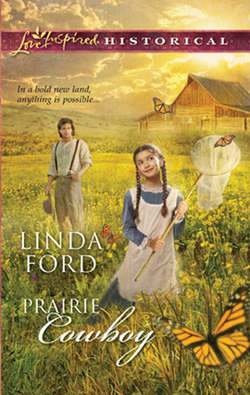

Читать книгу Prairie Cowboy - Linda Ford - Страница 8

Chapter One

ОглавлениеDakota Territory, 1886

Her dream was about to come true in living, vibrant color.

In a few minutes she would welcome her first class of students. Eighteen-year-old Virnie White stood in the doorway of the brave little white schoolhouse and watched the children arriving in the schoolyard. The brittle yellow grass had been shaved by one of the fathers and the children’s feet kicked up soft puffs of dusty mown grass.

A horse entered the gate of the sagging page wire fence. The rider, a man, reached behind him. A child grabbed his arm and dropped to the ground.

The boy wore overalls that looked as if the only iron to touch them had been a hot wind. He wore a floppy hat that did little to hide the mop of wild brown curls. He needed to be introduced to a pair of scissors.

Virnie expected the father to ride away as soon as the boy got to his feet but he hesitated, glancing about until he saw her in the doorway. She felt his demanding look and gathered her skirts in one hand and hurried across the yard. He dismounted at her approach. She held out her hand to the black-haired man. “Miss Virnie White, the new teacher.”

He took her hand in his large, work-worn grasp and squeezed. “Conor Russell.”

She pulled her hand to her side. “And this is…?” The boy raced over to join the boys in kicking around a lump of sod.

“Ray.”

“How old is Ray?”

“Eight.”

At the note of longing in the man’s voice, Virnie turned. His gaze followed his son, concern evident in the tense lines around his eyes and the way he pressed his lips together. She studied him more closely. A handsome man with thick black hair that needed trimming almost as much as his son’s, eyebrows as black as his hair, and dark blue eyes that shifted toward her, giving her a look as full of challenge as the superintendent had given at her interview.

She lifted her chin, clasped her hands together and met the man’s look without flinching.

“Ray…well, Ray is…” He shifted his gaze past her to the men in the wheat field bordering the schoolyard.

She’d watched them earlier as they tossed stooks into the wagon and had breathed in the delightful nutty scent of ripe grain.

“What I’m trying to say is Ray’s mother is dead.”

One thought vibrated through her brain. A widowed father who cared about his child. She wanted to squeeze his hand and tell him how noble and wonderful he was. But the knowledge of his concern picked at a brittle scar and somewhere behind her heart a tear formed. Willing herself to ignore the place that held those hurtful things, she tipped her chin higher. Her lips felt stiff as she spoke. “Mr. Russell, rest assured I shall treat Ray with kindness and fairness.” As she intended to treat all the children.

He touched the brim of his hat in a gentlemanly expression that made her feel she had given him the assurance he needed. “I hope so.” He swung back into the saddle and kicked his horse forward, urging the animal to a gallop as soon as he left the schoolyard.

She stared across the field to where the men worked. The creak of the wagon as it groaned under the weight of stooks made little impression on her conscious thoughts.

Four little boys, Ray among them, raced past her chasing the steadily shrinking clump of sod. Did the child realize how fortunate he was? But then he was a boy. Obviously not the same thing to deal with as a motherless girl.

Virnie pulled herself back from the ghost of her past and with clipped steps headed for the schoolhouse. She glanced at the empty bell turret. How pleasant it would be to ring a large bell by means of a rope, but the community could not yet afford one so instead she picked up a hand bell from the step where she’d left it.

At its ringing, the children hurried toward her.

“Girls on my right. Boys on my left.”

They quickly sorted themselves out except for Karl and Max who didn’t appear to understand English.

She went to the pair and pointed them toward the boys’ line. She counted the boys—only eight and she knew at last count there were nine boys and eight girls. She checked the girls’ line and immediately saw the problem.

“Ray, the boys are in this line.”

Several of the children tittered and Ray shot her a blazing look.

Hilda, twelve and the oldest Morgan girl, leaned over and whispered. “Ray is a girl. Rachael Russell. It’s just her pa doesn’t know what to do with a little girl.”

Shock burned through her veins as hot and furious as the prairie fires she’d read about with a shiver of fear. Her vision alternated between red and black. She feared she would collapse. No. She couldn’t do that. Not on her first day of being a better-than-average teacher. She sucked in a breath, amazed the rush of air did nothing to dispel her dizziness. She knew firsthand how it felt to have your father wish you were a boy. Her father had gone so far as to say it. “Too bad you weren’t a boy. Would have made life simpler.”

How could she have run so forcibly into such a blatant, painful reminder of her past? A past she had vowed to completely forget? And she would forget it.

Miss Price had rescued her, taught her to be a lady, and modeled how to be a good teacher. She was here to emulate Miss Price.

Lord God, give strength to my limbs and forgetfulness to my thoughts.

She straightened her spine and went to the little girl. “Rachael, what a beautiful name. I’m sorry for my mistake.”

The child ducked her head, hiding her face beneath the brim of her hat.

Virnie gently removed the hat. Her eyes widened as a wave of brown curls fell midway down the child’s back. “Why, what beautiful hair you have.”

Rachael sent her a shy look of appreciation.

Something in the child’s eyes went straight to Virnie’s heart and pulled the scab completely from her wound. Her past stared at her through the eyes of Rachael Russell. And in that heartbeat of time, Virnie knew she had come to Sterling, North Dakota, for a reason as noble and necessary as teaching pioneer children. She had set her thoughts to becoming a dedicated teacher who found ways to challenge each student to do his or her best. Those who needed the most help would be her special concern. Those who excelled would receive all the encouragement she could provide. She’d make Miss Price proud of her by imitating her noble character as a teacher.

But just as Miss Price had done seven years ago when she saw Virnie’s need and reached out to help her, she’d repeat the way Miss Price had helped her by reaching out to Rachael and perhaps repay her by doing so.

Her mind made up, she welcomed the children and had them march inside where she proceeded to get them into grades according to some rudimentary testing. Karl and Max Schmidt were problems. She couldn’t test them when the only things they said were, “My name is Karl,” or, “My name is Max,” and, “Please.” But here was her first challenge. Teach these two to communicate in English.

Correction. Her second challenge. Rachael was her first.

During the lunch break, she whispered to Hilda that Rachael’s hair would look beautiful brushed. She gave Hilda ribbons. Hilda smiled and nodded. A bright girl. And before the lunch break ended, she’d fixed Rachael’s hair and so no one would realize it was for her benefit, she redid her two little sisters’ hair as well.

When the school day ended and Virnie dismissed the children, Rachael hung back waiting for the others to leave before she sidled up to Virnie.

“Teacher, thank you for the ribbons.”

Virnie touched Rachael’s head. “I don’t need them any longer. You enjoy them.”

“I will.” She raced outdoors.

Virnie followed.

Conor had no call to get Rae. She was perfectly capable of finding her way home. Had for two years now. But he wanted to see the new schoolmarm again. All day her face had filled his thoughts. Was she really as pretty as his memories said? He muttered mocking words. He knew pretty was useless out here. How did it help anyone create a solid home?

It seemed all the other children had left but he waited on horseback for Rae to exit. She ran out, the new school teacher at her heels.

Yup. Just as pretty as he recalled. Her hair was a doe-soft brown and pulled back into a bun. He couldn’t say for sure if her eyes were brown, only that they were dark and watchful and this morning he’d decided she had a kind look. Soft, too. He could tell just looking at her. He’d give her a month, two at the most, before she found life a little too much work on the wild prairie and turned tail and ran. Took a special woman to survive frontier life and Miss White didn’t have the hardy look at all.

Without even glancing at Rae, he reached down and pulled her up behind him then touched the brim of his hat by way of greeting to the schoolmarm. As he tugged the reins and left the schoolyard he wondered why she gave him such a disapproving look.

“How was your day?” he asked his daughter.

“Good.”

“You like the new teacher?”

“Yeah, Pa.”

He didn’t say more as he thought of that pretty new teacher. Now if they were back East, living in relative comfort, he might just think about courting the young woman. But he wouldn’t be thinking another such foolish thought. Two months, he decided. She wouldn’t last a day longer than that. Too many challenges. Like… “How did she manage the Schmidt boys?”

The family had been in the community only a few months. John, the father, could barely make himself understood and he knew Mrs. Schmidt spoke not one word of English.

“Miss White taught them lots already. She said we must all help them. When George said he didn’t come to play mama to some foreigner, Miss White said she would tolerate no unkindness.”

Conor grunted. He knew George Crome. A big lad. It surprised him George’s father hadn’t kept him home to help with harvest, but then the Cromes weren’t exactly suited to farming. They seemed to think the work would take care of itself. He imagined the way George would lift his nose and sniff at having to help two small boys. “What did George do?”

“At first he growled but Miss White reminded us we are all newcomers. Wouldn’t we want people to help us?”

Sounded like a smart woman.

They neared the Faulks’ property and a big brute of a dog raced toward them, barking and snarling. “I see Devin is visiting his folks.” The dog belonged to the grown Faulk boy who wandered in and out at will. Conor turned the horse to face the dog and shouted, “Stop. Go back.”

The dog halted, his hackles raised, his lips rolled back to reveal his vicious teeth. But he didn’t advance.

Rae’s fist clutched at his shirt as if she thought the horse would rear and she might fall.

“Noble isn’t about to let an old dog make him act crazy.”

Her fingers uncurled. “Yeah, I know.” She sounded a little uncertain.

“You aren’t scared of that old dog, are ya?”

“Nah.”

“Good, because he’s nothing but hot air and bluff.”

They resumed their journey and his thoughts slid uninvited and unwelcome back to the schoolmarm. Rae’s mind must have made the same journey because she resumed talking about the day.

“Miss White asked George what his best subject was. He’s very good at arithmetic. Miss White gave him all sorts of problems to solve and he did them all. Miss White said he needed to cap’lize on his strengths. Pa, what does cap’lize mean?”

He grinned, picturing little Miss White finding a way to make George feel good after a scolding.

“Capitalize means to make the most of something.”

“I like Miss White.” Rae’s voice was soft, filled with awe.

Conor’s skin prickled. He knew his little daughter missed having a mother. But she would only be hurt if she looked for a substitute.

“I hope she stays.”

Best to make Rae face the truth. But he wanted to spare her pain. Maybe with a little help she would figure it out herself. “You think she will?”

“She’s smart.”

“Uh-huh. But is she tough?”

“She’s awfully pretty.”

He squeezed the reins until they dug into his palm. He’d endured enough pain and disappointment with pretty women. So had Rae. Best she face facts and deal with them. “Now, Rae, how many times have I told you what use is pretty?”

“Yeah, Pa. I know. A person has to be strong to survive.”

“Don’t you be forgetting it.” They turned toward their little house. This was where they belonged. He would fight to keep this place. He’d teach Rae to deal with the hardships. “You go on in while I unsaddle Noble.”

A few minutes later he returned to the house, intent on getting a drink of water before he resumed working. Rae stood peering into the cracked mirror over the washstand. She turned as she heard him enter and grinned, waiting for him to admire her hair.

He felt like someone whacked him alongside the head with a big old plank. Oh, how she looked like her mother. “Hair ribbons.” Pretty stuff. Useless stuff. The sort of thing that made women pine for a life that wasn’t possible out here. People—men and women alike and children, too—had to forget the ease of life back East where supplies were around the corner, help and company across the fence and being pretty and stylish mattered. Out here survival mattered and woe to anyone who forgot. Or pined for things to be different. His wife had done the latter. She’d willingly left the comfort of Kansas City to follow his dream of owning land but she’d been unprepared for the challenges. In the end, she’d let them defeat her. She got a cold that turned fatal because she didn’t have the will to live. “Where did you get them?” His mouth felt gritty.

“Miss White gave them to me. And Hilda did my hair.” Her eyes were awash with hope and longing.

He could allow this tiny bit of joy. But no. He must not allow weakness in himself any more than he could allow it in Rae. “Tomorrow we give them back.”

“Pa.” Pleading made her drag out the syllable.

“How many times have I told you? Only the strong survive out here. You want to survive or don’t you?”

“Yes, Pa.”

“You and me are going to make ourselves a home out here. Now aren’t we?”

“That’s right, Pa.”

“Then put the ribbons aside before they get dirty and tend to your chores.”

She nodded. In her eyes determination replaced hope. And how that hurt him. But he had to be strong for the both of them. She pulled off the ribbons, rolled them neatly and put them beside her lunch bucket.

“There’s hours of daylight left. I’ve got to get the crop cut and stooked. Uncle Gabe will be coming any day.” He and Gabe helped each other. “I won’t be back until dark. You know what to do. Think you can handle it?”

She tossed him a scoffing look. “I can handle it. You know it.”

He pulled her against his hip for a quick hug. “Proud of you, Rae.”

“You’ll come in and say good night when you get home? Even if I’m sleeping.”

“Always. You can see me from the yard. If you need me all you have to do is bang on the old barrel.”

“I know.”

He hated to leave her although he’d been doing so longer than he cared to think about. Since Irene had laid down and quit living more than two years ago, leaving him to raise Rae on his own. But he didn’t have much choice. The work did not do itself, contrary to the hopes of men such as Mr. Crome.

He turned and headed for the field as Rae went to gather eggs.

It was dark when he returned. He searched the kitchen for something to eat and settled for a jam sandwich. He wiped dried jam from a knife in order to use it. They were about out of dishes fit to eat from. He’d have to see if Rae would wash a few. He’d also have to find time to go see Mrs. Jones who sold him his weekly supply of bread.

Rae had dumped out her lunch bucket in preparation for tomorrow’s food. The hair ribbons lay on the lid.

Miss White would no doubt look all distressed when he returned the ribbons and set her straight about what was best for Rae. He could imagine her floundering as she tried to apologize. Best she learn life here was tough.

Maybe she could return to her safe home back wherever she’d come from. Before she had to endure the harshness of a Dakota winter.

Yet he felt no satisfaction at knowing he would be among those who drove Miss White away. And his regret made him want to kick himself seven ways to Sunday. He knew better than most the folly of subjecting a pretty woman to the barren pioneer life.

He checked on Rae. She slept in her shirt, her overalls bunched up on the floor beside the bed. Dirty clothes lay scattered across the floor. He didn’t have time to do laundry until after harvest.

He pulled the covers around Rae and stood watching her for a few minutes. He would never understand how Irene could give up on life. He thought she shared his goal. Having grown up in Kansas City with a father who went from one job to another and took the family from one poor hovel to the next, he’d vowed to provide for himself and his family a safe, permanent home even if he had to wrench it from this reluctant land with his bare fists. He would let nothing stand in his way. Not weakness. Certainly not a hankering after silly, useless, pretty things. Rae’s mother should have fought. For Rae if not other reasons. He renewed his daily vow to make sure Rae had a safe and permanent home.