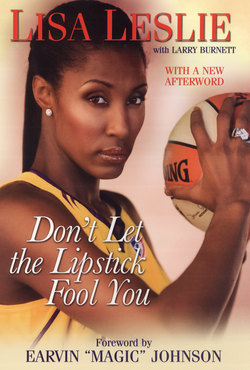

Читать книгу Don't Let The Lipstick Fool You: - Lisa Leslie - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2 How’s the Weather Up There?

ОглавлениеIt took a little work to get settled at Aunt J.C.’s house. She was divorced from my Uncle Craig and lived with her two children, Craig II, whom we all called Craigie, and Braquel. Craigie was my only male cousin. He was eighteen, loved sports, and was creative, smart, and cool. Braquel was fifteen. She was my hero. This girl would not back down from anything or anybody. She was so brave, smart, pretty, and athletic, too. She and Craigie had it made. Aunt J.C. always provided them with the best of everything. They had Barbies, dollhouses, trains, model cars, and very expensive clothes. My cousins had so many things that Tiffany and I did not. I figured they had to be the happiest kids in the world. Oh, they were happy all right, but once we moved in with Craigie and Braquel, I found them to be unaware of just how truly blessed they were.

My cousins did not get along at all. They would really fight. I mean fight with a capital OUCH! I never saw a boy and a girl battle the way they did. He would get on her nerves, and she would kick him. He would choke her. I never knew what to do, except to get Tiffany out of the way while those two went at it. Craigie would punch Braquel. She would punch him right back. They fought like grown men would fight. It was like I had the family edition of professional wrestling going on right before my eyes, but these conflicts were real.

When Aunt J.C. caught her kids in hand-to-hand combat, she would run in, kick off her heels, and jump on Craigie’s back. If that did not break things up, she would run to the kitchen, grab a skillet, and threaten to hit him over the head with it. No kidding! It was serious. Their brawls only happened every few months, but that was more than enough for me. I hated it when my cousins fought. I cried every time. When each free-for-all finally ended, Craigie and Braquel would get a whuppin’. That scared me, too. I knew I had not done anything wrong, but I still worried that I might be next in the whuppin’ line. It would not have been the first time I got spanked for something I did not do.

Aunt J.C. had punished me before, so I was overly nervous at her place. I really felt the pressure of trying not to be a bother in a house that was not my own. I made sure that Tiffany and I did not get in the way or ruffle any feathers. We tried to use as little hot water as possible to make sure that everybody had enough, and we always kept the noise to a minimum. Tiffany and I would put out a blanket (we called it a pallet) and sleep on the floor in the living room, where there was soft carpet under us. Aunt J.C. loved Tiffany and me as if we were her own, but I still felt like we were in the way. I knew Tiffany and I were loved, but I also knew it was uncommon for people to take two kids into their home, even if they were related. One thing I can say about my mom and her sisters is that they truly believe that it takes a village to raise a child. They were always there for one another, and since my village was made up mostly of women, I had a ton of role models, Aunt J.C. chief among them.

Aunt J.C. was so glamorous and fun. In a good, interesting way, she was all the things that my mother was not. Mom was more well rounded, but she was not always glamorous. She was bigger and taller than her sister. Mom would pick and choose when she wanted to look really sexy, but she always looked like a lady. Aunt J.C., on the other hand, always seemed to be in Diana Ross mode. She had the big hair, shiny lipstick, and lots of sparkly, unique outfits that made fashion statements. Aunt J.C. always went to work wearing heels and looking sharp. To this day, I have never seen her in sneakers. She wears nylons, really pretty dresses, and blouses that are made of linen, silk, or satin. Her hair is always curled, very stylish, and, do not forget, big. Her jewelry is terribly expensive. Her perfume has a scent of class that lingers for hours. When my Aunt J.C. enters a room, people take notice. I wanted to be just like that.

But I was feeling anything but glamorous. I was an awkward, gangly twelve-year-old who stood out at six foot one. I was literally head and shoulders above everybody else. When I was at school or walking home, kids would tease me about my size. They would point and laugh and say, “Wow! You are so tall! You look like Olive Oyl.” They called me all kinds of names. Skinny Minnie. Bony. I would come home crushed! Mom would tell me to keep my head up high and understand that when people talked about me, they were only exposing their own insecurities. I tried to see it that way, but it was difficult.

Mom spoke from experience. She had been six foot three since she was nineteen years old, so she knew all about growing up tall. Plus, she wore really thick glasses as a child. Kids made fun of her and called her names, but she never let her height discourage her.

Besides fitting in at school, one of my main concerns was fitting into clothes. I did not understand that when I was growing so tall and so quickly, every pair of pants I wore would look as if they had shrunk. The cuffs would stop well above my ankles. It looked as if I had rolled them up to walk through a flood. Truth was, I constantly outgrew everything that I owned, and nothing ever fit right. Mom started shopping for me in the men’s department. I wanted to wear fashionable kids’ clothes like everybody else my age, but my days of fitting into children’s clothing were over, and it was painfully embarrassing. What twelve-year-old girl wants to dress like a man? Not me.

My feet were size 12, and I walked around wearing these leather shoes that Mom bought for me on a trip to Tijuana. I wore those shoes every day for a full year. Before long, there were holes in the bottoms of them. Rain would seep in, soak my feet, and stain the leather. One day I got on my knees and prayed, “God, when people look at my clothes, make it look like they fit right, even if they don’t. Can I please be able to get pants and jackets that are long enough?” Then I would add, “And please let people see me as beautiful.”

I prayed a lot growing up. My family was pretty religious, but Dionne in particular used to go to church every Sunday to enjoy the choir and congregate with other people. She always was a people person. When I asked if I could tag along, it was one of the few times that she agreed without getting irritated with me. Dionne and I would walk together to church each Sunday, just the two of us. This gesture is the one thing I will always be grateful to her for; I am not sure if she ever knew it, but Dionne helped bring me to Christ when I was just seven years old.

So I believed in the power of prayer from a very young age, and I have never doubted that God answers prayers. I know that He does not always answer my prayers exactly the way I ask, but He does answer me eventually. To this day, whenever I pray, I say, “May Your will be done,” because I understand that God sometimes has something else in mind for me, a different direction, a new focus, or a greater plan that is more important for me than clothes that fit or shoes without holes. But when I entered Whaley Junior High in Compton in 1984, that was exactly what I prayed for. Instead, God gave me basketball.

For years I had to put up with people saying, “You are so tall. Do you play basketball?” I got sick of hearing the question. Before I began junior high school, the game meant nothing to me. It was not even a tiny part of my life. We did not have any basketballs at my house, and I had never watched a game on television, so I had absolutely no understanding of the sport. I had seen some neighborhood kids shooting baskets down the street, but I never considered playing until junior high.

Sharon Hargrove was a very popular girl in school. We called her Shay. She came up to me and asked if I wanted to try out for the basketball team. I was hesitant. After all, I knew I was not tough or strong. My most athletic activities had been tetherball, kickball, and jumping rope. I was very good at double Dutch. Basketball, though, was something completely new and different. But I wanted to fit in, and when one of the most popular girls invited you to join her team, you had to give it some thought. I decided to give basketball a try.

For the first time ever, I was trying out for a team. You could say I was more than a little behind on the learning curve. Our coach split our squad into layup lines. He wanted the right-handed girls in one line and the left-handed girls in another. Of course, I wound up being the only player in the southpaw line. I remember him saying, “Just hit the ball off the top of the square on the backboard.” I did, but about all I could do was make a layup. We went through some drills, and I did okay, but I vowed that the next day I would be right-handed so I would not have to be in a line all by myself again.

That tiny insecurity and my desire to feel included forced me to learn how to use my right hand effectively. Over the years, I developed to the point where I could do almost everything I needed in basketball with either hand. That turned out to be a real plus for me throughout my hoop career.

Meanwhile, Mom was still trucking across America. I really wanted to make the Whaley Junior High team. I knew it would do a lot for my popularity, but I was nervous about the results. When the team was finally selected and I realized I had a spot, I could not have been more excited. Mom was fine with the idea and gave me permission to play. I did not really know what I was doing, and I was not all that motivated, but it was something to do. I almost never talked about basketball, so when our team went undefeated (7–0), not one person in my family knew about it. Nobody ever came to see me play. Who was I going to invite? To me, it was no big deal. I kept it low-key so that Mom would not feel badly about not being there to watch me. I played the games, had some fun, and made sure that I got home before dark.

The more I played basketball, the more I figured out the game. I was starting to improve, and when my cousin Craigie realized I played basketball, he started taking me to the gym at Victoria Park in Carson almost every day. I am not exaggerating; we rarely missed a day. Craigie was all about discipline. The first time we went to the gym, he had me do push-ups, sit-ups, and all kinds of exercises before I ever got to touch a basketball. I remember thinking, Dang! All I wanted to do was shoot the ball.

He would teach me things and then make me play three-on-three pickup games with the guys. I was unsure of what to do, but Craigie just told me to guard my man. I was already afraid of Craigie; I had seen him fight Braquel. So when he yelled at me, I did exactly what he said. It usually worked out for me just fine. And besides, I remember thinking at the time, Craigie was left-handed like me. That seemed to make it all okay. That made us both a little different than everybody else.

My Uncle Ed helped me, too. He was my mother’s youngest brother, and he took me with him when he played basketball on the outdoor courts at a church in Inglewood. I thought it was very cool that my uncle wanted me to play basketball with him. He would make me play point guard and then have me post up.

Uncle Ed was a totally positive human being and encouraged me to get out there when he could have just as easily said, “Go sit down, Lisa. You can’t play. You’re a girl.” Instead, he challenged me to rebound, block shots, and talk trash. I could get away with trash-talking, too. I knew the guys were not going to mess with me, because I had my own personal bodyguard there. My uncle was six foot three and about three hundred pounds. He used to play football at Southwest Community College, and he was huge, so I felt very safe.

Sometimes I would get pushed, tripped, knocked down, or fouled really hard. Uncle Ed would yell to me, “Get up. Come on. Keep going!” Or he would shout, “You can do it! Go hard! Go strong! Don’t let ’em take that ball away!” It was like when you got bullied at school and your parents told you, “Go back and fight that bully. If you don’t fight him, I’m going to whup you!” That was Uncle Ed’s approach, and it was good for me. I was just learning to play a physical brand of basketball, so his no-nonsense style of encouragement kicked my game up a few notches.

I felt like I belonged in the gym maybe more than I belonged anywhere else. Even though I was a girl, I could play. I was not babied or given any special favors, but there was always a feeling of love and affection for me at the gym, because Uncle Ed and Craigie wanted me to play and gave me a chance. This gave me tremendous confidence. It was a great feeling to find something that I could do well, and it was also very important at that time in my life to have men support me and let me know that it was okay for me to play.

Craigie and Uncle Ed were my only male role models as far as basketball was concerned. I still cannot believe that they spent all that time working with me. I was only twelve years old. They were both closer to twenty. How many guys that age really want to take a young girl to the gym with them? I am sure there were a lot of other things they could have been doing, but their time was just what I needed. I appreciated them so much, and I was thankful for every second that they took out of their lives to be with me. That is why I always tried to be quiet, to not talk back, and to stay out of their way and off of their nerves. I looked them in the eye when they talked, and I listened well. I learned a lot, and I improved. Craigie and Uncle Ed liked my attitude. Craigie set me straight in that department the very first day that he took me to the gym. He sat me down and made it short and simple: “If you are going to have an attitude and want to be in here talking and fooling around, I’ll take you home right now and never bring you back.” Believe me. I got that message loud and clear. I think that made Craigie and Uncle Ed want to help me even more.

Their attention made me feel good. There was no father at home to watch sports with me and explain what was going on. And there was nobody to teach me the game or help me understand the fundamentals. I was just learning to play basketball on the fly—a pickup game with guys here, a practice with my junior high school team there. It was like on-the-job training. Craigie and Uncle Ed were my teachers, and I was their student. Every time we stepped on the court, I tried to learn as much as I could and make them proud.

At the same time that I was learning basketball, Aunt J.C. was teaching me “girl things.” She was the first person to show me how to put Nair under my arms. We would all sit on her kitchen counter while she explained the necessities of underarm hair removal. We walked with books on our heads, and we tried to practice proper etiquette. We worked on the correct way to eat and sit, and we practiced good posture. It was a good reminder of what my mom had already told me. To this day, my friends tease me about sitting up so straight. “You make me sick,” they tell me, “always sitting up so straight!” I do try to slouch sometimes, but after a while I go right back to sitting up.

Mom wanted to make sure that her girls knew what girls needed to know. So while she was on the road, Aunt J.C. made sure we learned. I did not know what being feminine was, but I did know what a lady should do and how a lady should act. For example, I knew that when wearing a skirt, a lady should cross her legs so that no one can see what is underneath. This is why I started wearing shorts under my skirts way back in second grade. It was important to me to be feminine, and I liked taking cues from Aunt J.C. and from Mom when she was home. And it is a good thing, too, because I always wanted to look my best.

When we moved in with Aunt J.C. and she saw my hairdo, I think she wanted to dial 911. Dionne had experimented with a Jheri Curl on my head, and it was not going well. My hair was unhealthy and full of chlorine from the local pool and had turned a shade of orange. You also have to keep getting Jheri Curls every few months, but I was not able to manage it well on my own, and Dionne did not really know what she was doing. I had a dry, orange, Jheri Curl. Something desperately needed to be done to repair the damage, so Aunt J.C. brought in Mike the Hairdresser, who came to her house every Saturday to remedy the situation. First, he would do Braquel’s hair: wash, condition, blow-dry, press, and curl. Then he would do the same for me.

One Saturday, though, Mike did my hair first. When he was done with me and started working on my cousin, Craigie came home and asked me to shoot some hoops with him. We went around the corner and played for about an hour. It was hot, and I got really sweaty. By the time we got home, my fresh do was not so fresh anymore. My hair was all wet and plastered to my head. I was scared to go into the house because I knew that my hair was ruined. I looked like I had been left outside in a downpour. I was seriously afraid of how Aunt J.C. was going to react.

When I finally got up the nerve to walk in the house, my aunt spotted me and shouted, “Oh my God! Look what this girl has done to her hair!” She was irate, but for some reason, she was laughing at the same time. “I can’t believe it,” she said loudly. “You just got your hair done!” She stood there in shock. “We were finally getting your hair back nice and clean. It was just starting to look good, and you go out and play basketball? Why did you mess up your hair, Lisa?”

I did not have any answers for her, but Aunt J.C. had an ultimatum for me. “You are going to choose today, young lady. You can either play basketball or get your hair done, but you cannot do both. Which is it going to be?”

Without a hint of hesitation, I told her softly, “I want to play basketball.”

My aunt looked at me, looked at my messy hair, and then said, “All right. Fine. Put your hair in a ponytail, and go play basketball.”

I knew I had made a big decision that day. I could have said, “Oh, I want my hair done.” Mike probably would have done it again for another ten dollars, but who knows what direction my life might have taken if he had. At that time, being cute and stylish was nice, but it was not my top priority. I wanted to play basketball, so I put my hair in a ponytail and went off to play some more. Honestly, I would have played all day and night if I could have. If Craigie wanted to go to the gym early, I was ready. If he wanted to wait until after 5:00 PM, I would do my homework, eat, and get dressed in a hurry just in case he wanted to leave a little earlier.

I had found a passion for the game. It had become a major part of my life. I loved the sport, and somehow, I knew it was going to be a big part of my future. I wanted to be very good, so I would take what Craigie taught me and then try it out in practice sessions and games. I started to put two and two together. When I struggled, I would go back to Craigie, and he would have a ton of criticism and suggestions for me. I would absorb all that he told me, store it in my memory bank, and try to do better next time. I turned into a perfectionist, and that was not necessarily a good thing. Basketball is a game where you strive for perfection but never, ever get there. That can be extremely frustrating. This did not keep me from trying, though. Striving for perfection made me a better player, which came in handy the following spring, when I joined a boys’ basketball league and played for a team called the Sonics.

I did not get to play basketball at school during my entire eighth-grade year, because I switched schools in midyear, but I continued to spend a lot of time working on my game with Craigie. A guy at the gym named Vic suggested that I join an organized team to remain competitive and sharpen my skills. There was no girls’ team, so I joined the team for boys. I was the only girl in the entire league, and I played in the 14-and-under division. Corey Benjamin, who later played in the NBA, was in my league. Craigie loaned me a pair of his basketball shoes to wear with my brand-new #10 Sonics green uniform. It came with white mid-calf socks that had a green stripe around the top. That was the first “take home” uniform that I ever had. I thought it was very cool, but the uniform was not my size. It was too tight, and I barely fit into it. I wound up wearing very short shorts and a too-snug shirt. I was six foot two, the tallest player in the league, but that was not the only reason I stood out.

At first, the boys on my own team did not want to pass the basketball to me. This really upset me, so on one of our possessions, I intercepted a pass between two of my own teammates and dribbled in to score a basket. I stole the ball from my own team! After that, everybody started shouting, “Give the ball to the girl!” The Sonics soon realized that if they got the ball to the tall girl in the middle, she could put some points on the board and help them win games. They finally listened.

I knew I could play a little, and I soon found out that I could do almost everything that the boys could do. I could jump and block their shots. I could slide my feet and play defense. The boys did have a quickness factor that sometimes left me in their dust, so when I played with them, I really had to focus and play super-hard to stay with them. That extra effort against the boys gave me incredible confidence when it came time to compete against girls. Later, in my professional career, my scrimmages with Magic Johnson and his NBA buddies helped me prepare for the battles I faced in the WNBA. To this day, I like to play with men, because it helps me improve my quickness and my moves. This allows me to be more aggressive and play harder with women.

Someone had obviously been keeping tabs on me while I played on that boys’ team or when I practiced at the gym, because in that summer of 1986, I was selected to play in the Olympic Girls’ Development League (OGDL). It turns out that the OGDL played its games at the same Victoria Park that Craigie had been taking me to every night to work on my game.

John Anderson was my OGDL coach. He gave me the first pair of basketball shoes that I could call my own. They were Nikes. I loved them, and I knew I would like Nike from then on. Mr. Anderson was a yeller, though. And he was the first coach who cursed at me. Sometimes he made me cry, but I think that hurt his heart, because afterwards he was always really nice to me. He would say, “Lisa, when I yell, I am not really yelling at you. I just want to help you get better.”

Even through all of Coach Anderson’s shouting, I could sense his caring personality. He was a real sweetheart, and eventually, I learned not to take his shouting personally. Sometimes, I would even go over to his house to hang out with his daughter, Adana. Mrs. Anderson would cook, and we would all have a good time. The Andersons really took care of me. Since Aunt J.C.’s house was nearby, they would even pick me up for practices and games, and then drop me off afterwards.

I knew Coach Anderson saw something special in me, because he was always on my case in the gym, yet so nice at home. He must have liked my game a lot, because before I knew it, he had me playing in the OGDL’s fourteen-and-under, sixteen-and-under, and eighteen-and-under girls’ divisions, all in the same summer and sometimes all in the same day. I was incredibly busy, but I was excited, too, because Shay had joined the summer league. We would play on the weekends, and when one game ended for me, I would head to the sideline and change into the colored shirt of the next team that I would be playing for. Then, I would get back on the court and start playing again. I could go through a lot of shirts in one weekend. Some days, Shay and I would get to the park at 8:00 AM, and we would play five games before heading home. I loved the competition, and I enjoyed seeing my basketball skills improve with every game.

The OGDL was really great for me. I played against Pauline and Geanine Jordan in the eighteen-and-under division. They were twins who just happened to be two of the best girl basketball players not only in California, but also in the entire country. They were recruited by all of the top college basketball teams. Coaches were constantly coming to watch them play, so the OGDL was a showcase for the Jordan twins. It also shined some of the spotlight on a fourteen-year-old who was playing against them—me! I was not on the twins’ level in talent or experience, but I was competitive enough in the eighteen-and-under games. I had to guard Pauline and Geanine (who both got scholarships to UNLV), and that made me better defensively, but I also learned that I could score against the big girls. I could take them away from the basket and hit a short jumper, and eventually, I was driving to the hoop against them and scoring. It was exhilarating. The more I played, the better I got. The better I got, the more fun I had. And the more fun I had, the more I wanted to play.

My metamorphosis on the court was incredible. Within two years, I went from having never played basketball and nervously trying out for my seventh-grade team to holding my own on the court against eighteen-year-olds. I improved so much so quickly, and much of it was due to the basketball mentoring that I got from Craigie. He made sure that I knew the basics, and I made sure that I worked hard and put his teachings to good use. It was all coming together. I was finally really good at something, and I kept growing taller, too. I was up to six foot four that summer, but I was no longer Olive Oyl when I stepped on the court. I was Lisa Leslie, basketball player. I had an identity. I was not awkward. I could move. I performed, and people liked the way I played. My confidence was so high that it did not matter to me what age or gender my opponents might be. In my mind, I had the upper hand on all of them. It was a fantastic feeling.

My schedule was grueling, though. It was all basketball all the time for me, and since it was the summer, I had lots of time. I practiced two nights a week with the OGDL and then played their games on Saturdays and Sundays. I also played two games during the week with the Miraleste High School squad. Mom was trying to transition into more local trucking work, and she wanted to move our family from Carson to Palos Verdes, which was a nicer area. Miraleste High was located in Palos Verdes, so it made the most sense for me to play with the high school girls that I would be joining in the fall. I did not complain; their team was super impressive. We played against athletes like Heather and Heidi Buerge, another set of twins. They were both six foot four, just like me, and they both went on to play in the WNBA, just like me. The Miraleste squad had twin girls who mirrored the Buerges, plus we had a six-foot-seven center, and our point guard was over six feet tall. Our starting lineup featured five teenage girls who were all at least six feet tall. We were expected to have a great season. But as it turned out, I was not going to be a part of it. Mom decided that the move to Palos Verdes would be too much, too fast, and too expensive to handle. So instead, we moved from Aunt J.C.’s house in Carson to my grandmother’s house in Inglewood, not far from where the Lakers played NBA basketball at the Fabulous Forum.

That meant that Miraleste was out of the picture, and I would be attending high school in the Inglewood district. The Inglewood district had two high schools at the time: Inglewood and Morningside. I knew absolutely nothing about either of them, but Inglewood was a little closer, so Mom decided to enroll me there. On the day of enrollment, Mr. Dillon, the man in charge of Pupil Personnel Services, made a point of coming over to talk to us. “I know you want to go to Inglewood High because your Uncle Ed went there,” he said. “But I really think you should consider Morningside High. They have an excellent basketball team and a great coach. His name is Frank Scott. He takes good care of his girls, and he makes sure that they get home safely. I would really advise you to consider Morningside.”

I did not have a preference. I just wanted to get a good education and play basketball. But right then and there, I decided to attend Morningside High. It turned out to be one of the best decisions of my life.

Before I ever stepped one foot on the Morningside campus, I had already received more than a hundred college recruiting letters. I was only fourteen, but my game had improved so much over the summer that college coaches had taken notice and were lining up to let me know that they were interested in me playing basketball at their universities. I was only an incoming freshman and I had not played one second of high school basketball, but I got letters from everywhere, including top Division I basketball programs, like Stanford, USC, Notre Dame, and Tennessee. Harvard wanted me, too. But being highly recruited did not help me fit in.

I was shy to begin with, and I always felt like an outsider, which only made things worse. I hated the fact that I did not grow up in one place, where I could really get to know people. How could I? I went to three different junior high schools. I think that is a big reason why sometimes people misinterpreted my shyness as being closed off or snobby. This still occasionally happens. I have always tried to treat all people nicely, but I am not very good at opening up to people. Growing up without close, long-term friendships made me a loner in a lot of ways. I never had to have a million friends, but it would have been nice to have some of my close friends for more than one school year. I was always the new kid. I was never the outcast, but I was never in any one school long enough to get into the in crowd and at times I felt left out.

My life changed dramatically, though, once I got to Morningside. On the first day of school, I was sitting all by myself on the last bench in the entire lunch area. I did not know one person. I was wearing a long pink skirt with checkers on it, a pink blouse, and black shoes. I had a ponytail and bangs. I was in high school, but I did not have a clue how to dress. A group of girls walked up to me, and one of them asked, “You play basketball?” I found out later that her name was JoJo Witherspoon.

I said, “Yeah. I play basketball.”

They ran off, and a few minutes later Coach Scott came over to introduce himself.

“Hi, I’m Frank Scott.”

“Hi, I’m Lisa.”

He knew who I was. Coach Scott had seen me play for Miraleste during the summer, so I think he was really surprised to see me sitting in front of him right there at Morningside. Just about everybody expected that I would be part of that powerhouse team in Palos Verdes.

“I hear that you play basketball,” Coach Scott said. “Would you like to play for our team here at Morningside?”

I told him I would.

“Are you good?” he asked, with a smile.

I answered, “I don’t know, but I want to play.”

Coach Scott chuckled. “Okay,” he said. “Good. Meet me at the gym at two PM.” Then he brought me over and introduced me to some of the other girls on the team. I was shy, but I was very excited.

I was in ninth grade—a brand-new freshman—but adjusting to a new high school was not my only concern. Tiffany and I were now staying with my grandmother. She was my mother’s mother and was so young looking that we called her Dear instead of the older-sounding Grandma. Dear’s house was another new place for us, another sofa bed to sleep on, another set of rules to learn. Every morning Dear would get up around seven o’clock and start yelling, “GET UP! GET UP!” Then she would start playing gospel music and run the vacuum cleaner. There was no sleeping late at Dear’s house—not even on weekends.

Tiffany and I would wipe the sleep from our eyes, stumble to our feet, fold up our blankets, fold the sofa, and then just sit there. There was absolutely no reason for us to be awake. We were sleepy, but my grandmother wanted us up, so we were. It was just miserable. I was always panicky at my grandmother’s house, constantly making sure that Tiffany did not make any messes or cause any trouble.

Dear would say, “Get your sister dressed, and get yourself dressed, too.” That meant I had to shower, bathe Tiffany, get her dressed, and have her all ready to go NOWHERE! My grandmother just wanted Tiffany to be up and dressed. Today, as an adult, I understand that kids do not need to stay in bed until noon or hang around in their pajamas all day, but it sure would have been nice if Dear could have held off on the wake-up calls until at least eight o’clock.

Once again, I found myself talking under my breath. “Oh man! I cannot wait till Mom gets home so we can get out of here.” Then a different thought would pass through my mind. Man, I cannot wait to get out of here so I can go play basketball. Hoops had become an outlet and my exciting new escape. I had just one small roadblock: my grandmother.

Dear was very hesitant to let me play basketball at my new high school. She was protective of me and did not want me to be take advantage of me. Coach Scott came by the house to introduce himself, and Dear was defensive and downright rude. She asked him point-blank, “Who are you, and what are you doing over here? What do you want with my granddaughter?”

Coach Scott seemed to understand my grandmother’s dubiousness and responded in his usual calm, respectful, non-ruffled way. “I am the coach of the girls’ basketball team at Morningside High School, and I would like Lisa to play on our team. I would be happy to come by and pick her up for school in the mornings and bring her back home after practices.”

Dear’s interrogation continued. “How do I know I can trust you?” I was so embarrassed. Looking back on it now, I know that she was just looking out for me, but Dear was really working Coach Scott over. She had no idea who this man was or what he might have in mind for me. But Coach answered her questions politely and gave her a lot of references and phone numbers to call so she could check up on him. Coach Scott told my grandmother that Mr. Fortune, the superintendent of schools, and our principal, Mrs. Martin, would verify that he was a good man who had been at Morningside High for ten years and that he routinely picked up his players before school and dropped them off after practice, without any problems at all.

Coach Scott withstood all of my grandmother’s blistering inquiries, and he turned out to be one of the most invaluable people in my basketball development. He would pick me up for school every morning. I would go to class, participate in girls’ basketball practice from 2:00 to 4:00 PM, and then practice with the boys’ team until Coach Scott was ready to leave. On some days, I would stay with Coach Scott to work over and over on my post moves. He would have me dribble in and take a bank shot. I would drive to the left, drive to the right, and hit a jump shot. He taught me how to react when a shot was taken, and how to box out, grab a rebound, and slide my feet to play more efficient defense. He was very good with fundamentals and very good for me. My knowledge of the game and my work ethic improved rapidly.

After practice, he would drive several players home. I actually lived the closest to school, but he always dropped me off last. I begged him to so I would not have to spend too much time at my grandmother’s house.

I enjoyed hanging out with him. I still do to this day. Coach Scott would tell corny jokes, and I might have been the only person who laughed, but I thought he was so funny and cool. In a lot of ways, he was the father that I never had. He was a very mellow, soft-spoken man who knew the game and knew how to communicate it to me, but he cared about me as more than just a basketball player. Coach Scott was the only one who knew that my mom was not home and that my sister and I were living with my grandmother under intense conditions. He would check my grades and make sure that I was eating lunch, and he would talk with Mom all the time to assure her that I was doing well. He was interested in me. I was flattered, and I did not want to let him down in any way.

Coach worked with me constantly. He would make me take five hundred shots a day and work on my dribbling. He taught me how to use my height to my best advantage. He would lob the ball up high to me and have me practice my turnaround jump shot. It was catch, turn, and shoot without my ever bringing the ball down below my head, where a smaller defender might grab it. I would do that left-handed, then right-handed. I would do the George Mikan drill over and over: left-side layup with the left hand, rebound, right-hand layup on the right side. Up and down, side to side, and back and forth time after time after time. It was difficult, but that drill helped with my footwork and rebounding, and I was able to get shots off more quickly.

Coach Scott never stopped challenging me to improve. He would bring a broom out on the court, hold it straight up over his head, and try to block my shots with it. That forced me to put more arc on my shots, which really helped when I competed against other tall players. He would line up my teammates and have them dribble and drive at me, one after the other. My job was to block every one of their shots. It was hard work, a real test, but it all paid off. Whatever Coach Scott told me to do, I did. I was not about to cheat myself. I did not cut corners. I worked hard and I got better. Some of the other girls on our team would talk back to Coach Scott or chatter during practice. I did not give him any attitude. I listened and I learned.

I did not talk much with my teammates. I had first lunch period, and most of the other girls had second. I rarely saw them during the day, but then, after school, I had to compete against them in order to win a spot on the team. Everyone was talking about who the starters might be, and more than a few times, I heard someone whisper, “That new girl is not going to come in and take my spot.”

It was an awkward situation, but as much as I wanted to be accepted, basketball mattered to me more than going out of my way to be anybody’s friend. I had very little competitive basketball experience under my belt, and I had never seen any of my new teammates play. I had no idea what level they were on. My gut told me to just go out and work hard. I definitely knew that I was tall. That was a big plus. I also knew I could shoot and play defense, but I had to learn in a hurry to be competitive. There was no cockiness to my game, because I knew that I had arrived so late to the sport. I knew there were other girls on the team who had played a lot more than me, and I knew that someone out there might be better than me.

As it turned out, I was pretty good. Much better than I thought I would be, at least. I understood the drills and the three-man weave, and I was gaining more confidence day by day. I worked on dribbling, on blocking shots, and I kept improving. I was a freshman, but I was challenging Shaunda Green, a junior, who was the best player on our team. She was coming off an All-California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) season. There was jealousy and some tension in the gym. My teammates were not very discreet when they would say, “She ain’t better than Shaunda. She’s not going to come in here and start.”

My mind-set was, I am here and I can play basketball. I am not going to back down from any player, no matter her talent level. If Shaunda Green was the best on the team, then that is who I wanted to play against every day.

So I was very goal oriented early on. This was just the ninth grade, and I was already writing my goals down, knowing it would help me achieve them. I wanted to get better in math and earn a 3.5 grade point average, and in basketball, I wanted to be “Freshman of the Year” in California. My thinking was simple: This is what I want to do. This is what I want to accomplish. And I was so serious about it. On the basketball court, I planned to be the very best that I could be, and it was not just a dream or a wish. It was something for me to work toward, and my efforts paid off. I was the only ninth grader to make the varsity team. Shaunda and I were teammates. We were both very good, and we played well together for Morningside.

My high school basketball career was off to a great start, but six-year-old Tiffany was still my responsibility. I still had to pick her up when she got out of school. Then both of us would go to my practice or game. When the Lady Monarchs traveled, Tiffany would be on the team bus with us, even though that was strictly forbidden. Tiffany would write and keep busy while I did my homework, and I always made sure she got something to eat.

When I had games, Tiffany would sit by herself in the stands. While I was on the court playing, I would glance over from time to time to make sure that she was all right and to make certain that nobody had kidnapped my little sister from the gym. Tiffany was at Morningside High more than some of the students, and she was with me for almost every one of our road games, too.

It was a lot of responsibility for a fourteen-year-old, but somehow Tiffany and I both made it work. She was a healthy, happy, resilient kid, and she thrived in spite of our very unusual circumstances. So did I. I averaged twelve points, nine rebounds, and five blocked shots, and the Monarchs finished with a 27–3 record during my freshman season. And my grades were good, too—mostly As and a few Bs. I was named “Freshman of the Year” in the state of California. The sense of accomplishment I felt tasted so sweet! But it was just the tip of the iceberg.