Читать книгу Georgie and Elsa: Jorge Luis Borges and His Wife: The Untold Story - Литагент HarperCollins USD, F. M. L. Thompson - Страница 10

5. Meeting Borges and Setting Out with a Master

ОглавлениеIn the late autumn of 1967, while Borges was mentally preparing his third lecture and Georgie and Elsa were nursing their marital bliss, I innocently entered their lives.

It was all a matter of accidents, coincidences, and luck. I’d been reading bits of Latin American poets, got hooked on Borges, and decided to repair to Schoenhof’s foreign bookshop, in Harvard Square, for a copy of his collected poems in Spanish. When the clerk handed me the book he casually announced that Borges would be speaking there at Harvard the next week. I had no inkling Borges might be anywhere but in his own country.

I was in Memorial Hall that next week – it was 15 November – to hear his second Norton Lecture, a talk on ‘The Metaphor’. Borges’s spoken English immediately struck me, as did his views on his chosen subject. A week passed, and I sat down and wrote to him. My letter said that I was interested in producing a volume of his poems in English translation along the lines of the fifty poems from Jorge Guillén’s Cántico that I had published two years before. It was all a stab in the dark. I had no idea of the regard in which Borges held Guillén, nor had I any idea that Guillén’s daughter Teresa and wife Irene were attending Borges’s classes on Argentine writers.

Within a week I had a reply from John Murchison, Borges’s Harvard secretary, to tell me that Borges was pleased with my suggestion and ‘would be delighted to have you phone him at his home …’

A few days later I phoned. A woman answered, it was Elsa, but as I was unused to Argentine Spanish I thought hers was an Italian voice. She seemed to be speaking Italian when she called out, ‘Georgie’. This was my introduction to the accent and intonation of rapid-fire porteño Spanish.

Borges answered, I identified myself, and he was at once lively and interested. He spoke in a clipped voice, with an English accent, and asked me right off what edition of the poems I had. When I told him, he said, ‘Well, that’s not the latest.’

‘Oh, dear.’

‘That’s of no consequence,’ he said. ‘I don’t know if the new edition is even in print yet. I have added a few new poems – all short ones. I have them all memorized.’

Then he asked would I come today. What time? Six o’clock. He gave me the address and repeated the apartment number twice. Eagerly, he also asked me to bring some of the translations. I told him he had misunderstood; I hadn’t any translations yet but would be commissioning them.

‘Well, come and we’ll talk,’ he said, his enthusiasm undiminished.

It did not occur to me then that Borges would have asked Teresa Gilman, or perhaps even Guillén himself, about me. I know in their loyalty they would have given me a warm report. Elsa would have invested this train of events with prophetic significance, calling it fate. But predetermination is not one of my beliefs; what was taking place at breakneck speed I knew to be just dumb luck.

That evening, for a couple of hours, Borges and I sat at a wooden table opposite each other on the benches of the flat’s old-fashioned built-in breakfast nook. We discussed the planned volume in general terms and then went over some specific lines in a couple of poems I had been tinkering with in English translation.

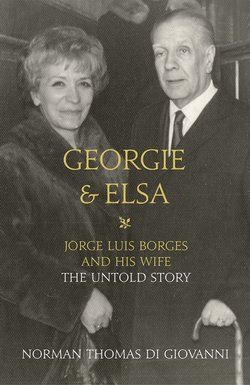

The present book – the story I am trying to tell here – is about Georgie and Elsa. I want it to be a book about two married people, one of whom happens only incidentally to be a famous writer. My interest is strictly in them, not in literary criticism. And yet it was the work that Borges and I were embarking on that was the glue that held the three of us together. Perhaps, then – as an aside – the briefest, pedantry-free description of our daily enterprise would not be out of place.

I first read through his poems – they dated from 1923 to 1967 – and then joined him to hammer out a suitable broad selection. I brought notes, and while Borges would volunteer information about this or that poem I would scribble down jottings that might later prove useful to a prospective translator. Our views of what to include or exclude in a volume of a hundred poems rarely failed to coincide. Next I would take to our meetings a literal line-by-line handwritten draft of the poems, each of which we discussed at length. As Borges was blind, I read him one line at a time and added changes and corrections as he guided me.

There was a long history of visual abnormalities running through the male side of Borges’s family. His father before him had lost his sight, and from his early years Borges was severely myopic. His vision had gradually deteriorated down the years until around 1955, when he could no longer read. When I met him he was able to distinguish the colour yellow as a luminous patch and so had a preference for yellow neckties. This too left him in time. When our books were published he would hold the title page up close to his face and make out the large letters. I noticed that he saw outlines better in bright light, and that his psychological state was a factor as well. This blindness worked to the advantage of our translations, since everything had to be read to him and demanded his strict attention.

For the rest, the task was one of lengthy administrative duties. On my own I began to match up poems and translators, beginning with some of the same poets who had assisted me in the Guillén volume. This time I included myself among the translators. I corresponded with each contributor, criticized their English versions when they came back to me (often toing and froing with them several times per poem), and generally kept my stable of writers working. When I felt a poem was finished, I read it to Borges for a final nod of approval.

Other administrative duties consisted of raising funds to pay the translators and, most important of all, finding a publisher. It was a whirlwind of activity. I first met Borges at his flat on 4 December 1967. Before that month was out I had landed my publisher, Seymour Lawrence, and Borges had written to his, Carlos Frías, in Buenos Aires – dictating the letter to me – to secure English-language rights. I was amused and flattered when in the letter he referred to me as ‘the onlie begetter of this generous enterprise’. He quickly explained that Frías was also a professor of English literature, so the Shakespeare link would not be wasted on him.

Work on these selected poems began in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and they were three years in the making before being finished in Buenos Aires. The book was then a fourth year in production.

I have mentioned that in the months before I met him Borges had chosen – had been forced to choose – isolation as his daily lot. Worse than his isolation was his stark loneliness. No one came to visit, he told me, and after a while he asked if I could come to work with him on Sundays. His empty Sundays seemed to him to yawn on for ever. I was puzzled by this – the crowds at his public lectures, the emptiness at home – but I did not press him for an explanation. In the flat there was great tension between him and Elsa, which I feigned not to notice. I could see that he was immediately cheered by our work together, and he told me it gave him justification for his existence.

I said he told me that no one came to see him, but I remember that for a couple of days during my early visits a black boy, who may have been a Harvard student with an interest in writing, would be sitting in the kitchen with Borges. The young man said nothing, and Borges said nothing to him. I felt that Borges wanted to get rid of him by maintaining silence and not responding. As Borges snubbed him, the lad stopped coming. Borges never mentioned the incident nor did I.

Fani, the Borges’s Argentine maidservant, reported that one day in Buenos Aires Borges received a visit from two Brazilian women. ‘They stayed the whole afternoon,’ Fani said. ‘When they left the señor came to the kitchen and asked me what they were like physically. I told him they were blacks. “What do you mean blacks? Why didn’t you tell me? ¡Qué horror, I would have thrown them out!”’

I don’t know what it was about black people, but he did have an aversion to them. He sometimes wrinkled his nose and spoke of their catinga, an Argentine word for the smell of their sweat.

For her part, Elsa too seemed pleased to welcome me into the fold. I lifted her out of her gloom. My presence gave her more time for herself, needed space from Borges, and some new company she could trust.