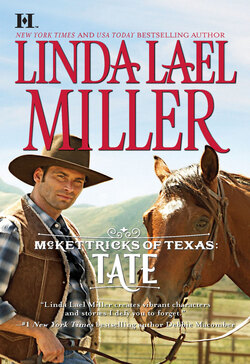

Читать книгу McKettricks of Texas: Tate - Linda Lael Miller - Страница 10

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеBY THE TIME they got to the ranch, Audrey and Ava were streaked pale orange from the smoothie spills and had developed dispositions too reminiscent of their mother’s for Tate’s comfort. The minute he brought the truck to a stop alongside the barn, they were out of their buckles and car seats and hitting the ground like storm troopers on a mission, pretty much set on pitching a catfight, right there in the dirt.

Tate stepped between them before the small fists started flying and loudly cleared his throat. The eldest of three brothers, he’d had some practice at keeping the peace—though he’d been an instigator now and again himself. “One punch,” he warned, “just one, and nobody rides horseback or uses the pool for the whole time you’re here.”

“What about kicks?” Audrey demanded, knuckles resting on her nonexistent hips. “Is kicking allowed?”

Tate bit back a grin. “Kicks are as bad as punches,” he said. “Equal punishment.”

Both girls looked deflated—he guessed they had that McKettrick penchant for a good brawl. If their features and coloring hadn’t told the story, he’d have known they were his just by their tempers.

“Let’s put Bamboozle back in his stall and make sure the other horses are taken care of,” Tate said, when neither of his daughters spoke. “Then you can shower—in separate parts of the house—and we’ll hit the pool.”

“I’d rather hit Ava,” Audrey said.

Ava started for her sister, mad all over again, and once more, Tate interceded deftly. How many times had he hauled Garrett and Austin apart, in the same way, when they were kids?

“You couldn’t take me anyhow,” Audrey taunted Ava, and then she stuck out her tongue and the battle was on again. The girls skirted him and went for each other like a pair of starving cats after the same fat canary.

Tate felt as if he were trying to herd a swarm of bees back into a hive, and he might not have untangled the girls before they did each other some harm if Garrett hadn’t sprinted out of the barn and come to his aid.

He got Audrey around the waist from behind and hoisted her off her feet, and Tate did the same with Ava. And both brothers got the hell kicked out of their knees, shins and thighs before the twin-fit finally subsided.

There was a grin in Garrett’s eyes, which were the same shade of blue as Tate’s and Audrey’s and Ava’s, as he looked at his elder brother over the top of his niece’s head. “Well,” he drawled, as the twins gasped in delight at his mere presence, “this is a fine how-do-you-do. And after I drove all the way from Austin to be here, too. Why, I have half a mind to send your birthday present right back to Neiman Marcus and pretend this is just any old day of the week, nothing special.”

Simultaneously, Tate and Garrett set their separate charges back on their sandaled feet.

Audrey smoothed her crumpled sundress and her hair—females of all ages tended to preen when Garrett was around—and asked, with hard-won dignity, “What did you get us, Uncle Garrett?”

Last year, Tate remembered with a tightening along his jawline, it had been life-size porcelain dolls, custom-made by some artist in Austria, perfect replicas of the twins themselves. He was glad the things were at Cheryl’s—they gave him the creeps, staring blankly into space. He’d have sworn he’d seen them breathe.

“Why don’t you go around to the kitchen patio and find out?” Garrett suggested mysteriously. “Then you’ll know whether it’s worth behaving yourselves for or not.”

Hostilities forgotten—for the time being anyway—the girls ran squealing for the wide sidewalk that encircled the gigantic house.

Whatever Garrett had bought for Audrey and Ava, it was sure to make Tate’s offering—a croquet set from Wal-Mart—look puny and ill-thought-out by comparison.

Not that he put a lot of stock in comparison.

“I thought you were in the capital, fetching and carrying for the senator,” Tate said, taking his brother’s measure in a sidelong glance.

Garrett chuckled and slapped him—a little too hard—on one shoulder. “Sorry I missed the shindig in town,” he said, ignoring the remark about his employer. “But I managed to get here, in spite of meetings, a press conference and at least one budding scandal neatly avoided. That’s pretty good.”

Tate sucked in a breath, let it out. Jabbed at the dirt with the heel of one boot. Garrett was a generous uncle and a good brother, for the most part, but he was living the wrong kind of life for a Texas McKettrick, and he didn’t seem to know it. “I don’t know what gets into those two,” Tate said, shoving a hand through his hair. As far as he knew, he hadn’t been in smoothie-range on the ride home, but he felt sticky all over just the same.

Whoops of delight echoed from the distant patio and Esperanza, the middle-aged housekeeper who had worked in that house since their parents’ wedding day, could be heard chattering in happy Spanish.

“They’ll be fine,” Garrett said lightly. Easy for an uncle to say, not so simple for a father.

“What the hell did you get them this time?” Tate asked, starting in the direction of the hoopla. His mood was shifting again, souring a little. He kept thinking about that damn croquet set. “Thoroughbred racehorses?”

Garrett kept pace, grinning. He usually enjoyed Tate’s discomfort—unless someone else was causing it. He was no fan of Cheryl’s, that was for sure. “Now, why didn’t I think of that?”

“Garrett,” Tate warned, “I’m serious. Audrey and Ava are six years old. They have more toys than they could use in ten lifetimes, and I’m trying not to raise them like heiresses—”

“They are heiresses,” Garrett pointed out, just as, a beat late, Tate had realized he would. “Over and above their trust funds.”

“That doesn’t mean they ought to be spoiled, Garrett.”

“You’re just too damn serious about everything,” Garrett replied.

Just then, Ava ran to meet them, glasses sticky-lensed and askew, her grubby face flushed with excitement. “It’s our very own castle!” she whooped. “Esperanza says some men brought it on a flatbed truck and it took them all day to put the pieces together!”

“Christ,” Tate muttered.

“A crew will be here next week sometime, to dig the moat,” Garrett told Ava. He might have been promising her a dress for one of her dolls, the way he made it sound.

“The moat?” Tate growled. “You’re kidding, right?”

Garrett laughed. Would have given Tate another whack on the back if Tate hadn’t sidestepped him in time. “What’s a castle without a moat?”

Ava danced with excitement, as spindly legged as a spring deer. “There are turrets, Dad, and each one has a banner flying from the top. One says ‘Audrey’ and one says ‘Ava’! There are stairs and rooms and there’s even a plastic fireplace that lights up when you flip a hidden switch—”

Man, Tate thought grimly, that croquet set was going to be the clinker gift of the century. Damned if he was about to shop again, though, and he hadn’t set foot in Neiman Marcus since he was sixteen, when his mother dragged him there to pick out a suit for the junior prom.

He’d endured that only because Libby Remington was his date, and he’d wanted to impress her.

Tate rustled up a grin for his daughter, but his swift glance at Garrett was about as friendly as a splash of battery acid. “A castle with turrets and flags and a prospective moat,” he drawled. “Every kid in America ought to have one.”

“You think I overdid it?” Garrett teased. “Austin had a line on a retired circus elephant—rehab is boring him out of his ever-lovin’ mind, so he cruises the Internet on his laptop a lot—until I talked him out of it. Trust me, you could have done a lot worse than a castle, big brother.”

Right up until he rounded the last corner of the house before the kitchen patio and the acre of lawn abutting it, Tate hoped the thing would turn out to be no bigger than your average dollhouse.

No such luck. It dwarfed the equipment shed where he kept the field tractor, a couple of horse trailers, several riding lawn mowers and four spare pickup trucks. Set on rock slabs, the castle itself was made of some resin-type material, resembling chiseled stone, and stood so tall that it blotted out part of the sky.

Audrey, wearing a pointed princess hat with glittered-on stars and moons and a tinsel tassel trailing from it, waved happily from an upper window.

Tate turned to Garrett, one eyebrow raised. “What? No drawbridge?”

“That would have been a little over the top,” Garrett said modestly.

“Ya think?” Tate mocked.

Esperanza, beaming, flapped her apron, resembling a portly bird with only one wing as she inspected the monstrosity from all sides.

Tate waited until Princess Audrey had descended from the tower to fling herself at Garrett in a fit of gratitude—soon to be joined by Ava—before giving one wall a hard shove with the flat of his right hand.

The structure seemed sound, though he’d want to inspect every inch of it, inside and out, to make sure.

“Am I the only one who thinks this is ridiculous?” he asked. “An obscene display of conspicuous consumption?”

“The plastic is all recycled,” Garrett avowed, all but reaching around to pat himself on the back.

Tate rolled his eyes and walked away, leaving Garrett and Esperanza and the girls to admire McKettrick Court and returning to the trailer to unload poor old Bamboozle. He settled the pony in his stall, gave him hay and a little grain, and moved to the corral fence to look out over the land, where the horses and cattle grazed in their separate pastures.

At least there was one consolation, he thought; Austin hadn’t sent the elephant.

The sound of an arriving rig made him turn around, look toward the driveway. It was a truck, pulling a gleaming trailer behind it.

A headache thrummed between Tate’s temples. Maybe he’d been too quick to dismiss the pachyderm possibility.

Audrey and Ava, having heard the arrival, came bounding around the house, their shiny tassels trailing in the blue beginnings of twilight. Both of them were glitter-dappled from the pointed hats.

Tate and his daughters collided just as the driver was getting down out of the truck cab. A stocky older man, balding, the fella grinned and consulted his clipboard with a ceremonious flourish bordering on the theatrical.

“I’m looking for Miss Audrey and Miss Ava McKettrick,” he announced. Tate almost expected him to unfurl a scroll or blow a long brass horn with a velvet flag hanging from it.

Tate was already heading for the back of the trailer, his headache getting steadily worse.

Somehow, despite his bulk, the driver beat him there, blocked him bodily from opening the door and taking a look inside.

By God, Tate thought, if Austin had sent his kids an elephant…

“If you wouldn’t mind, Mr.—?” the driver said. His name, stitched on his khaki workshirt, was “George.”

“McKettrick,” Tate replied, through his teeth.

“The order specifically says I’m to deliver the contents of this trailer to the recipients and no one else.”

Tate swore under his breath, stepped back and, with a sweeping motion of one arm, invited George to do the honors.

“Who placed this order,” Tate asked, with exaggerated politeness, “if that information isn’t privileged or anything?”

George lowered a ramp, then climbed it to fling up the trailer’s rolling door.

No elephant appeared in the gap.

The suspense heightened—Audrey and Ava were huddled close to Tate on either side by then, fascinated—as George duly checked his clipboard.

“Says here, it was an A. McKettrick. Internet order. We don’t get many of those, given the nature of the—er—items.”

The twins were practically jumping up and down now, and Esperanza and Garrett had come up behind, hovering, to watch the latest drama unfold.

George disappeared into the shadowy depths, and a familiar clomping sound solved the mystery before two matching Palomino ponies materialized out of the darkness, shining like a pair of golden flames. Their manes and tails were cream-colored, brushed to a blinding shimmer, and each sported a bridle, a saddle and a bright pink bow the size of a basketball.

“Damn,” Garrett muttered, “the bastard one-upped me.”

“Yeah?” Tate replied, after pulling the girls back out of the way so George could unload the wonder horses. “Wait till you see what I got them.”

LIBBY HAD EATEN SUPPER—salad and soup—watched the evening news, checked her e-mail, brought the newspaper in from its plastic box by the front gate and done two loads of laundry when the telephone rang.

Damn, she hoped it wasn’t the manager at Poplar Bend, the town’s one and only condominium complex, calling to complain that Marva was playing her CDs at top volume again, and refused to turn down the music.

In the six months since their mother had suddenly turned up in Blue River in a chauffeur-driven limo and taken up residence in a prime unit at Poplar Bend, Libby and her two younger sisters, Julie and Paige, had gotten all sorts of negative feedback about Marva’s behavior.

None of them knew precisely what to do about Marva.

Picking up the receiver, she almost blurted out what she was thinking—“It’s not my week to watch her. Call Julie or Paige”—and by the time she had a proper “Hello” ready, Tate had already spoken.

No one else’s voice affected her in the visceral way his did.

“I need those dogs,” he said, almost furtively. “Tonight.”

Libby blinked. “I beg your pardon.”

“I need the dogs,” Tate repeated. Then, after a long pause that probably cost him, he added, “Please?”

“Tate, what on earth—? Do you realize what time it is?” She squinted at the kitchen clock, but the room was dark and since she’d just been passing through with a basket of towels from the dryer, she hadn’t bothered to flip on a light switch.

“Eight?” Tate said.

“Oh,” Libby said, mildly embarrassed. The hours since she’d left the Perk Up had dragged so that she thought surely it must be at least eleven.

“You know I’ll give them a good home,” Tate went on. “The dogs, I mean.”

Libby suppressed a sigh. The pups were curled up together on the hooked rug in the living room, sound asleep. Faced with the prospect of actually giving them up, she knew she was going to miss them—a lot.

“Yes,” she agreed. “I know. You can pick them up anytime tomorrow. Just stop by the shop and I’ll—”

“It has to be tonight, and—well—if you could deliver them—”

“Deliver them?”

“Look, it’s a lot to ask, I know that,” Tate said, “and I can’t explain right now, and I can’t leave, either, even though Garrett and Esperanza are both here, because it’s the girls’ birthday and everything.”

“And you want to give them the dogs for a present after all?”

“Something like that. Lib, I know it’s an imposition, but I’d really appreciate it if you could bring them out here right about now.”

“But you haven’t even seen them—”

“Dogs are dogs,” Tate said. “They’re all great. And I figure you wouldn’t have suggested I adopt them if they weren’t good around kids.”

“It’s normally not the best idea to give pets as gifts, Tate. Too much fuss and excitement isn’t good for the animal or the child.” What was she saying?

She’d been the one to suggest the adoption in the first place, and with good reason—the poor creatures needed the kind of home Tate could give them. With him, they would have the best of everything, and, more important, Tate was a dog person. He’d proved that with Crockett and a lot of other animals, too.

“We’re not talking about dyed chicks and rabbits at Easter here, Lib,” Tate replied. He was nearly whispering.

“What about kibble—and, well—things they’ll need?”

“They can survive on ground sirloin until I can get to the store and pick up dog chow tomorrow,” Tate reasoned. “I’m in a fix, Libby. I need your help.”

The pups had risen from the hooked rug and stood shoulder to shoulder in the doorway now, ears perked, tails wagging. Her heart sank a little at the sight.

“Okay,” Libby heard herself say. “We’ll be there as soon as I can load them into my car and make the drive.”

Tate let out a long breath. “Great,” he said. “I owe you, big-time.”

You can say that again, buster, Libby thought. How about fixing me up with a new heart, since you broke the one I’ve got?

The call ended.

“You’re going to be McKettrick dogs now,” Libby told the guys, with a sniffle in her voice. “Best of the best. You’ll probably have your own bedrooms and separate nannies.”

They wagged harder. It was impossible, of course, but Libby would have sworn they knew they were headed for a place where they could settle in and belong, for good.

“Heck,” she added, on a roll, “you’ll even get names.”

More wagging.

Libby found her purse and, after considerably more effort, her car keys. Since she lived across the alley from her café and walked everywhere but to the supermarket, she tended to misplace them.

If her aging, primer-splotched Impala would start, they were on their way.

“Want to come along for the ride?” she asked Hildie, resting on a rug of her own, in front of the couch.

Hildie yawned, stretched and went back to sleep.

“Guess that’s a ‘no,’” Libby said.

The pups were always ready to go when they heard the car keys jingle, and she almost tripped over them twice crossing the kitchen to the back door.

After loading the adoptees into the back seat of the rust-mobile, parked in her tilting one-car garage on the alley, she slid behind the wheel, closed her eyes to offer a silent prayer that the engine would start, stuck the key into the ignition and turned it.

The Impala’s motor caught with a huffy roar, the exhaust belching smoke.

Libby backed up slowly and drove with her headlights off until she’d passed Chief of Police Brent Brogan’s house at the end of the block. The chief had already warned her once about emissions standards—she was clearly in violation of said standards—and she’d made an appointment at the auto shop to get the problem fixed, twice. The trouble was, she’d had to cancel both times, once because Marva was acting up and neither Julie nor Paige was anywhere to be found, and once because a water pipe at the shop had burst and she’d been forced to call in a plumber, thereby blowing the budget.

All she needed now was a ticket.

She caught a glimpse of the chief through his living-room window as she pulled onto the street. His back was to her, and it looked as though he were playing cards or a board game with his children.

Still, Libby didn’t flip on her headlights until she reached the main street. Only when she’d passed the city limits did she give the Impala a shot of gas, and she kept glancing at the rearview mirror. Brent took his job seriously.

He was also one of Tate McKettrick’s best friends. If by some chance he’d seen her sneaking out of the alley in a cloud of illegal exhaust fumes, she would simply explain that she was delivering these two dogs to the Silver Spur because Tate wanted them tonight.

She bit her lower lip. Tate had said he owed her big-time. Well, then, he could just get her out of trouble with Brent, if she got into any.

But Libby made it all the way out to the Silver Spur without incident, and Tate must have been watching for her, because he was standing in the big circular driveway, with its hotel-size fountain, when she pulled in.

The dogs went wild in the back seat, scrabbling at the doors and rear windows, yipping to be set free.

Tate’s grin lit up the night.

He came to the car, opened the back door on the driver’s side and greeted the pair with ear-rufflings and the promise of sirloin for breakfast.

The dogs leaped to the paving stones and carried on like a pair of groupies finding themselves backstage at a rock concert.

Frankly, Libby had expected a little more pathos when it came time to part, since she’d been caring for these rascals for over two months, but evidently, the reluctance was all on her side.

“Hey, Lib,” Tate said, just when she’d figured he was planning to ignore her completely. “You saved my life. Want to come inside for some birthday cake?”

Lib. It wasn’t the first time he’d called her by the old nickname, even recently. He’d used it over the phone earlier, conning her into bringing the dogs out to his ranch that very night. Hearing it now, though, in person instead of over a wire, caused a deep emotional ache in her, a sort of yearning, as though she’d missed the last train or bus or airplane of a lifetime, and would now live out her days wandering forsaken in some wilderness.

“I shouldn’t,” Libby said.

Tate crouched to give the dogs the attention they continued to clamor for, but his face was turned upward, toward Libby, who was still sitting in her wreck of a car. Lights from the enormous portico over the front doors played in his hair. “Why not?” he asked.

“It’s late and Hildie’s home alone.”

“Hildie?”

“My dog,” she said.

“Is she sick?”

Libby shook her head.

“Old?”

Again, a shake.

That deadly grin of his—it should have been registered somewhere, like an assault weapon—crooked up the corner of his mouth. “Will she eat the curtains in your absence? Order pizza and smoke cigars? Log onto the Internet and cruise X-rated Web sites?”

Libby laughed. “No,” she said. Once, they’d been so close, she and Tate. She’d known his dog, Crockett, well enough to grieve almost as much over not seeing him anymore as she had over losing his master. It seemed odd, and somehow wrong, that Tate had never made Hildie’s acquaintance. “She’s a good dog. She’ll behave.”

“Then come in and have some birthday cake.”

Libby looked up at the front of that great house, and she remembered stolen afternoons in Tate’s bed, the summer after high school especially. Traveling further back in time, she recalled the night his parents came home early from a weekend trip and caught them swimming naked in the pool.

Mrs. McKettrick had calmly produced a bath sheet for Libby, bundled her into a pink terrycloth bathrobe, and driven her home with Libby, shivering, though the weather was hot and humid at the time.

Mr. McKettrick had ordered Tate to the study as she was leaving with Tate’s mom. “We’re going to have ourselves a talk, boy,” the rancher had said.

So much had changed since then.

Tate’s mom and dad were gone.

Her own father had long since died of cancer, after a lingering and painful decline.

Tate had married Cheryl, and they’d had twins together.

On the one hand, Libby really wanted to go inside and join the party.

On the other, she knew there would be too many other memories waiting to ambush her—mostly simple, ordinary ones, as it happened, like her and Tate doing their homework together, playing pool in the family room, watching movies and sharing bowls of popcorn. But it was the ordinary memories, she’d learned after losing her dad, that had the most power, the most poignancy.

With all her other problems, Libby figured she couldn’t handle so much poignancy just then.

“Not this time,” she said quietly, and shifted the Impala into Reverse.

“You need to get that exhaust fixed,” Tate told her. The smile was gone; his expression was serious. Moments before, she’d been convinced he’d only invited her inside to be polite, wanted to repay her in some small way for bringing the dogs to him on such short notice. Now she wondered if it actually mattered to him, that she accept his invitation. Was it possible that he was disappointed by her refusal?

She nodded. “It’s on the agenda. Good night, Tate.”

He looked down at the dogs, still frolicking around him as eagerly as if he’d stuffed raw T-bone steaks into each of his jeans pockets. “What are their names?”

“They don’t have any,” Libby said. “I call them ‘the dogs.’”

Tate chuckled. “That’s creative,” he replied. His body was half turned, as though the house and the people inside it were drawing him back, and she supposed they were. Garrett and Austin were both wild, in their different ways, but Tate had been born to be a family man, like his father. “You’re sure you won’t come in?”

“I’m sure.”

One of the big main doors opened, and the twins bounded out, dressed in identical pink cotton pajamas.

Libby’s heart lurched at the sight of them, and she put the Impala back in Park.

“Puppies!” they cried in unison, rushing forward.

Libby sat watching as the pups and the little girls immediately bonded, knowing all the while that she had to go.

“Happy birthday,” Tate told his daughters, with a tenderness Libby had never heard in his voice before. He glanced back at her, mouthed the word, “Thanks.”

Libby’s vision was blurred. She blinked rapidly and was about to suck it up, back out of that spectacular driveway and head on home, where she belonged, when suddenly one of the children, the one with glasses, ran to the side of her car and peered inside.

“Hi,” she said. “We have a castle. Would you like to see it?”

Libby looked up at the front of the house. “Not tonight, sweetheart, but thank you.”

“My name is Ava. You’re Libby Remington, aren’t you? You own the Perk Up Coffee Shop.”

Although Libby couldn’t recall actually meeting the girls, Blue River wasn’t a big place, and practically everybody knew everybody else. “Yes, I’m Libby. I hope you’re having a happy birthday.”

“We are,” the child said. “Uncle Garrett bought us our very own castle from Neiman-Marcus, and Uncle Austin sent us ponies. But Dad gave us what we really wanted—puppies!”

“Take these rascals inside and give them some water,” Tate told his daughters. He lingered, while the “rascals” followed the twins into the house without so much as a backward glance at Libby.

Libby’s throat tightened, partly because this was goodbye for her and the dogs, partly because of the little girls’ obvious joy and partly for reasons she could not have identified to save her life.

“I actually bought them a croquet set,” Tate confessed.

Libby frowned. In the old days, she and Julie and Paige had played a lot of backyard croquet with their dad, and she cherished the recollection. She’d been proud that when other daddies were on the golf course with their friends and business associates, hers had chosen to spend the time with her and her sisters. “What’s wrong with that?”

He sighed, stood with his arms folded, his head tilted back. He’d always loved looking at the stars, said that was why he’d never be happy in a big city. “Nothing,” he admitted. “But I kind of lost my head after the castle and the ponies were delivered. Call it male ego.”

“You’re not going to change your mind about the dogs, are you?” Libby asked, worried all over again.

Tate gripped the edge of her open window and bent to look in at her. His face was mere inches from hers, and for one terrible, wonderful, wildly confusing moment, she thought he was going to kiss her.

He didn’t, though.

“I’m not going to change my mind, Lib,” he said. “The mutts will have a home as long as I do.”

“You wouldn’t send them to town to live with your wife?”

“Ex-wife,” Tate said. “No, Cheryl’s not a dog person. Like the ponies, they’ll live right here on the Silver Spur for the duration.”

“Okay,” Libby said, now almost desperate to be gone.

And oddly, equally desperate to stay.

Tate straightened, smiled down at her. Half turned again, toward the house. Toward his daughters and the dogs that were already loved and would soon be named, toward his brother Garrett and Esperanza, the housekeeper.

But then he turned back.

“I don’t suppose you’d like to have dinner with me some night?” he asked, sounding as shy as he had that long-ago day when he’d asked her to the junior prom. “Soon?”