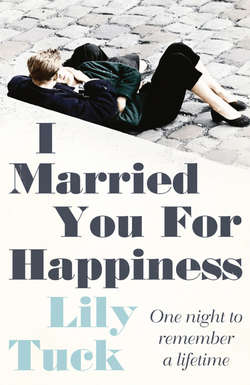

Читать книгу I Married You For Happiness - Lily Tuck - Страница 6

ОглавлениеThe Beginning

His hand is growing cold; still she holds it. Sitting at his bedside, she does not cry. From time to time, she lays her cheek against his, taking slight comfort in the rough bristle of unshaved hair, and she speaks to him a little.

I love you, she tells him.

I always will.

Je t’aime, she says.

Rain is predicted for tonight and she hears the wind rise outside. It blows through the branches of the oak trees and she hears a shutter bang against the side of the house, then bang again. She must remember to ask him to fix it—no, she remembers. A car drives by, the radio is on loud. A heavy metal song, she cannot make out the words. Teenagers. How little they know, how little they suspect what life has in store for them—or death. They may be drunk or stoned. She imagines the clouds racing in the night sky half hiding the stars as the car careens down the dirt road, scattering stones behind it like gunshot. A yell. A rolled-down window and a hurled beer can for her to pick up in the morning. It makes her angry but bothers him less, which also makes her angry.

A tune begins going round and round in her head. She half recognizes it but she is not musical. Sing! he sometimes teases her, sing something! He laughs and then he is the one to sing. He has a good voice.

She leans down to try to catch the words:

Anything can happen on a summer afternoon

On a lazy dazy golden hazy summer afternoon

She is almost tempted to laugh—lazy, dazy? How silly those words sound and how long has it been since she has heard them? Thirty, no, forty years. The song he sang when he was courting her and a song she has rarely heard before or since. She wonders whether it is a real one or a made-up one. She wants to ask him.

Gently, with her index finger, she turns the gold band on his ring finger round and round. Her own ring is narrower. Inside it, their names are engraved in an ornate script: Nina and Philip. Over time, however, a few of the letters have worn off—Nin and Phi i. Their names look like mathematical symbols—how fitting that is.

Nothing is engraved inside his ring. The original ring slipped off his finger and disappeared into the Atlantic Ocean while he was sailing alone off the coast of Brittany one summer afternoon.

A lazy dazy golden hazy—the tune stays in her head.

In the morning when he leaves for work, Philip kisses her good-bye and in the evening, when he returns home he kisses her hello. He kisses her on the mouth. The kiss is not passionate—although, on occasion, it is playful, and he slips his tongue in her mouth as a reminder of sorts. Mostly, it is a tender, friendly kiss.

How was your day? he asks.

She shrugs. Always something is amiss: a broken machine, a leak, a mole digging up the garden. She never has enough time to paint.

Yours? she asks.

What was his answer?

Good?

He is an optimist.

We had a faculty meeting. You should hear how those new physicists talk! Philip shakes his head, taps his forehead with his finger. Crazy, he says.

But Philip is not crazy.

Despite the old saying—said by whom?—about how mathematicians are the ones who tend to go mad while artists tend to stay sane.

Logic is the problem. Not the imagination.

With her fingers, she traces the outline of his lips. Her head fills with images of bereaved women more familiar than she is with death. Dark-skinned, Mediterranean women, women in veils, women with long messy hair, passionate, undignified women who throw themselves on top of the bloody and mutilated corpses of their husbands, their fathers, their children, and cover their faces with kisses then, forcibly, have to be torn away as they howl and curse their fate.

She is but a frail, wan ghost. With her free hand, she touches her face to make sure.

On their wedding day, it begins to rain; some people say it is good luck, others say they are getting wet.

She is superstitious. Never, if she can help it, does she walk under a ladder or open an umbrella inside the house. As a child she chanted, Step on a line, break your father’s spine. Even now, as an adult, she looks down at the sidewalk and, if possible, avoids the cracks. Habits are hard to shed.

He is not superstitious. Or if he is, he does not admit to it. Superstition is unmanly, medieval, pagan. However, he does believe in coincidence, in good luck, in accidents. He believes in chance instead of cause and effect. The probable and not the inevitable.

What is it he always says?

You can’t predict ideas.

The rain has briefly turned into snow. Flurries—most unseasonal for that time of year. She worries about her shoes. White high-heel satin shoes with little plastic pink rosebuds clipped to the front. Months later, she tries to dye the shoes black but they come out a dirty brown color.

She should have known better. Black is achromatic.

A country wedding—small and gloomy. The tent for the reception, set up on her parents’ lawn, is not adequately heated. The ground underfoot is soggy and the women’s shoes sink into the grass. The guests keep their coats on and talk about the U-2 pilot who was shot down that day.

What is his name?

Mark my word, there’s going to be U.S. reprisals and we’re going to have a nuclear war on our hands, she overhears Philip’s best man say.

Someone else says, Kennedy’s hands are tied as are McNamara, George Ball, Bundy, and General Taylor’s.

The best man says, Kennedy is a fool.

What else can he do? a woman named Laura asks him.

Don’t forget the Bay of Pigs. Our fault entirely, the best man replies. He is getting angry.

Let’s not talk politics. We are at a wedding. We are supposed to be celebrating, remember? Laura says. She, too, sounds angry.

Laura, the last she has heard, is living in San Francisco with another woman who is a potter. The best man was killed in an avalanche. He was skiing in powder down the unpatrolled backside of a mountain in Idaho with his fourteen-year-old daughter. She, too, was killed. Her name was Eva Marie—named after the actress, she supposes.

Anything can happen on a summer afternoon

Stop, she thinks, putting her hands to her ears.

Rudolf Anderson—the name of the U-2 pilot who was shot down.

Strange what she remembers.

How, for instance, once, in Boston, when she was in college, she caught sight of Fidel Castro. She still remembers the excitement of it. Dressed in his olive green fatigues, he had looked good then. He was thirty-three years old and he wore his hair long and sported a shaggy beard. Catching her eye, he smiled at her. Of this she is certain. But she was not a true radical; on the contrary, looking back, she appeared timid.

Pretty and timid.

Again she thinks about those dark-skinned, Mediterranean women, women in veils, women with long messy hair, and she wishes she could beat her breast and wail.

For their honeymoon, they go to Mexico, to look at butterflies.

Butterflies? Why? Nina tries to object.

Monarch butterflies. Millions of them. It’s still early in the migratory season, but I’ve always wanted to see them. And afterward we can go to the beach and relax, Philip promises.

The car, an old Renault, is rented, and the roads are narrow and wind steeply around the Sierra Chincua hills as they drive from Mexico City to Angangueo. There are few cars on the road; the buses and trucks honk their horns incessantly and do not signal to pass. There are no signs for the town.

Donde? Donde Angangueo? Philip repeatedly shouts out of the car window. Standing by the side of the road, the children stare at him in mute disbelief. They hold up iguanas for sale. The iguanas are tied up with string and are said to be good to eat.

Supposedly they taste like chicken, Philip says.

How do you know? Nina asks.

Instead of replying, Philip reaches for her leg.

Keep your hands on the wheel, Nina says, pushing his hand away.

In Angangueo, they stay in a small hotel off the Plaza de la Constitución; there are no other tourists and everyone stares at them. Before they have dinner, they go and visit the church. On an impulse, Nina lights a candle.

For whom? Philip asks.

Nina shrugs. I don’t know. For us.

Good idea, Philip says and squeezes her shoulder.

The next morning, when they get out of bed, their bodies are covered with red bites. Fleas.

Following the hired guide, they hike for over an hour along a winding, narrow mountain path, always going up. They walk single file, Philip ahead of her. Tall and thin, Philip walks with a slight limp—he fell out of a tree and broke his leg as a child and the tibia did not set properly—which gives him a certain vulnerability and adds to his appeal. Occasionally, Nina has accused him of exaggerating the limp to elicit sympathy. But most of the time, his limp is hardly noticeable except when he is tired or when they argue.

The day is a bit overcast and cool—also they are high up. Eight or nine thousand feet, Philip estimates. Hemmed in by the tall fir trees, there is no view. It is humid and hard to breathe. How much farther? She wants to ask but does not when all of a sudden the guide stops and points. At first, Nina cannot see what he is pointing at. A carpet of orange on the forest floor. Leaves. No. Butterflies. Thousands and thousands of them. When she looks up, she sees more butterflies hanging in large clusters like hives from tree branches. A few butterflies fly listlessly from one tree to another but mostly the butterflies are still.

They look dead, she says.

They’re hibernating, Philip answers.

On the way back to town, Philip tries to explain. There are two theories about how those monarch butterflies always return to the same place each year—amazing when you think that most of them have never been here before. One theory says that there is a small amount of magnetite in their bodies, which acts as a sort of compass and leads them back to these hills full of magnetic iron, and the second theory says that the butterflies use an internal compass—

Nina has stopped listening. Look. She points to some brilliant red plants growing under the fir trees.

Limóncillos, the guide says and makes as if to drink from something in his hand.

Sí, Nina answers. By then she is thirsty.

From Angangueo, they drive to Puerto Vallarta, where they are going to spend the last few days of their honeymoon. In the car, Nina shuts her eyes and tries to sleep when all of a sudden Philip brakes and she is thrown against the dashboard. They have hit something.

Oh, my God. A child! Nina cries.

A pig has run across the road before Philip can stop. His back broken, the pig lies in the middle of the road, squealing. Each time he squeals, dark blood fills his mouth. Within minutes and seemingly from out of nowhere, men, women, and children have gathered by the side of the road and are watching. Philip and Nina get out of the car and stand together. It is very hot and bright.

Putting her hand to her head to shade her eyes, she says, Philip, do something. The pig sounds just like a baby.

What do you want me to do? Philip answers. His voice is unnaturally shrill. Kill it?

A man wearing a straw hat approaches Philip. The man is carrying a stick. Philip takes his wallet out of his back pocket and, without a word, gives him twenty dollars. The man takes the twenty dollars and, likewise, does not say a word to Philip.

Back in the car, Nina and Philip do not speak to each other until they have reached Puerto Vallarta and until Nina says, Look there’s the sea.

Then, he tells her about Iris.

An accident.

In bed that night, Philip says, I wonder if the guy in the hat carrying the stick was really the pig’s owner. He could have been anyone.

Yes, Nina agrees. He could have been anyone.

These flea bites, she also says, are driving me crazy.

Me, too, Philip says, taking her in his arms.

She believes Philip loved her but how can she be certain of this? Knowledge is the goal of belief. But how can she justify her belief? Through logical proof? Through axioms that are known some other way, and by, for instance, intuition. Who thought of this? Socrates? Plato? She does not remember; she only remembers the name of her high school philosophy teacher, Mlle. Pieters, who was Flemish, and the way she said Platoe.

She should reread Plato. Plato might comfort her. Wisdom. Philosophy. Or study the Eastern philosophers. Zen. Perhaps she should become a Buddhist nun. Shave her head, wear a white robe, wear cheap plastic sandals.

She hears the wind outside shake the branches of the trees. Again, the shutter bangs against the side of the house. Now who will fix it?

Who will mow the lawn? Who will change the lightbulb in the hall downstairs that she cannot reach? Who will help her bring in the groceries?

How can she think of these things?

She is glad it is night and the room is dark.

Time is much kinder at night—she has read this somewhere recently.

If she was to turn and look at the clock on the bedside table, she would know the time—ten, eleven, twelve o’clock or already the next day? But she does not want to look. Instead, if she could, she would reverse the time. Have it be yesterday, last week, years ago.

In Paris, in a café on the corner of boulevard Saint-Germain and rue du Bac. She can picture it exactly. It is not yet spring, still cold, but already the tables are out on the sidewalk so that the pedestrians have to step out into the street. It is Saturday and crowded. The chestnut trees have not yet begun to bloom, a few green shoots on the branches give out a hopeful sign.

She remembers what she is wearing. A man’s leather bomber jacket she has bought secondhand at an outdoor flea market, a yellow silk scarf, boots. At the time, she thinks she looks French and chic. Perhaps she does. In any event, he thinks she is French.

Vous permettez? he asks, pointing to the empty chair at her table.

She is drinking a café crème and reading a French book, Tropismes by Nathalie Sarraute.

Je vous en prie, she says, without looking up at him.

She works at an art gallery a few blocks away on rue Jacques-Callot. The gallery primarily shows avant-garde American painters. The French like them and buy their work. Presently, the gallery is exhibiting a Californian artist whose work she admires. The artist is older, well-known, wealthy; he has invited Nina to the hôtel particulier on the Right Bank where he is staying. He has told her to bring her bathing suit—she remembers it still: a blue-and-white checked cotton two-piece. The pool is located on the top floor of the hôtel particulier and is paneled in dark wood, like one in an old-fashioned ocean liner; instead of windows there are portholes. She follows the artist into the pool and as she swims, she looks out onto the Paris rooftops and since night is falling, watches the lights come on. Floating on her back, she also watches the beam at the top of the Eiffel Tower protectively circle the city. Afterward, they put on thick white robes and sit side by side on chaise longues as if they are, in fact, on board a ship, crossing the Atlantic. They even drink something—a Kir royal. She slept with him once more but they did not go swimming again. Before he leaves Paris, he gives her one of his drawings, a small cartoonlike pastel of a ship, its prow shaped like the head of a dog. Framed, the drawing hangs downstairs in the front hall.

Philip begins by speaking to her about Nathalie Sarraute. He claims to know a member of her family who is distantly related to him by marriage.

At the time, she does not believe him.

A line, she thinks.

She hears the phone ring downstairs. As a precaution, she has turned it off in the bedroom—why, she wonders? So as not to wake him? She reaches for the receiver but the phone abruptly stops midring. Just as well. She will wait until morning. In the morning she will make telephone calls, she will write e-mails, make arrangements; the death certificate, the funeral home, the church service—whatever needs to be done. Tonight—tonight, she wants nothing.

She wants to be alone.

Alone with Philip.

She is not religious.

She does not believe in an afterlife, in the transmigration of souls, in reincarnation, in any of it.

But he does.

I don’t believe in reincarnation and that other stuff and I don’t go to church but I do believe in a God, he tells her.

Where were they then?

Walking hand in hand along the quays at night, they stop a moment to look across at Nôtre-Dame.

Mathematicians, I thought, weren’t supposed to believe in God, she says.

Mathematicians don’t necessarily rule out the idea of God, Philip answers. And, for some, the idea of God may be more abstract than the conventional God of Christianity.

At her feet, the river runs black and fast, and she shivers a little inside her leather bomber jacket.

Like Pascal, Philip continues, I believe it is safer to believe that God exists than to believe He does not exist. Heads God exists and I win and go to heaven, Philip motions with his arm as if tossing a coin up in the air, tails God does not exist and I lose nothing.

It’s a bet, she says, frowning. Your belief is based on the wrong reasons and not on genuine faith.

Not at all, Philip answers, my belief is based on the fact that reason is useless for determining whether there is a God. Otherwise, the bet would be off.

Then, leaning down, he kisses her.

His eyes shut, Philip lies on his back. His head rests on the pillow and she has pulled the red-and-white diamond-patterned quilt up to cover him. He could be sleeping. The room is tidy and familiar, dominated by the carved mahogany four-poster. Opposite it, two chairs, her beige cashmere sweater hanging on the back of one; in between the chairs stands a maple bureau whose top is covered with a row of family photos in silver frames—Louise as a baby, Louise, age nine or ten, as the Black Swan in her school production of Swan Lake, Louise holding her dog, Mix, Louise dressed in a cap and gown, Louise and Philip sailing, Louise, Philip, and Nina horseback riding at a dude ranch in Montana, Louise and Nina skiing in Utah. Also on top of the bureau is a lacquer box where she keeps some of her jewelry. Her valuable jewelry—a diamond pin in the shape of a flower, a three-strand pearl necklace, a ruby signet ring—is inside the combination safe in the hall closet. Closing her eyes, she tries to remember the combination: three turns to the left to 17, two turns to the right to 4, and one turn to the left to 11 or is it the other way around? In any case she can never get the safe open; Philip has to. And, next to the lacquer jewelry box, the blue-and-green clay bowl Louise made for them in third grade in which, each evening, Philip places his loose change. The closet doors are shut and only the bathroom door is ajar.

When is a door not a door? When it is a . . .

Stop.

Perhaps she should put on her nightgown and lie down next to him and in the morning, when he wakes up he will reach for her the way he does. He will hike up her nightgown. Take it off, he will say. He likes to make love in the morning. Sleepy, she takes longer to respond.

She has not bothered to draw the curtains. Outside, above the waving tree branches, she can make out a few stars in the night sky. A mere dozen in a galaxy of a billion or a trillion stars. Perhaps death, she thinks, is like one of those stars—a star that can be seen only backward in time and exists in an unobservable state. While life, she has heard said, was created from stars—the stars’ debris.

What did he say to her exactly?

I am a bit tired, I am going to lie down for a minute before supper.

or

I am going to lie down for a minute before supper, I am a bit tired.

or something else entirely.

She is in the kitchen. Spinning the lettuce. She looks up briefly.

How was your day?

She half listens to his reply.

We had a faculty meeting. You should hear how those new physicists talk! They’re crazy, Philip says, as he goes upstairs.

She makes the salad dressing, she sets the table. She takes the chicken out of the oven. She boils new potatoes. Then she calls him.

Philip! Dinner is ready.

She starts to open a bottle of red wine but the cork is stuck. He will fix it.

Again, Philip, Philip! Dinner!

Before she walks into the bedroom, she knows already.

She sees his stocking feet. He has taken off his shoes.

What was he thinking? About dinner? About her? A paper he is reading by one of his students, arguing that Kronecker was right to claim that the Aristotelian exclusion of completed infinites could be maintained?

Infinites. Infinite sets. Infinite series.

Infinity makes her anxious.

It gives her nightmares. As a child, she had a recurring dream. A dream she can never put into words. The closest she comes to describing the dream, she tells Philip, is to say that it has to do with numbers. The numbers—if in fact they are numbers—always start out small and manageable, although in the dream Nina knows that this is temporary, for soon they start to gather force and multiply; they become large and uncontrollable. They form an abyss. A black hole of numbers.

You’re in good company, is what Philip tells her. The Greeks, Aristotle, Archimedes, Pascal all had it.

The dream?

No, what the dream stands for.

Which is?

The terror of the infinite.

But, for Philip, infinity is a demented concept.

Infinity, he says, is absurd.

“Suppose, one dark night,” is how Philip always begins his undergraduate course on probability theory, “you are walking down an empty street and suddenly you see a man wearing a ski mask carrying a suitcase emerge from a jewelry store—the window of the jewelry store, you will have noticed, is smashed. You will no doubt assume that the man is a burglar and that he has just robbed the jewelry store but you may, of course, be dead wrong.”

Philip is a popular teacher. His students like him. The women in particular, Nina cannot fail to notice.

He is so sanguine, so merry, so handsome.

Vous permettez?

He is so polite.

Too polite, she sometimes reproaches him.

They do not go to bed with each other right away. Instead he questions her about the well-known American painter.

I don’t want you to sleep with anyone else but me, he says. He sounds quite fierce. They are standing on the corner of boulevard Saint-Germain and rue de Saint-Simon, near the apartment where he is staying with his widowed aunt. A French aunt—or nearly French. She married a Frenchman and has lived in France for forty years. Tante Thea is more French than the French. She talks about politics and about food; she is impeccably dressed and perfectly coiffed; she serves three-course lunches, plays golf at an exclusive club in Neuilly, goes to the country every weekend. She refers to Philip as mon petit Philippe and, over time, Nina grows to like her.

A hot Saturday afternoon, the apartment will be empty. Across the boulevard, a policeman stands guarding a ministry. A flag droops over the closed entryway. Cars go by, a bus, several noisy motorcycles. They stand together not saying a word.

Come, Philip finally says.

Mon petit Philippe.

Nina smiles to herself, remembering.

He is so tentative, so determined to please her.

“The assumption that the man in the ski mask has robbed the jewelry store is an example of plausible reasoning but we, in this class”—is how Philip continues his lecture—“will be studying deductive reasoning. We will look at how intuitive judgments are replaced by definite theorems—and that the man robbing the jewelry store is in fact the owner of the jewelry store and he is on his way to a costume party, therefore the ski mask, and the neighbor’s kid has accidentally thrown a baseball through his store window.

“Any questions?”

Most probably a sudden cardiac arrest—not a heart attack—their neighbor, an endocrinologist, says. He tries to explain the difference to her. A heart attack is when a blockage in a blood vessel interrupts the flow of blood to the heart, while a cardiac arrest results from an abrupt loss of heart function. Most of the cardiac arrests that lead to sudden death occur when the electrical impulses in the heart become rapid or chaotic. This irregular heart rhythm causes the heart to suddenly stop beating. Some cardiac arrests are due to extreme slowing of the heart. This is called bradycardia.

Did he say all of that?

No, no, Philip has never been diagnosed with heart disease. Philip is as healthy as a horse. He had a physical a few months ago. That is what his doctor said. In any case it is what Philip told her his doctor said.

No, no, Philip does not take any medication.

Their neighbor, Hugh, looks for a pulse. He puts both hands on Philip’s heart and applies pressure. He counts out loud—one, two, three, four—until thirty.

Nina tries to count out loud with him—nineteen, twenty, twenty-one . . .

She has trouble making a sound above a whisper.

Poor Hugh, he does not know what to say—something about a defibrillator only it is too late. His dinner napkin is still hanging from his belt and he only notices it now. Blushing slightly, he pulls it off.

No. He must not call anyone.

Nina ran next door to fetch him just as he and his wife, Nell, are sitting down to their supper in the kitchen. Their dog, an old yellow Lab, stands up and begins to bark at her; upstairs, a child starts to cry. They have two children, one a month old. A girl named Justine. A day or two after Nell came home from the hospital, Nina went over with a lasagna casserole and a pink sweater and matching cap for the baby. How long ago that seems.

Hugh says, Call us any time. Nell and I . . . His voice trails off.

Yes.

Yes, yes, I will.

And call your physician. He’ll have to draw up the death certificate.

Yes, in the morning, I will.

Will you be all right . . . ? Again, his voice trails off.

Yes, yes. I want to be alone.

Thank you.

Thank you, she says again.

She hears the front door shut.

Bradycardia.

The name reminds her of a flower. A tall blue flower.

Iris.

An old-fashioned name.

The name of the woman killed in the car accident. She must have been pretty, Nina imagines. Slender, blonde. Both are young—Iris is only eighteen and he is driving her home after a party, it is raining hard—perhaps Philip has had one drink too many but he is not drunk. No. Around a curve, he loses control of the car—perhaps the car skids, he does not remember; nor did he when the police question him. They hit a telephone pole. Iris is killed instantly. He, on the other hand, is unhurt.

Nina wonders how often Philip still thinks about Iris. Did he think of her before he died? Did he think he might have had a happier life had he married her? In a way, Nina envies Iris. Iris has remained forever young and pretty in his mind while he has only to glance at her and see how Nina’s skin is wrinkled, her hair, once auburn or red—depending on the light—is gray, her breasts have lost their firmness.

Philip spoke of the accident on their honeymoon, on their way to Puerto Vallarta.

I just want you to know that this happened to me is what he says.

It happened also to Iris is what Nina wants to say but does not.

It took me a long time to get over it and come to terms with it is what he also says.

How did you come to terms with it? Nina wants to ask.

It was a terrible thing.

Yes.

Now, I don’t want to think about it anymore, he says.

And I don’t want to talk about it anymore. Do you understand, Nina?

Nina said she does but she doesn’t.

What was she like? Iris? she nonetheless asks. She tries to sound respectful. Was she Southern? Iris is such an unusual name.

She was a musician, Philip answers.

Oh. What did she play? The piano?

But Philip does not answer.

When she first arrived in Paris, at the airport, she sees a man, in the immigration line ahead of her, take off his wedding ring and pin it to the lining of his attaché case with a safety pin that he must keep there for that purpose.

What about your wife? she wants to shout.

Sometimes, in her mind, she accuses Philip of losing his wedding ring on purpose.

Her throat is dry; she finds it hard to swallow.

Downstairs, the lights are on. She goes to the hall closet, which is full of coats. Hers, his—a navy blue wool coat, a parka, a down jacket, a raincoat, an old windbreaker. The windbreaker must be twenty-five years old. She remembers how proud Philip was when he bought it. The windbreaker was bright yellow and on sale and, he claimed, would last him a lifetime. He is right. Now the windbreaker is faded, the collar and cuffs are frayed, without thinking about it, she takes it out of the closet and puts it on. Carefully, she zips it up. Her hands go to the pockets. Slips of paper—bills, a to-do list: car inspection, call George about leak in basement, bank, pick up tickets for concert. The list, she recognizes, is several months old; coins, paper clips, a ticket stub are in the other pocket.

She walks into the dining room. The chicken, the new potatoes, the salad are all on the table. Cold, waiting. Nina starts to pick up a dish to put it away and changes her mind. Tomorrow, she thinks. Tomorrow she will have plenty of time to put things away, to do the dishes, to do—she cannot think what. Instead, she takes the bottle of wine with the cork stuck inside it. Again, she tries to pull the cork out but can’t. Damn, she says to herself. She goes to the kitchen and gets a knife. With the handle of the knife, she pushes the cork inside the bottle and pours herself a glass of wine.

Still holding the knife, a sharp kitchen knife, she makes a motion with it as if to slit her throat. Catching a glimpse of her reflection in the dining room mirror, she shakes her head.

What would Louise think?

Holding the glass of wine, she goes back upstairs.

Outside, the sound of a police car siren. From the bedroom window, she sees a blue light flash by in the dark, then rush past the house and disappear. She thinks of the car full of teenagers playing loud music and she imagines it smashed into a tree, the windshield bits of glittering glass as smoke rises from the hood and someone in the backseat screams.

Another siren. Another police car goes by.

Poor Iris, she says to Philip.

Again, the phone rings.

Louise.

Earlier, she left Louise a message. Louise, darling, something has happened. Call me as soon as you can.

Poor Louise.

Philip’s darling.

A beautiful, lively, headstrong young woman who looks like him—tall, dark, with the same gray eyes. Nina must answer the phone.

Hello, she says, picking up the receiver in the bedroom.

Louise?

Whoever it is hangs up.

A wrong number. In the dark, Nina looks for a caller ID on the phone but there is none.

She is relieved. She does not want to tell Louise.

It is three hours earlier in California, and Louise, she imagines, is having dinner. She is having dinner with a young man. A handsome young man whom she likes. Afterward, Louise will not pick up her messages, she will sleep with him.

For Louise, Philip is alive still.

Lucky Louise.

Nina takes a sip of wine, then, putting down the glass, reaches for his hand again. His hand is cold and she attempts to warm it by holding it between both of hers.

She loves Philip’s hands. His long blunt fingers. Fingers that have touched her in all kinds of ways. Passionate ways about which she does not want to let herself think—making her come. She presses the hand to her lips.

When did they last make love?

A Sunday morning, a few weeks ago. The house is quiet, the curtains are drawn, and the bedroom is dark enough. She is self-conscious about being too old for sex. Also, it takes him longer.

In Paris, too, in Tante Thea’s old-fashioned, shuttered apartment on the rue de Saint-Simon, where, on the way to Philip’s bedroom, she bumps into furniture—side tables, spindly-legged chairs, glass cases filled with porcelain figurines—and where in bed, afterward, Philip admits that he was nervous. Without telling her why, he says he had not made love in a long time. He was afraid, he says, he had forgotten how.

You can never forget—like riding a bicycle, Nina adds.

This or her trite remark makes him laugh and, reassured or, at least, not as nervous, Philip makes love to her again.

Has he been faithful to her?

She reaches for the glass of wine.

Also, not thinking, Nina reaches into the windbreaker pocket and pulls out a coin. It feels like a penny.

Heads? Tails?

“The probability of an event occurring when there are only two possible outcomes is known as a binomial probability,” Philip tells his students. “Tossing a coin, which is the simple way of settling an argument or deciding between two options, is the most common example of a binomial probability. Probabilities are written as numbers between one and zero. A probability of one means that the event is certain—”

When Louise is six years old, she begins to play a game of tossing pennies with Philip. She records the results along with the dates in a little orange notebook, which she keeps in the top drawer of Philip’s bedside table:

5 heads, 10 tails — 10/10/1976

9 heads, 11 tails — 3/5/1977

17 heads, 13 tails — 2/9/1979

The more times you toss a coin, Lulu, Philip tells Louise, the closer you get to the true theoretical average of heads and tails.

5039 heads, 4961 tails — 3/5/1987

For the last entry, Louise relies on a calculator.

“Another thing to remember and most people have difficulty understanding this,” Philip continues to tell his class as he takes a penny out of his pocket and tosses it up in the air, “is if a coin has come up heads a certain number of times, it will not necessarily come up tails next, as a corrective. A chance event is not influenced by the events that have gone before it. Each toss is an independent event.”

Heads, Philip tells Louise.

Heads, again.

Heads.

Tails, he says.

Nina, on an impulse, throws the coin she found in the pocket of Philip’s windbreaker up in the air. Too dark to see which way it comes up, she places the coin on top of the bedside table. In the morning she will remember to look:

Heads is success, tails is failure

And record the date in Louise’s orange notebook: 5/5/2005.

5 5 5

What, she wonders, do those three 5s signify?

Numbers are the most primitive manifestations of archetypes. They are found inherent in nature. Particles, such as quarks and protons, know how to count—how does she know this? By eating, sleeping, breathing next to Philip. Particles may not count the way we do but they count the way a primitive shepherd might—a shepherd who may not know how to count beyond three but who can tell instantly whether his flock of, say, 140 sheep, is complete or not.

Also, she remembers the example of the innumerate shepherd and his sheep.

She drinks a little more wine. She has not eaten since noon but chewing food seems like an impossible task. A task she might have performed long ago but has forgotten how.

She would like a cigarette. She has not smoked in twenty years yet the thought of lighting it—the delicious whiff of carbon from the struck match—and inhaling the smoke deep into her lungs is soothing. She and Philip both smoked once.

In Tante Thea’s apartment, after making love for the first time, they share a cigarette, an unfiltered Gauloise. They hand it back and forth to each other as they lie on their backs, naked, on the lumpy single bed—the ashtray perched on her stomach. And later when they begin to kiss again, she remembers how Philip licks off a piece of cigarette paper stuck to her lip, and, then, how he swallows it. At the time, it seems a most intimate gesture.

As if she is exhaling smoke, Nina lets out a long deep breath.

Are you a spy? she asks. Are you employed by the CIA?

At the beginning, she makes a point to be difficult. She does not intend to be an easy conquest. She does not want to fall in love yet.

No. Yes. If that is what you want to believe.

Philip has a Fulbright scholarship and is teaching undergraduate math for a year at the École Polytechnique.

And do all the girls have a crush on you?

Alas, there aren’t many girls in my class. The few are the grinds. Philip makes a face of distaste.

There’s Mlle. Voiturier and Mlle. Epinay. They sit together and don’t say a word. They have terrible B.O.

In spite of herself, Nina laughs.

Do I? Nina makes as if to smell her underarm.

No. What perfume do you wear?

L’Heure Bleue.

Philip smells faintly of ironed shirts.

He still does.

Spring. The weather is warm, the chestnut trees are in flower, brilliant tulips bloom in the Luxembourg Garden. In the evenings, they stroll along the quays bordering the darkening Seine, watching the tourist boats go by. On one such evening, a boat shines its light on them, illuminating them as they kiss. On board, everyone claps and Philip and Nina, only slightly embarrassed, wave back.

What I was saying about whether God exists or not, Philip continues as they resume walking hand in hand, is that, according to Pascal, we are forced to gamble that He exists.

I’m not forced to gamble, Nina says, and believing in God and trying to believe in Him are not the same thing.

Right but Pascal uses the notion of expected gain to argue that one should try to lead a pious life instead of a worldly one, because if God exists one will be rewarded with eternal life.

In other words, the bet is all about personal gain, Nina says.

Yes.

On the way home, as Nina crosses the Pont Neuf, the heel of her shoe catches, breaks off. She nearly falls.

Damn, she says, I’ve ruined my shoe.

Holding on to Philip’s arm, she limps across the street.

A sign, she says.

A sign of what?

That I lead a worldly life.

Shaking his head, Philip laughs.

On a holiday weekend, they drive to the coast of Normandy. They walk the landing beaches and collect stones—in her studio, they are lined up on the windowsill along with stones from other beaches. At Colleville-sur-Mer, they make their respectful way among the rows and rows of tidy, white graves in the American cemetery.

How many?

9,387 dead.

On the way to La Cambe, the German military cemetery, it begins to rain.

Black Maltese crosses and simple dark stones with the names of the soldiers engraved on them mark the wet graves.

More than twice as many dead—according to the sign.

Why did we come here? Nina asks. And it’s raining, she says.

Instead of answering, Philip points. Look, he says.

In the distance, to the west, there is clear sky and a faint rainbow.

Make a wish, Nina says.

I have, Philip answers.

Always, on their trips, they stay in cheap hotels—neither one of them has much money. Closing her eyes, she can still visualize the rooms with the worn and faded flowered wallpaper, the sagging double bed with its stiff cotton sheets and uncomfortable bolster pillows; often there is a sink in the room and Philip pees in it; the toilet and tub are down the hall or down another flight of stairs. Invariably, too, the rooms are on the top floor, under the eaves, and if Philip stands up too quickly and forgets, he hits his head. The single window in the room looks out onto a courtyard with hanging laundry, a few pots of geranium, and a child’s old bicycle left lying on its side. The hotels smell of either cabbage or cauliflower—chou-fleur.

Chou-fleur, she repeats to herself. She likes the sound of the word.

Always, in her mind, she and Philip are in bed.

Or they are eating.

During dinner at a local restaurant, over their entrecôtes—saignante for him, à point for her—their frites, and a carafe of red wine, Philip talks about his class at the École Polytechnique, about what he is teaching—nombres premiers, nombres parfaits, nombres amiables.

Tell me what they are, she says, in between mouthfuls. She is always hungry. Starving, nearly.

I’ve told you already, he says, pouring her some wine. You weren’t listening.

Tell me again about the ones I like, the amiable ones.

Amiable numbers are a pair of numbers where the sum of the proper divisors of one number is equal to the other. 220 and 284 are the smallest pair of amiable numbers and the proper divisors of 220 are—Philip shuts his eyes—1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 11, 20, 22, 44, 55, and 110, which add up to 284, and the proper divisors of 284 are 1, 2, 4, 71, and 142, which add up to 220—do you see?

Imagine figuring that out, she says, waving a forkful of frites in the air.

Who did?

Thabit ibn Qurrah, a ninth-century Arab mathematician.

How many amiable numbers are there?

No one knows.

Then there are the perfect numbers—6 is a perfect number. The divisors of 6 are 1, 2, and 3, which add up to 6.

But she has stopped listening to him. Perfection interests her less.

Do you want dessert? she asks. The crème caramel or the tarte aux poires?

She talks to him about how, more than anything, she wants to paint. Paint like her favorite artist, Richard Diebenkorn.

His still life and figure drawings. Do you know his work?

Philip shakes his head.

I’ll show them to you one day.

They argue, but without rancor, discussing and exchanging ideas. Both are attracted by abstractions. Sometimes she forgets that she has not known Philip all her life or not known him for years.

It was a happy time and they are married in the fall.

More than 10 percent of a person’s daily thought is about the future, or so she has heard say. Out of an average of eight hours a day, a person spends at least one hour thinking about things that have not yet happened. This will not be true for her. She has no desire to think about the future. For her, the future does not exist; it is an absurd concept.

She prefers to think about the past. Yesterday, for instance? She tries to remember what she and Philip did yesterday. What they said. What they ate.

When did she last speak to Louise? On the telephone, Louise described her job with the Internet start-up—a promotion, a raise, a cause for celebration. And is she, at this very moment, celebrating at her favorite Japanese restaurant? Nina pictures Louise talking excitedly to the young man who sits across from her, and as deftly with her chopsticks, she picks up expensive raw fish and puts it in her mouth.

Three weeks before her due date, alone—Philip is at a conference in Miami—in the third-floor walk-up apartment in Somerville, Nina wakes up with contractions. Hastily, she gets dressed, collects a few things, and calls a taxi. The taxi company does not answer. She tries to time the contractions but she barely has time to recover from one before she has another. Again she tries to call the taxi company, again she gets no answer. She dials 911. For the first time, she notices that it is snowing. Snow swirls in great wind-driven whorls blanketing the parked cars, the trees, obscuring the street. Putting on her coat and picking up her bag, she starts downstairs; once her foot catches and she trips, falling down several steps. In an apartment below, a dog begins to bark and she hears someone shout, Shut up, damn it. Half afraid whoever it is will come out and find her, she holds her breath. In the front hall of their building, her water breaks, a stream hitting the cracked linoleum floor. A few moments later, she sees a car pull up and, muffled in a hat and coat, a policeman runs to the door. Rosy-faced from the cold, he looks young—younger than she. Leading her out into the snow, he holds Nina up under the arms to keep her from slipping in her flimsy leather moccasins—the only shoes that still fit, so swollen has all of her become—as they make their way to the car.

She lies down in the back of the police car, a grille separating her, like a criminal, from the back of the head and shoulders of the young policeman who is driving. The streets are unplowed and covered in several inches of new snow and she is aware of the eerie reflection of the car’s blue light, illuminating her in surreal-like flashes. The policeman speaks to someone on his radio; ten-four, he repeats, as he drives; when he has to use the brake, the car skids sideways. A truck with chains rumbles noisily past them in the opposite direction and Nina, momentarily caught in the truck’s headlights, has a glimpse of the driver’s surprised stare. Louise is almost there.

What, she wonders, does the young man in the restaurant with Louise look like?

Does he look like Philip?

Philip has an eidetic memory. He has total recall of names, places, and nearly every meal he has eaten—the good ones, in particular. He can quote entire passages from books and recite poems by heart: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner; Paradise Lost; Shakespeare’s speeches: Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this son of York—she hears his voice taking on a sonorous tone along with a British accent. He can recite lengthy bits in Latin that he learned as a young boy.

A trick, he claims. One has to make an association between the words and a visual image that one positions in space. The Greeks knew how to do this. The story of Simonides is the classic example.

You told me once but I’ve forgotten it, Nina says.

Simonides was hired to recite a poem at a banquet but when he finished, his host, a nobleman, refused to pay him as he had promised, complaining that instead of praising him in the poem, Simonides praised Castor and Pollux and he should ask the two gods to pay him. Simonides was then told that two men were waiting for him outside and he left the banquet hall but when he got outside—

I remember now, Nina says. No one was there but the roof of the banquet hall collapsed, killing everyone. The corpses of the guests were so mangled that they were unrecognizable but since Simonides had a visual memory of where each had been sitting, he could identify them. I remember you told me that story on Belle-Île, one summer. We were in a café next to the harbor. I think we were waiting for the ferry and for Louise.

That’s my point exactly, Philip says, smiling.

Closing her eyes, she can see the house on Belle-Île. A colorful, old house, one side is painted red; the shutters, too, are red, a deeper, darker red. The plaster walls are a foot thick and the ceilings are low. Blue hydrangeas grow in dense hedges all around the house.

The house looks like the French flag, Philip says.

From Quiberon, they take the ferry. Often the sea is rough and the boat pitches and rolls, sending spray high up to splash the cabin windows where the passengers sit, blotting out the island as it grows closer. One time, Nina watches a farmer try to drive his horse and wagon on the boat and the horse, his hooves clattering noisily and drawing sparks, refuses at first to step onto the metal ramp. It is low tide and the grade is steep and the horse rears and nearly breaks his harness. He is a big white farm horse and during the entire voyage to Belle-Île, Nina hears him whinnying from below deck.

For close to twenty years, they rent the same house. The house belongs to a local couple, who slowly, slowly, over the years, renovate and modernize it, so that each summer there is something new—a stove, a fridge, an indoor toilet, curtains. Even in bad weather when they are forced to stay indoors, it makes little difference to Philip and Nina. Life on the island is simple, food is plentiful: oysters, langouste, all kinds of fish; every morning, in town, there is a market. Nina buys vegetables, bread, the local cheese—a goat cheese, with an acrid gamy taste. She and Philip swim, sit in the sun, read; one summer they read all of Proust in French: Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure. Parfois, à peine ma bougie éteinte, mes yeux se fermaient si vite que je n’avais pas le temps de me dire “Je m’endors.”—Philip can recite several more pages by heart. In the afternoon when the wind picks up, he goes sailing and she paints—or tries to.

Claude Monet, famously, spent a summer on Belle-Île. A framed poster of his painting of rocks off the Atlantic coast—rocks that look like prehistoric beasts sticking their pointed, dangerous heads out of the water—hangs in her studio. She has stared long and hard at both the painting and the rocks, which she, too, wants to paint. The sea, in particular. How menacing it looks in Monet’s painting and how tame and lifeless in her own. Her sea looks like soup. Eventually, she gives up and destroys it. Later, back home, she paints the same scene abstractedly. The rocks are vertical brown lines, the sea blue, green, and red horizontal stripes. The painting is almost successful.

Louise learns how to swim and ride a two-wheel bicycle on Belle-Île. A few years later, Philip teaches her how to sail.

You should see how Lulu sets the spinnaker, Philip boasts. It takes her twenty seconds. He is proud of her.

Nina has an affair on Belle-Île but she does not want to think of that.

No, not now.

The house is only a short walk from the sea. The first thing she does when she arrives each summer is to go down to the beach and swim. The cold water is a shock, but bracing, and, after the long trip, it makes Nina feel clean.

Jean-Marc.

Is this the first time you’ve crossed the Atlantic? Nina asks, when she meets him.

Solo, he has sailed in a race from Belle-Île to an island in the Caribbean, and he has won. A celebration of his victory is being held at a local restaurant.

Fair-haired, solidly built, and not tall—no taller than Nina—his eyes are a light blue, like a dog’s. A husky. Or the blue of the Caribbean. He is a bit younger than Nina.

No, no, he laughs at her. This is my ninth trip across the Atlantic.

Oh. Embarrassed, she turns away.

Standing beside him, his pretty wife, Martine, smiles up at him.

Next, Philip is asking Jean-Marc a lot of questions: What type of sails? Does he have radar? Loran? How accurate is it? Loran, she hears Philip say, suffers from the ionospheric effects of sunrise and sunset and is unreliable at night.

Navigation systems never posed a problem for me. But nature, yes, Jean-Marc answers. Nature can pose big problems. Two years ago, when I was halfway across the Atlantic, a whale attached herself to my boat. First she swam on one side of my boat, then she dove under and disappeared for a few minutes—Jean-Marc makes the motion of a whale diving with his hands—before she reappears again on the other side of my boat. She was playing with me. She continues like this for two days and two nights—I can still see the whale’s little eyes shining up at me in the dark, Jean-Marc says, shaking his head. It makes me—how you say?—complètement fou.

In French, whale is feminine, la baleine, Philip explains to Nina, imitating Jean-Marc’s accent and gestures, as he retells the story.

I know, she says.

Je sais.

Philip’s assurance always astonishes her. It is not arrogance but a confidence, based in part on old-fashioned principles and in part on intelligence, that he is right and, usually, he is. For Nina, this is both a comfort and an irritant.

Strange, too, Nina reflects for perhaps the hundredth time, how Philip, who was born and raised hundreds of miles from the sea, should have become such a keen sailor. None of his family are.

It began with rowing on the Charles, he tells Nina. Then, one day, over Memorial Day weekend, my roommate took me out sailing on his family’s boat, a thirty-three-foot ketch called the Mistral—I didn’t know the difference between port and starboard—and we sailed over to Martha’s Vineyard. The wind was just right, and I will never forget how peaceful I felt that night, lying on the deck and looking up at the stars and listening to the sound of the water against the boat’s hull. In a funny way, it was a moment—how to describe it—where I felt completely at one. At one with the world and with the universe.

Maybe you got enlightened, Nina tells him.

Not very likely, Philip answers.

Right then and there I almost changed my major from math to astronomy and I also vowed to myself that one day I, too, would own a boat.

Downstairs in the basement, there is a decrepit rowing machine and, for years now, Nina has rarely heard the whirr of it. She has begun a campaign to throw the machine out. Useless outmoded junk, she claims. A fire hazard.

Now she can throw it out.

She takes a quick, almost furtive look out the window. The night seems very dark and silent. She can no longer see any stars. What is the saying Philip likes to quote? I much prefer a bold astronomer to a decorous star. She disagrees. She prefers a star to an invention.

It must be late, she decides.

She needs to get more wine. This time she will bring the bottle back upstairs.

He won’t mind, she thinks.

“In general,” Philip might say, were he to turn her infidelity into a classroom exercise, “if we know for certain that my wife is not having an affair, the probability of the event would be 0; but, should we discover that she is having an affair, the probability would be 1. The numerical measure of probability can range from 0 to 1—from impossibility to certainty. Thus, the probability of my wife being unfaithful would be 1 over 2 because there are only the two possibilities: that she is having an affair or that she is not having an affair.”

While she and Jean-Marc are in bed one afternoon, someone knocks at the front door and calls out Nina’s name—the landlady checking on the new refrigerator or leaving her some fresh lettuce from her garden.

Un moment, Nina calls back down. J’arrive.

Only half dressed and holding his shoes in one hand, Jean-Marc climbs out the bedroom window. Jumping, he lands squarely on his feet. In another moment, he leaps over the hydrangea hedge and is gone.

Jean-Marc has the tight, muscular body of a gymnast.

“But let us take another example,” Philip continues. “The probability of a person crossing a street safely is also 1 over 2 because again there are only two possible outcomes: crossing safely and not crossing safely. Yet the trouble with this argument is that the two possible outcomes—crossing safely and getting run over—are not equally likely. If they were, people would not want to cross the street very often or if they did, a lot of them would get hurt or killed. So therein lies the fallacy. The definition given by Fermat and Pascal applies only if one can analyze the situation into equally likely possible outcomes, which takes me back to my original example—and to put your minds at ease”—a few of the students laugh—“since I know my wife to be a truthful and loving woman, she is not likely to be unfaithful and to have had an affair.”

General laughter and applause.

Trust is a word we have put too much trust in, Philip also tells his class.

Iris again.

Was Iris, like Philip, a native of Wisconsin? A blonde beauty of Scandinavian origin—her hair so blonde it is white. And a musical prodigy. Nina has read about children who learn how to play the piano at age three, compose their first piece at five, debut as a soloist at seven—was Iris one of them? She pictures her sitting, small and demure, a bow in her hair, on the piano bench in front of the Steinway grand, her feet reaching for the pedals as she starts to play. Her little hands move swiftly and assuredly; the sound she makes is passionate. She plays Philip’s favorite Chopin polonaise—Nina can hear the melody in her head—which promises redemption and celebrates Polish heroism. Were they high school sweethearts and did they sleep together? Perhaps Iris is pregnant and she has just found out. Twice she has missed her period and every morning now she throws up her breakfast. She has screwed up her courage to tell Philip in the car on the way home from the party. The reason he drives off the road.

Nina leans over Philip. Lightly, she touches his cheek. How can this have happened? How can this be?

Philip is so robust, so healthy, so—she tries to think of the right words—so engaged in life.

Come back, she whispers. Please, come back.

How can he leave her?

Without saying good-bye.

Without a word.

Please, she pleads.

Putting her head down on his chest, she listens.

At home, some evenings, Philip likes to play music and take her in his arms and whirl her in a quick two-step to La vie en rose, down the front hall, past the umbrella stand, the closet full of coats and past the pastel of a ship, its prow shaped like the head of a dog.

The top of her head reaches his collarbone, she can feel his heart beating.

His shoes are on the floor next to the bed. Old-fashioned, scuffed-up, lace-up brown oxfords. One shoe is lying on its side. Abandoned. Should she pick up the shoes and put them away in the closet? No, she will leave them there.

She picks up after Philip. It annoys her—no, worse: it angers her. His socks, his underwear, left lying around for her to put away, to hang up, to throw in the laundry basket. At first, she scolds but then bored by her own aggrieved tone and the futility of her words, she stops.

Untidiness in a man, she has read somewhere, is a sign of his having had a mother who dotes and spoils her son. Not so, in Philip’s case.

Alice, Philip’s mother, lives twenty miles away in a nursing home. The last time Nina and Philip visit her, Alice is not certain who they are. Unfailingly polite, she speaks about people Nina has never heard of: Rick who built a fireplace made out of bricks—Rick rhymes with brick—nonsense. Nina lets her mind wander. She has brought tulips from the garden, which pleases Philip’s mother.

I’ve always loved bougainvillea, she tells Nina.

Tulips, Mother, Philip tries to correct her. Tulips from our garden.

Francis, my husband, loved bougainvillea, Alice continues. Our garden in Ouro Prêto was full of bougainvillea.