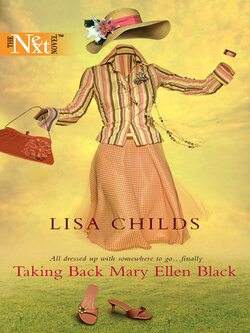

Читать книгу Taking Back Mary Ellen Black - Lisa Childs - Страница 9

CHAPTER D - DAY Divorce

ОглавлениеUsually, the A, B, Cs start it all, the beginning of the alphabet, of words, sounds, books. In this case, the first chapter of my life will start with D, for divorce, which, in some ways, is really when my life began—when I first took back Mary Ellen Black.

My husband, ex-husband as of today, hadn’t wanted her, hadn’t even bothered to turn up at the courthouse to contest my asking the judge for my name back, the name I’d been born with but couldn’t use again until I was told it was legal. Eddie hadn’t contested my full custody of the girls, either; he knew pushover Mary Ellen would let him see them whenever he wanted. But he hadn’t wanted, not since he’d walked out on us for the twenty-year-old waitress at the restaurant he owned—or barely owned. If what he’d convinced the Friend of the Court was true, the restaurant was losing so much money that he couldn’t pay child support.

And so I was stuck where I sat, in my grandmother’s car, in the alley behind my parents’ house in the old West Side Grand Rapids neighborhood where I’d grown up and where I’d had to return after the bank had foreclosed on my gorgeous six-year-old house in Cascade. The repo man had taken my SUV, so I had Grandma’s Bonneville to use since her cataracts prevented her from driving anymore. Of course, she could still keep track of ten bingo cards every Saturday morning at Saint Adalbert’s.

Sitting in the car behind my parents’ house wasn’t going to help me figure out how everything had gone so wrong. I knew that, but still I couldn’t summon the energy necessary to open the car door and crawl out. I’d done enough crawling when I’d begged Eddie to come back, to work things out, and then when I’d lost the house, I’d crawled home to Mom, Daddy and Grandma.

No, Mary Ellen Nowicki had done all the crawling; Mary Ellen Black was stronger than that. I didn’t know much else about her anymore, but I knew that. Yet still I slumped on the bench seat of Grandma’s old Bonneville. No wonder her blue-haired head didn’t show above the steering wheel. This seat was low, really low.

I glanced over the wheel and around the alley. No yard. Just the big, square two-story house where I’d grown up, the alley and the detached garage. Inside the dark shadows of the garage, the tip of a cigarette glowed. Dad had knocked off early from the butcher shop and was checking his oil. That’s what he told Mom he was doing when he was really out getting a smoke. Nobody checked his oil as often as Dad did.

If he wanted to talk to me, he would have stepped out. Despite living in the same house since the foreclosure on mine a few months ago, we’d managed pretty well to avoid each other. I was his little princess, and he had always sworn to protect me from all the bad things in the world. He couldn’t protect me from this. And that hurt him more than it did me. I had grown up; I was responsible for my own happiness or lack thereof.

I pushed away the fleeting thought of turning the key in the ignition and backing out of the alley. Three blocks farther down was a bar, a strip club now. I could get a drink there. The fact that I didn’t drink didn’t erase the temptation. Hell, maybe I could even get a job there. Divorce was the only successful diet I’d ever gone on. My clothes hung on me.

A glance in the rearview mirror revealed lank, brown hair and a washed-out face. Yeah, like I could get a job in a strip club. I probably wouldn’t make as much as I did waiting tables at the VFW, and the biggest tips the vets gave were quarters. That was the only job I’d been able to get since being out of the workforce so long, as a stay-at-home mom. Before dropping out of design school to marry Eddie, the only job I’d ever had was waiting tables. But the job at the VFW was only temporary while the regular waitress was healing from a broken hip.

With a heavy sigh, I threw open the creaky door. Dad couldn’t ignore that sound. Nothing moved in the garage but the glowing tip of the cigarette. “Daddy?”

He eased out of the shadows toward the gravel driveway. “Mary Ellen?” He never lifted his gaze from the tip of his contraband.

“Yeah, Dad.” It’s me. Look at me! But we weren’t that kind of family. We didn’t face our problems. We ignored them until they walked out on us. We both turned our heads, scanning the alley and the little ribbon of grass between the garage and the house. “So, Mom’s gone?” I asked.

“Yeah, she took the girls and her mother to the store. Thought you might want to be alone after…”

But I wasn’t alone, not if he would look at me and talk to me, really talk to me. But that wasn’t happening. And Mom, fearing that I might fall apart in front of my children, had taken them away. I wasn’t allowed to fall apart with anyone. I had to do it in private, crying into the lumpy mattress of the foldout bed of the couch in the den. Maybe I didn’t want to wait until I was alone in the dark to fall apart. Not that I wanted to fall apart. “That was nice of her,” I said.

He nodded. “Yeah, your mother’s really worried about you. So are the girls.”

They’d had to leave their home and their school. Next week they’d start at a new school where they knew only a handful of neighborhood kids they’d met over the summer. Their world had fallen apart, and they were scared that I couldn’t fix it. They weren’t the only ones.

“I’ll be fine, Daddy.” Maybe if I repeated the lie enough, I’d believe it, like I had believed Eddie and I had had the perfect marriage, the perfect life…until debt and infidelity had eaten it away.

“Yeah, you’ve always been a smart girl, Mary Ellen. A real smart girl.”

The laugh slipped out. Daddy was the only one who ever complimented me, but he didn’t have a clue. “Thanks, Dad.”

“I mean it, Mary.” I detected a slight slur and eased closer to him. Beer breath almost covered the scent of blood and garlic that clung to his clothes. So he still had another stash from Mom; I’d thought he’d given up drinking years ago. With his high blood pressure and his high cholesterol, cigarettes and alcohol weren’t just forbidden, they were suicidal. If only I’d had an ounce of my father’s strong, stubborn will…

“Got another one, Dad?”

“Smoke?”

Since my eyes were already tearing up, I doubt I could adopt that vice of his. And I’d die if my girls ever saw me smoking. “A beer.”

“You don’t drink.”

“I just started.”

He hesitated a moment before easing into the shadows of the garage. His beefy hand wrenched open the rusty door of an old refrigerator, and he snagged the last two cans clinging to the plastic rings of a six-pack. “You sure?”

I wasn’t sure about anything. “Is it cold?”

“Damn thing may be old, but this fridge could freeze a man’s—” His round face flushed. “Let’s just say it’s got a lot in common with your grandmother.”

Another laugh slipped out. Grandma Czerwinski was only cold to Daddy. She had never believed he was good enough for her daughter, her precious only child. And Daddy had been a hell-raiser in his day.

The cold can shocked me back to the important issues. I popped the top, breaking a nail. Icy foam fizzed over the rim and across my fingers. I slurped at it, ignoring the sour taste. How low had I sunk if I had to get drunk with my dad? Lower than the bench seat in Grandma’s old Bonneville.

Not an especially outgoing person, I’d only had one really good friend and a few friendly acquaintances when I’d married Eddie eleven years ago. The friend had hated Eddie and vice versa. And then I’d become too busy for the acquaintances and lost touch. I’d been a wife and mother, throwing myself into doing the roles until I performed them to perfection.

“So, did Morty the lawyer get you the money?” Dad asked after we’d slurped some more of our slushy beers.

Another laugh bubbled out, this one edging toward hysteria. “Money? What money?”

“The money, Mary. The child support and mortgage money that jerk owes you!” Getting Daddy worked up was never a good idea. Too much of the scrapper remained despite his gray hair and potbelly.

“There is no money, Daddy, nothing but a mountain of debt. Besides the house and the car, he’s on the verge of losing the restaurant, too.” And that would upset Eddie far more than losing me. He’d had to know his dreams were crashing down around him. Why not turn to his wife instead of some girl?

Dad slammed his fist down on the hood of his pickup truck, which he’d backed into the garage. “Son of a bitch!”

“Daddy—”

“I’ll get you some money, Mary Ellen. We’ll get your house back.”

I shook my head. “I can’t afford it. Not the taxes, not the utilities. It’s too much for me.”

“We got some money saved, your mother and I. I can borrow against this place. We’ll help you!”

I smiled over the oft-repeated offer. I knew he meant it; that he’d mortgage away his life in a minute if he thought he could get mine back for me. But he couldn’t. The house didn’t matter anymore. Sure, losing it hurt, but I’d grabbed a few more things, what I could fit in the trunk of Grandma’s car, and a Volkswagen would fit in that trunk. I had a twinge in my back from getting in an antique chest and a couple of oak end tables. I’d left the wedding portrait hanging on the wall, and the answering machine on the gleaming granite counter, the tape full of threats from creditors for Eddie to pay up.

I gulped a mouthful of frosty foam. “I’m better off without Eddie.” I’d been saying it for the last six months, but I think this was the first time I believed it, that I knew it. I would be better off without the lying, cheating snake. The man who’d left me for the twenty-year-old was not the man I’d married. Something or someone, maybe even me, had changed him over the years.

“I’m sorry, Mary Ellen.” The anger had left Daddy, and he sagged against the truck. His broad shoulders slumped, and his head bowed. “I shouldn’t have made the marriage happen…”

“I could have said no, Daddy. I could have raised Amber alone. I know Mom and Grandma and you were worried about what people would think, about the neighbors…” I glanced toward Mrs. Wieczorek’s house where curtains swished at a back window overlooking the alley.

“You think I care what people think?” He laughed. “I leave your mother and grandma to that craziness. I wanted you to be happy. I wanted you to have what you wanted. I thought you wanted Eddie.”

So had I. I’d loved the man he’d been then. “What are you saying, Daddy?”

“He told you. I’m sure he told you. A man like him—he’d like throwing it in your face—”

My stomach pitched more with dread than from the beer. “What?”

“I threatened him. I told him I was going to grind him up for hamburger, if he didn’t marry you.”

A shiver rippled down my spine. “You threatened Eddie into marrying me?”

Daddy glanced up, meeting my eyes for the first time. “He didn’t tell you?”

“No.” Now it made sense that Eddie hadn’t been able to look at raw hamburger without gagging and why he’d never gone to Daddy’s butcher shop. “But when he left, he said he’d never loved me. That’s probably the only time he told me the truth.” Because he certainly hadn’t told me about the growing debt. I set down the beer can on the hood of the pickup truck.

“I’m sorry, Mary. I never meant to hurt you…”

I flung my arms around my father’s protruding stomach, hugging him close. “You were just trying to get me what you thought I wanted, Daddy. And I did love him then.” As much as I’d like to, I couldn’t lie about that.

He patted my head. “I’ll make this right, Mary Ellen. I can get you the money you need.”

I imagined him, wearing his bloodiest apron and waving a meat cleaver, storming into Eddie’s restaurant. Though I enjoyed the look I imagined on Eddie’s face, I couldn’t risk Daddy winding up in jail for a little payback. “No, Daddy, it’s time I figure out what I want now and get it for myself.”

A small smile played across his broad face. I’d like to think it was pride, but I knew it was pity. He didn’t think I could do it—either figure out what I wanted or get it if I did happen to figure it out. But Daddy was the only one who ever complimented me, so I waited for some words of encouragement. And I waited while he swilled down the rest of his beer and then the rest of the one I’d left on the hood of his truck.

When the engine of a car rumbled in the alley, he still hadn’t said anything. He just passed me a piece of jerky from a bag he carried in his pocket. “Your mother’s back. Eat this, Mary, it covers up anything.”

I bit into the spicy, dried meat. Garlic and cayenne pepper exploded on my tongue, warming it. No wonder Daddy always smelled like garlic.

Mom’s minivan crunched over the gravel driveway as she pulled it next to Grandma’s Bonneville. The side door slid open, and my six-year-old Shelby, vaulted out, blond pigtails flying. “Mommy!”

I caught the little bundle of energy in my arms and pulled her tight. “Hi, baby. Did you have fun with your grandmas?”

She nodded. “We got Happy Meals. Grandma Mary likes the nuggets.”

I looked over Shelby’s head and into the interior of the van. Ten-and-a-half-year-old Amber sat in the back seat, hunched over a book, her glasses slipping to the end of her little nose. My oldest was always buried in a book. Better, I thought than the sand where I’d had my head buried lately.

“Did you eat yet?” my mother asked as she slid out from behind the wheel. My mother’s cure for every ailment: feed it. Her expanding waistline proved she took her own advice. But I couldn’t eat her greasy cooking or listen to her well-meaning advice. She’d been doling out a lot of both since I’d come home, the way she had the first nineteen years of my life. She leaned close to me and sniffed. “Oh, you got into the jerky with your father.”

That wasn’t all I’d gotten into with Dad. More than the beer and the secondhand smoke, I’d gotten perspective. I was better off without Eddie, and I could take care of my daughters and myself. I wouldn’t be trapped in this house another nineteen years.