Читать книгу The Unsolved Oak Island Mystery 3-Book Bundle - Lionel and Patricia Fanthorpe - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Logical Connections CHAPTER 2

ОглавлениеSome find it difficult to imagine how my parents, who lived the carnival life and rode motorcycles, could end up digging for treasure. Yet it was a logical progression. Everything about them — their values, their skills, their strengths, and even their weaknesses — made them just the right candidates for the big adventure of Oak Island.

Let me give a clearer picture of our off-the-road life. My parents went with the carnival each spring, but in the fall, they came back, flush with money and eager to set about their other, very different lives.

In those days, the carnival was open from ten in the morning to after midnight six days a week. On Sundays the show train wound its way from city to city, while performers caught a break. But for the most part, travelling with the carnival meant four or five months of a relentless grind in sweltering heat, stormy wind, soaking rain, or cold so intense that fingers fumbled with tickets and money.

After the Canadian National Exhibition, which, except for Sundays, was a two-week stretch of eighteen-hour days, the show travelled through a series of fall fairs in towns such as Leamington, Ontario, or Trois-Rivières, Quebec, until heavy rain and bitter cold, the harbingers of winter, kept spectators away. Then the show wound its way back to storage in Brantford to hibernate until the following spring. Performers and concessionaires were exhausted. Many would head south for the winter or go to home bases across Canada.

Mom and Dad would come back from a summer on the road, tired and very thin, the result of having shaken pounds off all summer racing their motorcycles round and round inside the Globe of Death. For their efforts they would have a few extra thousand dollars to pay some bills and buy a big-ticket item or two, like a sewing machine, refrigerator, or new furnace. But no holiday was on their agenda. Instead, Dad immediately went to work as a plumber/steamfitter for Stelco, Hamilton’s mammoth steel plant.

Our summer lives consisted of Mom and Dad on the road and Bobby and I living with our great-uncles and great-aunt. Our winter lives consisted of Dad working for Stelco, Mom running the household, and I (and later Bobby) attending Memorial Public School just two blocks away. Life, as far as I was concerned, was perfect. We had distinctly different summer and winter lives. We had a permanent home. Our lives were stable but far from dull. Something was going on all the time, and we all were happy partners in it.

Dad worked at Stelco full-time, but he always had other projects in the works that we all believed would someday make our lives better. We lived on the ground floor of a three-storey brick house in Hamilton; Dad worked on weekends and evenings to build two apartments above us to provide a bit of extra income. He also designed carnival rides and built them in the backyard. One was called the Ski Lift; it gave your heart a little lift each time you swooped down from the top. Several other adult rides and quite a number of kiddie rides followed.

Dad was great at figuring ways to use commonly available parts, like vehicle axles, gears, and sprockets, instead of expensive custom-made parts. Nevertheless, carnival rides were costly to construct, and any money that was realized from them was immediately plowed right back into whatever came next. Ideas for new rides came quicker than the money to finance them. I remember the dismay Bobby and I experienced after struggling valiantly to help Dad complete a ride, only to see him tighten the last nut, take pictures, then immediately set about tearing it down to cannibalize it and use the parts for his next ride, which he promised would be even better.

The whole family was involved in his enterprises. Using a steel brush, Bobby and I scrubbed the rust off of his latest ride and Mom climbed up and applied the silver undercoat, then the enamel final coat. Whatever the project, we were all in it together.

I’ll never forget one winter when Dad spent all his spare time at a table in the corner of the living room, with pen and India ink, making meticulous drawings for patent applications; a folding boat was one project, some new kind of bathtub was another. Someone bumped the table and the India ink fell on the new living room rug. I expected an ear-splitting shriek from Mom, but not a sound. Then Dad quietly said, “Milk might work.” Immediately all four of us were on our hands and knees with a big bowl full of milk, scrubbing the rug like mad. Not another word was uttered until the job was done. Then we shared a good laugh while admiring our handiwork.

When Dad was occupied with segments of projects that only he could work on, the rest of us kept busy in other ways. Mom played the piano or sewed while Bobby and I spent our time drawing, making models, or developing other skills for the fantastic futures we planned.

Dad’s projects weren’t hobbies. They were always something that, if successful, would free him from Stelco and benefit us all. It wasn’t that he didn’t like plumbing and steamfitting, but he felt a life working for others was a life wasted. Dad dreamed of being free of daily constraints so that he could devote himself totally to his inventions and projects.

I remember coming home one day and telling him I’d just met our next-door neighbour in the fabric store downtown, where she was working. She had told me that she didn’t need the money, but now that she was a widow what else was there for her to do with her time. Dad looked at me sombrely and said, “Imagine having so little creativity that you have to get a job for excitement.” We both shook our heads piously. Lack of creativity would never be our problem.

At home I learned that work can be fun and that it is great to always be working towards something. But Sundays were different. Sunday dinner, the best meal of our week, was served around noon, then the family piled into the car and away we went on a mystery tour. Dad kept the destination a secret, letting it slowly reveal itself as the journey progressed. Sometimes we visited Grimsby or Jordan to see the beautiful cherry blossoms, or to Hamilton’s Rock Garden, or maybe Niagara Falls. Sometimes we carried our aluminum boat on the roof of the car and launched it in Lake Ontario at Van Wagner’s Beach. Then we’d slowly putt along the shoreline for miles. Not having a lot of faith in our little craft, Mom, Bobby, and I nagged Dad to keep close to shore so we could swim in if anything went wrong. It never did. In winter we often went tobogganing or ice skating on the Back Bay. Whatever the adventure, at the end of the day, we always hurried home in time to huddle together in the dark, on the living room carpet, with a sandwich supper, sharing our once-a-week treat of Canada Dry ginger ale or Orange Crush, listening intently to Lamont Cranston and The Shadow on the radio.

We were a happy lot. Mealtimes were great times in my family; everyone shared hopes, dreams, and recitations of daily foibles. Conversations were cheerful, optimistic, and revolved exclusively around the present or the future. No crying over spilt milk, no gossip or negative talk. Not that we were all that virtuous; more likely we were so egocentric that the only topic of conversation that stood a chance was us. Ours was a family of laughter and high hopes, where the most precious thing of all was time. Dad was the one who set that tone.

But he didn’t mind indulging in a bit of dreaming. Many times he would smile and begin, “When our ship comes in …,” and then he’d spin some fantastic dream like “Your mother and I will have his and hers Cadillac convertibles” or “We’ll throw away the old washing machine in the basement and send all our laundry out.” Time after time he would draw us through these little imaginary journeys. We’d all listen, spellbound.

Mom always said that she would be satisfied with very little, and that it was Dad who had the grandiose plans for wealth. I believe that’s true. But it always made her smile when he started his “When our ship comes in” talk.

We all believed that Dad was a genius. Time and again he proved he could put together whatever was needed out of the most unlikely everyday materials. He could fix anything structural or mechanical, any kind of engine. He took care of things for us, and he was always ready to help a friend. He knew working parts and he knew the principles behind them — hydraulics, magnets, generators.

Dad read a lot. He was unable to pass by a newspaper without reading at least a snippet of it. I remember waking on a school day one morning and being amazed to find Dad sitting at the kitchen table reading a newspaper.

“Aren’t you going to work today?” I asked.

“Yes, but I was going to be ten minutes late and they dock you a half-hour, even if you’re only late five minutes. I thought I’d just read a bit and go in on time for the half-an-hour late,” he said. Some time later, when I began getting my breakfast ready, he was still there. “I was so engrossed in my reading I missed the half-hour, so I thought I’d just read a bit more and go in for the one-hour late,” he explained. Half an hour later, on my way out the door to school, he was still in the kitchen but no longer reading; now he stood, noisily gathering his things together.

“Waiting for the hour-and-a-half late?” I asked innocently.

“No!” he retorted. “I’m going to work. If I keep reading, I’ll never get to work at all.”

Dad’s interests were far-ranging. He owned the complete eight-volume set of Bernard McFadden’s Encyclopedia of Naturopathic Remedies. 'Mention an ache or pain and Dad could suggest the cure. Talk about air travel and he could launch into the history of flight and finish with whatever exciting advancements were on the drawing boards now. He kept track of anthropological and archeological discoveries and developments in technology and mechanics. He read the newspaper from cover to cover every day; he read construction, mechanics, health, and science magazines, as well as anything else he could get his hands on. More importantly, he remembered everything he read. This was the early 1940s. There was no nuclear physics, stem cell research, or any of the myriad highly technical scientific specialties that now exist. Dad knew the answers to all the questions that touched our lives. As far as Mom, Bobby, or I were concerned, he knew everything.

Dad grew up in the era of the self-made man. Men like Henry Ford started with nothing but determination and ingenuity and became fabulous success stories. Ahearn, Bell, Howe, Marconi, and others who invented things or used their creativity to think of new ways to use existing things were setting themselves apart from the crowd. In fact, at that time most of Canada’s new wealth was generated by inventors and entrepreneurs working alone. It was possible to go from having nothing to having it all, and you could do it solo. Dad saw himself in that league.

Dad’s good nature was magnetic. The moment he came in the door each day after work, he would sing out “I’m home!” and everybody would run to say hello. He was such a cheerful, optimistic person, the room brightened whenever he entered.

Many of our car rides included a sing-along. In a good strong voice Dad would belt out a robust beginning to a song and we’d all join in, but before long the song would falter for lack of words. Just before it gave its last gasp, Dad would loop it back to the beginning, drawing us with him, and round we’d go again, with great gusto. In that way, one song lasted the duration of a trip. “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen” was a favourite. Dad sang it to alleviate Mom’s yearning for England. At first that pleased her, but after years of the loop treatment, he needed only to sing the first line to elicit groans of despair from her.

I thought Dad was not only the smartest man alive, but also the most patient, kind, and all-round wonderful. He never lost his temper, never raised his voice except in laughter or song. He was not critical; he focused on the good. He was observant. If he noticed that you weren’t happy he’d comment on it out loud, so everyone knew what everybody else was feeling. I remember one spring when Mom spent day after day pacing irritably back and forth in front of the living room window, concentrating deeply on thoughts she wasn’t sharing, acting very much like a caged, angry animal. Bobby and I cringed. Finally Dad declared, “It’s spring. Your mother has had enough of this home life. She’s restless to get on the road again.”

Of course he was right. Mom was a performer, an entertainer, a star. Domestic chores were always a struggle. Her Sunday roasts were magnificent, but weekday meals confounded her. Fried Spam or hamburger patties with boiled potatoes made frequent appearances at our table. She tried to be more adventurous, but those attempts yielded little success. Once she slaved away all afternoon over some “mock duck” concoction gleaned from a magazine: in reality it was hammered flank steak, tough as shoe leather, rolled around bread stuffing. Too polite to criticize, we feigned delight and struggled to saw our way through it.

Vegetables in my home were mashed potatoes, canned peas, canned corn, or canned lima beans. I learned to detest them all, save the potatoes. Dessert was always pudding or canned fruit. No cakes or cookies ever came out from Mom’s oven. She never learned to bake.

But then, what would you expect from a dancer-cum-motorcyclist? Surely it was not a future of domestic bliss that attracted my mother to my father.

Anyway, my mother had lots of talents in other aspects of domestic life. She certainly was good at sewing. After she fought her way through her first project, living room drapes, there was no stopping her. She made all kinds of clothing, from cowboy shirts to tailored suits. And nothing looked homemade.

She played piano surprisingly well. She taught herself to read music, and eventually between hard work and her exceptional ear for music she was able play even complicated arrangements of popular or classical pieces. Rachmaninoff’s Prelude, Rustle of Spring, Deep Purple, and the boogie-woogie version of Flight of the Bumble-Bee come to mind.

She read voraciously, mostly fiction, especially science fiction. And she was a great storyteller. I remember once leaving the house just as my friend Shirley arrived. I explained I was on my way out and Shirley said, “Oh, that’s okay. I really came to visit your mother anyway. I was hoping she’d tell me one of her stories.”

Mom was good at handling money. When they travelled with the globe she always managed to surreptitiously sneak some money aside. At the end of the year she would have quite a little nest egg. But it was not for herself. Sooner or later Dad would find himself in a financial bind, and, to his relief, out would pop the secret stash. In Hamilton, she ran the household on rents from the apartments upstairs, and she could always manage to accumulate a little private cache of money. Come some unforeseen expense, we would be rescued again.

Dad was quick to give Mom credit for her ability to come to our rescue. But he must have thought the money came by magic, for after they stopped using the globe and we no longer had rental apartments, Dad still came to her, hat in hand, for unexpected expenses like income tax, and he seemed mystified when she had nothing to give. Surely only my father would find income tax to be an unexpected expense year after year.

Mom was around seventeen when she met Dad; he was eight years older, handsome, and a world traveller. Mom was always his biggest fan. She could disagree vociferously with Dad, but if anyone else tried, she would spring to his defence. And you could see, day in and day out, how happy she was in her life with him. They constantly showed each other affection, laughed together a lot, and obviously preferred being in each other’s company.

They talked everything over; Dad valued Mom’s opinion. And always, throughout their lives, they arranged to do some things together. In Hamilton they had their own small street motorcycles, and on many evenings they would go for a spin together at dusk, purring down the quiet side streets of Hamilton. They cherished their time alone.

However, they were not always lovebirds. They had fierce arguments, but the fierceness was all on Mom’s part. She had a fiery temper. When something displeased her, she’d rant and rave, while Dad, always the peace-maker, murmured in the background, “There, there Mildred.” Suddenly she would announce that she was leaving, cram some clothes into a suitcase, and storm out of the house and down the street. Dad would follow, imploring her to return. Bobby and I would tremble. Eventually, they would return, silently unpack the suitcase, and spend some private time together. After that, peace and happiness would reign once more.

When I was an adult Mom once confided in me about these episodes. “I got sick and tired of packing. I knew I’d soon be unpacking again. Eventually I stopped packing altogether. I just left. Once I stormed out of the house, marched along Main Street, and got on a streetcar. The door closed and then Bob rushed up to the glass door and started rapping on it,” she told me. “I urged the conductor, ‘Don’t let him on! Don’t let him on!’ Bob kept rapping. The poor conductor didn’t know what to do. He said, ‘Lady, I can’t just ignore a customer. I’ve got to let him on.’ Eventually I gave in, he let Bob on, then we got off the streetcar together and walked home, holding hands. I guess the people on the streetcar thought we were crazy.”

Mom once told me another suitcase story. She and Dad were in a small Ontario town with the carnival one evening when one of their spats erupted. In a fury, Mom packed up, raged out of their hotel room, and marched resolutely down the street, suitcase in hand. A car driving down the street in her direction slowed beside her, and a man wound down his window and quietly called to her, “Five dollars for five minutes?” Stunned for a moment, she recovered and retorted, “Bugger off!” then sharply turned and marched back to the hotel and the safety of married life. That may have been the moment when she gave up packing.

With all that activity going on around our house — a married couple riding out on dual motorcycles, carnival rides being constructed in the backyard, the house assuming constantly changing dimensions — it’s not surprising that our neighbours looked on us with a mixture of bewilderment and envy.

Occasionally I had friends whose parents wouldn’t allow them to come to my house. It was the show business connection. When I told my mother, she exploded. “These people are nothing! We are infinitely superior to these small-minded bigots who have never even been out of their own country. We are cultured, knowledgeable, well-travelled, and well-read.” Somewhat chastened, I tried to keep all of that in mind.

For the most part, we were impervious to what other people thought. They knew nothing. We never had visitors, other than show people, and then only once or twice a year. We never had company for dinner. Only once do I remember my parents attending a parent-teacher night for Bobby and me. We were completely insular.

One winter, Dad decided not to return to Stelco. He ran his own plumbing and heating business for about two years. Quickly it became clear that he was pretty good at getting work, very good at doing the work, and abysmal at collecting the money. And when he ran his own business, his evenings and weekends were totally absorbed by that. No time for inventions or for building carnival rides. He hated that. He felt more a prisoner of his own business than he ever had at Stelco. Around that time my parents also quit travelling with the carnival. They played only the Exhibition and fall fairs. Then they stopped even that.

Bobby was ten and I was sixteen in 1951 when Rick made his appearance. He might as well have had four parents. We all loved him to death. But by the time Rick was three, I was gone from the home, so I’m not part of his memories of childhood. And on top of that, when we try to compare notes, it is clear that the parents I recall from my early years bear no resemblance to the parents Rick had.

Priorities changed. I think I can even remember the turning point for Dad. One evening in Hamilton, in the winter that Rick was born, I was watching through our living room window to the street where a blizzard was raging and a man’s car was stuck in the snow. He tried to drive forward; he tried to drive back; he tried to shovel; he tried to push. Nothing worked. Mom took a look too, and then Dad walked into the living room and stood beside us, looking out the window. I remarked that guy sure could use a push. Dad was silent for a while, then said, “Well, yes, he could use a push, but I’ve been thinking … that’s the problem with me, I spend too much time giving pushes, and if I keep spending my time and energy giving a push here and there instead of concentrating on my own projects, I’ll never get anywhere.” Mom and I were incredulous. We flounced out of the room and didn’t speak to Dad all evening.

It was a remarkable change. As time went by, Dad became ever more preoccupied with his projects. Our beautiful Sunday mystery tours faded into memory.

Shortly after Rick’s birth, we sold the house in Hamilton so that Dad could build one in Stoney Creek. It was a beautiful, big, modern house with real ceramic tile in the bathroom and a basement with a walkout to ground level overlooking a ravine. Mom and I loved it. Dad kept saying, “Don’t get attached to it. We’re building it for sale.” I think he had aspirations to become a full-time house builder.

In between work that kept food on the table, it took Dad about two years to complete that house. Or should I say, Mom and Dad? She held this while he hammered that. When it was time to paint the exterior, two stories front, three stories rear, Dad built a scaffold and Mom swung up and painted, ever the helpmate.

They barely got that house finished and sold before they decided to give the Globe of Death another try. They hadn’t ridden in it for four years. It was during their first month back that they had their only other accident. Mom said she could hear Dad riding too fast; he was too close behind her. She went faster; Dad sped up. Mom went even faster; so did Dad. Mom said she couldn’t figure out what was going on; it was as if he had lost his sense of timing. Finally Dad’s motorcycle clipped Mom’s rear wheel. Fortunately, she fell not into the centre of the globe but against the side. She slid down to the bottom, where her motorcycle lay waiting with wheels spinning. Although badly bruised and stiff for weeks, she fortunately sustained no serious injury.

They completed the year without further mishap. During the following season, Bobby, now sixteen, joined them, learning to ride a motorcycle for the Front. However, Mom and Dad found they no longer enjoyed carnival life. It was a grind.

Then they had a stroke of good fortune. In Quebec City, their last spot of the season, Sam Pollack of Pollack Brothers Circus caught their act and offered them star billing to tour the United States with the Globe of Death. They were thrilled. This would be the crowning achievement of their careers.

They had been riding motorcycles with the carnival for years, but carnivals and circuses are very different. A circus consists of a number of acts that appear together under one roof, or big top, with everyone under contract for so many months for so many dollars to circus proprietors. Circus management sets the standards and the tone for the entire show. On the other hand, a carnival is a travelling collection of rides, shows, and concessions, some owned by show management, others by independent operators who give a percentage of their take to show bosses.

One big difference between carnivals and circuses lies in the expertise of the performers. While one act or another in a carnival may require some skill, in the circus, all performers are highly trained. Top billing in a circus means you are the main attraction among many very accomplished acts, including high wire artists, tumblers, trapeze artists, jugglers, clowns, and animal trainers. These people spend their entire lives honing their skills.

In that era there was another significant difference between circuses and carnivals. Carnivals were, at that time, sometimes sleazy, containing acts like striptease shows. They also contained games of chance that were not always honest — rings in the ring toss that were too small to go over the good prizes, roulette wheels that were rigged to stop where the operator wanted. The circus, on the other hand, was innocent, wholesome good fun.

My parents were delighted by the offer to headline Pollack Brothers Circus and proudly accepted. Preparations began for their trek to California. I must admit, after all those years of dreams of the fun we’d have when we joined the circus, it broke my heart to see them set out without me. But by now I was married and had just given birth to my daughter.

Mom, Dad, Bobby, and Rick were on their way to their next great adventure. Mom pulled a house trailer behind the Packard. Dad drove a truck loaded with the globe and motorbikes, behind which was towed the globe’s base mounted on wheels.

To get to where the circus opened in California, Mom and Dad had to drive across the United States, including over the mountains in California. Mom found that to be a daunting experience. Although they intended to drive in a convoy, road conditions and those old vehicles pulling such heavy loads precluded that, so Mom insisted that Bobby, by then seventeen years old, ride with her. More than once she gladly let Bobby take the wheel to spell her off. Later she told me that she had been absolutely terrified pulling the house trailer through the mountains. Several times she had to take a run at an incline to get underway, and she trembled as she drove through winding mountain roads edged by sheer drops.

In the meantime, Dad was having his own troubles getting through the mountains with his old five-ton truck and heavy load. The engine in the truck sputtered to a stop on several occasions. It took all of Dad’s ingenuity to keep it going to their destination.

When they neared Oakland, California, where they were to first appear, they were met by a squadron of motorcycle police. They were so late that Pollack Brothers Circus had arranged for a police escort. With sirens blazing, lights flashing, and the roar of heavy-duty motorcycle engines engulfing them, they sped through the city, straight to the circus grounds, making an entrance worthy of their star status.

Mom told me that although she truly hated the harrowing drive to California and the trek between cities, she revelled in circus life. She easily made friends with other performers and enjoyed many good times with them. But it was a different story for Dad. He had no interest in developing friendships, and he soon tired of the laborious grind of setting up the Globe of Death, doing the shows, tearing down, then driving to the next spot. On the carnival show train he could rest as the train wound its way to the next town. With the circus there was no respite. At the end of their contract, they sent the Globe of Death into retirement.

Circus life must have been fantastic in the days when performers and equipment travelled together on long show trains, but my parents were a few years too late for that. The Globe was a monster to move. Lugging their own equipment around from city to city in their own vehicles took all the romance from it.

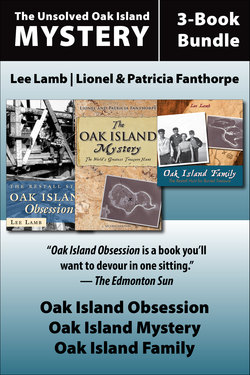

And it was at this moment that Oak Island came into their lives.