Читать книгу The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: How a Remarkable Woman Crossed Seas and Empires to Become Part of World History - Linda Colley - Страница 11

Herself

ОглавлениеI first came across Elizabeth Marsh while writing my previous book, Captives. To begin with, I was aware only of the Mediterranean portion of her life; and it was not until I began investigating the background to this that I gradually uncovered the other geographies of her story. I learnt that a Californian library possessed an Indian travel journal in her hand, and an early manuscript version of her book on Morocco. Then I came across archives revealing her links with Jamaica and East Florida. Further searches turned up connections between her and her family and locations in Spain, Italy, the Shetlands, Central America, coastal China, New South Wales, Java, Persia, the Philippines, and more.

That this international paper chase proved possible and profitable was itself, I gradually came to realize, a further indication of some of the changes through which this woman had lived. Elizabeth Marsh was socially obscure, sometimes impoverished, and elusively mobile. In the ancient, medieval and early modern world, such individuals, especially if they were female, rarely left any extensive mark on the archives unless they had the misfortune to be caught up in some particular catastrophic event: a trial for murder or heresy, say, or a major rebellion, or a massacre, or a conspiracy, or a slaver’s voyage. That Elizabeth Marsh and her connections, by contrast, can be tracked in libraries and archives, not just at interludes and in times of crisis, but for most of her life, is due in part to some of the transitions that accompanied it. During her lifetime, states and empires, with their proliferating arrays of consuls, administrators, clerks, diplomats, ships’ captains, interpreters, cartographers, missionaries and spies, together with transcontinental organizations such as the East India Company, became more eager, and more able, to monitor and record the lives of ‘small’ people – even, sometimes, female people – wherever they went.

Recovering the life-parts and body-parts of Elizabeth Marsh has been rendered possible also by the explosion in global communications that is occurring now, in our own lifetimes. The coming of the worldwide web means that historians (and anyone else) can investigate manuscript and library catalogues, online documents and genealogical websites from different parts of the world to an extent that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago. At present, this revolution – like so much else – is still biased in favour of the more affluent regions of the world. Even so, it is far easier than it used to be to track down a life of this sort, which repeatedly crossed over different geographical and political boundaries. The ongoing impact of this information explosion on the envisaging of history, and on the nature of biography, will only expand in the future.9

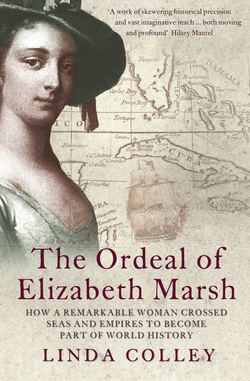

To say that Elizabeth Marsh’s life and ordeal are recoverable, and that this in itself is eloquent about closer global connections in her time and in ours, is not the same as saying that the sources about her are abundant or easily yielding. To be sure, this was a woman who was addicted to writing. Even when (perhaps particularly when) she was confined to the lower decks of a store ship on the Indian Ocean, or in a Moroccan prison, she is known to have busied herself writing letters. Neither these, nor any other letters by her survive. Nor do any personal letters by her husband or parents survive, or any that might compensate for the lack of a portrait of her, by closely detailing her appearance. The colour of Elizabeth Marsh’s eyes and hair, like her height and the timbre of her voice, and the way she moved, remains, at least at present, beyond knowing. So does how she and others perceived exactly the colour of her skin.

This absence of some of the basic information which biographers can normally take for granted is partly why I have chosen to refer to Elizabeth Marsh often by her whole name, and sometimes only by her surname. Mainly for the sake of clarity, but also because of how she lived, I also refer to her only by her unmarried name. So in these pages she is always Elizabeth Marsh, never Elizabeth Crisp. The practice of always referring to female characters in biographies by their first names can have an infantilizing effect. It also suggests a degree of cosy familiarity that – as far as this woman is concerned – would be more than usually spurious. Certain aspects of her life and mind, as of her appearance, are unlikely ever to be properly known; though the impact she was able at intervals to make on others is abundantly clear.

What has survived to convey her quality and her actions over time are a striking set of journals, scrapbooks and sagas, compiled by her and by some members of her family. There are Elizabeth Marsh’s own Moroccan and Indian writings. Her younger brother, John Marsh, produced a memoir of his career. Her uncle, George Marsh, assembled a remarkable two-hundred-page book about himself and his relations and two commonplace books, and devoted journals to the more significant episodes in his life. Ostensibly concerned with personal and family happenings, achievements and disasters, these miscellaneous chronicles can be read also as allegories of much wider changes. Even some of the maps drawn by Elizabeth Marsh’s father contain more than their obvious levels of meaning. I have drawn repeatedly on these various family texts in order to decipher this half-hidden woman’s shifting ideas, emotions and ambitions.

Attempting this is essential because, although she undoubtedly viewed certain phases of her life as an ordeal, Marsh rarely presented herself straightforwardly as a victim. It was her own actions and plans, and not just the vulnerabilities attaching to her marginal status, the occupations and mishaps of her male relations, the chronology of her life, and the country and empire to which she was formally attached, that rendered her at intervals so mobile, and exposed her so ruthlessly to events. In particular, without attending closely to these private and family writings, it would be hard to make sense of five occasions – in 1756, in 1769, in 1770–71, in 1774–76, and again after 1777 – on which, to differing degrees, Elizabeth Marsh broke away from conventional ties of family and female duty, only to become still more vividly entangled in processes and politics spanning continents and oceans.