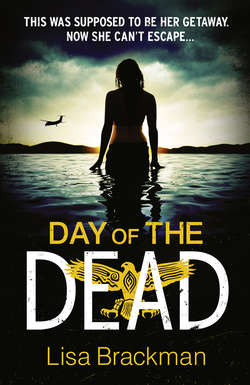

Читать книгу Day of the Dead - Lisa Brackman - Страница 8

CHAPTER FOUR

Оглавление‘I think you will want to take a cab,’ the woman at the front desk told her after looking at the address written on Gary’s card. ‘It is a ways from here, and up the hill.’

‘But close enough to walk?’

‘If you like walking.’

Between last night’s drinks and the margarita she’d just had at lunch, she could use the walk. ‘I do.’

‘Maybe two miles.’

I could take some pictures, she thought. Like she’d set out to do yesterday, before Daniel’s phone rang.

She went back to her room, grabbed the Che bag with Daniel’s clothes, retrieved her Olympus E-3 from the hotel safe, and set off, heading south from the hotel, up a road that curved around the hill.

The heat made it hard to keep walking. It felt like being smothered in a steaming-hot blanket. Sweat dripped into her eyes, smeared her sunglasses when she pushed them onto her head. And trying to take pictures while juggling her purse and the Che bag was awkward. The camera, which usually fit so comfortably in her hand, slipped in her grip.

Nothing was going to go right today.

She tried. Shot a few images. Nothing very interesting. Wrought iron and bougainvillea. Superhero piñatas. She’d seen these photos before, she was certain, and seen them better executed.

Michelle put the camera back in its bag and slung it over her shoulder.

The road ahead was cobblestoned, the banks lining it tangled with browning vegetation that would not green until after the summer rains, with plastic bags and food wrappers caught up in the branches. A lot of the houses looked expensive. New construction clung tenuously to the hillside, as though the flesh of the land had wasted away, leaving skeletal frames stacked unsteadily on top of one another, foundations undermined before they’d even been laid. With enough rain saturating the hill, she could just see one of these buildings giving up, letting go, the cheap rebar popping out of the ground like a rotten tooth.

Halfway up the hill was a little street that branched off the main road at an impossibly steep angle. She followed it, per Gary’s directions. The street led to a cluster of small, multistory buildings – apartments or condominiums.

The one on the right, Gary’s note said, light brown with a dark roof.

She looked. She thought the description fit, but blue tarps covered most of the roof, and there was other evidence of ongoing construction or repairs: a small cement mixer and a pile of gravel, a dug-up walkway, a boarded window. No workers. The place looked abandoned.

Daniel’s unit was the one on the upper right, according to Gary’s note. The tarps extended halfway across what would have been his roof.

Michelle stood there for a moment. She was absurdly sweaty, drenched; her blouse was actually wet, her hair separated into salty tendrils. Really, she wasn’t in any condition to see Daniel if he was there.

Did she want to see him? She wasn’t sure.

Stupid, she told herself. You need your phone. You’ve come all this way. Say hello, how are you, and good-bye.

She shifted the tote bag on her shoulder and approached the building.

An external staircase with a wrought-iron banister led up to Daniel’s unit, crossing the side of the building and leading to a balcony facing the ocean, wide enough to accommodate two chairs and a small glass table.

When she reached the balcony, she could see only a sliver of water above the roof of the building below. Still a nice view, she supposed.

There was no name on the door, no number, no mailbox. She’d have to take Gary’s word that this was the right unit. If it wasn’t … well, this was a small building. Someone would have to know where Daniel lived.

If no one answers, she thought, I’ll leave the bag by the door with a note. Take his phone back to the hotel, and he can pick it up there.

Heart pounding, she knocked on the door.

Which swung open. About six inches before the rusting hinges slowed it to a halt.

Michelle hesitated at the threshold.

‘Daniel?’ she called out.

She heard something from within. Not a person. She couldn’t make it out at first. A sort of hum.

A fly flew out the door, bumping into her shoulder.

I have to look, she told herself. I have to look.

She pushed the door further open.

It was dim inside, the curtains drawn, and hot. The smell, the flies – for that was the hum she’d heard, the buzzing of flies – hit her at once, and she couldn’t entirely sort out one thing from the other – the darkness, the closed heat, the smell: a sweetish rot. She fumbled for a light switch, thinking there must be one, but there wasn’t, not by the door at least.

Her eyes adjusted. It wasn’t really dark. There was enough light seeping through the curtains, from the open door.

The living room. This was the living room. It was simple, hardly anything in it. A couch. A chair. A television. A coffee table.

On the coffee table was something dark, an oval shape with protrusions she couldn’t make out. The thing almost seemed to shimmer, as though its lines were mutable, fluid, shifting ever so slightly.

She approached the table, and a cloud of flies rose from the object.

A head.

She shrieked, batting away the flies, one of them hitting her lip, another, her eyelid, her ear. She thought she might have inhaled them, and she swatted at them and retched a little, then finally stood still. She looked again.

It was a pig’s head. A pig’s head, sitting on the coffee table. On top of a Time magazine, next to an empty beer bottle. Covered with flies. Maggots, too, little white filaments that pulsed and contracted as they burrowed into the rotting flesh.

For a moment she could only stand there. She felt nothing at first. How was one supposed to regard this? It didn’t make sense.

Something prickled the skin of her forearm. She looked down.

A fly, rubbing its legs together.

Get out, she thought. Just get out.

She took a few steps back, toward the door, toward air and light, stumbling a bit, the back of her hand striking the doorknob. She clutched at it to steady herself. Leaned there against the wall, hand on doorknob, until her heart slowed and she could think again.

What did it mean? Why would someone do this?

Maybe she should call the police. She wondered how you did that here. Was it 911? Or something else?

But what would she tell them? That she’d found a pig’s head in an empty apartment?

There was no one in the apartment. She was certain. How could you stand to be in there with a rotting carcass on the table? There was no movement, no sound other than the flies.

Then she thought maybe there was someone, unconscious or dead.

Don’t be stupid, she told herself, but the idea burrowed itself into her head, and she had to be sure.

The apartment had a kitchenette, separated from the living room by a bar counter, and a short hall with three doors opening off it. A bathroom – blue tiles, plastic shower curtain. A toothbrush, some toothpaste, and a few sundries. Nothing much. Some curly dark hair in the sink.

The door next to that opened onto an odd little room – a bonus room, she supposed you’d call it – with a small barred window high up a whitewashed wall. You could put a daybed in here if you had guests, Michelle thought, but there was no furniture, just a workout bench, some barbells, a bag of golf clubs, and what looked like snorkeling equipment in a couple of crates beneath the window.

On the other side of the hall was the main bedroom.

No body on the bed. Michelle almost laughed. Of course there wouldn’t be. The bed was big, a king. Well, Daniel probably had his share of overnight guests, judging from her encounter with him – though anyone who didn’t know her well could say the same of her based on that night, and that wasn’t how she was, not how she’d been for a long time, anyway.

Don’t be so quick to judge, she told herself.

But it was hard not to wonder. The apartment – the condominium – was modest. Anonymous, almost. No paintings on the walls. Hardly any books. Nothing personal at all. Not much different from her room at the hotel.

This must just be a vacation home for Daniel, Michelle thought. Not the place where he actually lived.

Back in the living room, the flies had regrouped on the pig head.

Just leave, she told herself. It’s not your problem, and you have a plane to catch tomorrow.

But if it was something criminal … People knew she planned to come here. Gary knew, and Vicky and Charlie. If she just left, would that implicate her somehow?

She felt the camera tucked against her side as the thought occurred to her.

I should take pictures.

Just to document it. She could decide later whether she needed to show the photos to anyone. But at least she’d have proof of what she saw. Just in case there were any questions.

She hadn’t intended to get artsy, only snap off a few clear shots, but as she focused on the pig’s snout, a part of her noted that it was a compelling image, with the flies around its eye sockets, the beer bottle next to it, the television in the background. As bland as the room was, the pig’s head was the only thing that really drew your eye.

Still Life with Pig Head and Beer Bottle, Michelle thought, adjusting the depth of field, taking another shot, then the angle, shooting again. She almost laughed. All this time in Puerto Vallarta, and she’d finally found a good picture.

‘What … ?’

She dropped the camera against her chest.

‘What the fuck?’

Daniel stood there in the doorway.

‘I …’

In two strides he’d crossed to the coffee table. ‘What the fuck is this?’

His fingers dug into her arm, just beneath her bicep. ‘You … Who told you to do this?’

‘What are you talking about?’

She stared at his face: rigid and white with anger.

‘I have some of your things,’ she said. ‘I just came here and saw this. I thought …’

‘Who told you where I live?’

‘Gary,’ she said. ‘Please let go of me.’

‘Gary?’ He released her arm with a jerk. ‘How do you know Gary?’

‘I met him at the Tiburón,’ Michelle said. ‘I didn’t know how to get a hold of you. Gary gave me your address.’

‘Why didn’t you just call?’ The anger had not diminished, only retreated.

‘I have your phone.’ She started to reach into her purse, and instantly he tensed again, not with anger this time but something cold and predatory.

She froze. God, did he think she had a gun?

‘Check yours,’ she said. ‘I think it’s mine.’

He reached into the pocket of his cargo shorts and pulled out an iPhone. Black. He powered it up. ‘Shit,’ he said after a moment. ‘It … it was off. I just left it that way.’

‘For two days?’

‘I wanted to get some rest and not have people fucking calling me.’

‘So can we trade phones now?’ She felt a rush of anger. ‘You’re not going to … to attack me?’

‘Sorry. I’m …’ He lifted his hand to his forehead, winced. His head was shaved where he’d been cut, a patch between crown and temple covered with a square of gauze. ‘Fucking Gary.’ He attempted a smile. ‘This is probably his idea of a joke.’

‘A joke?’ The buzzing of the flies, the smell of rot, the close, shut-in heat of the apartment made her suddenly dizzy. ‘I need some air.’

She pushed past Daniel and sat down on one of the chairs on the balcony, let her head fall into her hands.

‘You okay?’

‘Fine.’ She raised her head. ‘What kind of joke is that?’

‘A stupid one.’ Daniel sat down in the chair next to her. ‘He knew I checked into a hotel for a few days. Air conditioner’s busted here, and I felt pretty lousy. Figured I’d let somebody bring me food and make my bed.’

There was something he wasn’t saying, something that didn’t fit, but Michelle couldn’t think of what it was.

‘You want a beer? I think there’s a couple cold ones in the fridge.’

He sounded friendly enough, but the way he looked at her, studying her face – was that concern or something else?

‘That’s okay. I think I’d better go.’

‘No, listen, stay a minute. You had a shock. Let me get you a beer.’

He got up before she could object.

By the time Daniel had returned with the beers, bottles already sweating in the heat, she’d figured it out. ‘Why me?’

‘Huh?’ Daniel handed her a bottle. Bohemia. She’d had that a few times in Los Angeles.

‘If he was playing a joke on you, why did he send me up here to find it?’

‘He’s an asshole.’

‘He doesn’t even know me.’

‘Guess he thought it would be funny,’ Daniel muttered.

The sun was striking the balcony now, the light glaring. He squinted for a moment and put on his sunglasses, which had been propped up on his head. Serengetis, she thought.

Michelle rested the beer on her cheek for a moment. The chill felt even better than drinking it.

‘So the pictures,’ Daniel said. He was smiling, trying to keep his voice friendly. ‘Why were you taking pictures of that thing?’

‘I thought there should be a record of it. In case someone threw it away.’

‘Are you a photographer or something?’

She shook her head. ‘It’s just a hobby.’

They sat in silence for a while. What else was there to say?

‘I should go,’ Michelle said. She reached into her purse and got out his phone. He retrieved hers from his pocket.

‘Let me get you a cab.’

‘You don’t need to.’

‘I want to.’ He smiled again. Maybe it was genuine this time. ‘Look, I’m really sorry about how I acted just now. It was just … kind of a shock, finding you and that in my place, and … I’m still a little jumpy over everything. You know?’

She supposed she did. ‘Don’t worry about it.’

He walked her through the apartment, past the pig’s head.

‘Let me buy you dinner,’ he said suddenly. ‘You went to a lot of trouble, and I didn’t exactly thank you for it.’

‘Thanks, but … I’m leaving tomorrow, and I need some time to pack.’

It was a lame excuse, and he had to know it, but he couldn’t really want to have dinner with her after everything that had happened, could he? It was probably just a belated courtesy on his part, and she wasn’t interested.

He was a nice-looking man, and maybe none of this was his fault, but she’d had enough. Enough of him, enough of his creepy friends and their sick jokes. Enough of this place.

It was time to go home.

‘Well, if you change your mind …’ He stared at her, eyes hidden by his sunglasses.

‘I have your number,’ she said.

She didn’t, but he didn’t need to know that.

He still looked pale, she thought. Behind him the pig’s head pulsed with flies. ‘Do you … need some help with that?’ she asked reluctantly.

‘Thanks. That’s … Thanks.’ He smiled again, a real one. ‘If you could, maybe just hold the bag?’

Daniel put on a pair of rubber gloves he had stashed under the kitchen sink, and Michelle held the garbage bag. He picked up the pig’s head, holding it as far away from his body as possible. Michelle did the same with the garbage bag.

Even after they twisted the bag shut, she could hear the buzzing of trapped flies.