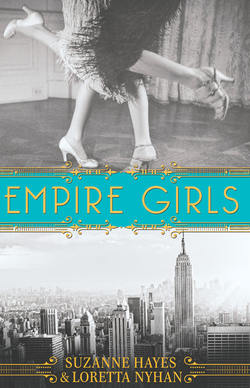

Читать книгу Empire Girls - Литагент HarperCollins USD, J. F. C. Harrison, Professor J. D. Scoffbowl - Страница 10

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

Ivy

NEW YORKERS MOVED so quickly. Pitched forward, chins leading the way, they dashed to and from destinations I could only dream about. The whole city was like a wild horse chomping at the bit—as if the island of Manhattan would soon tear itself away from the surrounding land and bolt for the wide-open sea of the future.

Jimmy, a broad-chested, raven-haired Irishman, was proving a prince of the city streets. He maneuvered the large vehicle with casual ease, pointing out restaurants and museums, secret taverns and notorious alleyways, in a voice that dipped and rose with the lilting song of the Emerald Isle. Rose disapproved—her grumblings buzzed around us like flies we casually swatted out the window. I knew what she was thinking. So new off the boat his cuffs are still damp, but even if it was true, Jimmy knew Manhattan as well as any travel guide. He also smelled deliciously of tobacco and bay rum. I perched my bottom at the edge of the jump seat and nearly got popped in the nose as he excitedly gestured at the imposing Arch of Washington Square Park.

“I live right here in Greenwich Village, and I’ll tell you it’s a place like no other,” Jimmy said as we motored past a couple embracing under the Arch. The man was bent over the girl, his mouth at her neck, his steadying hand at the curve of her back. I felt a growing sense of anticipation. Was that what it was like to live here?

“Have they no shame?” Rose muttered. Another complaint, but I was glad she’d stopped crying and started looking out the window.

“Maybe they do, but have no use for it,” I countered.

Jimmy turned onto MacDougal Street. “You’ll like Empire House,” he said. “It’s in the thick of things, a good choice if you’re in the city.” The buildings on MacDougal, connected to one another and built in the Federal style, lined the street like painted soldiers. Jimmy eased into an empty space in front of one washed in a muddy blue-gray color, its elongated, latticed windows rowed in groups of four. Red azaleas rested in stark white window boxes and the front stoop appeared freshly swept. The door, familiar from Asher’s photo, was glossy black, and the bronze plaque next to it shone in the sun.

EMPIRE HOUSE

“Don’t let the landlady intimidate you,” Jimmy said as he jumped out to grab the bags. I followed, leaving Rose in the car to sort out the money situation—I didn’t have the head for it.

I squinted up at him in the noonday sun. “I don’t let anyone get under my skin.”

He laughed. “You’ve never met Nell.” Jimmy hoisted Rose’s enormous trunk and carried it up the front stairs and into Empire House. Once he was safely inside, I could stop flirting and start eyeballing our new neighborhood. A few of the buildings had street levels that spilled open-air cafés onto the sidewalk. Colorfully dressed patrons leaned over small tables, speaking intensely about matters I could only wonder at. The scene was perfect for an artist’s eye, and I felt a pang, wishing my father stood beside me with his sketchbook.

I curled my hands over the wrought-iron bars protecting the garden level of the building next to Empire House. The windows were shuttered, however a sign on the muddy door said, Republic Theater, Revolutionaries Welcome. My pulse quickened. It certainly wasn’t the staid, cavernous auditorium in Albany, but then, this city was a different beast altogether. Theaters could pop up anywhere.

“Save your money. Whatever play they’re hawking will be closed down before you can blink twice,” Jimmy said, his breath tickling my bare neck. He’d come up without me noticing.

I turned to him and smiled. “I’m an actress,” I said, not bothering to mask my pride. “I’ll be looking for work.”

“You and half the girls in Manhattan,” he said dismissively. “But if you’re looking for theater work, you’d best stay away from these anarchists.”

The word turned my insides to jelly. Anarchists? Revolutionaries? This was going to be fun.

Jimmy laughed. “Don’t be such a tourist. You can’t walk around here with stars in your eyes.”

As we walked back to the car, Jimmy continued his lecture. “Empire House attracts the more ladylike types, but it’s still a boarding house. Always hide your best things, but don’t shove all that you own under the mattress—the girls will think you don’t trust them. Walk with a set of eyes in the back of your head, and if you’re going out at night, make sure you don’t get caught coming in late. But if you do—” here he had the most delightful twinkle in his dangerously blue Irish eyes “—run over to my place on Christopher Street and I’ll give you a warm bed to sleep in.”

I thought about the woman under the arch, and the man bent over her. I stepped closer to Jimmy. “Do you often leave your door unlocked?”

“If you’re wearing that dress, I’ll give you a key.”

I silently congratulated myself for my fashion choice that morning. I twirled once to give him a better look at how the dress dipped low in back. “A new dress for my new home,” I said. Technically, that wasn’t the truth. The dress was old. But I had a feeling that little fibs were necessary in this town and shrugged off the lie.

With a wink and a tip of his fedora, Jimmy climbed back into the driver’s seat. He drove a few yards, stopped suddenly and backed the vehicle up with a jerk.

Rose.

I’d forgotten all about her. I yanked open the passenger door and stuck my head in. Rose sat inside, an open book on her lap. “Did you tip him already?”

She nodded curtly. “Everyone’s hands are outstretched in this town. This is a greedy place.” There was a catch in her voice that told me she was trying not to cry.

A good kind of sister, a Jo March or Elizabeth Bennet, would have reached out, drawing Rose to the comfort of her solid bosom, coaxing the tears that so desperately needed shedding. But I was not a good sister. Jimmy made a sound of impatience, and embarrassment sharpened my words. “He’s got places to go,” I hissed. “Come on.”

“I can’t,” Rose whispered, her expression pained. “Maybe this was a rash decision. Let’s discuss this.”

I scooted in next to her. “Get your nose out of that book and take a hard look at this city, Rose. Can’t you feel it? All the opportunity? We can be in this world. We can make money and find Asher and have an adventure while we do it. So, please, get out of the car.”

Rose placed her book inside her travel bag, but otherwise didn’t budge.

“Why aren’t you moving?”

She closed her eyes. “Give me a moment, Ivy.”

Rose had spent a lifetime choosing stillness over action. When the Gilbert boys pressed their noses to our screened-in porch, shouting, “Come to play!” I ran outdoors. Our ragtag gang leaped into the cold river, scoured the earth for arrowheads and climbed the best mulberry trees, smearing the juicy berries on our faces until our skin turned purple. We hooted and hollered and lived. “Take it all,” my father laughed when we’d roll in the door like tumbleweeds. “It’s all yours if you want it, you little scalawags!”

Rose never joined us, preferring to stay inside, the egg tucked most firmly in the nest. She learned to knit and sew while sitting in a circle with our mother and her lady friends, who spent a few minutes discussing the women’s vote, but mostly passed the time clucking at bland, country-kitchen gossip, mundane stories that all sounded vaguely alike. Rose grew up with the mild buzz of their conversations in her ear, something that really dug at my father’s craw. “A child who grows up too closely aligned with adults assumes knowledge of a life she hasn’t yet experienced,” he always complained.

After mother died, father sent us to school in town, where Rose outshone our classmates in natural intellect, quietly assuming the top spot on the principal’s most-honored list. The teachers had high hopes for my sister, but when they offered a place in the new business class for women, she demurred. I got no offers, but took advantage of everything I could wiggle my way into—voice lessons, bit parts at the local theater, dance-a-thons, beauty contests. Rose accepted her diploma with a nod and retreated back to run Adams House. She cooked and cleaned and budgeted. The townspeople spoke kindly of Rose’s devotion to our family, but what begins as sacrifice can eventually become foolishness. My father would have said as much, but in the back of Jimmy’s car, I saw Rose gearing up to say the one word he hated, and my sister lived by—no.

One moment turned into two, then three. “You don’t have a choice in this,” I finally said, and before she could protest further, I grabbed her hands and pulled her onto the street. She fell into me, and I kicked the door shut and shouted for Jimmy to hit the gas. He did, peeling down MacDougal in a cloud of exhaust.

We sat on the curb to catch our breath. A row of silver beads had come loose from my dress and spilled onto the pavement, rolling haphazardly in different directions.

“Did I do that?” Rose said.

“I think so.”

“Well, I’m not sorry,” she snapped, but there was a faint amusement surfacing in her expression.

“Oh, you’ll fix it for me anyway,” I tossed back.

“Yes, but I’ll send you out here to search for every bead on your hands and knees.”

I burst out laughing, and the sound coaxed a genuine smile from Rose. I wasn’t the least bit sore at her. How could I be? We were in New York on a sunny, charming street in Greenwich Village. I gazed at Empire House, its front, aging yet dignified, and felt my father’s hands at my shoulders, pushing me forward—go, go, go!

Rose stood and dusted herself off. “Well, I suppose we should get ourselves a room before thieves run off with our trunks.”

We walked up the stoop together. I pulled the bell and the door flew open, creaking on its hinges. A street urchin answered, a young girl not much taller than my waist. Her small, heart-shaped face was dirty, but her dress, a cotton slip covered in primroses, was clean. She wasn’t wearing any shoes.

“Customers!” she shrieked, and pushed past us, sitting atop Rose’s trunk. “Are you moving in for good?” she asked, patting its brass lock.

“Definitely not,” Rose said, attempting to soften her words with a smile that quivered at the edges.

I crouched down, eye level with the girl. “Will you watch our trunks while we speak with the house manager?”

“Maybe,” she answered.

I nudged Rose and she dug a coin from her purse. With a sigh she placed it into the urchin’s tiny palm.

“I’m Claudia,” the girl said, pocketing the coin. “And there ain’t much you can buy in New York with a wooden nickel.” Laughing, she patted at the mass of orange-soda curls springing from her head like coils from a spent mattress. “Miss Nell is inside. Keep walking until you find yourselves in the kitchen. The cook made the coffee too strong again, so look out for flying cups.”

I watched Rose’s eyes follow the girl as she disappeared into the house. I knew my sister better than she thought. She was seeing herself in that girl, and the confused look in her eyes told me she was trying to make sense of why someone so young could put her hand out so easily. Rose didn’t know that she recognized the behavior, because she was doing the same thing in coming to New York—holding out her hand with the hope that Asher would put a nickel in it. If we could find him, that is. I wasn’t exactly sure what our odds were, but I knew one thing for certain—this city would offer us a thousand different paths toward a thousand different futures. We only had to choose the stepping-off point, and New York would take care of the rest.

We followed Claudia into the building. The sound of a woman’s complaints, imperious and disdainful, contrasted with the cheerful, feminine interior of Empire House’s front parlor. The wood floors gleamed, throwing light around a room that already sparkled with charm. Delicately etched paper—white with fine gold stripes—covered the walls. The rugs, bleached by the sun, held the faint outlines of delicate Victorian flowers, reminding me of my father’s drawings. Broad-leafed plants, green and glossy, stood tall in Grecian urns, their stems curving slightly toward the open windows.

“Well, what do you know,” I marveled. “Not so bad, is it?”

Rose’s eyes traveled over the room, lighting up when she noticed the floor-to-ceiling bookcase covering the back wall. “I suppose this will do,” she said.

I felt a surge of triumph.

The kitchen took the whole back of the house. We stood in the doorway, watching a haughty-looking woman harangue a tall, good-looking man wearing a white apron. The woman nearly crushed the man’s toes as she stepped forward, straining her neck to meet his eye. Neither of them broke away when we announced ourselves with exaggerated clearing of our throats.

“You cannot take cigarettes away from the working man and you cannot take strong coffee from the working girl,” the man shouted. “Basic human understanding!”

“We cannot afford to run through coffee like a bunch of Italian widows,” the woman growled. “Basic accounting!”

“Maybe some new tenants will offset the costs,” I interrupted.

They glared at each other for just a moment longer, and then turned toward us in unison. The woman had a regal face—a patrician nose, icy-blue eyes and a precisely painted mouth bracketed with fine lines that hinted at a lifetime of secrets. She was attractive, and anyone could tell she’d been a looker once upon a time, which probably made middle age a real wet blanket on a dry bed.

The man was a different story altogether. His features—from his neatly trimmed dark hair to his surprisingly thick-lashed eyes—were outlined in humor. His gaze danced over us, and he smiled graciously. “I’m Sonny Santino,” he said, and pointed to the bright, airy kitchen. “Welcome to my hovel.”

“I’m Ivy, and this is Rose,” I said, grinning back at him.

“Ah! The friends from Albany.”

“We’re sisters,” Rose said.

He laughed. “Sisters? You look like a pair of mismatched bookends.”

“I’m Nell Neville,” the woman said, studying us with intelligent eyes. “I hope the trip down was comfortable.”

Rose opened her mouth, but I pressed my foot against hers. “Fine and dandy.”

Nell’s mouth pulled into a smile. “Will you be looking for work here in the city?”

“I’m a capable seamstress,” Rose said. “I can do both tailoring and alterations.”

Nell turned to me. “I’m an actress,” I said. “Both tragedy and comedy.”

She nodded, unimpressed. “Your telegram said you were also coming to New York to find a lost relative. Is that still the case?”

“Yes,” Rose said quickly. She dug into her bag and pulled out her book of poetry. Inside was Mr. Lawrence’s file. “My father was Everett Adams. This is his son, Asher. Will you take a look at this photograph and see if you recognize him?”

The woman snatched Asher’s portrait from her hands, but only took a quick glance before passing it to Sonny. He studied it, his expression softening while Rose explained our mission. “Unfortunately circumstances have caused an estrangement from the family, but we are desperate to find him for legal reasons. Do you recall his face?”

“It’s my job to keep young men away from my door,” Nell said. “I own Empire House, but I manage it, as well. Any male on the premises endures my careful scrutiny. If I’d seen him, I’d remember.” She took the photograph from Sonny and gave it back to Rose. “I’m sorry we can’t be of help in that matter, but we can get you settled into your room. If you’ll come with me, we can address the paperwork.”

After tossing a final glare Santino’s way, she ushered us out of the kitchen. We followed Nell’s straight back down an adjacent hallway lined with faded fleur-de-lis wallpaper and framed photographs of hunting dogs dressed in country attire. Rose looked at me with a raised brow, doubt flooding her eyes.

“Yeah, she’s an odd bird,” I said lightly, “but aren’t we all?”

Rose sighed. “Speak for yourself.”

Nell’s small office smelled of onions and rose water. A dusty brown ledger lay at the center of a circular table. “You’re lucky we had a vacancy,” she said, turning open the book. She fussed at a drawer and extracted a fountain pen. “Sign here.”

“Could you be more specific about the rent and amenities?” Rose asked.

“You could walk three blocks and find a dozen other boarding houses that offer the same or worse,” Nell said, bristling. “There are a hundred places for girls in this city. You’re free to find one to your liking.”

I hated talk of money. I just wanted a room. The day was growing hotter, and I longed to stretch out in front of an open window with a cool cloth on my forehead.

I signed the ledger with a flourish and handed the pen to Rose, who reluctantly added her signature.

Nell separated one key from a ring holding countless copies. “You get the penthouse, top floor. As soon as you agree to the rules, you may have the key.”

My head snapped up. “Rules?”

“Oh, darling,” Nell said. “There are always rules, even in a city like this.”

EMPIRE HOUSE

RULES FOR TENANTS

Curfew is strictly enforced. The front and back doors will be locked at 10:00 p.m. nightly. On Saturday nights, the lock turns at 11:00 p.m. SHARP. (After this hour, no knocking, screaming, crying or howling will be tolerated. Sleep in the garden and learn your lesson.)

Hot showers cost fifteen cents and should last no longer than five minutes. At three cents a minute, you’re barely paying for the coal—quit your complaining. There is a timer on the small table outside the bathroom. It will be set.

Laundry services are available, but management is not held to any time constraints. You’ll get it when you get it.

Breakfast is served at 7:00 a.m.; dinner at 6:00 p.m. There is no luncheon. If you are here in the middle of the day, then you have most likely lost your job and have more pressing things to do.

Excessive noise is prohibited. Talking, singing, laughing and loud coughing are not acceptable after midnight.

No one is allowed to sit in the parlor. Ever. No exceptions.

Absolutely no consumption of alcoholic beverages. The Feds say it’s illegal and so do we. Have a nice cup of coffee instead (Five cents a cup and be sure to wash it out when you’re done).

As we gained the upper part of the house, I realized with a growing sense of unease that Empire House was only elegant at ground level. The higher we went, the shabbier it got—frayed carpet, holes in the plaster, a pervasive dampness in the air. After climbing what seemed like countless flights, we reached what I thought was the top floor, but then Nell led us to a door, which housed a narrow staircase.

I peered up, though I couldn’t see much. “Are we sleeping in the attic?”

“It’s really quite lovely,” Nell said, dropping the key into my hand. “This is for the bathroom. You won’t need any other keys. I lock up the main door at night.” With a quick smile, she began her descent back to the first floor.

“What’ll we do?” Rose asked, panic in her voice.

I shrugged. “We explore.”

Rose and I came up the stairs to find ourselves standing in the middle of an airy loft, marooned in a sea of cast-off furniture and puffs of dust.

“Our front door is a hole in the floor!” Rose said, aghast. “We might sleepwalk and tumble down the stairs!”

I didn’t want to admit I’d had a similar thought. “It ain’t the Ritz, but it’s not so bad,” I said, but I was throwing her a line—it was one step above a flophouse. One slim window faced MacDougal Street, and sunlight weakly filtered in through a dirty skylight, casting strange shadows on the two twin beds, huddled like starving children in the middle of the room, and an old-fashioned dressing table with an overlarge mirror. The walls were painted a leaden gray. Our trunks sat on a frayed rug. Leeched of all color, it covered a small section of well-used oak floors.

“We have roommates,” Rose whispered, pointing to a closet cut into the middle of the far side wall. Through it another room could be seen. I spotted two female figures moving to and fro, but it was like I was peering at them through the wrong end of the telescope. The gals noticed me and squealed, and they both darted through the slim passageway, fluttering into our room like birds escaping the nest.

One had brown hair that would be mousy, had it not been cut in the most precise bob I’d ever seen. She introduced herself as Maude. The other’s hair was blond, not golden, like Rose’s, but honey-colored, as though she’d started off light but darkened with age. She had the kind of eyes—keen and electric—that missed nothing. This was Viv.

“How’d you gals get stuck with the penthouse?” Viv asked.

“Just lucky, I guess,” I said, keeping my tone jokey. “What’s there to do for fun around here?”

Maude winked. “Oh, anything you set your heart on. Anything at all.”

Rose glanced uneasily at the corridor linking our rooms. “We were hoping for a private room. We’re paying a steep sum—”

“Don’t worry about us,” Viv interjected. “We won’t bug you unless you ask for it.”

Maude rolled her eyes. “Don’t mind her. She’s still working off a bender.”

“But isn’t drinking against the rules?” The words had tumbled from Rose’s mouth, and she colored, instantly aware of her mistake. “Oh,” she said, her voice soft. “It must have been your birthday.”

“Nope,” Viv said. She sat on Rose’s trunk and began to brazenly readjust her stockings. Maude joined her and began to study her own seams. There are always leaders and followers, I thought, and it only took a minute to figure out which was which.

Viv focused her attention on my sister. “Tuesdays are Tom Collins nights,” she explained. “I figure it’s a neglected day of the week, why not give it a distinguishing characteristic?” The girls erupted in laughter.

Obviously unsure of how to respond, Rose looked at me in silent appeal. “You gals been here awhile?” I asked, changing the subject.

“Long enough to know what’s what,” Viv answered.

I caught Rose’s eye and gave a little nod. Once again she extracted Asher’s photograph and placed it on the trunk. “We’re looking for someone,” Rose said, and I noted a change in her voice, a sadness. Was she already feeling defeated? “That’s him. Does he look familiar?”

Viv picked it up first. She held it very close to her face, and I realized she must need glasses. “No,” she said, handing the portrait to Maude. “But if he shows up, be sure to send him my way. He’s a looker.”

“He’s my half brother,” Rose said quietly.

“I was just kidding,” Viv said by way of apology.

Maude returned the photograph. “He looks familiar, but so do half the mugs in this city. I’m sorry I can’t say for sure, but if you want to ask about someone, I’d go see Nell. She’s been here since the Dutch waltzed down Fifth Avenue in their fur coats.”

Viv barked a laugh. “If you can catch her on a good day.”

“We’ve already asked her,” Rose said.

“Well, that’s that, then,” Viv said, her tone growing friendlier. “So, since we’re going to be sharing the penthouse, let’s get acquainted. On this little island you’re either a party girl or a workaday drudge. Which are ya?”

Rose brought a hand to her cheek. “Are those the only choices?”

Maude laughed. “In this city, it’s one or the other.” She appraised my sister with new eyes. “Hey, you’re a kick. I hadn’t realized.”

“But she still hasn’t answered the question.” Viv’s smile was mean. “Drudge it is.”

“There’s nothing wrong with a good day’s work,” Rose said tightly.

“Now that’s the bald-honest truth,” Maude attested, and Rose shot her a grateful look.

I stepped into the conversation, hand on my hip. “We’re looking for work, but we never turn down a party.”

“Well, now that we’ve got that settled, let’s talk the lay of the land,” Viv said, standing up. She patted Rose’s trunk. “That half-baked closet in between us might be as wide as a cigarette case, but we’re lucky—the girls downstairs hang their clothes on a line in the hallway. None of our rags ever go missing. The girls downstairs are fortunate if they can hold on to a dress more than a season. The smart ones keep their good dresses pressed between their mattress and box spring.”

“Don’t forget Claudia,” Maude interjected. “She lives here, too.”

Rose smiled, and I watched the straight line of her back give a little. “We met Claudia downstairs. Is she a relation of yours?”

“Claudia’s a street rat Nell took in,” Viv explained. “She sleeps in that narrow room, tucked under our dresses. The wall juts out, so she’s got her own spot under the eave.”

“Lucky her,” Rose said with a sigh.

“You bet,” Viv said, misinterpreting her sarcasm. “In fact, it looks like it’s everyone’s red-letter day. Daisy moved out around three weeks ago. Nell thought she’d have to put an ad in the Daily if she couldn’t rent this place soon.” She paused, taking in the grimy walls and bare mattresses. “I have no idea why it’s so hard to let.”

“Oh, it ain’t so bad.” Maude sniffed. “We’re lucky to have it.”

I studied our surroundings more closely. The room could be charming with a little bit of spit and polish. Daisy had either been a slob or she’d been in a hurry. She’d left some handkerchiefs on the floor next to one of the beds, hairpins and magazines on the dresser and some restaurant cards stuck to the mirror. Those might come in handy, give us a lay of the land. “Daisy blew out of here pretty quick, huh?”

Viv smiled knowingly. “She’s either headed to the convent or the preacher.”

“So old Daisy was a party girl?” I said with a wink.

Maude’s eyebrows lifted. “Daisy was a workaday drudge,” she said, obviously still marveling over that shocker. “A seamstress. And you wouldn’t believe—”

“Perhaps we could discuss Daisy’s indiscretions later,” Rose interrupted, exhaustion creeping into her voice, “after we’ve unpacked.”

Viv pulled at Maude’s collar. “Let’s leave the girls to their new home.”

“We’re going out for a stroll if you want to join us,” Maude said as Viv pulled her down the narrow staircase. “Be downstairs in ten if you want to tag along!”

I sat on one of the beds after they’d left. The mattress felt like it was made of slate. I watched Rose unpack, her movements slow. Mouth compressed, eyes slightly unfocused, she was lost to the thoughts inside her.

“What’s eatin’ you?”

She took Father’s painting of Empire House from her trunk and placed it on the dresser. She contemplated it for a moment and then sat on the bed opposite me. “Do you think they’re all telling the truth, Ivy? I have an odd feeling.”

“When your instinct talks you should listen. Wouldn’t father have said the same?” I thought for a moment. “I did wonder why Nell barely gave Asher’s photo a glance. I thought she was impatient, but maybe there’s something else? Maude did say Nell’s been here the longest, so if anyone would have come across him it would be her.”

“Maybe,” Rose said distractedly, but then her eyes sparked to life. “I know what’s bothering me! That cook downstairs. He didn’t say if he knew Asher or not. He didn’t say anything at all after looking at the photograph.”

I grinned at my sister. “Reading all those books is finally paying off! Maybe we’re barking up the wrong tree, but if someone’s keeping a secret, I can’t imagine it would stay buried for too long around here. We’re going to find Asher before you need to change your dress. I know it.”

“Ivy?”

“Hmm?”

“Have you ever considered what might happen if and when we do find him?” Rose was staring up at the skylight as she asked the question. The light played across her worried face.

I got up and wordlessly helped her unpack her books. I wanted to say I’d thought the whole thing through, but I hadn’t. Rose was trying to prepare me for disappointment, and I couldn’t consider that. Not for a moment.

“You’ve got something to write with in that trunk, dontcha?” I asked, changing the subject.

“Are you feeling self-reflective?” Rose teased while sifting through her things. “Has Greenwich Village already turned you into a philosopher?”

“Now wouldn’t that be a kick?”

Empire House

June-something-or-other, 1925