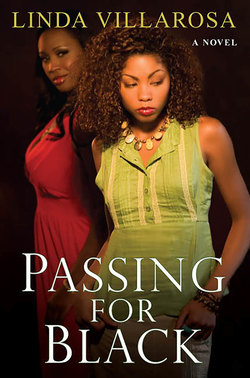

Читать книгу Passing For black - Linda Villarosa - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеThe next afternoon, I wound my way through the brightly lit tables, keeping my head down to avoid eye contact with any of the other magazine editors, flitting like sparrows through the Brice-Castle Publishing cafeteria. I found a table and put down my tray, looking impatiently for Mae to join me. I hated sitting alone, and I was beyond starving. I pulled a tube of lipstick in a shade called Dubonnet from my jacket pocket and applied it as best I could without looking. I didn’t really want Mae to give me a hard time about “fixing up.”

Appraising myself realistically, I had some nice features—smooth, even skin; brown, slightly slanted eyes; straight, white teeth thanks to braces and a retainer; thick, curly hair. My legs were long and, I thought, cute, and I had a pretty good-looking butt. The package was almost beautiful, though I lacked the bearings, style or attitude of a beautiful person. Despite the intense pressure to look good, beaten into anyone who worked at a fashion magazine and had the guts to sashay through this cafeteria, I never quite pulled it together. I didn’t understand makeup, so I avoided all but lipstick. My clothes, despite Mae’s constant coaching and cajoling, were never hooked up correctly. I was always a couple of seasons behind. I generally thought people who were fashion forward were simply strange, until I found myself—and the rest of the planet—wearing their previously avant garde pieces a year later. My hair was a disorganized tangle of thick curls, springy and random.

Mae had paused for a moment, buttonholed by a woman whose black dress hung off her, like a garment slipping from a hanger. She and Mae were actually wearing the same Calvin Klein dresses, size 2 and 16, respectively. Mae’s dress was orange since she had given up wearing black, because it was now “tired.” The hanger stood on her tiptoes and whispered something conspiratorially into Mae’s ear. “I heard that,” she said, clapping the hanger on the back heartily, nearly knocking the dress off her thin shoulders, before moving on.

Mae was my best friend, my only real friend, at work. She was an associate features writer at Vicarious, a celebrity fashion magazine. I was an associate editor at Désire, another publication in the Brice-Castle stable. We had started at the company the same week and had been seated next to each other at Brice-Castle’s mandatory new employees’ welcome lunch.

“Oh no, they put me at the black table,” she had said loudly as she sat down next to me.

“Welcome, my sistah,” I had replied, smiling at her and ignoring the uncomfortable looks of the other three women and the man seated with us.

Mae had thrown back her head and answered with a raucous, full-on laugh. Right away, her gummy, gap-toothed smile and crinkly eyes felt like home.

Everyone liked Mae. She had created a kind of universal “you-go-girl” black woman persona. She was a magnet to the wispy women and gay men who peopled our company: they were drawn by the confidence and good cheer that clung lightly to her like a misting of cologne. Many felt close to her, though she managed to keep the more textured aspects of her persona secreted away, like an intricately folded dollar stuffed into her brassiere.

Mae had grown up in Iuka, Mississippi, and no amount of New York sophistication could drive out her Southern roots. She was definitely country fried Prada. Two weeks after we’d met, on our way to getting bent on vodka martinis neither of us could afford at the Oak Room in the Plaza Hotel, Mae had revealed to me that just before her fifth birthday, she had announced to her mother that once she was eighteen, she was “outta Dodge.” She vowed to someday live in New York City in an apartment high in the sky, all by herself.

“The first time I said it, Mama wiped her hands on her apron and said ‘uh-huh,’” Mae had confided in me, dragging out the uhs and huhs for five full seconds. “By the second time I said it, she told me to ‘stop the foolishness.’ But when I was still saying it two years later, she said that ‘if you see yourself there, you’re as good as there.’”

The day she graduated from Barnard, her family was there. Ten of them had piled out of an Amtrak sleeper car, greasy shoe boxes of fried chicken and deviled eggs in tow. They spread themselves out on the Lehman Lawn, screaming and holding up signs and banging on noisemakers when Mae walked up to get her diploma. Ignoring the chilly stares of her classmates and their parents, she waved and flashed her gummy smile and shouted “I love y’all,” as she tottered past the podium on itty bitty high-heeled shoes.

“They were so fucking country, but I loved having them there.” Her eyes had gotten round and watery as she told the story, and mine did, too.

After several years in publishing, Mae had finally grown tired of trying to explain her accent, tone down her loud laugh, and justify how some ’Bama had crashed her way into the ranks of Manhattan publishing. Rather than reinvent herself—again—she began to simply withhold parts of herself. Several years ago, she had limited her vocabulary around our co-workers to three phrases: “I heard that,” “I know you’re right,” and “I’m scared of you.” People found her wise and a little mysterious.

“Hey you,” she said, her tray clattering onto the table. The four plates of overpriced haute cuisine must’ve cost her close to thirty dollars. I loved to eat but hated to pay, so the small, expensive portions the cafeteria served were a source of irritation. I secretly believed that the editors at the company’s magazines suffered from disordered eating, so bigger portions made them nervous. They actually preferred to pay more for smaller portions. The few who weren’t anorexic were bulimic, ordering double portions, then sneaking off to a bathroom on another floor—oh God, not their own—to throw up in the afternoon. Until last year, they had favored the fifth floor, inhabited by the company’s accounting department. After several numbers crunchers complained about the smell, HR issued a clumsily worded memo and the problem ceased.

“I got you the salmon Nicoise with extra potatoes and the balsamic chicken and mango stir-fry,” Mae said. She reached into her orange and yellow Pucci tote and pulled out a large bubble-wrapped package. Carefully, she uncovered two pieces of china, delicately painted with green leaves; two sets of silverware; two checkered green napkins and two cocktail glasses splashed with white magnolias, Mississippi’s state flower. She insisted that the “insulting plastic mess” would ruin our meals. I had long ago decided not to be embarrassed by this over-the-top display of decorum.

“Hey, what’s up with you, today, you okay?” She moved two tidy servings onto our plates and poured bottled iced tea into the glasses. She added an extra packet of sugar to each.

“Yeah, I’m cool,” I said, piercing the chicken with my fork, and popping a large, juicy piece into my mouth. It was oddly tasteless.

“Oh no—not again,” she said, ignoring me as she chewed a mouthful of tortellini. “Have you set the date?”

“Not yet.” I shifted my eyes away from hers.

“Angela, I love you, but, okay, stop it!” Mae said, nearly shouting. Two hangers stopped pushing their food around their plates and looked up at us.

“Please…” I didn’t want to get into this with her. There was so much she didn’t know.

“No, PLEASE! Keith is a good man. He’s awright-looking for an academic, and he loves you and wants to marry you,” she said, ticking off Keith’s strong points on her left hand. “The boy’s romantic, you’ve got to give him that. Remember your engagement?”

After four years together, I had mentioned to Keith offhandedly that I longed to go to Africa. “By the time I see the motherland, I’ll be a grandmother,” I had said as we climbed into bed one night. A month later, he surprised me with a ten-day trip to South Africa. After visiting Johannesburg, Cape Town and a lavish game lodge in Kruger National Park, we ended up in Franschhoek, South Africa’s lush wine country. Over dinner on a terrace with a view of Table Mountain, Keith said to me, “Angela, ‘you make my life fine, fine as wine.’” Then he smiled. Langston, his favorite poet. “Will you marry me?”

Looking way beyond corny down on one knee, he presented me with a 4-carat diamond ring, an heirloom passed down from his grandmother, Lottie. It looked as big as a suitcase on my finger. Between the ring and the poem, and the motherland and the ice-cold Sauvignon blanc, I started sobbing uncontrollably.

Crying, too, Keith had stroked my hand. “Uh, ‘baby, I’m never gonna give you up, so don’t make me wait too long,’” he said, deepening his voice. Barry White, his other favorite poet. Even more cornball. Through the tears and giggles and second thoughts, I managed to sputter out a “yes.”

“Besides that fantastic proposal, get real,” Mae said, reaching over and stabbing a bite of salmon from my plate. “He’s a man, he’s black, and he’s got hair and vital signs.”

“Okay, okay.” I pushed a piece of salmon and an olive onto my fork.

“There is a SHORTAGE, I know you know that—catch up.” She snapped the fingers of her left hand, pushing a stray piece of asparagus onto her fork with her pinkie.

“Oh, knock it off,” I said, grabbing her hand to stop the irritating snapping. “I’m not rushing into marriage because of your crackpot scare tactics.”

“RUSH, you’ve been with this man, what, six years? Plus, you do love him.” This was not a question.

“Yes, I do love him,” I said, raising my voice, too. “But, Mae, how do I know that Keith is my soul mate?”

“Shut up—PA-lease. No one marries their soul mate, except for lesbians, and they can’t get married.” She widened her eyes and stared at me. I felt my heart jump, lurching out of sync for a beat as Caitlin Getty’s face flashed in my mind.

“Break up with him, then,” Mae continued, taking her napkin from her lap and dabbing at a bit of stray sauce from the corner of her mouth. “Then see how easy it is to find your so-called soul mate. Forget the stats; look around at black women who are thirty, your age shortly. Where are a bunch of eligible black men jumping in line to date us?” she said.

“I just read an article in one of the black magazines that said sisters have our expectations too high and that we need to date bus drivers, rather than wait for a man on our level. You know what, that tired advice doesn’t even work anymore. I was eating up at Amy Ruth’s last week, and I heard two women fighting over a guy—who was in prison. Now, you do the math: If there are two women fighting over every guy in lockdown, that means four are fighting over every bus driver and eight are fighting over every college professor, and God knows how many are fighting over an investment banker.”

“And your point is?” I asked, wishing she’d pipe down.

“You know what—I turned the page in that magazine,” she continued, waving her fork. “And I was advised to draw a hot bath, light a candle and marry myself. Why would a magazine tell you to marry yourself if there was a living, breathing person to actually marry?” She was getting very worked up.

“I get it,” I said. I wanted to get her off this subject.

“No, you don’t,” Mae said as she stuck her fork into a neat mound of risotto. “Miss Wright, where are you going to look for Mr. Right? Here? You work at a friggin’ women’s magazine company. Do you see any men here?; well, any that won’t be on the 3:50 train to the Pines ferry on Fridays?”

“Okay, if things are soooo dire, why are you always so picky?” I looked at her pointedly, raising my eyebrows.

“Girl, please, I am not picky, I’m discriminating.”

“Girl, please yourself.” I was irritated, talking much more black than usual. My “black woman voice” seemed to have more authority.

“Listen, Mae, maybe I’m scared, okay?” I said, feeling tired and shaky. I reached across the table and gripped her hand. I wished I could tell Mae about my secret desires for women. But I was afraid. I didn’t know if I’d ever be able to tell her. Maybe after I was safely married to Keith. Or maybe this wasn’t the kind of thing I would ever tell my best friend. These were thoughts that I would always savor and later punish myself for.

“Mae, I’ll be okay. I just need more time.”

“I know, I know, of course you are, of course you do,” She moved her hand from underneath and rested it on top of mine, squeezing lightly. “Everybody gets scared before marriage.”

“Yeah, you’re right.”

“So have an affair.” Her smile was playful, her voice matter-of-fact. “Men do it all the time. They get jittery before they’re supposed to get married, so they find some bimbo to screw. Have you thought of that?” She grinned; her gap looked large enough to walk through.

“Now you really are insane.” I stood up, holding the tray. “Listen, I’d love to sit here and continue this crazy talk, but I have a meeting with Lucia in ten minutes and I’m not too prepared.”

“It doesn’t matter, it’s more important to look pretty. Here, put on some lipstick.” Mae pulled a tube from her purse and pushed it toward me. “You ate off whatever you applied earlier to try to impress your ho in chief.” Mae couldn’t stand Lucia.

“That wasn’t for her, that was for you, silly.” I went around the table and kissed the top of her head, before tugging my own lipstick from my pocket.