Читать книгу Cool Flowers - Lisa Mason Ziegler - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTwo

THE LIFE OF A HARDY ANNUAL

It’s a cold crisp morning in early spring and I’m walking the farm, eyeing the handiwork of fall and late winter. The hard work of preparing soil, starting from seed, planting, and mulching is nothing more than a faded memory as I admire the tall, sturdy snapdragons, their buds ready to burst open. I can hardly take my eyes off the snaps until I notice the sweet pea patch. New little shoots of sweet pea vines are popping through the soil surrounding the baby vine I planted months earlier. The little vine I planted in the fall now appears wind-whipped and exhausted. However, I take heart in knowing that the frostbitten sweet pea vine planted long ago has done its job. It has fostered a root system through the winter that has grown into a well-established and strong foundation for this late spring bloomer to soar on. It brings a grin that is hard to lose when I think of those sweet pea vines and snapdragons riding out the coming days, blooming like crazy, even in the midst of heat and humidity.

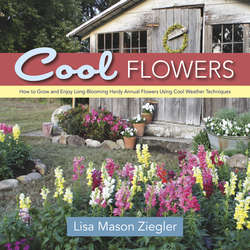

A spring bouquet of hardy annuals.

These early season walks in the garden, allow me to explore and enjoy my garden in a new way. It is still chilly, but warmed by the bright afternoon sunshine. I investigate, pull a weed here and there, and even cut an early-bird bloom to bring in the house. Just a single bloom from the garden in late March and early April takes a place of honor on my desk. Then I carry it to our kitchen table so we can all enjoy the message this bloom is bringing: spring is on its way.

Before I discovered hardy annual gardening, my gardening experiences in late winter and early spring were more about scouring the gardening catalogs as they arrived and just dreaming. Now, it’s as if I have been given yet another season in my garden to enjoy.

The Notions of Spring

One of my first hardy annual gardens that included; snapdragons, love-in-a-mist and corn cockle.

The lifecycle of a hardy annual is an oddity to most gardeners. It seems unreasonable to expect anything from seeds or plants put out in the garden when cold weather is just over the horizon, or in early spring while it’s still frosty and chilly like winter. It just doesn’t make sense. But the truth of the matter – the secret – is that hardy annuals are cut from a different cloth than that of our tender warm-season annuals (the ones we think of when we hear the term “annual”). And that’s why we must garden differently if we want these beautiful hardy annual blossoms in our gardens.

At-a-Glance

• Hardy annuals live for one year and survive cold temperatures. Many are planted in fall to winter-over and produce blooms the following spring and summer. These flowers prefer growing in cool conditions.

• Tender annuals live for one year and do not survive cold temperatures. These flowers are planted after the threat of frost has passed in spring and the soil has begun to warm. Tender annuals prefer growing in the heat of summer.

Pansies are among the most popular and widely planted spring bloomers. They are hardy annuals. Planting pansies in fall and late winter for the best spring blooms has been common practice for a long time. I like to refer to pansies as the “kissing cousins” to all the other hardy annuals, only related because they enjoy the same type of growing conditions. So, just think of pansies for a moment while we wrap our heads around this concept of hardy annual gardening.

Why is it so tough to grow these spring bloomers? Here’s why: in most gardens, spring comes on quickly and moves right into summer. It doesn’t hang around long enough to accommodate our natural gardening instinct to plant spring bloomers in… well, spring! We naturally think spring should be like summer. We plant summer bloomers in summer once the warmth starts, and then they grow into valuable members of the long, leisurely summer garden.

Following suit, we storm the garden on the first days of spring with our seed packets, plants and trowels to plant some of the beauties of spring. But it’s too late. Spring flowers don’t work that way. The window of opportunity has long passed, and our efforts are short-lived and frustrating. We never get the gorgeous display we are promised, because we are planting during the time that this group of flowers is being asked by nature to perform with wild abandon. New little plants just can’t do that.

Hardy annuals naturally develop and grow into strong plants when they have opportunity to do it during cool conditions. When these plants get the great start that cool weather provides, their stamina and ability to perform makes you wonder why you didn’t think of this sooner. It’s all about getting the plants started and established during their preferred growing conditions. Once they are well established, hardy annuals seem to look adversity in the face and bloom even more. What I said in the introduction bears repeating: plant them in the right spot, at the right time, nestle their roots deep into rich organic soil, and stand back.

What is a Hardy Annual?

The term hardy annual indicates a plant that typically lives for one year and doesn’t just survive the cold, but thrives under cooler temperatures. Both plants and seeds can be planted in the fall, winter and/or early spring depending on your region. In a large portion of the country, hardy annuals can be fall-planted to winter-over as immature plants. This allows them to establish an incredibly strong root system that gives the earliest possible blooms in spring and keeps them performing well into warm and hot weather. In more northern zones where there are frigid conditions or heavy snow loads, these flowers can be planted in the very early spring while waiting for warm temperatures to arrive. For those who plant in the fall, a repeat planting in very early spring can extend the blooming season; we do this with excellent results on our farm here in southeast Virginia.

As a general guide, hardy annuals can be planted 6-8 weeks before the first frost of fall, to winter-over as an immature plant, and/or planted 6-8 weeks before your last frost in spring. When you plant depends on where your garden falls on the hardiness zone map (page 138). Getting this better understanding of what makes hardy annuals tick will help you to tweak these guidelines even more to suit your garden. I encourage you to be bold and experiment with flowers that may thrive just outside of your zone; sometimes those results are the sweetest of all.

Bachelor buttons holding their own as the snow cover melts away providing a deep slow watering.

The life cycle. The hardy annual’s natural life cycle is to go from seed into making seed in the span of one year. The annual plant’s whole purpose in life is to grow into a plant to produce flowers that will produce seeds – and then die. The confusion with hardy annuals comes because their year of life follows a different calendar than we are accustomed too. They begin life from a seed in the fall, then winterover as a young plant, becoming well established so that when spring arrives, they quickly grow into a robust plant. Their life cycle continues as they bloom, make seed, and die.

This is why, once your plants start producing flowers in spring, you have a choice to make. On the one hand, you can remove the flowers as they bloom by either harvesting them for cut flowers or dead-heading once they begin to fade. This way, you will keep your plant producing more and more flowers in an effort to get those seeds made. However, if you choose to leave the faded and dead flower heads in the garden, they will develop into seeds. At that point, the blooming will cease because the plant believes its job is done and it’s time to die.

Knowing what the hardy annual is programmed to do can help you get the most from your plants in a profusion of continuing blooms. Here on our farm, we cut the flowers weekly to have as fresh cut flowers. This routine harvest keeps most of the plants blooming long after their expected time. Your course of action will depend on the purpose of your garden. Is it a cutting garden, a container for display, a landscape to enjoy, or a bed to attract birds and pollinators?

Other Plants You Can Grow as Hardy Annuals

Delphinium are a perennial in the north, but gardeners in the lower half of the country can grow them as hardy annuals with great success.

In this book you will also learn about some plants known as perennials and biennials that can function better in some gardens as hardy annuals. Doing so brings satisfaction and success where it may not have been possible before. Growing conditions make some perennials almost impossible to maintain year-round. But they may be perfect additions to the garden when treated as a hardy annual. A great example of this is the delphinium. In the northern regions, delphiniums grow into amazing plants that return year after year. In other parts of the country, we can grow fabulous delphiniums by treating them as a hardy annual. The heat and humidity of our late summers weaken the delphinium so that they fall victim to disease and pests. It is liberating to the gardener to know when to plant these flowers so they can perform at their best. The gardener can work with nature to plant in the fall, look forward to a strong performance in spring and summer and then, when late summer arrives, accept their ultimate demise. New seedlings can be planted in fall for the next season.

‘Virgo” feverfew is my favorite because of its tight cluster of button blooms.

Another time that we treat a perennial as a hardy annual is when it is not a particularly strong or long-lived plant. Such plants are often called a half-hardy perennial. Feverfew follows this habit, a great garden plant that flowers from seed the first year. In subsequent years, it either disappears or loses its attractiveness in the garden. To prevent suffering an untimely loss or experiencing a hole in the garden, we grow feverfew as a hardy annual, replanting yearly in the fall for a profusion of button blooms every spring.

A biennial such as foxglove can also be grown as a hardy annual. This allows you to eliminate much of the growing time normally spent in tending and caring for a plant that will not bloom until the following year. Biennials are not as widely grown because of this long time-lapse to get results. Traditional seeds are sown in late spring. The plant must be tended all summer and into fall to have it go through winter and produce blooms the following spring.

But growing foxglove as a hardy annual is different. You start plants from seed in late summer, allowing the immature plant to winter-over, and then watch the plant bloom the following spring. This way, you have eliminated months of plant care during the heat and possible droughts of summer.

Easy to Get Started

Many hardy annuals prefer to have their seeds cast directly in the garden. The fall and early spring seasons often tend to our seeds better than we do. This is the best time to get acquainted with planting seeds in the garden, because it is the most forgiving time. There is a little rain and snow just when it is needed, along with cooler night temperatures and some warm days. All of this makes perfect growing conditions for our seeds. Add to this the benefit of the winter rains and snows, and they will thrive with little attention from the gardener until it’s time to bloom. Some will cast their own seeds in the garden to return year after year. Once your plants begin to cast their own seeds, you can take your cues from Mother Nature when to plant. Some of the greatest lessons learned have come from mimicking what nature does, and when.

Bells of Ireland baby plants that wintered over. I planted their seeds directly in the garden the previous fall.

The seeds of many hardy annuals can also be easily started indoors. It is sometimes more practical to do this and then move the transplants into the garden. Because mulching can be done right away when planting, it reduces the need for weed prevention chores and can widen the window of times to plant. A nice bonus to starting indoors is the comfort of the gardener on hot summer or cold winter days. In the dog days of late summer, I thoroughly enjoy heading indoors to start seeds for fall planting.

On a visit to my friend Dave Dowling’s flower farm, Suzanne and I discovered these gorgeous delphiniums ‘Pacific Giants’.

In my experience, one of the greatest struggles of late winter is to resist starting tender annuals such as zinnias and sunflowers too soon. These warm season plants become overgrown and unhappy waiting for the soil to warm for the proper planting time. Starting hardy annual seeds to be planted into cool soil fills that urge perfectly, and helps the gardener wait until the proper time to start tender annuals.

Growing hardy annuals is especially appealing because you prepare and plant them at a time when little else is going on in the garden. Preparing the garden becomes a pleasure as you tackle the task during the fall when cool nights and shorter days have arrived. If you are planting both in the fall and in early spring, the soil should be prepared in fall. Winter rains and snow make it difficult to find a dry spell to dig in the garden for early spring planting.

A Haven for Pollinators

With your hardy annual garden you’re going to notice the vast number of early season “good bugs” buzzing around. This would include native bees and many other pollinators. Because there are so few sources of nectar and pollen this early in the season, hardy annuals really provide for these guys when they need it most. This also gives my garden an early start on building the community of beneficial insects that are essential to our organic gardening success. While many gardeners are aware of the benefits of the most popular beneficial insect, the ladybugs, there is a whole army of others that help our gardens as well. Many of these beneficial insects are searching for food and a place to live and raise babies in spring. A garden planted in fall, winter and/or early spring is a perfect fit for them.

Watching and Waiting

The anticipation I experience waiting for this garden to pop full of blooms during the winter and early spring compares to little else. All winter I watch from the window, wondering about those little plants I planted in fall. Will they survive the whipping winds and below-freezing temperatures? The snow? Yes, they do survive, they really do. This scenario plays out in my mind every year. Perhaps the scariest thing I do in January is to go out and take a closer look just to see what is going on in this garden. It’s always the same; I am met with frozen, tattered plants that look like they will never live to produce a bloom. Panic sets in. Then I remind myself that the most valuable part of the plant at this time of year is the root stretching and going deep underground, hiding away snuggled in rich soil and protected with mulch. My heart leaps for joy every year when I see the first little green shoot pushing up next to that tattered plant.

The blooms of this black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia ‘Indian Summer’) are often larger than your hand.

Pincushion Flowers

There are so many aspects of a hardy annual garden that are empowering to gardeners: you plant when little else is going on in the garden; it is cooler; rain is more frequent, eliminating watering chores; and the act of fall planting introduces a new feeling of anticipation for spring. Waiting for this group of flowers to jump into action in spring is so exciting. I find myself snooping around the garden just looking, wondering and waiting. I could stay out there for days cuddling these plants – even though they don’t require it! I know that for the rest of the winter they are ready and waiting to perform for me. That is just one of the many reasons I love to garden.

Once you understand this fascinating, easy, and beautiful group of flowers, I think you will be hooked too.