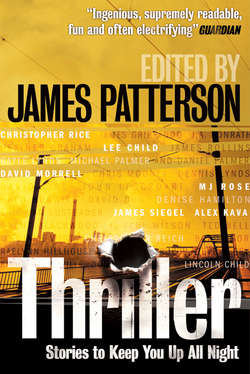

Читать книгу Thriller: Stories To Keep You Up All Night - Литагент HarperCollins USD, Ю. Д. Земенков, Koostaja: Ajakiri New Scientist - Страница 13

Empathy

ОглавлениеI sit in a dark motel room.

It’s pitch-black outside, but I’ve pulled the shades down tight anyway, so she won’t see me when she walks in. So she’ll be sure to turn away from me to switch on the light.

I don’t like the dark.

I live on Scotch and Ambien so I never have to stare at it, because sooner or later it becomes the dark of the confessional and I’m eight years old again. I can smell the garlic on his breath and hear the rustle of his clothing. For a moment, I’m a shy, sweet-natured, baseball-crazy boy again, and I physically shrink away from what’s coming.

Then everything turns red and the world’s on fire.

I look back in anger, because anger is what I’ve become—a fist of a man.

Anger is what cost me my home, and anger is what put me into court-ordered therapy, and anger is what finally kicked me off the LAPD and into hotel security, where I can be angry without killing anyone.

Not yet.

You’ve heard of the hotel I work in. It’s considered top-shelf and is patronized by various Hollywood wannabes and occasional bona fide celebrities. As downward spirals go, mine hasn’t sucked me to the bottom yet, only to Beverly and Doheny.

I get to wear a suit and earpiece, something like a Secret Service man. I get to stand around and look semi-important and even give orders to the hotel employees who don’t get to wear suits.

She was a masseuse in the hotel spa.

Kelly.

She was known for her deep-tissue and hot stone. I first talked to her in the basement alcove where I went to be alone—but I’d noticed her before that. I’d heard the music seeping out of her room on my way to the back elevators, and when she entered the basement to grab a smoke, I complimented her on her taste. Most of the hotel masseuses were partial to Enya, to Eastern sitar or the monotonous sound of waves lapping sand. Not her. She played the Joneses—Rickie Lee and Nora and Quincy, too, on occasion.

“Do your customers like it?” I asked her.

She shrugged. “I don’t know. Most of them are just trying to not get a hard-on.”

“Occupational hazard, I guess?”

“Oh, yeah.”

She was pretty, certainly. But there was something else, a palpable aura that made it feel humid even in full-blast air-conditioning.

I believe she noticed the ugly swelling on the knuckles of my right hand, and the place in the wall where I’d dented it.

“Bad day?”

“No. Pretty ordinary.”

She reached out and touched my face, fanning her fingers across my right cheek. Which is more or less when she told me she was an empath.

I won’t lie and tell you that I knew what an empath was.

A look had come over her when she touched my face—as if she’d felt that part of me which I rarely touch myself, and then only in the dark before the Johnny Walker has worked its magic.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“For what?”

“For whatever did this to you.”

This is what an empath can do—their special gift. Or curse, depending on the day.

I learned all about empaths from her over the next few weeks. As we talked in the basement, or bumped into each other on the way into the hotel, or grabbed smokes outside on the corner.

Empaths touch and know. They feel skin and bone but they touch soul. They see through their hands. Everything—the good, the bad and the truly ugly.

She saw more ugly than she wanted to.

The ugliness had begun to get to her, to send her into a very dark place.

It was one of her customers, she explained.

“Mostly I just see emotions,” she confided, “you know, happiness, sadness, fear—longing—all that. But sometimes…sometimes I see more…I know who they are, understand?”

“No. Not really.”

“This guy—he’s a regular. The first time I touched him, I had to pull my hands away. It was that strong.”

“What?”

“The sense of evil. Like touching—I don’t know…a black hole.”

“What kind of evil are we talking about?”

“The worst.”

Later, she told me more. We were sitting in a bar on Sunset having drinks. Our first date, I guess.

“He hurts kids,” she said.

I felt that special nausea. The kind that used to subsume me back in the confessional, when he would come for me, that dark wraith of hurt. The nausea that came when my little brother dutifully followed me into altar-boyhood and I kept my mouth zipped tight like a secret pocket. Don’t tell…don’t tell. There’s a price for not telling. It was paid years later, on the afternoon I found my sweet, sad brother hanging from a belt in our childhood bedroom. Over his teenage years, he’d furiously sought solace in various narcotics, but they could only do so much.

“How do you know?” I asked Kelly.

“I know. He’s going to do something. He’s done it before.”

When I told her she might want to report him to the police, she shot me the look you give to intellectually challenged children.

“Tell them I’m an empath? That I feel one of my clients is a pedophile? That’ll go over well.”

She was right, of course. They’d laugh her out of the station.

It was maybe a week later, after this customer had come and gone from his regular appointment and Kelly was looking particularly miserable, that I volunteered to keep an eye on him.

“How?”

We were lying in my bed, having taken our relationship to the next level as they say, both of us using sex as a kind of opiate, I think—a way to forget things.

“His next appointment?” I asked her. “When is it?”

“Tuesday at two.”

“Okay, then.”

I waited outside the pool area where the clients saunter out looking sleepy and satiated. He looked frazzled and anxious. She’d slipped out of the room while he undressed to tell me what he was wearing that day. She needn’t have bothered—I would’ve known him anyway.

He carried his burden like a heavy bag.

When he got into the Volvo brought out from the hotel-parking garage, I was already waiting in my car.

I followed him onto the 101, then into the valley. We exited onto a wide boulevard and stayed on it for about five miles, finally making a turn at the School Crossing sign.

He parked by the playground and sat there in his car.

It came back.

The paralytic sickness that made me want to crawl into a ball.

I stayed in the front seat and watched as he exited the car and sidled up to the fence. As he took his glasses off and wiped them on the pocket of his pants. As he scoped out the crowd of elementary-school kids flowing out the front gate. As his attention seemed to fixate on one particular boy—a fourth-grader maybe, a sweet-looking kid who reminded me of someone. As he began to follow this boy down the street, edging closer and closer the way lions separate calves from the herd. I watched and felt every bit as powerless and inert as I did back when my brother bounded down the steps of our house on the way to his first communion.

I couldn’t move.

He stepped up behind the boy and began conversing with him. I didn’t have to see the boy’s face to know what it looked like. The man reached out and grabbed the boy by the arm and I still sat there in the front seat of my car.

It was only when the boy broke away, when he turned and ran, when the man took a few halting steps toward him and then slumped, gave up—that I actually moved.

Anger was my enemy. Anger was my long-lost friend. It came in one red-hot surge, sending the sickness scurrying away in terror, propelling me out of the car, ready to finally protect him.

Joseph, I whispered.

My brother’s name.

The man slipped back into his car and drove away. I stood there with my heart colliding against my ribs.

That night, I told Kelly what I was going to do.

We lay in bed covered in sweat, and I told her that I needed to do this. The anger had come back and claimed me, wrapped me in its comforting bosom and said, You’re home.

I waited at the school the next afternoon, and the one after that. I waited all week.

He came the next Monday—parking his Volvo directly across from the playground.

When he got out, I was standing there to ask him if he could point me toward Fourth Street. When he turned and motioned over there, I placed the gun up against his back.

“If you make a sound, you’re dead.”

He promptly wilted. He mumbled something about just taking his money, and I told him to shut up.

He entered my car as docile as a lamb.

A mother stared at us as we drove away.

I went to a place in the valley that I’d used before, when the redness came and made me do certain things to suspects with big mouths and awful résumés. Things that got me tossed off the force and into mandated anger management where the class applauded when I said I’d learned to count to ten and avoid my triggers. Triggers were the things that set me off—there was an entire canon of them.

Men in collar and vestment. That was trigger number one.

We had to walk over a quarter of a mile to the sandpit. They’d turned it into a dumping ground filled with water the color of mud.

“Why?” he said to me when I made him stand there at the lip of the pit.

Because when I was eight years old, I was turned inside out. Because I killed my brother as surely as if I’d tied that belt around his neck and kicked away the chair. That’s why.

His body flew into the subterranean tangle of junk and disappeared.

Because you deserve it.

When I showed up at work the next day, she wasn’t there. I wanted to let her know; I wanted to ease her burden. When I called her cell—she didn’t answer.

I asked hotel personnel for her address—we’d always slept at my place because she had a roommate. Two days later I went to her second-floor flat in Ventura and knocked on the door.

No answer.

I found the landlord puttering around the backyard, mostly crabgrass, dandelions and dirt.

“Have you seen Kelly?” I asked him.

“She’s gone,” he said without really looking up.

“Gone? Gone where? Gone to the store?”

“No. Gone. Not here anymore.”

“What are you talking about? Where’d she go?”

He shrugged. “She didn’t leave an address. Her and the kid just left.”

“What kid?”

He finally looked up.

“Her kid. Her son. Who are you, exactly?”

“A friend.”

“Okay, Kelly’s friend. She took the kid and left. That lowlife of a boyfriend picked them up. End of story.”

I will tell you that I still did not understand what happened.

I will tell you that I went back to the hotel and calmly contemplated the situation. That when another masseuse walked out of her room—Trudy, one of the girls Kelly used to talk to—I said tell me about Kelly. She’s an empath, I said.

“A what?”

“An empath. She touches people and knows things about them.”

“Yeah. That they’re horny and out of shape.”

“She knows what they’re feeling—what kind of people they are.”

“Ha. Who told you that? Kelly?”

I still didn’t understand.

Even with Trudy staring at me as if I’d arrived from a distant galaxy. Even then, I refused to grasp what was right there.

“Kelly has a son,” I said.

“Uh-huh. Nice kid, too. No thanks to her. Okay, that’s not fair. She just needs to develop better taste in men.”

“You mean the father?”

“No. I mean the boyfriend. She’s got a dope problem—she’s always doing it, and she’s always doing them. Dopes.”

“What about the father?”

“Nah, he’s kind of nice actually. A real job and everything. She dumped him naturally. He’s fighting her for custody.”

“Why?”

“Maybe he doesn’t think junkies are the best company for an eight-year-old. And she’s always trying to poison the kid against him. It’s a fucking shame. You should’ve heard them going at it in the Tranquillity Room last week.”

“Last week…when? What day?”

“I don’t know. He comes by to drop off money for the kid. Tuesday, I think.”

Now it was coming. And it wouldn’t stop coming.

“What time Tuesday?”

“I don’t know. After lunch. Why?”

Look at it. It wants you to look at it.

Tuesday, I think. After lunch.

“What does he look like, Trudy?”

“Geez…I don’t know. About your height, I guess. Glasses. He didn’t look too fucking terrific after seeing her. She told him she was going to take the kid and disappear if he didn’t drop the whole custody thing. You know what I think? Her boyfriend wants that child support.”

About your height. Glasses.

Don’t look. Do not look.

Tuesday. After lunch.

When he argued with her in the meditation room, and then walked out looking anxious and upset.

Tuesday.

When he drove to his son’s school.

Tuesday.

When he tried to tell him that he was fighting for him and to please not believe the things his mother said about him. When he reached out to make the boy listen, but his son pulled away because all that poison had done its work.

“The boy,” I said. “He has brown hair. Cut real short—like a crew. He’s sweet looking.”

“Yeah. That’s him.”

I’m an empath, she said. I’m touching this bad man, this sexual predator, and what can I do about it—nothing, because the police won’t believe an empath like me. He’s coming Tuesday at two, but what can I do? Nothing.

How?

How did she pick me?

How?

Because.

Because she’d made me open that secret pocket.

Because one day they’d pointed me out to her—one of the masseuses—oh him, stay away, an ex-cop who used to beat people half to death.

But she didn’t stay away—she came down to the basement room where I punched holes in the wall. She talked to me. And then I ripped that pocket wide open for her and spilled my dreadful secrets all across the bed.

My brother. My guilt. My anger.

My trinity.

A kind of religion with one acolyte, and one commandment.

Vengeance is yours.

He’s a bad man, she said. He’s coming Tuesday at two. Tuesday. At two.

This man who loved his son. Who was simply trying to protect him.

From her.

Why, he said, standing at the top of that sandpit. Why?

Because anger is as blind as love, and she gave me both.

I will tell you that a drought took hold of L.A. and turned the brush in the Malibu hills to kindling. That twenty-million-dollar homes went up in smoke. That the drought dried up half the Salton Sea and sucked the water right out of that dump, and that a man disposing of his GE washing machine saw the body wrapped around an old engine casing.

I will tell you that he was ID’d and the bullet in his heart identified as a Walther .45—the kind security guards are partial to, and that a mother came forward and said she’d seen him being coerced into a car near her son’s school by another man.

I will tell you that the wheels of justice were grinding and turning and rolling inexorably toward me.

I will tell you that I am not liked much by the police officers I once worked with, but there is a code that is sometimes thick as blood. That makes an ex-partner whom you almost took down with you get hold of bank records so you might know where a Kelly Marcel has been using her VISA card.

I will tell you that there’s a motel somewhat south of La Jolla where the down-and-out pay by the week.

I will tell you that I drove there.

That I saw her drop the boy at his grandmother’s, who lived in a trailer park by the sea.

That the boyfriend took off for parts unknown.

That it’s down to her.

I will tell you that I sit in a dark motel room.

That I’ve pulled the shades down tight so she won’t see me when she walks in. So she’ll be sure to turn away from me to switch on the light.

I will tell you that I hear her now, the slam of her car door, the crunch of gravel leading up to her door.

I will tell you that my Walther .45 has two bullets in it. Two.

I will tell you the door is opening.

I will tell you that finally and at last the dark no longer scares me, that there is a peace more comforting than anger.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

Who do I say this to?

This I won’t tell you.

I won’t.