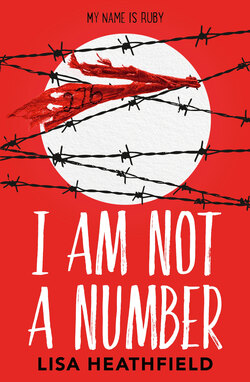

Читать книгу I Am Not a Number - Lisa Heathfield - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO

Оглавление‘Enough of the swarms of people entering our country. We will close our doors against the scum of the world, those who suck our country dry.’ – John Andrews, leader of the Traditional Party

‘You’re not coming and that’s final.’ Darren’s talking with his mouth full, which Mum always tells us not to.

‘You’re not my dad,’ I say quietly, but loud enough for him to hear.

‘No, but he’s your stepdad, so that’s the next best thing,’ Mum says. ‘Besides, we need you to stay home to look after Lilli.’

‘But I want to come.’ Tonight’s demonstration is apparently going to be the biggest local one yet. The armbands they gave out earlier have unsettled the Core supporters and people want to protest before the Trads have a chance to make the rest of the country wear them.

‘Well, you can’t.’ Darren has finished his meal in about one second. I don’t think he means to slam his fork down quite as hard as he does. ‘Nothing is worth putting you girls at risk.’

Lilli might lap up this violin talk from him, but it doesn’t work with me.

‘Then how come it’s okay for Mum to go with you?’ I ask.

‘Because we’ll be fine,’ Mum says. ‘And it’s better than us sitting back and doing nothing. We have to stand up to them before things go too far.’

‘Dad would let me go,’ I say, but even though he’s a hardline Core supporter I’m not sure he would.

‘Well your dad’s not here,’ Mum says, taking my sharp words and throwing them back so they hurt me instead. ‘And if he chooses to live hundreds of miles away then he loses the right to make day-to-day decisions.’

Darren stands up. He’s usually the one who makes us all wait until everyone’s finished eating. Even on those nights when he wants to rush off to the gym.

‘Will the protest make a difference?’ Lilli asks. She looks so young. When I was twelve all I had to worry about was whether my hair was the right length.

‘We’ve got to try something to make them listen,’ Mum says. But she must know that even if we all had megaphones and shouted from the tallest hill, the Trad’s ears are so bunged up with their prejudices and their egos that they’ll never hear us.

‘Don’t answer the door to anyone,’ Mum says. She’s all wrapped up for winter, even though it’s only September. Maybe she feels protected underneath her coat and scarf.

‘Just stay inside and watch a film together,’ Darren says, putting his hand on my arm. He’s frightened, I can tell. Underneath a weird energy that’s fizzing off him there’s something deeper that he’s trying to hide.

‘Will it be dangerous?’ Lilli asks.

‘Of course not,’ Mum says. ‘It’s just a peaceful protest to get our voices heard.’

‘You said it might be a risk,’ I say to Darren.

‘We’d just prefer you to stay here and look after Lilli,’ he tells me.

‘I don’t think they’ll be expecting so many of us,’ Mum laughs, as if she’s just going to a party or something.

‘They’ve got guns, Mum,’ I say and her smile disappears.

‘They only have them to scare us. They won’t use them, Ruby,’ Darren says.

‘How do you know?’ Suddenly I don’t want my mum to go. I don’t even want Darren to go.

‘They’ve got messed up ideas,’ Mum says, ‘but they’re not murderers.’

‘Can’t you stay here?’ Lilli asks as Mum kisses her on the head.

‘We have to stand up for what’s right,’ she says.

‘Come on, Kelly, we’ve got to go,’ Darren says and he opens the front door.

‘I love you, Mum,’ I say, but I’m not sure she hears as she’s already walking down the path.

Darren hugs Lilli, but he knows not to try with me. ‘We won’t be long, but don’t stay up if it’s late.’ And he waves at us as he runs after Mum.

‘Right,’ I turn to Lilli, my voice too bright. ‘Popcorn and a movie?’ She looks at me as though she’s waiting for the walls around us to crumble into dust. ‘They’ll be fine, Lils,’ I tell her over my shoulder as I walk into the kitchen. ‘They’ll be back before we know it.’

I get a message from Luke as soon as I open the cupboard.

Dad and I are going to the protest.

I’m not that surprised. His dad’s taken him on protest marches since before he could walk. But it makes me feel even more annoyed that Darren won’t let me go.

See you there, I text back before I even think about it.

You’re coming?

Yes. I’ll look out for you.

I close the cupboard and go into the sitting room. Lilli is already curled up on the sofa.

‘Change of plans,’ I say as casually as I can.

She looks up from her phone.

‘You don’t want to watch a film?’ she asks.

‘We’re going to the protest.’

‘We can’t.’

‘Of course we can. Our voice is important too.’

‘But Mum and Darren said we couldn’t.’

‘We’ll only go for a bit. If we’re back before them they won’t even know we were there.’

‘I could stay here on my own,’ Lilli suggests.

‘You know you can’t. It’s too late.’

‘Peggy’s next door. If anything happens I can call her.’

‘She’s like a hundred and fifty years old,’ I say. ‘She’s not going to be much good if you pour boiling water down yourself. Or flood the house or something.’

‘That’s stupid.’

‘It’s not. It could happen.’ I put out my hand to pull her up, but she stays sitting. ‘Please, Lils. I really want to go.’

‘What if the soldiers are there?’

‘They probably don’t even know it’s happening. But even if they are there, Mum says they won’t actually do anything.’ I walk into the hallway and hope she’ll follow. ‘Luke’s going to be there.’

Lilli appears within a second. I think she might love him almost as much as I do. ‘Is he allowed to go?’

‘He’s going with his dad.’

‘Will we see him?’

‘Hopefully.’

‘Okay,’ she says and already she’s looking for her shoes as I put on my coat. I try to ignore the doubt that’s pulling at me as she sits on the bottom stair to tie her laces.

‘Mum’ll kill you if she finds out you’ve taken me.’ Lilli’s spinning a bit from the excitement. This is a big deal for her as she never usually does anything she’s not meant to.

‘She’d kill me if I left you here.’

Lilli jumps up, grabs her coat and hooks her arm through mine. ‘Then you’re dead either way, aren’t you?’

As soon as we’re outside, I know it’s not a good idea. Our street seems strangely silent. One car drives past then turns the corner at the end. The lamplights are on even though it’s not completely dark.

‘Are you warm enough?’ I ask Lilli and she nods.

Most houses’ curtains are closed, but Bob Whittard’s are open and he’s sitting in his armchair, so I wave to him when he looks up. He doesn’t wave back. He doesn’t even smile. It feels like a hard line is being drawn down between those who support the government and those who are against it. Surely it’s something we can scrub out now, before it gets too deep?

As we get closer to the park there are more people about. They’re mostly as silent as we are as they scurry along towards Hebe Hill. There are soldiers too when I told Lilli there probably wouldn’t be any. One is standing at the end of Shaw Street, two more along Beck Avenue.

I hold Lilli’s hand tight as we take a shortcut through the alley. It’s darker in here and has a strange quiet, as though a lid has been put on the world. Ahead, there’s the entrance to the park and there are so many people, but I don’t know if seeing them all makes me feel safer, or more scared. I don’t recognise anyone, but the determination on their faces is all the same.

‘Have you texted Luke?’ Lilli asks.

‘I will when we’re in there.’ Although I’m not sure now how easy it’s going to be to find him.

We go through the park’s gate and have to follow everyone along the path. The flower beds either side are still filled with delphiniums, the first flowers Dad taught me to name. Seeing them makes me miss him, so I text to tell him that we’re here to protest against the Trads. I think he’ll be proud, but I know I won’t get a message back soon. I’ve learned the hard way not to wait for a reply.

From where we are we can see people covering the top of the hill. Someone is holding a megaphone, but their words aren’t clear enough yet. I feel better now that we’re here. I’m excited more than scared and I think Lilli is too, judging by her wide eyes and smile as she looks around.

‘Can you see Mum anywhere?’ I ask.

‘Shall we hide if we do?’

‘Perhaps.’ I know Mum would be angry, but maybe she’d be a little bit pleased that we’re protesting too.

There’s a crowd in front and behind us. I didn’t know there were so many Core supporters in our town. They’ve probably travelled in from a bit further away, but I’m surprised so many people want to show it. I wonder if some of them have come over to our side since the election? Since the government’s ideas have got crazier and crazier. I can’t imagine that everyone who voted for the Trads will be happy with restricted internet use and having their relationships monitored.

It’s almost single file again as we curve around the edge of the playground. I used to spend hours here, being pushed on the swing by Mum and Dad, then me pushing Lilli, then friends pushing each other and being told to leave. There’s no one there now. The swings aren’t moving, there are no shadows on the slide. Tomorrow there’ll be children laughing again, but for now we walk past with hardly a word.

There’s more space around us when we get to the hill. Hebe bushes are planted in random clumps for us to walk around. Their colour matches the purple of the Core symbol, so it seems that nature is on our side too. I reach out to touch the flowers. They look a bit like thistles, but they feel like feathers. If it was daytime there’d be tons of bees on them.

‘There are lots of people here,’ Lilli says, looking up at me.

‘How very perceptive of you, Chicken Bones,’ I say and she thumps me.

Three men are at the top and they must be standing on some sort of stage. They stick out above everyone. Two of them hold the purple Core Party flag, with its yellow steps going up the middle. The other has the loudspeaker and now we can hear his words. They rumble through the crowd in front of us and light a fire round my bones.

‘We won’t be forced into silence!’ the man shouts. ‘We won’t be ruled by bigots who love only to hate.’ The people around us are even louder now and I start to cheer with them. ‘We will champion your rights because each and every one of you has a right to free speech, a right to freedom of movement. A right to freedom!’

I’m glad we came here. It’s good to feel a part of this, to feel we might finally make a difference. That things really might change.

‘Our rights should be at the core of our society.’ His words thunder from him as people cheer again.

I look up into the sky. It’s a clear night and stars are beginning to reach out. Thousands and thousands of them watching, looking back at us. It makes me feel part of something even bigger.

‘We want to live in a tolerant country!’ The man’s words jump among us, landing on our hands, our ears, our skin. They skim up to the leaves and I imagine the wind picking them up and taking them to whisper in strangers’ ears. To let them see. Let them believe too. ‘A country that does not judge. Does not turn away those who cry for our help. We champion the rights of everyone, regardless of your class, your faith, your sexuality, your roots.’ The roar from the crowd is thick enough to touch. My arm stays in the air like everyone else’s. ‘It’s not a solution to cut down those who cry for help. Instead, we will listen. We will care. And we will rebuild our society from the foundation up. We won’t cease in our fight to champion the rights for everyone.’

‘Champions! Champions!’ My voice joins in with the chant, but Lilli stays silent, her arms by her side.

We’re getting pushed forwards. More people must be coming from the back.

‘Core Party for peace!’ the man with the loudspeaker calls above us all.

Suddenly we’re pushed so far forward that Lilli stumbles and I only just manage to pull her upright again. The crush is instant and people start to scream.

‘It’s okay,’ I tell Lilli. ‘They’ll make space.’ But it’s getting difficult to speak.

People scramble on to the stage and the man with the megaphone falls and disappears. And I see now, through gaps in the shoulders, that there are soldiers with plastic shields and they’re driving themselves into the protesters, forcing us together.

‘I can’t breathe,’ Lilli says, as more bodies press into us.

There’s yelling and it seems so distant as I lose my grip on Lilli’s hand. Everyone is pushing us, pushing everywhere, trying to run, but there’s nowhere to move. We’re all stuck and more people keep pounding into us and there’s nowhere for us to go.

My breath is being squeezed from me.

‘Get back,’ someone shouts. A woman beside me falls and I try to reach for her, but she’s sucked under and trampled on.

‘Lilli,’ I say, but the word is only a pinch of letters.

Mum. Luke.

My sister has tears in her eyes, but I can’t hear her crying.

We’re heaved forwards, my feet barely on the ground. My lungs are being crushed and there’s not enough air.

I see Lilli lifted, pulled up. A man grabbing her with one arm, pushing her over the heads of others.

‘Ruby!’ she screams, but I can’t see her. My eyes hurt. How can there be so much air above us, just out of reach?

We move forwards. I trip over something soft, but the pressure of the bodies around me keeps me upright. People are shouting, desperate. Get back. Make space.

We move as a dying animal, down the side of the playground as people pile over the fence, stumbling and falling. There’s screaming as we spill forwards until there’s space, enough air now.

‘Lilli.’ My voice is too quiet. Yet my breathing is easier, just splinters in my lungs now. ‘Lilli!’ I don’t want to be crying, but everywhere there are people shouting and none of them are my sister. The man lifted her up and she’s gone.

I’m being pushed further along and I look up as a soldier raises his baton and he brings it down on a man. I hear him hit him, a deadening thump on bones and I know I have to get away from here. But I can’t get through, because people are fighting back, charging into the soldiers. I’m stumbling over crushed banners and there’s nowhere to hide. And everywhere there are the distorted faces of the soldiers behind their transparent shields. Just their eyes through their helmets and they raise batons and they strike out and I’m too close as panic burns my chest.

Someone in front of me falls, clutching his eyes. A soldier has a spray and I see him grab a woman by her coat and she begs as he holds the can close to her skin. And so I run. Past stumbling bodies, through a cloud of terror, wading through cries I’ve never heard. I’m at the fence with others and we’re clambering over it, someone helping me so I don’t fall.

I make it to the alleyway, but I’ve left my sister behind and my phone is ringing and it’s my hands that take it from my pocket and my mum’s voice is shouting and I tell her that I don’t know where Lilli is. Terror seeps from me into the wall at my back.

‘Lilli’s here,’ I hear my mum say.

She’s at home.

I run, the phone in my hand, through the streets I thought I knew, past houses with doors closed to me. I see someone running towards me and I know it’s Darren and he reaches me and hugs me so tight.

‘You’re safe,’ he says and I don’t know whether it’s my lungs, my heart, or my head that hurts as he pulls me towards our home. Where my mum is standing in the doorway and she holds me before I’m even inside and when our front door shuts behind us the relief to be safe is bright.

‘Jesus, Ruby,’ Darren is shouting.

‘You said the protest would be okay.’ I can’t make sense of the words I want to say.

‘I never said that.’

‘This isn’t helping,’ Mum says. ‘They’re back now.’

‘Where’s Lilli?’ I ask.

‘In the sitting room,’ Mum tells me.

‘She thought she was going to die, Ruby,’ Darren says.

‘But they’re both safe,’ Mum glares at him. ‘That’s the most important thing.’

‘We could have lost them.’ Darren’s voice is still too loud. ‘You saw it there, Kelly. You saw what those Trads did. They took a peaceful protest and they turned it into a deathtrap.’

‘I’m not going to have this discussion now.’ Mum goes into the sitting room and I’m left with Darren in front of me, his anger sharp.

‘The soldiers were hitting people,’ I tell him. ‘But we hadn’t done anything wrong.’ He steps forward to hug me, but I won’t let him. Sirens call in the distance. ‘Why did they do it?’

‘I don’t know,’ is all he answers.