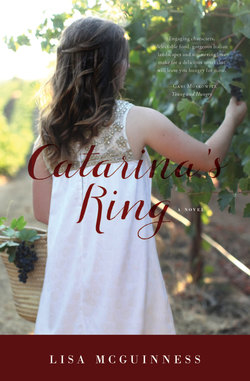

Читать книгу Catarina's Ring - Lisa McGuinness - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

JULIETTE, THE RING, FLEEING TO A BEAUTIFUL ITALIAN CITY AND TRYING TO COOK AWAY SORROW

“She wanted you to have the ring, Juliette,” her father Alexander said, holding out the perfect diamond ring that had belonged first to her grandmother, then her mother, and now, horrifyingly too soon, to her.

Juliette looked over at Gina, sitting beside her at the table in her parents’ kitchen, who nodded, obviously already having been told this news.

“Why me?” she asked, again looking at Gina who was older. Juliette had always assumed the ring would go to her.

“Mom left her share of the business to Gina,” their father explained. “That’s her heritage and connection to your grandparents. She left the ring to you so you would have a connection as well.”

Juliette’s hand shook as she took the ring from her father.

“I can visualize it on both of their hands,” Juliette said, tears slipping down her cheeks. “I’m not ready for it to be mine. I want it to still be on Mom’s finger.”

“I know,” her father said, and ran his hand over Juliette’s long light-brown hair. It was shot through with gold threads and was a sharp contrast to her sister’s loose dark brown curls that were so like their mother’s. His two daughters were physically dissimilar and yet there was something that gave them away as sisters in spite of their differing looks.

Juliette was tall for the family—more lanky to Gina’s petite frame that was like their mother’s and grandmother’s. Juliette took after the Brice side, whereas Gina looked like a Pensebene through and through. Except for their eyes, which they had each gotten from the opposite sides, to complete their heritage. Juliette’s were the same as her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, whereas Gina inherited her father’s hazel eyes. The sisters were an interesting contrast, yet both beautiful in their own ways.

She had been feeling detached and numb since the accident. Sitting next to her father and holding hands with her sister Gina during her mother’s memorial had felt surreal. The sorting and cleaning out of her belongings was even worse. It made the loss jaggedly permanent. Choosing some of her favorite things to keep seemed wrong, but her dad and Gina insisted so that there would be no regrets later about things lost or given away hastily in a moment of rash grief.

It had felt almost businesslike yet Juliette had felt like she was drowning.

During the weeks following Amilia’s death, Juliette’s mind often drifted towards the box of letters her mother had given to her. She had tucked the plane tickets inside the box with the letters when she had gotten home from the hospital after the accident, but hadn’t been able to bring herself to open the lid since. The box sat on her bedside table, under a stack of novels, and she invariably found herself glancing over at it every night before she clicked off her light until finally one night she reached for it and slipped off the lid.

Juliette scooted herself up until she was leaning against the pillows by the headboard, took the tickets out, and ran her fingers over them, thinking about her mom’s beautiful face when she had given her the early birthday present. They had both been so excited to go and had talked through travel ideas while they had eaten.

It felt like the world had tilted on its axis since that warm moment in the restaurant. Juliette took out the same letter she had looked at when her mother had given her the letters to read. It was from her grandfather to her grandmother when she still lived in Italy before they married. She gently slid the letter out of the envelope and unfolded it, looking at the words written in Italian. She lifted the letter to her face and inhaled, but she only smelled paper and ink—all traces of her grandmothers’ scent long gone.

Juliette had been fairly fluent in Italian when she was younger and her grandparents had spoken to her in the language. She had loved the sound of it and had taken it in college as well, but hadn’t said a peep in Italian for years. Nonetheless, she was pleased to see that she could make out most of the words in the letter, even though the language style was from another era.

That night, Juliette only got through the first few paragraphs before the tears blurring her vision became too much to continue. She carefully replaced the letter in its envelope, making sure not to get the paper wet from her tears, and then turned out the light. A huge, full moon shined through the window and she wondered what life had been like for Nonna Catarina when she received the letter from her grandfather.

The door chimed as Juliette walked into the Pensebene jewelry store and waved to Gina.

“What a nice surprise,” her sister said, and came to give her a hug. “Come in and sit down.”

“I brought us coffee,” Juliette said, handing her sister a latte from their favorite indie coffee place.

“Yum, thanks,” she said and took a sip. “Mmmm, perfect.”

Juliette set her bag down and plopped onto one of the stools at the counter while she looked around.

“The place looks great, Gina.”

“Thanks, but I haven’t changed anything.”

“That’s part of what looks great. I love the fact that I can come here and besides a few updates over the years, it always looks the same. How many times have I sat in this chair, for instance? I can’t even count the number.”

Gina looked at Juliette with a mixture of curiosity and concern.

“I used to love sitting here, watching Mom and Granddad working on designs. And now I can come and watch you, too. It’s nice. Unusual in this day and age.”

“Are you OK, Juliette?”

“What do you mean? I’m fine. I just stopped by because I met a friend for lunch at the Ferry Building and had some extra time to come by and say hello.”

“Oh, nice,” she smiled. “Have you been sleeping any better?”

“No,” Juliette said, looking away. “The moon was really beautiful last night, though. I must have stared at it for hours.”

“That’s something, I guess,” Gina gave her sister a sympathetic look.

“Do you remember the box of letters I told you about? The ones Mom gave me the day of the accident?”

“Yeah.”

“I read part of the first one last night. It was amazing reading words written from Papa to Nonna, knowing it was from such a long time ago. How much life happens and then. . . gone.”

Gina glanced at Juliette again, not at all sure her sister was coping. She sometimes worried that Juliette’s neck and shoulder muscles had become completely rigid from the tension in her body since the accident.

“Do you mind if I keep them?” Juliette asked.

“The letters? Not at all. My Italian’s horrible anyway, but let me know if you discover anything juicy,” she smiled, thinking of their grandparents.

“Mom said it’s mostly between Nonna and a friend of hers.”

“Maybe Nonna was leading a double life. Or was a spy during World War I.”

“I wouldn’t put it past her,” Juliette said.

Gina frowned again at Juliette’s lost look and asked, “Why are you biting your thumbnail and staring into space?”

“I’m just having a thought,” she answered, thinking about the plane ticket tucked inside the box of letters.

Before Juliette told her family about her plans, she enrolled in the Italian cooking class she’d been coveting for ages so she had a justifiable reason to leave. She knew that would help convince her dad and sister that she would be all right and that she wasn’t truly going off the deep end. It would give her days an anchor. She knew they’d been worried about her. They were convinced she was still in shock and Juliette guessed they were right, but whether she was or wasn’t didn’t make a difference as far as she could tell. It was simply a label; but what did it mean from a practical standpoint? It’s not like she could jumpstart herself into feeling normal again. Nothing could bring her mother back.

At home she couldn’t sleep because when she closed her eyes she could see the car coming and feel the same horrifying sensation of being rooted in place, watching it happen. She would turn, wanting to react, but would be frozen while the car careened toward her mother again and again. She saw the impact over and over. She hated being able to remember what was on display in the store, as if her mind cemented those details in place while she simultaneously saw her mother being hit by the car, flung at the window, and finally land on the ground.

So she’d decided to flee from the sympathetic eyes of her friends and family, her in-law studio, the catering job she hated anyway, and enrolled in a cooking class in Italy to get some breathing room. If she could breathe again, and sleep, she thought maybe she could come to terms with what had happened.

Now, weeks later, while Juliette was still mourning the loss of her mom, the ring rested on the middle finger of her right hand as she swung open the heavy black door to the flat she’d rented in Lucca, Italy. Juliette had decided to wear it always as a symbol of strength and perseverance. She thought her nonna, who was the first to wear it, would have wanted it that way. She subconsciously twirled it for strength as she peeked through the open door. She was exhausted as she dragged her heavy suitcase inside and looked around the tiny apartment she’d be calling home for the next six months.

Juliette stepped over the suitcase and let her eyes adjust to the interior light of her subleased apartment. It was dimmer than outside, but sunbeams streamed through a window that opened out onto a metal balcony spilling over with scarlet geraniums. She walked in further and was relieved to see that the apartment was more than fine. It had a tiny kitchen with a two-burner stove that would probably be deemed an illegal fire hazard at home, but seemed a perfect fit here. The bathroom was miniscule and entirely covered—including the floor and ceiling—in orange seventies-era tile, and the showerhead stuck out of the side wall with no enclosure, but she didn’t care.

The wooden floors of the main room were laid in a traditional herringbone pattern and the walls were an off-white plaster with photographs of the surrounding sights. Thankfully there were no bugs in sight. The furnishings consisted of a small, round, dark-gray marble table with two black-painted wooden chairs by the window, a red linen sofa and a tall, beautiful, dark-chocolate colored armoire that made the room look richly furnished, in spite of its small size.

The armoire was exactly the type of piece her mom would have loved. She sighed, running her hand along the smooth wood. When she tried to open it, she realized it had a false front. What looked like drawers at the bottom and cupboard doors at the top was actually one large door that pulled open and inside was a Murphy-style pull-down bed.

Tucked onto shelves at the top of the armoire were sheets and a heavy down duvet with a plain white linen cover that smelled of lilac and starch. The fluffy down was thicker than she had ever encountered at home and the thought of snuggling under it was exactly what she wanted to do in her travel-weary, emotionally-exhausted state.

She liked the look of the apartment. It would be a cozy place for her for the next half year, where she could avoid soothing words and pep talks.

She went back down the steep stone staircase and brought up two smaller suitcases, dropped them in the middle of the room, pulled down the bed, made it, flopped down in her clothes, and was asleep instantly and dreamlessly for the first time in the seven weeks since the accident.

She awoke, disoriented, to the sound of Italian being shouted outside her window and the realization that she was starving. The angle of the sun told her she’d slept for hours and it was now afternoon. She sat up and looked at the clock, then kicked off the covers, threw her clothes into the corner, and took a long, hot shower.

While she shampooed her hair, she did a quick calculation and realized that because of traveling and the time change, she had skipped breakfast and lunch altogether and was now way overdue for a meal. She remembered the pastry she’d eaten half of at the train station, which she could finish now to tide her over, but she wanted some real food and soon. She had seen an open-air market in the main piazza from the taxi window on her way from the train station to her apartment and hoped the vendors were still open.

She would need to set up her kitchen and make dinner, so once she was out of the shower and dressed, she used the back of her train ticket to scratch out a grocery list of milk, tea, coffee, garlic, thyme, artichokes, cheese, wine, and bread among other essentials.

She quickly dried her hair, then threw it into a ponytail and ventured out to stock her kitchen. She thought she might even pick up some flowers to make it cheerful inside. She meandered back to the market she’d seen with only two wrong turns, which for the directionally-challenged Juliette was a triumph. As she walked under the stone arch that formed the entrance, she noticed that the piazza she’d spied was not the main “square” at all, but a circle. It was surrounded by shops and restaurants, strewn with parked bicycles here and there, and hosted a large farmer’s market, which was the perfect place to begin. It was good to be someplace altogether different where she could focus on new sights and sounds instead of on her sadness and unbridled fury at both the out-of-control driver and herself.