ensure that you stay fuelled and hydrated throughout.

As a vegetarian, this was not one of my best mountain hut dinners! (Photo credit: Chris Councell)

Food on unsupported trips

Fastpackers who wild camp fall into two categories when it comes to food: cold or hot. Some people carry only food they can eat cold, so they can avoid taking a stove and fuel. For others, a hot drink and meal at the end of the day is worth the extra weight, especially if it’s been wet and cold.

Each runner will have their own preferences for camping food and eating while moving, so no advice is included here on specific products; however, for a trip over multiple days, weight will be key. Some people take a scientific approach to researching and choosing the most calorie-dense foods and matching the quantities to their daily energy requirements.

Top tip

If you are headed into colder conditions, take an extra 500 calories per day as your energy needs will be higher, in order to maintain your body temperature.

Cooking and eating utensils

Choose a camping stove that is small and lightweight and will heat up water quickly. A collapsible cup, which you can use to eat hot food, and a Spork are good choices to keep weight down.

Preparing a fastpacking dinner in a bothy (Photo credit: Tori James)

Food on non-camping trips

If you aren’t camping, and are running between accommodation, then you have options. In the evenings you can dine in, eat out or perhaps self-cater, depending on your lodgings and access to shops. During the day you can carry a packed lunch and your own snacks; buy your food en route; or stop for lunch at a pub, café or mountain hut.

Runners will know from experience what is likely to suit them best. Some people carry gels and bars while others find these get sickly and prefer ‘real’ food. In the Alps, some people might manage by grazing as they run, while others might stop for a proper meal in a refuge, where they can also replenish their snacks. If you’ve become wet and cold, the benefits of a hot meal and drink can’t be overstated.

Guesthouses and mountain huts can often provide a packed lunch. Check your route to see if you pass towns and villages where you can buy food, so that you don’t need to carry much. Always carry at least 400 calories of spare food or gels in case of emergencies.

Water

Staying hydrated while fastpacking is critical, given the high levels of exertion from running long distances with a pack. You should drink plenty of water and have your water bottles or bladder drinking tube easily accessible at the front of your pack. As well as drinking on the trail, it is also crucial to rehydrate well in the mornings and evenings during your trip. This is to avoid the risk of severe dehydration which is a possible cumulative effect of multiple back-to-back days of being dehydrated.

As weight is key, you should plan carefully how much water to carry and where you can fill up en route. It is therefore critical, when planning, to understand where your water sources are going to be, whether that’s a shop, a stream or a mountain hut that you’ll be passing.

If you’re wild camping you should aim to camp near a river or stream. This will mean studying your map and route carefully so that you know where you’ll be able to get water. Most bothies are near a water source and this is generally shown on the MBA website (www.mountainbothies.org.uk). It’s worth investing in a lightweight, collapsible water carrier for these trips.

While some people drink from rivers and streams without treating the water first, it is best to always err on the side of caution. Nasty water-borne diseases are easy to pick up.

The simplest way to purify water is by boiling it on your camping stove. If you want to save fuel, you can buy chemicals or purification tablets to treat water. If you are squeamish about muddy-looking water, you can filter larger particles out through a Buff first. Other options are lightweight filters, ultra-violet filters and even a straw with a filter on it which lets you drink straight from the water source.

Whichever method you use, always try to take water from a fast-flowing stream, as opposed to standing water, and preferably above the tree line. Avoid areas where there are cattle, sheep or other livestock as there could be a dead animal upstream, or water-borne bacteria from livestock.

Tips for staying happy and healthy

Women should be aware that the menstrual cycle can be affected by physical, physiological and emotional stress, all of which can occur at high altitude. Periods can be missed altogether, or become heavier, longer, shorter or irregular. Jet lag, physical exertion, cold and weight loss can also alter the pattern. Be aware of this particularly if you are fastpacking at high altitude. Pack sanitary items even if you aren’t expecting your period during your trip.

Carry antibacterial gel and practise good hand-hygiene.

Use tape to cover areas on the soles and heels of your feet that you know are prone to becoming hotspots.

Carry toilet paper in case you get caught out. Bury toilet waste and either burn or carry out toilet paper and sanitary items.

Use Vaseline to prevent chafing. Sustained, multiple days of running can result in chafing even for runners who’ve run countless marathons with no previous issues. This can ruin your time outdoors.

Sunglasses are a must for high-altitude routes and also protect your eyes from the glare from rock and snow.

At the end of the day, immersing your legs in cold water, whether in a bath, shower or river, followed by hot water where possible, is great for preventing muscle soreness.

Be prepared to make emergency repairs to kit, clothes and packs, and carry spare shoe laces.

Carry and use a chap stick for the harsh conditions of sun, wind and altitude.

Take care of issues early – as soon as they arise – to prevent them spoiling your trip. Don’t wait until a hotspot on your foot becomes a blister, or for your back to be rubbed raw from your pack.

Chilling your legs in icy water can help to reduce muscle soreness