Читать книгу The City of Musical Memory - Lise A. Waxer - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеMy husband, to whom this book is dedicated, likes to recount an anecdote about the Brazilian crooner Miltinho, who gave a concert in Cali in 1983. The singer was much loved by local audiences for his three albums of boleros (love ballads) in Spanish, produced in the 1960s. Long retired from music and with faded, patchy memories of the boleros and scores of other tunes he recorded in his lifetime, Miltinho valiantly tried to remember the lyrics to his old hits as he sang before his expectant Caleño (Cali-based) fans. Each time he began a song, however, memory failed him, and he could not complete the tune. To his surprise, the audience—who had memorized his songs by heart from the recordings—took up where he left off and finished each song in chorus from the rafters. The old man, stunned and overwhelmed by the loving tribute of his fans, wept openly onstage.

I love this story, because it—along with many others that unfold on the pages of this book—embodies the powerful ties between musical memory and recordings in Cali. While conducting field research in this Colombian city, I often heard it said that Cali was “the city of musical memory,” and nearly everything I encountered in my study of local popular culture drew me back to this point. More familiar is Cali’s vociferous claim to be “the world capital of salsa.” Colombians are also familiar with Cali’s slogan as “heaven’s outpost”—a pleasure hub of fantasy and alegría (happiness). The first saying, however, is the most potent. To anyone fascinated by sound recordings and their capacity to generate links to new, imagined spaces—past or present—the Caleño obsession with records offers a particularly potent vein for ethnomusicological study. For instance, many Caleños assert that they are “Caribbean” despite their geographic distance from its sparkling blue waters. This cultural identification has emerged by virtue of their having embraced salsa and its Cuban and Puerto Rican roots, and Caleños proudly acknowledge the role that recordings have played in first introducing and then maintaining these sounds in local popular culture. This is an imagined space built from technological links. Having myself tumbled into an Alice’s Wonderland of sonically induced imaginary landscapes when I discovered Benny Goodman’s 1938 Carnegie Hall recording at the public library when I was twelve—with ensuing metamorphoses via exposure to records of different musical styles ever since—I could easily relate to such a claim. These are worlds Walter Benjamin scarcely dreamed of when describing the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction (1936). Far from being alienated, Caleños have formed a rich and vivid musical culture based on recordings and the memories pulled out of their vinyl grooves.

In the following chapters, I explore the theoretical ramifications of the music-memory link and its conjuncture through sound recordings, unfolding my study through an ethnographic analysis of this process in one Latin American city. I was initially drawn to Cali because of stories I had heard about its being the supposed “world capital of salsa.” During pilot field-work conducted in Caracas in 1992, musicians urged me to visit Cali, especially since the Venezuelan scene had diminished greatly since the mid-1980s. “Cali is the place to be!” they exclaimed—a salsa paradise with dozens of bars and nightclubs specializing in salsa, all-salsa radio stations, and many local bands. Later, I decided to relocate my research to Cali, using Caracas as a point of comparison for my Colombian research.

I conducted fieldwork for this book from November 1994 through June 1996, with follow-up trips in January 1997, December 2000–January 2001, and September 2001. During this time I resided and worked primarily in Cali, but I also made regular trips to towns near the city and out to the Pacific coast port of Buenaventura. I traveled to the Atlantic Coast region on various occasions and had the chance to observe Barranquilla’s Carnival and Cartagena’s Festival de Música del Caribe. I also made regular visits to the capital city of Bogotá and traveled to Medellín, Quibdó, Pasto, and other towns throughout Colombia in order to round out my sense of the country and its diverse geographic, cultural, and musical landscapes. Field trips to Cuba and Ecuador provided important perspectives for considering the projection and reception of salsa in other Latin American cities, under highly diverse historical conditions. The visits to Cuba, in particular, were important for my work in Cali, since Colombians have a strong sense of Cuba as the motherland of salsa music. Colombians who had been able to save money and travel to Cuba often spoke to me with pride about their trips and about the musical wonders they had seen on these pilgrimages.

My research in Cali and other parts of Colombia included intensive documentation of musical venues and salsa performances, as well as interviews with musicians, aficionados, collectors, radio disc jockeys, record producers, dancers, club owners and journalists. I myself needed to learn much about salsa history and its Cuban and Puerto Rican roots, which I compiled through investigation of books, newspapers, magazines, television archives, and conversations with writers and record collectors. I archived local newspaper and magazine articles and collected books written by Colombian authors on salsa and other local popular genres. Thanks to some street vendors who sold salsa records in downtown Cali, I was able to accumulate a large collection of secondhand LPs of Colombian salsa, which I listened to and studied in order to determine components of local musical style.

Although I eventually began participating in the local musical scene as an active musician, my first—and what became predominant—avenue for understanding the mechanisms of Cali’s salsa tradition was to participate in the weekend rumba (partying) that is the hallmark of local popular culture. Social dancing, usually spiked with generous amounts of aguardiente (anise-flavored cane liquor) or rum, is a tremendously important part of Caleño cultural life. Not being much of a drinker or partyer before I arrived in Colombia, I often found the weekend rumba to be exhausting and would complain to my amused friends that the good life was wearing me thin. What those sessions did provide, however, was a view of the immense passion with which Caleños have adopted salsa as their own: head thrown back, arms spread wide, singing loudly and earnestly (if not always in tune) along with the song playing at the moment.

Halfway through my sojourn in Cali, I began to perform as pianist with an all-woman Latin jazz ensemble called Magenta. (The name was chosen by the band’s cofounder Luz Estella Esquivel to characterize the group’s self-identity as integrally female and feminine, but stronger and deeper than the usual feminine color association of rosy pink.) The six-member combo was formed by musicians from various all-woman salsa bands in Cali who were interested in Latin jazz and wanted a break from the diet of commercially oriented salsa tunes they had been playing. Having heard that I could play a bit of jazz piano and hold a salsa piano montuno (groove), I was invited to join them. My musical debut in Cali surprised many of my research informants, who, despite my explaining that I was an ethnomusicologist conducting fieldwork on salsa, usually pegged me somewhere between journalist and hippie. My participation in Magenta Latin Jazz served considerably to establish my acceptance among local musicians and also provided an invaluable tool for understanding the resources and restraints that shape musicians’ lives in this city.

During the course of my research, I came to know people from a wide range of socioeconomic sectors in Colombia. Since salsa was first adopted in Cali by working-class people and is still largely identified with these populist roots, much of my work was with aficionados, fans, and musicians from this sector. My friendships and closest working relationships tended to be with university-educated people from working- and middle-class backgrounds—people with dispositions and values very much like my own. I also spoke with many people from the upper middle class, including both fans and detractors of salsa, which gave me an idea of the complex social and economic discourses cross-cutting popular musical tastes within Cali and in Colombia generally. My core network of friends, however, comprised musicians, aficionados, and record collectors. Ranging in age from our early twenties to our late thirties, most of us were unmarried and only partially employed (most salsa musicians in Cali do not have steady work). So, unhampered by family and work obligations, we spent much time hanging out and listening to music.

For most of my stay in Cali, I shared a flat with Sabina Borja, a Caleña woman my age. Our place soon acquired a reputation as a meeting place and hangout, as friends would drop by at all hours to chat, drink beer or rum, and sample the latest acquisitions of my record collection. For a brief time, the Latin jazz group I played with would meet for rehearsals at our place, and these, too, became a pretext for friends to drop by and hang out, our music serving as a backdrop for the impromptu socializing. Thankfully, the neighbors tolerated our bohemian gatherings and never once complained about the noise, although the music and animated conversation often reached intrusively loud levels. Had I lived in a more affluent neighborhood, this would not have been possible, since these barrios, like their North American and European counterparts, are characterized by a respectful observance of social distance, which includes keeping one’s music at a discreet and unobtrusive level (cf. Pacini Hernández 1995: xxi). Having grown up in a reserved Toronto neighborhood, I witnessed these transformations of our living space with bemusement and wonder (is this really my house?), letting people take charge of putting on the music, prepare drinks, cook, and roam about the flat as they wished. What these gatherings afforded me was a firsthand experience of informal social life in Cali and the role that salsa plays in this context. Over time, as Sabina and I became friends with our neighbors, some of them would come up and join our parties, and this, too, gave me a sense of how everyday life in working- and middle-class Cali both frames and is framed against a lively panorama of musical sound.

During my time in Colombia, I had some of the most intense and exhilarating experiences of my life. I did not grow up with salsa or Cuban music; I became interested in these sounds only in my mid-twenties, when I began studying Latin popular music in Toronto as an aspect of ethnic identity and cross-cultural integration (Waxer 1991). Over the years, however, I have become intensely interested in and involved with the study of salsa and Cuban music, finding this music to somehow embody the diverse and dynamic circumstances of my own life. As a young Canadian woman of mixed Chinese and Jewish ethnic heritage, I have had intense personal experiences of the ways in which diverse cultural flows can shape individual subjectivity. In salsa’s rich and variegated diffusion through the Americas, I have found a metaphorical expression for my own complex background. I believe it was no mistake that I ended up in Cali, a city where, like myself, people have not been among the original creators of a musical style but have nonetheless found meaning in its rhythms, embracing it as their own.

Just as salsa music cannot be performed by one person alone, neither can its study be completed by one sole scholar. It is with sincere gratitude that I thank the many, many individuals who collaborated on various stages of this project. The first tip of the hat goes to my mentor and former doctoral advisor at the University of Illinois, Thomas Turino, who has guided and given feedback on this project since its initial conception as a doctoral thesis. My thanks also to Bruno Nettl, Charles Capwell, Alejandro Lugo, and Norman Whitten, who served on my doctoral defense committees and whose helpful comments on earlier drafts of this material served greatly for its transformation into a book. Special mention also goes to Lawrence Grossberg, whose teachings have strongly influenced my own thinking on popular culture. I would also like to thank Peter Wade, whose trenchant observations during my fieldwork and over the ensuing years have proved enormously helpful in my understanding of Afro-Colombian music and culture within the national context. His book Music, Race, and Nation: Música Tropical in Colombia (2000) has stood as an inspiration and counterpoint to my own work here.

Deborah Pacini Hernández merits special credit as the fairy godmother of this project. Not only did she help with many practical suggestions before I left for the field, but she also provided me with several key contacts in Colombia. Finally, she gave useful feedback on portions of the material and facilitated the links that led to publication of this book with Wesleyan University Press. Thank you for guidance, inspiration and friendship, Debbie. I would also like to thank Gage Averill for providing me with my initial contacts in Cali, which made it possible for me to have commenced this project in the first place. Carlos Ramos and Marta Zambrano provided useful comments and insight when I returned from the field. Dario Euraque and my other colleagues at Trinity College have been of great assistance in helping me refine my notions of race, ethnicity, and diaspora. Wilson Valentín’s use of the concept of surrogation (2002) has been very useful for my work here. Especial thanks to Douglas Johnson for moral support and light. Paul Austerlitz made several invaluable recommendations on earlier versions of this manuscript, and Su Zheng and Frances Aparicio also provided helpful feedback on portions of the work here.

Heliana and Gustavo de Roux were my first hosts in Cali and became my adoptive guardians and mentors while I was in the field. As scholars themselves, their comments, observations, and guidance proved invaluable for my research. Shortly after I began my fieldwork, Jaime Henao and Gary Domínguez became my first key collaborators. Jaime introduced me to several important musicians in Cali and also outlined many musical concepts for me. Gary, the owner of the Taberna Latina, was my main link to the salsotecas and tabernas, in addition to providing key contacts in Cuba; his club became an important place where I met many music lovers. I am indebted to both Jaime and Gary, for without their enormous assistance I could never have realized this project. My deep gratitude also goes to Pablo Solano, who recorded several rare recordings for me to study and whose rooftop listening room is a place to which I always return on my visits to Cali.

This book is woven out of innumerable conversations and interviews with people in Cali and elsewhere in Colombia, not all of whose voices I have been able to include in the account here. Among them are Stellita Domínguez, Kike Escobar, Lalo Borja, Andrés Loiza, Toño Romero, Luisa and Jairo, Baltazar Mejía, Fanny and Jorge Martínez, Jaime and Rochy Camargo, Alejandro and Ruby Ulloa, Henry Manyoma, Rafael Quintero, Richard Yory, Art Owen, Ozman Arias, Gonzalo, Cesar Machado, Lisímaco Paz, Pepe Valderruten, Edgar Hernan Arce, Amparo “Arrebato” Ramos, Evelio Carabalí, Andrés Luedo, Miguel Angel Saldarriaga, Phanor Castillo in Puerto Tejada, Guillermo Rosero, Luis Adalberto Santiago, Fernando Taisechi, Timothy Pratt, Osvaldo González, Diego Pombo, Richard Sandoval, Isidoro Corkidi, Pablo del Valle, Orlando Montenegro, Fabio Arias, Memo Vejerano, Jaime at Zaperoco, Doña Marina de Borja, David Kent, Benjamin Possu, Jorge Mario Restrepo, and Alvaro Bejerano. These people showed great warmth and interest in my project, and it is thanks to their collaboration that I soon felt at home in Cali’s scene. A special tribute goes to Doña Stella Domínguez and Beto Borja, who are no longer with us in body but whose generous laughter and spirit live on.

My conversations with the musicians Luis Carlos Ochoa, Alexis Lozano, Cesar Monge, Wilson and Hermes Manyoma, Enrique “Peregoyo” Urbano, Julian Angulo, “Piper Pimienta” Díaz, Alexis Murillo, Cheo Angulo, Hugo Candelario González, Richie Valdés, Ali “Tarry” Garcés, Felix Shakaito, Santiago Meíja, Alvaro Granobles, John Granda, Hector Aguirre, Nelson González, Gonzalo Palacios, Jon Biafará, Elpidio Caicedo, Jon Granda, Henry, Jorge, Daniel Alfonso, Edgar del Castillo, Fredy Colorado, Jorge Herrera, José Fernando Zuñiga, Carlos Vivas, and others helped to clarify many aspects of the live scene. I am grateful for their willingness to let me sit in on rehearsals and plague them with endless questions. Among the members of all-woman bands, María del Carmen, Francia Elena Barrera, Olga Lucía Rivas, Lizana Mayel, Ana Milena González, Paula Zuleta, Cristina Padilla, and Doris Ojeda offered helpful comments and inspiration. Dorancé Lorza, Chucho Ramírez, and José Aguirre provided valuable information about musical production and arranging. Jairo Varela generously allowed me to observe several recording sessions at Niche Studios, and I had the opportunity to collaborate with him on translating “Solo tú sabes” for his album Prueba de fuego (1997). My conversations with the Puerto Rican musicians Edwin Morales and Ricky Rodríguez of Orquesta Mulenze gave me additional important perspectives on international styles.

Jairo Sánchez generously gave me access to the video archives at Imagenes TV Emilio Larrota cheerfully allowed me to observe recording sessions at Paranova; Carlos Mondragon was helpful at RCN. In Barranquilla, Gilberto and Mireya Marrenco proved to be solid allies; thanks also to Edwin Madera at La Troja. I am grateful to Antonio Escobar for allowing me to participate in the 1995 Festival de Música del Caribe; conversations with Daisanne McLane provided further insight into that event. I would also like to thank Luis Felipe Jaramillo at Discosfuentes in Medellín and Cesar Pagáno in Bogotá, who were generous with both their time and their knowledge.

My trips to Cuba were made especially enjoyable by the friendship and generous assistance of Adriana Orejuela and the Terry family. Conversations with Leonardo Acosta and Helio Orovio provided important information that consolidated my understanding of Cuban music and helped me to better study Cali’s scene. I would also like to give special acknowledgement to Cristóbal Díaz Ayalá, whom I met in Cartagena; he provided materials and important information related to my earlier work on the mambo and Cuban music during the 1940s and 1950s and continues to be a great inspiration and mentor for all of us working in this field.

My special gratitude goes to the following for their solidarity, their time, their insights, and their friendship in the field: Sabina Borja (my unfailing comrade-in-arms), my roommates and fellow doctoral researchers Kiran Ascher and Pablo Leal, the mosqueteros Elcio Viedmann and Kuky Preciado, and Daniel Chavarría and Dennis Pérez. Thanks also to Patricia Galvez; Larry Joseph; Umberto Valverde; Victor Caicedo and family; the Varela family and Catalina Malaver in Bogotá; María Ofelia Arboleda in Medellín; Sugey Moreno in Quibdó; and Cristina and Ramiro Velázquez in Barranquilla. Thanks also to the percussionist Memo Acevedo, my first teacher when I was a fledgling salsiologist in Toronto, who got me started on the long road to Cali and his native Colombia. My gratitude also to Gerardo Rosales, hermano and teacher in Caracas. An especial abrazo to my sisters in Magenta Latin Jazz—Amy Schrift, Luz Estella Esquivel, Dora Tenorio, Sarli Delgado, Alexandra Albán, and Ana Yancy Hoyos. Performing with them was one of the most rewarding experiences of my entire research.

Financial support for this work was provided by generous grants and fellowships from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, the American Association of University Women, the Nellie M. Signor Fund, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, all of which I gratefully acknowledge. I would also like to thank Trinity College in Hartford for institutional support through various phases of this book, and the junior leave that facilitated part of its writing. To the Wenner-Gren Foundation I owe an additional debt of gratitude for the Richard Carley Hunt postdoctoral fellowship that supported completion of this manuscript for publication. Some of the material appearing in this book was published in earlier versions as articles in Latin American Music Review (Colombian salsa; see chapters 4 and 5), Ethnomusicology (all-woman bands; see chapter 5), Popular Music (the viejoteca revival; see chapter 2), the anthology Sound Identities (arrival and impact of recordings in Cali; see chapters 2 and 3), and Situating Salsa (overall history; see introduction and chapters 1–4). I thank the editors of these publications for permission to incorporate revised and expanded renditions of that material here.

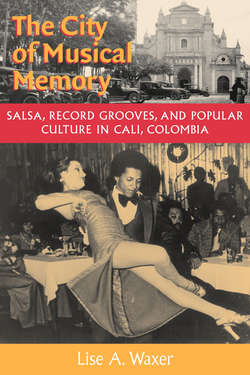

Suzanna Tamminen at Wesleyan University Press has been as wonderful and supportive an editor as one could possibly wish for; I am grateful for her encouragement and feedback. Thanks also to George Lipsitz for his enthusiastic response to the project and his support as series editor. I am also grateful to Thomas Radko at Wesleyan University Press and to Chris Crochetière and Barbara Norton at B. Williams and Associates for their input and support during the publication stage. Pablo Delano assisted with the preparation of some of the photographic illustrations in this volume. I am indebted to Fabio Larrahondo and Jaime González of the newspaper El Occidente in Cali for archival photographs. William Cooley prepared most of the musical notations that appear here, and Steven Russell designed the maps; my thanks to both for their terrific collaboration. All translations from written sources and interviews are my own, as are tables and charts.

Finally, with great pleasure I thank my entire family for their unconditional love through my many years of researching salsa music. Not only did they give me freedom and encouragement to explore this path and travel to Colombia, but they also provided moral support, calls, letters and care packages whenever the going got tough. I am also indebted to the Arias-Satizábal family for their love and support through this project. An especial vote of gratitude and love goes to my husband and research collaborator, Medardo Arias Satizábal. He provided important contacts during the final stages of fieldwork and follow-up and offered several observations and perspectives of his own. His magnificent support and understanding during these months of writing have been without equal. Gracias, amor lindo.