Читать книгу WITH JUSTICE FOR SOME - Lise Pearlman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

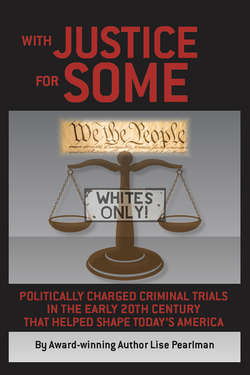

4. SHOWDOWN WITH THE SUPREME COURT The Lynching That Gave Teeth to the Fourteenth Amendment Right to a Fair Trial

Оглавление“To Justice Harlan. Come get your nigger now.”

– NOTE PINNED TO ED JOHNSON’S CORPSE1

During Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency, novelist and playwright Thomas Dixon was the nation’s most popular lecturer. In the age before radio, Dixon spoke to sold-out audiences across the country, waxing poetic on racial purity, the evils of Socialism and the proper role of women – at home raising children. Belittling bi-racial intellectuals like Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois, Dixon repeatedly warned his audiences that Negroes were a race of savages: “[No] amount of education of any kind, industrial, classical or religious, can make a Negro a white man or bridge the chasm of centuries which separate him from the white man in the evolution of human nature.”2 (Dixon’s anger may have been fueled by abhorrence of his own half-brother, the son of Dixon’s father and the family cook.)3

The national fad since the late 19th century was to gather round the piano and sing “coon” songs. The public could not get enough of comic sheet music that portrayed Negro men as loose-living, watermelon-eating, ignorant buffoons; ridiculed them as lazy, shiftless gamblers and hustlers or drunks, or demonized them as razor-wielding street bullies. White women singers in black face gained followings as “coon shouters.” Hundreds more coon songs fed an insatiable public appetite that lasted through the turn of the century. Historian Eric Foner notes, “By the early 20th century [racism] had become more deeply embedded in the nation’s culture and politics than at any time since the beginning of the antislavery crusade and perhaps in our nation’s entire history.”4

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Dixon_Jr.

During Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency, novelist and playwright Thomas Dixon was the nation’s most popular lecturer. In the age before radio, Dixon spoke to sold-out audiences across the country, waxing poetic on racial purity, the evils of Socialism, and the proper role of women -- at home raising children. Dixon repeatedly warned his audiences that Negroes were a race of savages: “[No] amount of education of any kind, industrial, classical or religious, can make a Negro a white man or bridge the chasm of centuries which separate him from the white man in the evolution of human nature.” Dixon’s anger may have been fueled by abhorrence of his own half-brother, the son of Dixon’s father and the family cook.

Source of book cover and movie poster: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Clansman: A_Historical_Romance_of_the_Ku_Klux_Klan

Dixon published The Clansman in 1906 in homage to the Ku Klux Clan; it became the basis for the nation’s first blockbuster movie in 1915, The Birth of a Nation.

In 1905, one out of six American households bought the sheet music for “If the Man in the Moon Were a Coon.”5 That same year Dixon published the best seller The Clansman. A decade later it would be turned into the blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation. In a key scene, Dixon reenacted the most frightening moment of his childhood. A Confederate widow got his father and his uncle, who headed the local Klan, to don their white robes and hoods and join other Klansmen in stringing up a former slave accused of attacking the woman’s daughter. The Ku Klux Klan hanged the man in the center of town and shot him repeatedly for good measure. Dixon’s mother reassured her young son, “They’re our people – they’re guarding us from harm.”6

Among those who enjoyed putting on black face to ridicule former slaves were members of the white supremacist Pickwick Club, who paraded annually at Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Since 1874, many of their members also belonged to the Louisiana White League, formed by Confederate Army veterans to oppose Reconstruction by acts of violence and intimidation. The White League was similar to the secretive KKK, but had enough local support to operate openly without hoods. Members of the Pickwick Club and White League joined with other Democrats in passing Louisiana’s 1890 Separate Train Act, which required railroad companies to isolate African-American travelers. Eighteen local black activists reacted by forming a Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law. The test case they set in motion would have enormous repercussions for more than half a century.

The New Orleans citizens’ committee asked a volunteer named Homer Plessy, who was one-eighth black, to buy a first-class ticket to ride in a car designated “whites only.” The committee prearranged with the railroad’s management to have Plessy arrested for civil disobedience when he declined to move out of that car. The citizens’ committee then paid for Plessy’s legal challenge of the $25 fine, expecting vindication in the Supreme Court. After all, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution plainly declared that “no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States . . . nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Source of sheet music photos: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coon_song

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18826048

Sales of sheet music for “Coon Songs” soared nationwide in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “Coon, Coon, Coon” was advertised as the most successful song of 1901. (A “honey gal” lived with her man in unmarried sin.) Lower right: Irving Berlin as a young immigrant composer – the man who became one of America’s greatest songwriters was among many who wrote popular “Coon Songs” for public consumption.

To the civil rights committee’s shock, the high court decided Plessy v. Ferguson seven-to-one against them. The panel of jurists that rejected the claim that the Separate Car Act violated the Fourteenth Amendment included a proud member of the Pickwick Club Mardi Gras Krewe and of the militant White League who had been raised on a slave-owning plantation. Louisiana Justice Edward D. White joined six other justices who put the blessing of the highest court in the land behind enforced segregation of mixed-blood or Negro citizens so long as the accommodations were called “equal.” Covered by that fig leaf, discriminatory Jim Crow laws proliferated in the South and emboldened physical abuse of blacks throughout the land.

In 1905, Chattanooga, Tennessee, maintained a significantly better civil rights record than most other Southern cities. The industrial city of 60,000 included many transplanted Northerners as well as a substantial middle class among its 20,000 black residents. The city had not held a lynching since 1896 – the same year the Supreme Court of the United States decided the landmark case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Back in 1887, Chattanooga had elected a black lawyer, Styles Hutchins, to represent the district for one term in the state legislature. Progressive religious leaders fought bigotry and lobbied for peaceful resolution of all conflicts.

As of 1905, publisher Adolph Ochs still owned the Chattanooga Times, though the Jewish philanthropist had already moved to Manhattan to oversee his more recent acquisition, the New York Times. Despite the city’s progress, fifteen percent of Chattanooga’s adults couldn’t read. A large number of whites held dead-end, menial jobs and increasingly resented the growing prosperity of the city’s black professionals. In Tennessee, new Jim Crow laws made race hatred far more contagious. It went viral in Chattanooga that winter.

Since early December of 1905, the papers had been reporting a wave of burglaries, rapes and robberies by Negro men, including a girl attacked in her own bed in an orphanage and another on a downtown street. On Christmas Eve tension rose dramatically when a notorious black gambler, Floyd Westfield, barricaded himself in his house with a gun when a white constable headed a posse sent to arrest Westfield for disturbing the peace in his neighborhood by shooting off fireworks. When the constable and his men broke the door down, Westfield fired, killing the constable. The day after Christmas, Ochs’ often Progressive Chattanooga Times captured the widespread fear: “Desperadoes Run Rampant in Chattanooga; Negro Thugs Reach Climax of Boldness.” The paper blamed the climate of fear partly on the sheriff for not being tough enough. A month later, vigilantes impatiently waited for Westfield’s murder trial to reach its foregone conclusion. Given their druthers, they would have already strung the gambler up to send the Negro community a strong message about respect for law and order.

When locals heard what happened after dark on Tuesday evening, January 23, 1906, to twenty-one-year-old Nevada Taylor, all many could think about was vengeance. Someone jumped the popular office worker from behind and brutally raped her as she approached the cemetery gate near her home in the city’s St. Elmo District. The pretty blonde still lived with her widowed father, a groundskeeper at the Forest Hills Cemetery, and commuted daily by trolley to her job downtown. Whoever had assaulted her shortly after 6:30 p.m. had almost choked her with a leather strap around her throat and left her unconscious.

Hamilton County Sheriff Joseph Shipp jumped on the case Tuesday evening as soon as Nevada’s father contacted him. The sixty-one-year-old diehard Rebel was tall and thin with receding white hair, moustache and goatee. Though he only had a seventh grade education, since his arrival in Chattanooga from his home state of Georgia, the Civil War veteran had done quite well for himself in a furniture business and through real estate investments. After he and his wife raised their seven children, Shipp decided to run for sheriff. The Confederate veteran had all the qualities of a lawman the county’s white male voters could trust – a hard-drinking, cigar-chomping, poker-playing champion of Southern womanhood.

Shipp’s bloodhounds sniffed the scent from Nevada’s torn dress and quickly found the abandoned black leather strap. City newspapers featured the shocking details on Wednesday together with a $50 reward, almost two months’ wages for many workers. By day’s end, the reward would grow to $375, a sum larger than many residents earned annually. Nevada had told the sheriff that she did not get a good look at the man who grabbed her from behind and threw her over the fence as she cried out for help. But she heard his oddly gentle voice. At first, she could not specify his race, but said he was dressed in black, wore a hat, was athletic and shorter than average. He might have been five-foot six.

After talking with the sheriff, Nevada became convinced her attacker was Negro. Under the law, that made the rape a capital crime, which it was not if committed by a white man. Sheriff Shipp was up for reelection to a second two-year term at the end of March. He realized that if he identified the rapist quickly, he could get the suspect tried, convicted and executed well before the election. In a newspaper interview on Wednesday, the sheriff made a solemn promise to his constituents: “I know the people thirst for judgment of the Negro who did this. I can assure the people that all at the courthouse agree and will be satisfied with nothing less. I am confident we will find this beast and he will feel the vengeance of our community upon him.”7

What underlay that desire for vengeance was white Chattanoogans’ underlying terror once again being exploited by newspapers and political candidates – as it had been cultivated among white Americans generally from colonial days by preachers, civic leaders and journalists.8 Despite his boast, Shipp knew he could be thrown out of office if he did not quickly solve the sensational crime that had the city of Chattanooga in an uproar. That same day, the sheriff and his deputies arrested a twenty-five-year-old grocery deliveryman, James Broaden, who worked in the area and fit the general description of Nevada’s assailant. Sheriff Shipp subjected Broaden to tough questioning, but kept the investigation open. The next morning, the sheriff was home eating breakfast when he received a call from a man named Will Hixson who worked near the cemetery. Hixson’s first question was whether the reward was still available. When told it was, Hixson met with the sheriff and described a black man he claimed to have seen at the St. Elmo trolley stop ten minutes to six on Tuesday evening “twirling a leather strap around his finger.”9

Tuesday evening had been particularly dark and gloomy, but Hixson said he had offered the same man a light on Monday and believed he could identify the stranger if he saw him again. Late Thursday morning, Hixson called the sheriff to say he spotted the man and learned his name, Ed Johnson. Shipp rushed over to the run-down colored neighborhood on Chattanooga’s south side to the shack on Higley Row occupied by Skinbone Johnson and his wife. Their twenty-four-year-old son Ed was not there. The sheriff ransacked his parents’ home and that of Johnson’s sister who lived nearby, but found no evidence relating to the crime. Shipp had no warrant. Under state law, he didn’t need one.

On a hunch, the sheriff hid around the corner and followed Johnson’s sister a few minutes later. She flagged down her brother as he rode on the back of an ice wagon. Sheriff Shipp pounced. He had his deputies handcuff Johnson and take him to the county jail for questioning. Johnson asked the sheriff, “Why are you doing this?” but got no response.10 At the jailhouse, the sheriff followed his usual methods. He tried to beat a confession out of Johnson.

Like many other colored kids, Ed Johnson had left school in the fourth grade. The police never read him his rights and he was not yet offered an attorney – suspects would receive neither immediate protection for decades. Yet Johnson steadfastly maintained his innocence and gave the sheriff a sizeable list of alibi witnesses who had seen him working at the Last Chance Saloon – miles away from the crime – from late Tuesday afternoon through ten o’clock that night. The sheriff did not believe him. Shipp called the District Attorney. The two interrupted a trial then being conducted by criminal court Judge Samuel McReynolds to alert him that they had the rapist in custody. Word quickly spread.

Fearing that a lynch mob might assemble, the sheriff and judge decided to transfer Johnson to Knoxville temporarily. The jail had already been besieged twice before. Sure enough, that night, 1,500 men – many wielding guns and ropes, bricks and rocks – descended on the Chattanooga jailhouse demanding “the Negro.” They cut the telephone wires to prevent calls for reinforcements and shut off power. Refusing to believe Johnson had been transferred elsewhere, they stormed the building, smashed all the windows and used a battering ram to try to break down the front door. Though police responded, they could not disperse the huge, angry crowd. Then Judge McReynolds showed up and called the governor to ask for National Guard reinforcements. The angry crowd stayed put. One man asked the judge, “Going to help us hang that Negro?” Another said, “The jury is in and we find him guilty and sentence him to hang by the neck until dead.”11

McReynolds told them to go home, but did nothing to try to blunt their anger against a man who had not even been formally accused, let alone had his day in court. Instead, the former prosecutor explained, “We have laws we must follow.” He then pledged that he would give the case the highest priority and told them, “I hope that before week’s end, the rapist will be convicted, under sentence of death and executed according to law before the setting of Saturday’s sun.”12 Such betrayal of bias should have forced McReynolds off the upcoming trial. Just over a decade earlier, the United States Supreme Court had traced back through Ancient Rome and Athenian Greece to the Old Testament the basic guarantee a free society promises all criminal defendants: the presumption of innocence.13

Not until Saturday did Sheriff Shipp bring Nevada Taylor to Nashville to view the two suspects then in custody: Broaden and Johnson. Shipp instructed them to speak so she could try to identify her assailant. Sheriff Shipp needed Nevada Taylor to pick the same man as Hixson. He was worried about more than the upcoming election; he was also concerned about his own safety and that of his staff, other prisoners and the jailhouse itself. When Johnson’s voice sounded to Nevada different from that of the rapist, Shipp assumed that the prisoner was just trying to disguise it. Soon Nevada told the sheriff what he wanted to hear – that Johnson was “like the man as I remember him.” He “has the same soft, kind voice.”14 The sheriff immediately dispatched a wire to the prosecutor in Chattanooga. An all-white male grand jury indicted Johnson that afternoon, after which Judge McReynolds met with the sheriff and prosecutor to plan their joint trial strategy, which nowadays would be unethical but was then routine.

Tennessee was more advanced than many states in requiring trial judges to appoint a defense lawyer in all death penalty cases. But that was often an illusory right since the judge had discretion to choose any lawyer in his jurisdiction, even if the lawyer was clearly not up to the task. The trio thought about appointing a black defense lawyer, but decided that if Johnson somehow won acquittal, the mob would likely take revenge on the judge as well as defense counsel. McReynolds instead selected Robert Cameron, a known lightweight in the local bar who mostly earned his money finding cases for other lawyers. Cameron had no criminal law experience and no contested civil trials under his belt.

On Saturday evening, January 27, former Circuit Judge Lewis Shepherd stopped by Judge McReynolds’ home to offer his suggestions for the high-profile case. Thirty-four-year-old McReynolds had only been on the bench three years, but was highly ambitious and pragmatic. He was open to ideas from the balding liberal, who at fifty was one of the leading lawyers in the state and a seasoned state politician as well. Shepherd was then defending gambler Floyd Westfield on the charge of murdering the constable. McReynolds surprised Shepherd by asking him to partner with Cameron as Johnson’s lead counsel. Shepherd accepted on the condition that McReynolds would also name a prominent civil trial lawyer to serve as well.

The next morning before church, McReynolds summoned both Cameron and civil lawyer W. G. Thomas to his chambers. Thomas begged to be passed over, but McReynolds would not take no for an answer. McReynolds dumbfounded the pair by telling them he would not give them time to learn the facts and applicable law. The trial would start as soon as the Westfield trial ended, perhaps by the end of the week, when Judge Shepherd could join their team. As they left, Judge McReynolds reminded them they would not get paid, hinting broadly he expected little effort. Neighbors and clients immediately shunned both Thomas and Cameron and subjected them to ridicule. Thomas’s secretary quit. Then rock-throwing hooligans attacked the home Thomas shared with his mother. Though Thomas moved her to a relative’s for safety, she and Cameron’s wife begged the two men to get off the case.

Johnson meanwhile stayed in the Nashville prison where he had been transferred for safe-keeping. On February 2, he gave a jailhouse interview to the Nashville Banner in which he protested his innocence and repeated the alibi he had told the sheriff. Johnson did not meet his lawyers until the following day when Shepherd and Thomas got him to review with them in detail his movements on January 23. Shepherd told Johnson how grim the situation looked because “the people of Chattanooga are very mad and they want someone to die for this crime.”15

Johnson must have melted their hearts with his reply: “But I don’t understand. I never done what they say. I swear to God I didn’t. I’ve never seen the woman they brought up here before. I didn’t even know where she lived. I just want to go home.”16 Shepherd embraced his client.

All three lawyers quickly scrambled to gather alibi evidence. Judge McReynolds had already held an improper private meeting with two of the three defense lawyers, the sheriff, the mayor of Chattanooga and District Attorney Matt Whittaker. Like the sheriff, Whittaker was on the upcoming ballot for reelection and under similar pressure to convict Johnson and make him hang for the rape of Nevada Taylor. McReynolds warned the defense team against making a motion for change of venue or asking for a postponement of the trial to allow the community to calm down. Contrary to his duty to decide how Johnson’s case would proceed based on the arguments about to be presented in court, McReynolds had made up his mind in advance not to grant either form of relief for fear that it would only infuriate the mob and precipitate a lynching. McReynolds had already indicated to the sheriff and prosecutor that Johnson’s acquittal would present the same serious political problem. The judge felt Johnson’s life well worth sacrificing to preserve the façade of a law-abiding society. Let the defense lawyers try their best in an impossible time frame, the script was already written – Johnson had to die to satisfy the mob.

Shepherd was determined to succeed against all odds. For assistance, he had already approached the most gifted local African-American attorney for help, Noah Parden, the younger partner of black politician Styles Hutchins. Unlike Hutchins, forty-one-year-old Parden was scholarly and athletic. He had light skin, tight curly hair, a long straight nose and a bushy mustache. Parden had been raised in an orphanage since the age of six when his mother, a housecleaner, died of illness. He never knew his father, who likely was white.

Among the few possessions Parden’s mother had left him was a Bible, perhaps explaining why he embraced his legal career like a religious calling. Like Hutchins, Parden was an impassioned champion of individual rights, but unlike his mentor, he was far more pragmatic. He did not dare offer help to Johnson publicly for fear of retribution from both the white and black communities, both of which wanted the alleged rapist quickly brought to justice and the whole ugly matter put behind them. Yet Parden helped Johnson’s lawyers track down alibi witnesses and gave valuable behind-the-scenes advice. Thomas and Cameron worked day and night establishing that Johnson was at the saloon when he said he was from 4 p.m. until 10 p.m. the night of the rape. Yet they recognized that the bar’s regulars were considered low-life with little credibility.

The lawyers could do nothing with Parden’s other lead. Two black residents in the neighborhood of the assault had told Parden that they had seen a white man washing off blackface on the street about 7 p.m. that fateful night. Burnt cork and greasepaint were then commonly used by whites in minstrel shows, and it would have been a smart move for a white rapist on a dark night to wear such makeup to reduce the chances of being caught. But the two potential defense witnesses realized the sheriff would never believe them; they refused to come forward.

The tabloids meanwhile kept the ire of impatient community avengers at fever pitch awaiting the trial’s start. As a precaution, heavily armed guards brought Johnson back from Nashville in secrecy to the Chattanooga jail. When proceedings began on Tuesday morning, February 6, Judge McReynolds filled the courtroom with lawyers and newsmen strongly favoring the prosecutor; he refused admittance to Ed Johnson’s parents and his pastor. McReynolds designated an all-white list of names for the jury panel, though such skewed practice was illegal. Two men who had qualms about the death penalty were dismissed. The defense excused others who admitted that they already believed Johnson guilty. When addressing the jury panel, Shepherd stood next to his slump-shouldered client and told them, “I ask but one thing of you. I ask that you treat this man throughout this trial and during your deliberations as you would a white man. He deserves no less. The law requires no less.”17

During the three-day trial, the whole gallery openly cheered District Attorney Matt Whittaker and razzed the defense team at will without any reprimand from the judge. Johnson remained listless as both Hixson and Taylor identified him. Sheriff Shipp and his deputies testified that Johnson had told three inconsistent versions of his alibi when they were grilling him at the jail. It was almost dark when Johnson took the stand on his own behalf, but he suddenly perked up and explained to the jury his whole day Tuesday, January 23, in animated detail. Johnson reeled off the names of nine witnesses who saw him at the saloon. The judge kept the trial going late that night and reconvened early the next morning for another full day.

Aside from the alibi witnesses, the most compelling defense witness was an elderly black building supervisor of a nearby white church. His name was Harvey McConnell. McConnell accused Hixson of framing Johnson for the reward money. He testified that on Wednesday, January 24 – the day after the rape – Hixson approached him to ask for a physical description of the roofer Hixson had seen recently working at the church and for the roofer’s name.

The defense argued that it was not based on Hixson’s own observations Tuesday night but McConnell’s description of Johnson that Hixson then went to the sheriff to collect his reward. Other defense witnesses testified that it was so dark Tuesday night before six p.m. that a pedestrian could not identify the race of a passerby at five feet, let alone the features of the stranger Hixson had claimed to have seen twirling a leather strap Tuesday night. Hixson took the stand and denied ever speaking to McConnell and reaffirmed his identification of Johnson.

On Thursday, Nevada Taylor retook the stand but was less sure now then she had been before: “I will not swear that he is the man, but I believe he is the Negro who assaulted me.”18 A juror then yelled, “If I could get at him, I’d tear his heart out right now.”19 Shepherd demanded a mistrial, which should have been declared, but Judge McReynolds had no such intention. After three hours of impassioned oral argument on both sides, it was after 5 p.m. when Judge McReynolds instructed the jury and nearly six when he ordered them to begin immediate deliberations.

It was almost midnight when the exhausted jury came back to the courtroom. Much to the judge and sheriff’s shock, the jury announced a deadlock. Even under intense pressure from the prosecutor to “send that black brute to the gallows,” four jurors held out for acquittal. McReynolds ordered them to get some rest and return Friday morning. What happened next would only come out in a later federal investigation. “Long after everyone else had left the courthouse, McReynolds, prosecutor Whittaker, and Sheriff Shipp shared a bottle of whiskey in the judge’s chambers. They all agreed that a ‘not guilty’ verdict could not be tolerated, nor could a mistrial – the city could not afford, financially or socially, a second trial.”20 How they followed up on that conspiratorial session never came to light.

Within an hour of when the jurors arrived Friday morning, they surprisingly announced they had reached agreement. Guards brought Ed Johnson into court handcuffed and in leg irons as a crowd quickly gathered to hear the jury verdict of guilty. Death was mandatory since the jury included no recommendation of leniency. Shepherd announced he would seek a new trial the next day, but his co-counsel Thomas disagreed and asked McReynolds to appoint three more attorneys to help resolve the defense team’s impasse on what to do next.

McReynolds then met again with District Attorney Whittaker – yet another breach of the judge’s required neutrality – and let the prosecutor name two of the three defense consultants. Not surprisingly, the new lawyers joined forces with Thomas to try to pressure Shepherd and Cameron to forego requesting a new trial or appeal even though both men were convinced that the four jurors who changed their minds so quickly had been tampered with. The advisors told the defense team they had now completed all of their ethical responsibilities to Johnson and any further legal action would simply cause a few months’ delay of the inevitable hanging. Thomas feared worse: that any further defense of Johnson’s innocence might just incite the lynch mob to kill all of them and the sheriff would no longer get in the mob’s way.

By the time the attorneys conferred with Ed Johnson in the jail Friday afternoon, they convinced the poor man he had only two choices, both ugly: to forego any further proceedings and die with relative dignity at the hands of the county hangman or to assert his rights and be lynched and mutilated by a rabid mob. With Shepherd now grudgingly silenced, Thomas talked Johnson into waiving his rights and throwing himself on the court’s mercy. McReynolds showed none. He praised the jury as among the finest he had ever observed and announced his personal endorsement of their verdict that the defendant was the guilty party. McReynolds sentenced Johnson to be hanged on March 13 – fulfilling his pretrial promise.

On Saturday, February 10, Skinbone Johnson arrived at Hutchins’ and Parden’s law firm desperate for help. He told Parden that his son did not want to die for a crime he had not committed and had only waived his appeal under duress. Styles Hutchins overheard their conversation and convinced Parden this was an historic occasion that cried out for their help. Money was not an issue; the two were used to poor black clients not being able to repay them with anything but gratitude and a home-cooked meal. Parden already believed Johnson was innocent and the trial a mockery of justice. He came to Shepherd’s home on Sunday and enlisted the remorseful older lawyer’s aid.

Ed Johnson’s chances of regaining his freedom were slim to none in the Tennessee Supreme Court and not much better under federal law. The Bill of Rights guaranteed the right to trial by jury and the right not to be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law, but those constitutional rights had been interpreted to apply only in federal courts. After the Civil War, the country enacted the Fourteenth Amendment declaring that “no state” shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” But the Supreme Court had not yet determined whether that controversial Amendment was intended to enforce the Bill of Rights in state criminal trials.

The next five weeks would involve a race against the hangman’s noose through four courts, including the highest in the land. On Monday morning, Parden and Hutchins surprised Judge McReynolds with a hastily prepared motion for a new trial. The judge told them to come back on Tuesday when the prosecutor would be available. The next morning Judge McReynolds denied the motion for a new trial as untimely, telling Parden that the three-day deadline had actually run on Monday. When Parden then requested a certified record to permit review by the Tennessee Supreme Court, McReynolds sneaked off on a week’s unplanned vacation to stymie that process. Parden persisted anyway.

On March 3, the Tennessee Supreme Court unanimously rejected the plea to delay Ed Johnson’s execution. Four days later, Parden raced to the federal district court in Knoxville to challenge the trial. He cited a United States Supreme Court case on Sixth Amendment guarantees for a fair trial and pointed out the skewed handling of seventeen rape cases in the county over the past six years. Most of the victims were black, but only two of those cases resulted in convictions and the rapists got short jail terms. Three victims were white women who accused black men. All three of those cases resulted in convictions, with two of the three men sentenced to death.

By coincidence, Sheriff Shipp was on the same three-hour train to Knoxville as Parden, but traveling in first class the sheriff never saw the Chattanooga lawyer in the “coloreds” car. Shipp was planning to transfer Johnson back to Chattanooga, where he would likely be at the mercy of another lynch mob. Not in any particular hurry, Shipp ran other errands and spent time with old friends before he reached the prison. By the time he arrived, Shipp was shocked to find a marshal with an order signed by Judge Clark keeping Johnson in Knoxville pending a hearing on March 10.

Shipp brought the judge and prosecutor to the unprecedented hearing, which lasted into the night. At lunch-time on March 11, Judge Clark issued his ruling on the merits of Parden’s petition. The judge did not grant the requested relief, but issued a ten-day stay of Johnson’s execution to allow for United States Supreme Court review. The Chattanooga officials immediately questioned Judge Clark’s authority to change the execution date. Judge McReynolds suggested they might disregard the federal judge’s ruling and go ahead with the execution on its prior schedule. Instead, the group asked Tennessee’s Governor William Cox to intercede. He postponed Johnson’s execution just one week, to March 20.