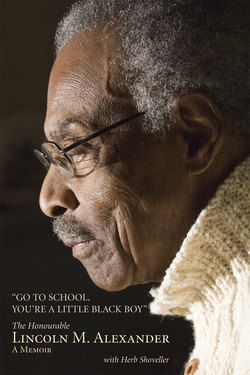

Читать книгу Go to School, You're a Little Black Boy - Lincoln Alexander - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 3

ОглавлениеThe Call of Higher Learning

After I settled into my university studies, I arranged for my mother to return to Canada from New York. She was quite a classy person, and one of the best examples of that is the fact that I can’t recall her ever putting down or insulting my father, despite the fact he had cheated on her in the worst way and was the cause of the disintegration of their marriage. I had experienced the impact of his indiscretion, too. I watched the pain and suffering and indignities my mother faced. I ended up having almost no connection to my kid brother. I swore that I would never let such a thing happen in my marriage. I could see how it could destroy a family.

There was a good deal of pain still ahead. My mom started suffering pre-senile dementia shortly after coming to Hamilton, and she slowly began losing track of everything, including the people around her. Once another patient in the hospital came to me and said, “Do you really want to know what your mother looks like?” She lifted the covers to reveal my mother was now barely skin and bones. It was shocking to see her wasting away and covered in bruises and bedsores. It was with so much optimism that my mom and I were originally reunited in Hamilton, but unfortunately there was little joy to share after her return.

On one occasion, I went to see her and she screamed at me, “Get away from me. You are not getting into my bed tonight. Get away from me. Get away.” I was shocked and for a moment couldn’t figure out what was going on. She had never talked to me like that. Then I realized she had confused me with my dad. The incident made me realize the depth her illness and her suffering and the hurt that she had endured and held inside all those years.

In time, the hospital contacted me to tell me she had died, and I was deeply hurt, but not surprised, at the news. I was relieved that her suffering had been eased. My mother died in the Hamilton Psychiatric Hospital on my twenty-sixth birthday, January 21, 1948. She was not yet fortynine years old.

My brother Hughie, along with my mother and Hughie’s first wife, Lil Allen. Hughie was married three times.

When I look back now and see what she had to go through, courageously leaving her marriage and setting out on her own, it amazes me. She’s been my source of strength, of confidence. In a 1988 research paper by Edsel Shreve and Darren Jack at the University of Western Ontario, when I was lieutenant-governor, I described my mother this way: “She was the one that encouraged me to go to school. She was the one that indicated to me that being black you had to excel and reach for excellence at all times; you had to be two or three times as good. I’ve never forgotten that trait, especially with respect to school. I accepted what she said and as a result of that I graduated from McMaster, I became a lawyer and all of that has helped me to reach this position. To try my best to play a role in the community in several ways … but basically it has been my mother who put the seed in my mind about education.”

My dad’s later years were equally grim. For the longest time, he remained bitter over the breakup of our family, actually blaming my mother for what he called “the Alexander family troubles.” While I was prepared to fight for him — as in the time I went after Wilfred the boxer with a switchblade — I can’t say my father and I were very close. He and I got on as well as could be expected, given the circumstances, and I know he was proud of me when I was in the air force. That source of pride was twofold — first, that I was in such a highly respected uniform, and second, that I advanced through the ranks to become a corporal. In my service of Queen and country, as far as he was concerned, I had done the Alexander name proud.

I paid a visit to my mother’s gravesite shortly after she passed away. We were very close.

His pride in the Alexander name was bolstered again when I headed off to McMaster, and when I graduated, he attended my convocation. He appreciated how rare it was for a young black man at that time to achieve a university education. Regardless of our difficulties in the past, I felt we had begun to make strides in rebuilding our relationship. Then, as happened with my mother, he didn’t stick around.

He had finally cut through his walls of denial and admitted he was to blame for his marriage ending. I think the realization of this, the coming to grips with that truth, was just too much for him to bear. He had kept a lot of his own suffering inside over the years after my mom’s departure, and it had left him mentally unstable. When he went to her funeral and realized she was dead — that was when, finally, like a slap in the face, he came to terms with his guilt. After that, he could never overcome it. In despair, he took his own life. He hanged himself with his belt in the old asylum at 999 Queen Street West in Toronto a week before Christmas 1951. He was fifty-nine years old.

Truth be told, I always realized in the back of my mind that suicide was a possibility for him. Once, I came home when he wasn’t expecting me and as I came up the stairs I saw him standing in front of the bathroom mirror with a razor blade in one hand and his penis in the other. I screamed,“Dad, Dad, stop!” He was holding the blade to his penis, I assumed, because that was the thing that got him into trouble in the first place. I was afraid of him after that because I was never sure he wouldn’t use the blade on me.

Another time, as I was returning from classes at Osgoode Hall law school, there were a lot of people and police milling about outside our apartment. My father had tried to gas himself, but someone had discovered him before it was too late. One thing that really upset me that day was the doctor who was on the scene. He refused to treat my dad until I paid him five dollars, which was not easy for us to come up with at the time.

A rare picture of me with my dad, Big Alex. As usual, we were dressed to the nines.

So my dad had tried several times to take his life before he was finally successful and hung himself with a belt. I recall going to identify his body, and there was a deep black cut and bruise across his throat. It was chilling.

The fact both my parents died so young was troubling for me for some time because I worried I would die young, too. But I spent about thirty years on this Earth with them and, fortunately, I have lots of good memories.

I eventually learned I had a half-brother, Ridley “Bunny” Wright, born to my mother before she married my dad. He was about two years older than me. In our early years, we had little contact. My mother told me the barest details about the situation. She never talked about the circumstances of Ridley’s birth. Ridley stayed with an aunt in Toronto because my dad refused to accept him and would never let him live under our roof. My mother brought Ridley to New York, and he was working and living with her when I joined her there. He moved out shortly after I arrived. I used to get very angry and frustrated with him. What upset me most is that he would come home with his paycheque and brag about all the girls and money he had, and then he’d give me a measly ten cents.

He came back to Toronto in due course, married, and adopted a son, Larry. I went to his house for dinner a few times. I had better contact with my kid brother, Hughie — although it was a distant relationship with little warmth. I used to envy the families who could have everyone together for Christmas and Easter, while mine was scattered here, there, and everywhere. That used to really bother me. It was all a hell of a mess. But I came out of it.

Among some of my long-standing friends in this life would be Alfonso Allen and his wife, Ona. This friendship dates to my early days in Hamilton. Along with Alfonso and Ona I socialized with Alfonso’s brother Cleve and Enid Allen and Ray and Vivienne Lewis. One of the first places I lived when I first moved to Hamilton after the war was with Alfonso’s mother, Rachel, and her husband, John C. Holland, the dynamic preacher at Stewart Memorial Church.

This was a fortuitous connection for me because, along with providing for a lifelong friendship, it also helped establish a good social and spiritual network, and it put me back in touch with Yvonne, who was involved with the church.

Ona was originally from the community of North Buxton, near Chatham in southwestern Ontario. The village is an important location and symbol for the black community in much of Canada because it was for many blacks the last stop on the Underground Railroad and a haven for fugitives of pre-Civil War slavery in the U.S. In fact, as chairman of the Ontario Heritage Trust, I will be visiting the community in the summer of 2006 to commemorate the existence of Uncle Tom’s cabin.

Through the 1950s and my early career in law, I was active in the church and it gave me the opportunity to sing in the choir and participate in other singing activities organized through the church. Eventually that singing and church activity started to ease as my political career began to take off, but the friendships endured, as did my support for the church.

In the meantime, I was able to move ahead with my own life, personally and professionally. When I returned to Hamilton, I enrolled at Central Collegiate to finish high school. Many of us had been away from school for a long time, thanks to the war. We were placed in the “rehab” school on the third floor to top up our education. It was there, quite fortuitously, I met John Millar (whom I affectionately called Jack, or Jackie), who would turn out to be the most incredible and supportive friend for life and, in time, a partner in law. Along with Jack, I became good friends with Gary Lautens, a fellow student at the time who went on to become a popular columnist for the Toronto Star.

Central Collegiate was a classic school in the city centre, which might explain why it attracted a lot of war veterans like me. While I intended to go to university, it was not automatic that I would get in. Fortunately, I was successful in my classes, and in 1946 I was off to post-secondary education. McMaster in the city’s west end was my university of choice, as well as Jack’s, and my veteran’s allowance made it possible for me to attend.

McMaster University in 1946 was another scholastic institution then experiencing the effects of returning veterans. Most were extremely conscientious and, because of their recent war experience, they were more attuned than many regular students to political and world events, which made for a vibrant intellectual atmosphere. Along with classroom sessions, there were organizations such as the politics club, which focused on issues that were important to the post-war world. It was a fascinating environment to immerse myself in.

My high school upgrading marks report, June 1946.

My high school upgrading marks report, August 1946.

Jack and I both studied history and political economics, which provided us with a perspective on post-war problems that was useful in our later careers. Frankly, I ended up taking political economics because I thought it would be easy. Both of us graduated in 1949, and the McMaster Marmor yearbook noted Jack had entered McMaster “with the intention of future study in the field of law,” so it wasn’t surprising when he enrolled at Osgoode Hall that same year.

At Mac, I ended up on the university football team. Now, a cynic might say I was recruited because, with my height and size, I could be a potent receiver, tight end, or even a lineman. Wrong on all counts. In football, I’ve always been enamoured with running backs, so at Mac I was a spinning fullback. It’s a great position, and I imagined I could make great things happen lugging the ball for the burgundy crew. There was just one minor problem. Well, actually, major. You see, I hated taking a hit — which, in a great understatement, is a serious drawback for a fullback. Not only was I averse to getting drilled, it turned out my running style ensured I would be nailed harder and more often than other ball carriers.

The venerable Fred “Smut” Veale was our coach. He would harp at me over and over in practices and during games that when I was running I had to stay low to the ground and keep my head down. But I kept running upright, straight up and down, almost standing up, and by doing that, and being so tall, I used to get pounded. He’d say, “Get low, get low,” but I never could make the adjustment. Not surprisingly, it was hard to miss this six-foot-three giant coming through the line standing straight up. And Smut was right. By staying low you are better able to keep your balance when you get hit because you have a lower centre of gravity. Instead, I was like a tackling dummy, emphasis on the dummy.

I think if I were playing today, with the game having changed as much as it has, I would be a wide receiver or tight end. Maybe tight end in particular, because I also weighed close to 250 pounds back then. Looking back, I imagine I would have preferred a receiver position, since you wouldn’t have as much contact, but back then, the whole game was run, run, run. Then I got married and decided I couldn’t play anymore, so I told the coach my wife wanted me to study and that was part of the truth. But it was the fear of contact that actually prompted that decision. When you play competitive sports, you have to have a killer instinct, and I didn’t have that. You can’t be afraid of hitting hard, and I was afraid to get hurt.

The year I played was 1947, and our team went without a win, 0–1 in exhibition play and 0–6–0 in the regular season, finishing fourth. Under Smut, McMaster had won the Shaw Cup (Canadian Interuniversity Football Rugby Union), symbolic of the Intermediate Western Group championship, in both 1933 and 1934. Then he returned in 1946 and 1947. But his overall record was 7–18–1, and I’m sure my upright running style was no help in avoiding those numbers.

During my Mac days, dean of men Les Prince was remarkable to a bunch of us students. He took us under his wing and had a huge role in making our university days special and memorable. In my case, he did me a great favour during my less-than-distinguished experiment with football. Somehow, after scouring stores and other sources, he turned up a pair of extra-large football shoes for me. These were almost impossible to find, and he went the extra mile; I only wish I could have filled them in a way that would have better rewarded his kindness. Oh, well, at least he knew I tried. It wasn’t the only time Les helped me out with my water-ski feet. Early on, even before the football shoe hunt, he had encouraged me to get active in general athletics at Mac. I tried to beg off and visited him in his office to confess that it was impossible to find sneakers, so I would have to pass. But he said, “Look, young man, when it’s warm outside you can go barefoot, and then when it’s cold and we are indoors you can wear socks. You can find socks, can’t you? The physical activity is important for you, and it’s good for making friends.” It was sage advice that I took, and, as usual, he was right.

After I graduated from McMaster, I was intent on joining the whitecollar workforce at Stelco in Hamilton. But that was 1949 and I again came face-to-face with racism. During summers while at university, I had worked in the open hearth at Stelco. Along with dozens of other Mac grads like me, I believed I had an advantage as a war veteran and a university graduate, and I had experience at the plant, so I applied for a job at Stelco. University graduates at that time were a relatively rare and valuable commodity. Stelco was falling all over itself to hire my fellow grads. The company was also willing to give me a job but, unlike the other grads, I was offered a position in the plant, back in the open hearth. I had applied for sales. I wanted what everybody else with a B.A. was getting. Everyone from my university assisted me, and even the city’s mayor tried to help me to change the minds of Stelco’s management, but to no avail.

The clear and unacceptable implication was that the company felt having a black in sales would harm its image. There was no room for a black among the white-collar types, university education or not. I suppose it would have been easy to take the factory job and keep my mouth shut, but my belief in education and what it could offer held firm. Largely as a result of this experience, I decided to become a lawyer and be with my friend Jack Millar.

Meanwhile, my life was changing in another important way, and so much for the better. Events were coming together that would have a profound, wonderful effect on me. These events came together through Yvonne. When I was young, I used to drink a lot. In the air force, for example, I figured I was immortal. I did everything a red-blooded young Canadian man would do — not all of it good, and a fair bit of it with the potential for causing trouble. I spent a lot of time on the dark side, smoking, drinking, and partying. It might not have seemed like the dark side at the time, but once you emerge into the light and look back, there were some things I’m not proud of. So, honestly, if I hadn’t married Yvonne, I don’t know what I would have become.

I have been fortunate to have two strong, intelligent, insightful women in my life: Yvonne and my mother. From the first moment we were together, Yvonne “Tody” Harrison became the most influential force in my life. Yvonne was the daughter of Robert Harrison and Edythe Harrison (née Lewis). Her mother and father were born in Canada, and her father was part Native Canadian. Yvonne’s father, Robert, was a railway porter and, so the story goes, whenever he returned to town, Yvonne, his sweet little girl, would go down to the station to meet him. On one of these occasions, apparently, he coined for her the affectionate name “my little toad.” Pretty soon he and Yvonne’s sisters had spun that name into Tody, and it stuck for life. Yvonne was not fond of her nickname, but it was certainly used in fondness by others.

Yvonne and her three older sisters were fourth-generation Hamilton blacks, descended from American slaves who escaped to Canada through the Underground Railroad. The Harrisons were part of a small black community of about five hundred, most of whom worked as bellhops at the posh Royal Connaught Hotel or as janitors and domestics. Yvonne’s father, as I’ve noted, was a railway porter, like my dad. Because he was half Native Canadian, he had straight black hair, and Yvonne had certain aboriginal features as well. She, too, faced discrimination throughout her life, particularly when she was younger. She graduated in secretarial training from high school but found it impossible to get work related to her education. She always handled such things with a quiet dignity that I admired and that, I think, in many ways defined her as a person.

The war had intervened after our initial meeting in 1940, and I left to join the air force. While I was away during the war, even though the other guys and I were fooling around with a lot of women, Yvonne had my heart. I always had Yvonne in the back of my mind. I wrote to her regularly, but she didn’t write much, although she saved all my letters. When I came back, I made a beeline for Hamilton and we resumed our friendship. She was five years older than I, and she didn’t want to go out with me because she thought people would laugh at her for robbing the cradle. But I knew she loved me.

I wouldn’t be here, or anywhere else for that matter, without Yvonne. I had never met such a beautiful woman. She didn’t like it, but I called her my first, my last, my everything. That’s not my line, either. Some blues singer’s. I was hopelessly attracted to her. I loved her very deeply. I treated her with respect. I had made up my mind that she was going to be my wife.

I proposed to Yvonne in a restaurant in east Hamilton in 1946. I gave her an ultimatum: she had to choose either me or her family. Her family considered me a con artist and looked down on me, but you don’t have to get very high up to look down on someone. Yvonne was very shy, and her mother had taught her not to trust men. Her mom thought I was a womanizer, but I wasn’t. I didn’t like Mrs. Harrison. She wasn’t too kind to my mother, and Yvonne had told her mother that her behaviour was not acceptable, but it took years before there was any sense of warmth from that woman. We were married on September 10, 1948, while I was still at McMaster. But even after we had been married for maybe five years, her family didn’t like having me around the house.

They all treated her father terribly. Yvonne was the only one who treated him like a human being. Her mother had planted that seed of thought that men are no good, and the other sisters adopted that attitude toward him and me. Yvonne was the kind of woman who wouldn’t buy into that stuff. She was a warm, loving person, while her mother and sisters — Juanita, Audrey, and Fern — treated Robert Harrison horribly. I used to hate it.

I didn’t break through with that family until one day when I was coming home from law school. Yvonne was working, and I wanted to see our son, Keith. Her mother and sisters were looking after him, so I went to their house and told her mother enough was enough. But they never really accepted me until I became a lawyer. Then they bragged about me. How two-faced! In the long run, I became Yvonne’s mother’s lawyer, but we were never close.

We were married at Stewart Memorial Church in Hamilton and went on our honeymoon to New York, where we stayed with my aunt Iris. My wife was very pretty, and while we were there a man began flirting with her in an elevator. Yvonne was very naive. There were two handsome men on that elevator, and I realized they were pimps. One of them said, “I wonder what the penalty is if I touch her,” and I said, “Death.” They just clammed up. I wasn’t going to put up with anything like that. I was a husband now.

We had a wonderful marriage. I’m very fortunate in that regard, because I have friends who do not have wonderful marriages. I did everything for her. I put her up on a pedestal. That’s why I was so determined to succeed with my schooling. When I enrolled in law school, I knew I had to be somebody. As a lawyer, I knew I could be my own boss.

It was with much trepidation that I headed off to law school. I had a young family, and there were the ever-present worries about how I would be treated due to my colour. Some of that concern was eased immediately at registration when a friendly fellow first-year law student, John Mills, came over and introduced himself. His gesture certainly eased my inner tension, and who could have known that short incident would launch a friendship that was celebrated early in 2006 with the fifty-third reunion of our class. In the end, John, Ed Carter, and I spent a lot of our law school years together.

Studying law was a daunting challenge, not only socially but also economically. My veteran’s benefits had been exhausted with the completion of my undergraduate degree, but I sought, and was granted, an exception to extend my benefits with the proviso that I remained in the top quarter of my class. I met this challenge and graduated from Osgoode Hall in 1953, at which time there were but a handful of blacks practising law in Ontario.

In law school, when I didn’t stay with my father, I boarded in Toronto with a woman named Mrs. Roberts, and I came home to Hamilton on weekends. Yvonne and I had no money to speak of. I worked summers, mostly at the steel company. Yvonne worked in a laundry to help support our family. What always worried and motivated me was what my wife might think if I failed. She worked so hard to put me through school.

It was a very proud day when I graduated from Osgoode Hall in 1953. Pictured with Yvonne and me are fellow student Charlie Groves and his family.

Yvonne worked until I became a lawyer and then for a while after I graduated. But when I graduated I told her I wanted her to stop working and stay at home, like other lawyers’ wives. It wasn’t all that easy to persuade her, though. At that time, most lawyers were white, and we couldn’t be assured of a future. But she eventually stopped, and from 1953 to 1958 we lived with her mother. I didn’t like being there, but it wasn’t too stressful. My room was upstairs, and I spent a lot of time up there reading and working.

My law school friend John Mills helped me to partly manage these awkward and inconvenient early marriage years of living with Yvonne’s parents. At one point, John and his wife, Helen, were moving into a newer apartment that included a fridge and stove. When I asked John what he was going to do with his fridge, he said he was selling it, so I told him I wanted to buy it. I think I gave him fifteen dollars. I got it back to Hamilton and tucked it in my mother-in-law’s basement. That made no sense to John. Why go to all the trouble to buy a fridge and haul it back to Hamilton if it’s just going to sit in a basement? I explained to him that Yvonne’s mother was all over me about getting us a place of our own and the nagging was driving me crazy. The fridge was buying me time, because it convinced her we were preparing to move. Never did use it, but I appreciated the break it gave me. It was fifteen dollars well spent.

John understood the tension between me and Yvonne’s mother and sisters. I told him of one incident that still makes him chuckle to this day. I’ve always tried to dress well and look sharp, even when I was in law school and had limited means. One Friday I was walking up the street to their house in Hamilton after being away the week in Toronto, and up pipes her mother, “Well, here comes Mr. Hotshot right now.” Now that was uncalled for. John reminds me of that lovely moniker every now and then.

I chose law as a career after deciding that self-employment made the most sense for a young black man with ambition. Denial of white-collar opportunities at the steel company and the dismissive offer of a job on the shop floor — there is nothing wrong with that work, if one so chooses, but it wasn’t what I had been trained or educated for — presented new decisions. The rejection actually strengthened my resolve to make education work for me. It turns out, coincidentally, that a similar rejection with racial undertones would lead another future partner of mine, Paul Tokiwa, to study law as well.

Early in my first year at Osgoode Hall one of those momentous occasions in life occurred. One day my dad called me and said, “You’re now the proud father of a baby boy.” It was 1949, and Keith had been born. It was a magnificent day because I suddenly realized I was now a father and family man and had to work very hard. I took the bus back to Hamilton and went into the nursery to see my new son. Then I started to cry. Keith was a pretty good-looking baby, and let’s face it, most babies are pretty ugly. I suggested the name Lincoln MacCauley Alexander III, but my wife said no. She liked the name Keith. There was a player for the Calgary Stampeders at the time named Keith Spaith, and she liked the name.

While I eventually graduated from Osgoode Hall, an incident in my last year left me convinced for a time that I would never get my diploma. Addressing 250 would-be lawyers, Dean Smalley Baker used the expression, “It was like looking for a nigger in a woodpile.” When I heard him say it, my head jerked to attention, as if someone had just slapped me across the face. Actually, my friend John Mills was sitting right beside me when Baker made that comment. You have to picture this. All of us soon-to-be lawyers were squeezed into this cramped room and, to make matters worse, we had those tiny old university desks that are connected together. John and I were literally shoulder to shoulder. It was an exercise in contortion for me just to get into the desk, let alone get comfortable enough to follow the instructors. But I had no trouble hearing Baker’s slur, and John said afterward that he could feel my shoulders tighten up when the dean made that comment.

A very special picture of Yvonne with Keith as a little boy.

Dean Baker asked the class if there were any questions, and, without thinking, I stood up and said, “The one thing I don’t understand is what does it mean to say ‘looking for a nigger in a woodpile’?”

The atmosphere grew tense immediately. In this huge class there was only one other black student, Ken Rouffe. I’d say half my classmates were with me and half were shocked at my audacity. Dean Baker replied that everyone said it. I said, “But you can’t say that because you have to show leadership. You’re in a position of authority, a leader in the community. A leader has to lead and not be using such disrespectful comments without even thinking about them.”

Then I called Yvonne and told her I had just blown it. She said she was behind me, but I was panicked for the rest of the year because I was sure he was going to fail me.

Back then, you discovered if you had passed by waiting to read the published results in the Globe and Mail. When the day came, I cautiously opened to the appropriate page, and there it was — my name near the top of the class.

When I met Dean Baker at a party at the end of the school year, he was offended when I told him I was surprised I had passed. In effect, I was questioning his academic integrity by suggesting that a student could be failed if he crossed his instructor. “How can you say that?” he shot back at me, clearly perturbed. “There was never any doubt in my mind that you would pass. You are in the top quarter of the class, for goodness’ sake.”

It was a good lesson in the difference between being black in a white world and being a member of that majority. As a black, I was so suspicious of the fragility of my rights that it seemed perfectly logical I could be failed for my impertinence. To him, his academic integrity and independence were unassailable, yet he could make a comment in class like that without grasping its impact. The episode reinforced for me — and I hope served to illustrate for at least some of the other students in that class — that racism was so deeply ingrained that even people who should know better would issue such phrases with the same ease with which they would order a cup of coffee. Imagine, the dean of the country’s leading law school talking like that. And, in truth, I don’t believe there was any malicious intent. It was simply so ingrained that people didn’t even realize how wrong and hurtful it could be.

To me, an episode such as this one cuts far deeper than the comment itself. Imagine how often at that time black people bore the hurts of such comments and endured that pain in silence for fear of reprisals or punishment. Already greatly marginalized, they could be left in dire straits for fighting back. So they suffered in silence. It just so happened — whether because of my size or my courage or, some may say, my stubbornness — that I couldn’t let such comments go without responding. I was always ready to defend myself, whether physically or, as I came to deal with more thoughtfully mature people, intellectually.

Every now and then I still dream that I didn’t pass law school, a recurring nightmare not unlike the three hooded figures I talked about at the start of the book. These dreams keep me in line. But in any case, thanks to that confrontation, I’m convinced I influenced some attitudes in that law class. Whether it was the years in Harlem or the years in the air force or something else, I had a grounded understanding of what it meant to live in a white man’s world. But I was not then, nor have I ever been, a token. Nobody can intimidate me.