Читать книгу Big Sky River - Linda Lael Miller - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

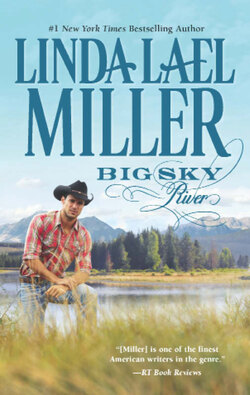

SHERIFF BOONE TAYLOR, enjoying a rare off-duty day, drew back his battered fishing rod and cast the fly-hook far out over the rushing, sun-spangled waters of Big Sky River. It ran the width of Parable County, Montana, that river, curving alongside the town of Parable itself like the crook of an elbow. Then it extended westward through the middle of the neighboring community of Three Trees and from there straight on to the Pacific.

He didn’t just love this wild, sprawling country, he reflected with quiet contentment. He was Montana, from the wide sky arching overhead to the rocky ground under the well-worn soles of his boots. That scenery was, to his mind, his soul made visible.

A nibble at the hook, far out in the river, followed by a fierce breaking-away, told Boone he’d snagged—and already lost—a good-sized fish. He smiled—he’d have released the catch anyway, since there were plenty of trout in his cracker-box-sized freezer—and reeled in his line to make sure the hook was still there. He found that it wasn’t, tied on a new one. For him, fishing was a form of meditation, a rare luxury in his busy life, a peaceful and quiet time that offered solace and soothed the many bruised and broken places inside him, while shoring up the strong ones.

He cast out his line again, and adjusted the brim of his baseball cap so it blocked some of the midmorning glare blazing in his eyes. He’d forgotten his sunglasses back at the house—if that junk heap of a double-wide trailer could be called a “house”—and he wasn’t inclined to backtrack to fetch them.

So he squinted, and toughed it out. For Boone, toughing things out was a way of life.

When his cell phone jangled in the pocket of his lightweight cotton shirt, worn unbuttoned over an old T-shirt, he muttered under his breath, grappling for the device. He’d have preferred to ignore it and stay inaccessible for a little while longer. As sheriff, though, he didn’t have that option. He was basically on call, 24/7, like it or not.

He checked the number, recognized it as Molly’s, and frowned slightly as he pressed the answer bar. She and her husband, Bob, had been raising Boone’s two young sons, Griffin and Fletcher, since the dark days following the death of their mother and Boone’s wife, Corrie, a few years before. A call from his only sibling was usually benign—Molly kept him up-to-date on how the boys were doing—but there was always the possibility that the news was bad, that something had happened to one or both of them. Boone had reason to be paranoid, after all he’d been through, and when it came to his kids, he definitely was.

“Molly?” he barked into the receiver. “What’s up?”

“Hello, Boone,” Molly replied, and sure enough, there was a dampness to her response, as though she’d been crying, or was about to, anyhow. And she sounded bone weary, too. She sniffled and put him out of his misery, at least temporarily. “The boys are both fine,” she said. “It’s about Bob. He broke his right knee this morning—on the golf course, of all places—and the docs in Emergency say he’ll need surgery right away. Maybe even a total replacement.”

“Are you crying?” Boone asked, his tone verging on a challenge as he processed the flow of information she’d just let loose. He hated it when women cried, especially ones he happened to love, and couldn’t help out in any real way.

“Yes,” Molly answered, rallying a little. “I am. After the surgery comes rehab, and then more recovery—weeks and weeks of it.”

Boone didn’t even reel in his line; he just dropped the pole on the rocky bank of the river and watched with a certain detached interest as it began to bounce around, an indication that he’d gotten another bite. “Molly, I’m sorry,” he murmured.

Bob was the love of Molly’s life, the father of their three children, and a backup dad to Griff and Fletch, as well. Things were going to be rough for him and for the rest of the family, and there wasn’t a damn thing Boone could do to make it better.

“Talk to me, Molly,” he urged gruffly, when she didn’t reply right away. He could envision her, struggling to put on a brave front, as clearly as if they’d been standing in the same room.

The pole was being pulled into the river by then; he stepped on it to keep it from going in and fumbled to cut the line with his pocketknife while Molly was still regathering her composure, keeping the phone pinned between his shoulder and his ear so his hands stayed free. Except for the boys and her and Bob’s kids, Molly was all the blood kin Boone had left, and he owed her everything.

“It’s—” Molly paused, drew a shaky breath “—it’s just that the kids have summer jobs, and I’m going to have my hands full taking care of Bob....”

Belatedly, the implications sank in. Molly couldn’t be expected to look after her husband and Griffin and Fletcher, too. She was telling her thickheaded brother, as gently as she could, that he had to step up now, and raise his own kids. The prospect filled him with a tangled combination of exuberance and pure terror.

Boone pulled himself together, silently acknowledged that the situation could have been a lot worse. Bob’s injury was bad, no getting around it, but he could be fixed. He wasn’t seriously ill, the way Corrie had been.

Visions of his late wife, wasted and fragile after a long and doomed battle with breast cancer, unfurled in his mind like scenes from a very sad movie.

“Okay,” he managed to say. “I’ll be there as soon as I can. Are you at home, or at the hospital?”

“Hospital,” Molly answered, almost in a whisper. “I’ll probably be back at the house before you get here, though.”

Boone nodded in response, then spoke. “Hang on, sis,” he said. “I’m as good as on my way.”

“Griffin and Fletcher don’t know yet,” she told him quickly. “About what’s happened to Bob, I mean, or that you’ll be coming to take them back to Parable with you. They’re with the neighbor, Mrs. Mills. I want to be there when they find out, Boone.”

Translation: If you get to the boys before I do, don’t say anything about what’s going on. You’ll probably bungle it.

“Good idea,” Boone conceded, smiling a little. Molly was still the same bossy big sister she’d always been—thank God.

Molly sucked in another breath, sounded calmer when she went on, though she had to be truly shaken up. “I know this is all pretty sudden—”

“I’ll deal with it,” Boone said, picking up the fishing pole, reeling in the severed line and starting toward his truck, a rusted-out beater parked up the bank a ways, alongside a dirt road. He knew he ought to replace the rig, but most of the time he drove a squad car, and, besides, he hated the idea of going into debt.

“See you soon,” Molly said, and Boone knew even without seeing her that she was tearing up again.

Boone was breathless from the steep climb by the time he reached the road and his truck, even though he was in good physical shape. His palm sweated where he gripped the cell phone, and he tossed the fishing pole into the back of the pickup with the other hand. It clattered against the corrugated metal. “Soon,” he confirmed.

They said their goodbyes, and the call ended.

By then, reality was connecting the dots to form an image in his brain, one of spending a whole summer, if not longer, with two little boys who basically regarded him as an acquaintance rather than a father. And it was a natural reaction on their part; he’d essentially abdicated his parental role after Corrie had died, packing off the kids—small and baffled—to Missoula to stay with Molly and Bob and their older cousins. In the beginning, Boone had meant for the arrangement to be temporary—all of them had—but one thing led to another, and pretty soon, the distance between him and the children became emotional as well as physical. While his closest friends had been needling him to man up and bring Griffin and Fletcher home practically since the day after Corrie’s funeral, and he missed those boys with an ache that resembled the insistent, pulsing throb of a bad tooth, he’d always told himself he needed just a little more time. Just until after the election, and then until he’d gotten into the swing of a new job, since being sheriff was a lot more demanding than being a deputy, like before, then until he could replace the double-wide with a decent house.

Until, until, until.

Now, it was put up or shut up. Molly would need all her personal resources, physical, spiritual and emotional, to steer Bob and her own children through the weeks ahead.

He sat there in the truck for a few moments, with the engine running and the phone still in his hand, picturing the long and winding highway between Parable and Missoula, and finally speed-dialed his best friend, Hutch Carmody.

“Yo, Sheriff Taylor,” Hutch greeted him cheerfully. “What can I do you out of?”

Married to his longtime love, the former Kendra Shepherd, with a five-year-old stepdaughter, Madison, and a new baby due to join the outfit in a month or so, Hutch seemed to be in a nonstop good mood these days.

It was probably the regular sex, Boone figured, too distracted to be envious but still subliminally aware that he’d been living like a monk since Corrie had died. “I need to borrow a rig,” he said straight out. “I’ve got to get to Missoula quick, and this old pile of scrap metal might not make it there and back.”

Hutch got serious, right here, right now. “Sure,” he said. “What’s going on? Are the kids okay?”

Though they’d only visited Parable a few times since they’d gone to live with Molly and Bob, Griffin and Fletcher looked up to Hutch, probably wished he was their dad, instead of Boone. “The boys are fine,” Boone answered. “But Molly just called, and she says Bob blew a knee on the golf course and he’s about to have surgery. Obviously, she’s got all she can do to look after her own crew right now, so I’m on my way up there to bring the kids home with me.”

Hutch swore in a mild exclamation of sympathy for the world of hurt he figured Bob was in, and then said, “I’m sorry to hear that—about Bob, I mean. Want me to come along, ride shotgun and maybe provide a little moral support?”

“I appreciate the offer, Hutch,” Boone replied, sincerely grateful for the man’s no-nonsense, unshakable friendship. “But I think I need some alone-time with the kids, so I can try to explain what’s happening on the drive back from Missoula.”

Griffin was seven years old and Fletcher was only five. Boone could “explain” until he was blue in the face, but they weren’t going to understand why they were suddenly being jerked out of the only home and the only family they really knew. Griffin, being a little older, remembered his mother vaguely, remembered when the four of them had been a unit. The younger boy, Fletcher, had no memories of Corrie, though, and certainly didn’t regard Boone as his dad. It was Bob who’d raised him and his brother, taken them to T-ball games, to the dentist, to Sunday school.

“Not a problem,” Hutch agreed readily. “The truck is gassed up and ready to roll. Do you want me to drop it off at your place? One of the hands could follow me over in another rig and—”

“I’ll stop by the ranch and pick it up instead,” Boone broke in, not wanting to put his friend to any more trouble than he already had. “See you in about fifteen minutes.”

“Okay,” Hutch responded, sighing the word, and the call was over.

Boone stayed a hair under the speed limit, though just barely, the whole way to the Carmody ranch, called Whisper Creek, where he found Hutch waiting beside the fancy extended-cab truck he’d purchased the year before, when he and Kendra were falling in love for the second time. Or maybe just realizing that they’d never actually fallen out of it in the first place.

Now, Hutch was hatless, with his head tilted a little to one side the way he did when he was pondering some enigma, and his hands were wedged backward into the hip pockets of his worn jeans. Kendra, a breathtakingly beautiful blonde, stood beside him, pregnant into the next county.

“Have you had anything to eat?” Kendra called to Boone, the instant he’d stopped his pickup. Dust roiled around her from under the truck’s wheels, but she was a rancher’s wife now, and unfazed by the small stuff.

Boone got out of the truck and walked toward them. He kissed Kendra’s cheek and tried to smile, though he couldn’t quite bring it off. “What is it with women and food?” he asked. “A man could be lying flat as a squashed penny on the railroad track, and some female would come along first thing, wanting to feed him something.”

Hutch chuckled at that, but the quiet concern in his gaze made Boone’s throat pull tight like the top of an old-time tobacco sack. “It’s a long stretch to Missoula,” Hutch observed, quietly affable. “You might get hungry along the way.”

“I’ll make sandwiches,” Kendra said, and turned to duck-waddle toward the ranch house. Compared with Boone’s double-wide, the place looked like a palace, with its clapboard siding and shining windows, and for the first time in his life, Boone wished he had a fine house like that to bring his children home to.

“Don’t—” Boone protested, but it was too late. Kendra was already opening the screen door, stepping into the kitchen beyond.

“Let her build you a lunch, Boone,” Hutch urged, his voice as quiet as his manner. Since the wedding, he’d been downright Zen-like. “She’ll be quick about it, and she wants to help whatever way she can. We all do.”

Boone nodded, cleared his throat, looked away. Hutch’s dog, a black mutt named Leviticus, trotted over to nose Boone’s hand, his way of saying howdy. Kendra’s golden retriever, Daisy, was there, too, watchful and wagging her tail.

Boone ruffled both dogs’ ears, straightened, looked Hutch in the eye again. Neither of them spoke, but it didn’t matter, because they’d been friends for so long that words weren’t always necessary.

Boone was worried about bringing the boys back to his place for anything longer than a holiday weekend, and Hutch knew that. He clearly cared and sympathized, but at the same time, he was pleased. There was no need to give voice to the obvious.

Kendra returned almost right away, moving pretty quickly for somebody who could be accused of smuggling pumpkins. She carried a bulging brown paper bag in one hand, holding it out to Boone when she got close enough. “Turkey on rye,” she said. “With pickles. I threw in a couple of hard-boiled eggs and an apple, too.”

He took the bag, muttered his thanks, climbed into Hutch’s truck and reached through the open window to hand over the keys to the rust-bucket he’d driven up in. Some swap that was, he thought ruefully. His old buddy was definitely getting the shitty end of this stick.

“Give Molly and Bob our best!” Kendra called after him, as Boone started up the engine and shifted into Reverse. “If there’s anything we can do—”

Boone cut her off with a nod, raised a hand in farewell and drove away.

After a brief stop in Parable, to get some cash from an ATM, he’d keep the pedal to the metal all the way to Missoula. Once there, he and Molly would explain things, together.

God only knew how his sons would take the news—they were always tentative and quiet on visits to Parable, like exiles to a strange new planet, and visibly relieved when it was time to go back to the city.

One thing at a time, Boone reminded himself.

* * *

TARA KENDALL STOOD in front of her chicken coop, surrounded by dozens of cackling hens, and second-guessed her decision to leave a high-paying, megaglamorous job in New York and reinvent herself, Green Acres–style, for roughly the three thousandth time since she’d set foot in Parable, Montana, a couple years before.

She missed her small circle of friends back East, and her twelve-year-old twin stepdaughters, Elle and Erin. She also missed things, like sidewalk cafés and quirky shops, Yellow Cab taxis and shady benches in Central Park, along with elements that were harder to define, like the special energy of the place, the pure purpose flowing through the crowded streets like some unseen river.

She did not, however, miss the stress of trying to keep her career going in the midst of a major economic downturn, with her ex-husband, Dr. James Lennox, constantly complaining that she’d stolen his daughters’ love from him when they divorced, along with a chunk of his investments and real estate assets.

Tara didn’t regret the settlement terms for a moment—she’d forked over plenty of her own money during their rocky marriage, helping to get James’s private practice off the ground after he left the staff of a major clinic to go out on his own—and as for the twins’ affection, she’d gotten that by being there for Elle and Erin, as their father so often hadn’t, not by scheming against James or undermining him to his children.

Even if Tara had wanted to do something as reprehensible as coming between James and the twins, there wouldn’t have been any need, because the girls were formidably bright. They’d figured out things for themselves—their father’s serial affairs included. Since he’d never seemed to have time for them, they’d naturally been resentful when they found out, quite by accident, that their dad had bent his busy schedule numerous times to take various girlfriends on romantic weekend getaways.

Tara’s golden retriever, Lucy, napping on the shady porch that ran the full length of Tara’s farmhouse, raised her head, ears perked. In the next instant, the cordless receiver for the inside phone rang on the wicker table set between two colorfully cushioned rocking chairs.

Hurrying up the front steps, Tara grabbed the phone and said, “Hello?”

“Do you ever answer your cell?” her former husband demanded tersely.

“It’s charging,” Tara said calmly. James loved to argue—maybe he should have become a lawyer instead of a doctor—and Tara loved to deprive him of the satisfaction of getting a rise out of her. Then, as another possibility dawned on her, she suppressed a gasp. “Elle and Erin are all right, aren’t they?”

James remained irritable. “Oh, they’re fine,” he said scathingly. “They’ve just chased off the fourth nanny in three weeks, and the agency refuses to send anyone else.”

Tara bit back a smile, thinking of the mischievous pair. They were pranksters, and they got into plenty of trouble, but they were good kids, too, tenderhearted and generous. “At twelve, they’re probably getting too old for nannies,” she ventured. James never called to chat, hadn’t done that even when they were married, standing in the same room or lying in the same bed. No, Dr. Lennox always had an agenda, and she was getting a flicker of what it might be this time.

“Surely you’re not suggesting that I let them run wild, all day every day, for the whole summer, while I’m in the office, or in surgery?” James’s voice still had an edge to it, but there was an undercurrent of something else—desperation, maybe. Possibly even panic.

“Of course not,” Tara replied, plunking down in one of the porch rocking chairs, Lucy curling up at her feet. “Day camp might be an option, if you want to keep them busy, or you could hire a companion—”

“Day camp would mean delivering my daughters somewhere every morning and picking them up again every afternoon, and I don’t have time for that, Tara.” There it was again, the note of patient sarcasm, the tone that seemed to imply that her IQ was somewhere in the single digits and sure to plunge even lower. “I’m a busy man.”

Too busy to care for your own children, Tara thought but, of course, didn’t say. “What do you want?” she asked instead.

He huffed out a breath, evidently offended by her blunt question. “If that attitude isn’t typical of you, I don’t know what is—”

“James,” Tara broke in. “You want something. You wouldn’t call if you didn’t. Cut to the chase and tell me what that something is, please.”

He sighed in a long-suffering way. Poor, misunderstood James. Always so put-upon, a victim of his own nobility. “I’ve met someone,” he said.

Now there’s a news flash, Tara thought. James was always meeting someone—a female someone, of course. And he was sure that each new mistress was The One, his destiny, harbinger of a love that had been written in the stars instants after the Big Bang.

“Her name is Bethany,” he went on, sounding uncharacteristically meek all of a sudden. James was a gifted surgeon with a high success rate; modesty was not in his nature. “She’s special.”

Tara refrained from comment. She and James were divorced, and she quite frankly didn’t care whom he dated, “special” or not. She did care very much, however, about Elle and Erin, and the fact that they always came last with James, after the career and the golf tournaments and the girlfriend du jour. Their own mother, James’s first wife, Susan, had contracted a bacterial infection when they were just toddlers, and died suddenly. It was Tara who had rocked the little girls to sleep, told them stories, bandaged their skinned elbows and knees—to the twins, she was Mom, even in her current absentee status.

“Are you still there?” James asked, and the edge was back in his voice. He even ventured a note of condescension.

“I’m here,” Tara said, after swallowing hard, and waited. Lucy sat up, rested her muzzle on Tara’s blue-jeaned thigh, and watched her mistress’s face for cues.

“The girls are doing everything they can to run Bethany off,” James said, after a few beats of anxious silence. “We need some—some space, Bethany and I, I mean—just the two of us, without—”

“Without your children getting underfoot,” Tara finished for him after a long pause descended, leaving his sentence unfinished, but she kept her tone moderate. By then she knew for sure why James had called, and she already wanted to blurt out a yes, not to please him, but because she’d missed Elle and Erin so badly for so long. Losing daily contact with them had been like a rupture of the soul.

James let the remark pass, which was as unlike him as asking for help or giving some hapless intern, or wife, the benefit of a doubt. “I was thinking—well—that you might enjoy a visit from the twins. School’s out until fall, and a few weeks in the country—maybe even a month or two—would probably be good for them.”

Tara sat up very straight, all but holding her breath. She had no parental rights whatsoever where James’s children were concerned; he’d reminded her of that often enough.

“A visit?” she dared. The notion filled her with two giant and diametrically opposed emotions—on the one hand, she was fairly bursting with joy. On the other, she couldn’t help thinking of the desolation she’d feel when Elle and Erin returned to their father, as they inevitably would. Coping with the loss, for the second time, would be difficult and painful.

“Yes.” James stopped, cleared his throat. “You’ll do it? You’ll let the twins come out there for a while?”

“I’d like that,” Tara said carefully. She was afraid to show too much enthusiasm, even now, when she knew she had the upper hand, because showing her love for the kids was dangerous with James. He was jealous of their devotion to her, and he’d always enjoyed bursting her bubbles, even when they were newlyweds and ostensibly still happy. “When would they arrive?”

“I was thinking I could put them on a plane tomorrow,” James admitted. He was back in the role of supplicant, and Tara could tell he hated it. All the more reason to be cautious—there would be a backlash, in five minutes or five years. “Would that work for you?”

Tara’s heartbeat picked up speed, and she laid the splayed fingers of her free hand to her chest, gripping the phone very tightly in the other. “Tomorrow?”

“Is that too soon?” James sounded vaguely disapproving. Of course he’d made himself the hero of the piece, at least in his own mind. The self-sacrificing father thinking only of his daughters’ highest good.

What a load of bull.

Not that she could afford to point that out.

“No,” Tara said, perhaps too quickly. “No, tomorrow would be fine. Elle and Erin can fly into Missoula, and I’ll be there waiting to pick them up.”

“Excellent,” James said, with obvious relief. Not “thank you.” Not “I knew I could count on you.” Just “Excellent,” brisk praise for doing the right thing—which was always whatever he wanted at the moment.

That was when Elle and Erin erupted into loud cheers in the background, and the sound made Tara’s eyes burn and brought a lump of happy anticipation to her throat. “Text me the details,” she said to James, trying not to sound too pleased, still not completely certain the whole thing wasn’t a setup of some kind, calculated to raise her hopes and then dash them to bits.

“I will,” James promised, trying in vain to shush the girls, who were now whooping like a war party dancing around a campfire and gathering momentum. “And, Tara? Thanks.”

Thanks.

There it was. Would wonders never cease?

Tara couldn’t remember the last time James had thanked her for anything. Even while they were still married, still in love, before things had gone permanently sour between them, he’d been more inclined to criticize than appreciate her.

Back then, it seemed she was always five pounds too heavy, or her hair was too long, or too short, or she was too ambitious, or too lazy.

Tara put the brakes on that train of thought, since it led nowhere. “You’re welcome,” she said, carefully cool.

“Well, then,” James said, clearly at a loss now that he’d gotten his way, fresh out of chitchat. “I’ll text the information to your cell as soon as I’ve booked the flights.”

“Great,” Tara said. She was about to ask to speak to the girls when James abruptly disconnected.

The call was over.

Of course Tara could have dialed the penthouse number, and chatted with Elle and Erin, who probably would have pounced on the phone, but she’d be seeing them in person the next day, and the three of them would have plenty of time to catch up.

Besides, she had things to do—starting with a shower and a change of clothes, so she could head into town to stock up on the kinds of things kids ate, like cold cereal and milk, along with those they tended to resist, like fresh vegetables.

She needed to get the spare room aired out, put sheets on the unmade twin beds, outfit the guest bathroom with soap and shampoo, toothbrushes and paste, in case they forgot to pack those things, tissues and extra toilet paper.

Lucy followed her into the house, wagging her plumy tail. Something was up, and like any self-respecting dog, she was game for whatever might happen next.

The inside of the farmhouse was cool, because there were fans blowing and most of the blinds were drawn against the brightest part of the day. The effect had been faintly gloomy, before James’s call.

How quickly things could change, though.

After tomorrow, Tara was thinking, she and Lucy wouldn’t be alone in the spacious old house—the twins would fill the place with noise and laughter and music, along with duffel bags and backpacks and vivid descriptions of the horrors wrought by the last few nannies in a long line of post-divorce babysitters, housekeepers and even a butler or two.

She smiled as she and Lucy bounded up the creaky staircase to the second floor, along the hallway to her bedroom. Most of the house was still under renovation, but this room was finished, having been a priority. White lace curtains graced the tall windows, and the huge “garden” tub was set into the gleaming plank floor, directly across from the fireplace.

The closet had been a small bedroom when Tara had purchased the farm, but she’d had it transformed into every woman’s dream storage area soon after moving in, to contain her big-city wardrobe and vast collection of shoes. It was silly, really, keeping all these supersophisticated clothes when the social scene in Parable called for little more than jeans and sweaters in winter and jeans and tank tops the rest of the time, but, like her books and vintage record albums, Tara hadn’t been able to give them up.

Parting with Elle and Erin had been sacrifice enough to last a lifetime—she’d forced herself to leave them, and New York, in the hope that they’d be able to move on, and for the sake of her own sanity. Now, they were coming to Parable, to stay with her, and she was filled with frightened joy.

She selected a red print sundress and white sandals from the closet and passed up the tub for the room just beyond, where the shower stall and the other fixtures were housed.

Lucy padded after her in a casual, just-us-girls way, and sat down on a fluffy rug to wait out this most curious of human endeavors, a shower, her yellow-gold head tilted to one side in an attitude of patient amazement.

Minutes later, Tara was out of the shower, toweling herself dry and putting on her clothes. She gave her long brown hair a quick brushing, caught it up at the back of her head with a plastic squeeze clip and jammed her feet into the sandals. Her makeup consisted of a swipe of lip gloss and a light coat of mascara.

Lucy trailed after her as she crossed the wider expanse of her bedroom and paused at one particular window, for reasons she couldn’t have explained, to look over at Boone Taylor’s place just across the field and a narrow finger of Big Sky River.

She sighed, shook her head. The view would have been perfect if it wasn’t for that ugly old trailer of Boone’s, and the overgrown yard surrounding it. At least the toilet-turned-planter and other examples of extreme bad taste were gone, removed the summer before with some help from Hutch Carmody and several of his ranch hands, but that had been the extent of the sheriff’s home improvement campaign, it seemed.

She turned away, refusing to succumb to irritation. The girls were as good as on their way. Soon, she’d be able to see them, hug them, laugh with them.

“Come on, Lucy,” she said. “Let’s head for town.”

Downstairs, she took her cell phone off the charger, and she and the dog stepped out onto the back porch, walked toward the detached garage where she kept her sporty red Mercedes, purchased, like the farm itself, on a whimsical and reckless what-the-hell burst of impulse, and hoisted up the door manually.

Fresh doubt assailed her as she squinted at the car.

It was a two-seater, after all, completely unsuitable for hauling herself, two children and a golden retriever from place to place.

“Yikes,” she said, as something of an afterthought, frowning a little as she opened the passenger-side door of the low-slung vehicle so Lucy could jump in. Before she rounded the front end and slid behind the steering wheel, Tara was thumbing the keypad in a familiar sequence.

Her friend answered with a melodic, “Hello.”

“Joslyn?” Tara said. “I think I need to borrow a car.”