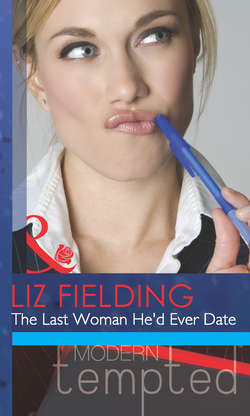

Читать книгу The Last Woman He'd Ever Date - Liz Fielding - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Cranbrook Park for Sale?

THE future of the Cranbrook Park has been the subject of intense speculation this week after a move by HMRC to recover unpaid taxes sparked concern amongst the estate’s creditors.

Cranbrook Park, the site of a 12th century Abbey, the ruins of which are still a feature of the estate, has been in continuous occupation by the same family since the 15th century. The original Tudor hall, built by Thomas Cranbrook, has been extended over the centuries and the Park, laid out in the late eighteenth century by Humphrey Repton, has long been at the heart of Maybridge society with both house and grounds generously loaned for charity events by the present baronet, Sir Robert Cranbrook.

The Observer contacted the estate office today for clarification of the situation, but no one was available for comment. —Maybridge Observer, Thursday 21 April

* * *

Sir Robert Cranbrook glared across the table. Even from his wheelchair and ravaged by a stroke he was an impressive man, but his hand shook as he snatched the pen his lawyer offered and signed away centuries of power and privilege.

‘Do you want a sample of my DNA, too, boy?’ he demanded as he tossed the pen on the table. His speech was slurred but the arrogant disdain of five hundred years was in his eyes. ‘Are you prepared to drag your mother’s name through the courts in order to satisfy your pretensions? Because I will fight your right to inherit my title.’

Even now, when he’d lost everything, he still thought his name, the baronetcy that went with it, meant something.

Hal North’s hand was rock steady as he picked up the pen and added his signature to the papers, immune to that insulting ‘boy.’

Cranbrook Park meant nothing to him except as a means to an end. He was the one in control here, forcing his enemy to sit across the table and look him in the eye, to acknowledge the shift in power. That was satisfaction enough.

Nearly enough.

Cranbrook’s pawn, Thackeray, hadn’t lived to witness this moment, but his daughter was now his tenant. Evicting her would close the circle.

‘You can’t afford to fight me, Cranbrook,’ he said, capping the pen and returning it to the lawyer. ‘You owe your soul to the tax man and without me to bail you out you’d be a common bankrupt man living at the mercy of the state.’

‘Mr North…’

‘I have no interest in claiming you as my father. You refused to acknowledge me as your son when it would have meant something,’ he continued, ignoring the protest from Cranbrook’s solicitor, the shocked intake of breath from around the room. It was just the two of them confronting the past. No one else mattered. ‘I will not acknowledge you now. I don’t need your name and I don’t want your title. Unlike you, I did not have to wait for my father to die before I took my place in the world, to be a man.’

He picked up the deeds to Cranbrook Park. Vellum, tied with red ribbon, bearing a King’s seal. Now his property.

‘I owe no man for my success. Everything I am, everything I own, Cranbrook, including the estate you have squandered, lost because you were too idle, too fond of easy living to hold it, I have earned through hard work, sweat—things you’ve always thought beneath you. Things that could have served you. Would have saved you from this if you were a better man.’

‘You’re a poacher, a common thief…’

‘And now I’m dining with presidents and prime ministers, while you’re waiting for God in a world reduced to a single room with a view of a flower-bed instead of the park created by Humphrey Repton for one of your more energetic ancestors.’

Hal turned to his lawyer, tossed him the centuries-old deeds as casually as he would toss a newspaper in a bin and stood up, wanting to be done with this. To breathe fresh air.

‘Think about me sitting at your desk as I make that world my own, Cranbrook. Think about my mother sleeping in the Queen’s bed, sitting at the table where your ancestors toadied to kings instead of serving at it.’ He nodded to the witnesses. ‘We’re done here.’

‘Done! We’re far from done!’ Sir Robert Cranbrook clutched at the table, hauled himself to his feet. ‘Your mother was a cheating whore who took the money I gave her to flush you away and then used you as a threat to keep her useless drunk of a husband in a job,’ he said, waving away the rush to support him.

Hal North had not become a multimillionaire by betraying his emotions and he kept his face expressionless, his hands relaxed, masking the feelings boiling inside him.

‘You can’t blackmail an innocent man, Cranbrook.’

‘She didn’t have to be pushed very hard to come back for more. Years and years more. She was mine, bought and paid for.’

‘Hal…’ The quiet warning came from his lawyer. ‘Let’s go.’

‘Sleeping in a bed made for a queen won’t change what she is and no amount of money will make you anything but trash.’ Cranbrook raised a finger, no longer shaky, and pointed at him. ‘Your hatred of me has driven you all these years, Henry North and now everything you ever dreamed of has finally fallen into your lap and you think you’ve won.’

Oh, yes…

‘Enjoy your moment, because tomorrow you’re going to be wondering what there’s left to get out of bed for. Your wife left you. You have no children. We are the same you and I…’

‘Never!’

‘The same,’ he repeated. ‘You can’t fight your genes.’ His lips curled up in a parody of a smile. ‘That’s what I’ll be thinking about when they’re feeding me through a tube,’ he said as he collapsed back into the chair, ‘and I’ll be the one who dies laughing.’

* * *

Claire Thackeray swung her bike off the road and onto the footpath that crossed Cranbrook Park estate.

The No Cycling sign had been knocked down by the quad bikers before Christmas and late for work, again, she didn’t bother to dismount.

She wasn’t a rule breaker by inclination but no one was taking their job for granted at the moment. Besides, hardly anyone used the path. The Hall was unoccupied but for a caretaker and any fisherman taking advantage of the hiatus in occupancy to tempt Sir Robert’s trout from the Cran wouldn’t give two hoots. Which left only Archie and he’d look the other way for a bribe.

As she approached a bend in the path, Archie, who objected to anyone travelling faster than walking pace past his meadow, charged the hedge. It was terrifying if you weren’t expecting it—hence the avoidance by joggers—and pretty unnerving if you were. The trick was to have a treat ready and she reached in her basket for the apple she carried to keep him sweet.

Her hand met fresh air and as she looked down she had a mental image of the apple sitting on the kitchen table, before Archie—not a donkey to be denied an anticipated treat—brayed his disapproval.

Her first mistake was not to stop and dismount the minute she realised she had no means of distracting him, but while his first charge had been a challenge, his second was the real deal. While she was still on the what, where, how, he leapt through one of the many gaps in the long-neglected hedge, easily clearing the sagging wire while she was too busy pumping the pedals in an attempt to outrun him to be thinking clearly.

Her second mistake was to glance back, see how far away he was and the next thing she knew she’d come to an abrupt and painful halt in a tangle of bike and limbs—not all of them her own—and was face down in a patch of bluebells growing beneath the hedge.

Archie stopped, snorted, then, job done, he turned around and trotted back to his hiding place to await his next victim. Unfortunately the man she’d crashed into, and who was now the bottom half of a bicycle sandwich, was going nowhere.

‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’ he demanded.

‘Smelling the bluebells,’ she muttered, keeping very still while she mentally checked out the ‘ouch’ messages filtering through to her brain.

There were quite a lot of them and it took her a while, but even so she would almost certainly have moved her hand, which appeared to be jammed in some part of the man’s anatomy if it hadn’t been trapped beneath the bike’s handlebars. Presumably he was doing the same since he hadn’t moved, either. ‘Such a gorgeous scent, don’t you think?’ she prompted, torn between wishing him to the devil and hoping that he hadn’t lost consciousness.

His response was vigorous enough to suggest that while he might have had a humour bypass—and honestly if you didn’t laugh, well, with the sort of morning she’d had, you’d have to cry—he was in one piece.

Ignoring her attempt to make light of the situation he added, ‘This is a footpath.’

‘So it is,’ she muttered, telling herself that he wouldn’t have been making petty complaints about her disregard for the by-laws if he’d been seriously hurt. It wasn’t a comfort. ‘I’m so sorry I ran into you.’ And she was. Really, really sorry.

Sorry that her broad beans had been attacked by a blackfly. Sorry that she’d forgotten Archie’s apple. Sorry that Mr Grumpy had been standing in her way.

Until thirty seconds ago she had merely been late. Now she’d have to go home and clean up. Worse, she’d have to ring in and tell the news editor she’d had an accident which meant he’d send someone else to keep her appointment with the chairman of the Planning Committee.

He was going to be furious. She’d lived on Cranbrook Park all her life and she’d been assigned to cover the story.

‘It’s bad enough that you were using it as a race track—’

Oh, great. There you are lying in a ditch, entangled with a bent bicycle, with a strange man’s hand on your backside—he’d better be trapped, too—and his first thought was to lecture her on road safety.

‘—but you weren’t even looking where you were going.’

She spat out what she hoped was a bit of twig. ‘You may not have noticed but I was being chased by a donkey,’ she said.

‘Oh, I noticed.’

Not sympathy, but satisfaction.

‘And what about you?’ she demanded. Although her field of vision was small, she could see that he was wearing dark green coveralls. And she was pretty sure that she’d seen a pair of Wellington boots pass in front of her eyes in the split second before she’d crashed into the bank. ‘I’d risk a bet you don’t have a licence for fishing here.’

‘And you’d win,’ he admitted, without the slightest suggestion of remorse. ‘Are you hurt?’

Finally…

‘Only, until you move I can’t get up,’ he explained.

Oh, right. Not concern, just impatience. What a charmer.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she said, with just the slightest touch of sarcasm, ‘but you shouldn’t move after an accident.’ She’d written up a first-aid course she’d attended for the women’s page and was very clear on that point. ‘In case of serious injury,’ she added, to press home the point that he should be sympathetic. Concerned.

‘Is that a fact? So what do you suggest? We just lie here until a paramedic happens to pass by?’

Now who was being sarcastic?

‘I’ve got a phone in my bag,’ she said. It was slung across her body and lying against her back out of reach. Probably a good thing or she’d have been tempted to hit him with it. What the heck did he think he was doing leaping out in front of her like that? ‘If you can reach it, you could dial nine-nine-nine.’

‘Are you hurt?’ She detected the merest trace of concern so presumably the message was getting through his thick skull. ‘I’m not about to call out the emergency services to deal with a bruised ego.’

No. Wrong again.

‘I might have a concussion,’ she pointed out. ‘You might have concussion.’ She could hope…

‘If you do, you have no one but yourself to blame. The cycle helmet is supposed to be on your head, not in your basket.’

He was right, of course, but the chairman of the Planning Committee was old school. Any woman journalist who wanted a story had better be well-groomed and properly dressed in a skirt and high heels. Having gone to the effort of putting up her hair for the old misogynist, she wasn’t about to ruin her hard work by crushing it with her cycle helmet.

She’d intended to catch the bus this morning. But if it weren’t for the blackfly she could have caught the bus…

‘How many fingers am I holding up?’ Mr Grumpy asked.

‘Oh…’ She blinked as a muddy hand appeared in front of her. The one that wasn’t cradling her backside in a much too familiar manner. Not that she was about to draw attention to the fact that she’d noticed. Much wiser to ignore it and concentrate on the other hand which, beneath the mud, consisted of a broad palm, a well-shaped thumb, long fingers… ‘Three?’ she offered.

‘Close enough.’

‘I’m not sure that “close enough” is close enough,’ she said, putting off the moment when she’d have to test the jangle of aches and move. ‘Do you want to try that again?’

‘Not unless you’re telling me you can’t count up to three.’

‘Right now I’m not sure of my own name,’ she lied.

‘Does Claire Thackeray sound familiar?’

That was when she made the mistake of picking her face out of the bluebells and looking at him.

Forget concussion.

She was now in heart-attack territory. Dry mouth, loss of breath. Thud. Bang. Boom.

Mr Grumpy was not some irascible old bloke with a bee in his bonnet regarding the sanctity of footpaths—even if he was less than scrupulous about where he fished—and a legitimate grievance at the way she’d run him down.

He might be irritable, but he wasn’t old. Far from it.

He was mature.

In the way that men who’ve passed the smooth-skinned prettiness of their twenties and fulfilled the potential of their genes are mature.

Not that Hal North had ever been pretty.

He’d been a raw-boned youth with a wild streak that had both attracted and frightened her. As a child she’d yearned to be noticed by him, but would have run a mile if he’d as much as glanced in her direction. As a young teen, she’d had fantasies about him that would have given her mother nightmares if she’d even suspected her precious girl of having such thoughts about the village bad boy.

Not that her mother had anything to worry about where Hal North was concerned.

She was too young for anything but the muddled fantasies in her head, much too young for Hal to notice her existence.

There had been plenty of girls of his own age, girls with curves, girls who were attracted to the aura of risk he generated, the edge of darkness that had made her shiver a little—shiver a lot—with feelings she didn’t truly understand.

It had been like watching your favourite film star, or a rock god strutting his stuff on the television. You felt a kind of thrill, but you weren’t sure what it meant, what you were supposed to do with it.

Or maybe that was just her.

She’d been a swot, not one of the ‘cool’ group in school who had giggled over things she didn’t understand.

While they’d been practising being women, she’d been confined to experiencing it second-hand in the pages of nineteenth-century literature.

He’d bulked up since the day he’d been banished from the estate by Sir Robert Cranbrook after some particularly outrageous incident; what, she never discovered. Her mother had talked about it in hushed whispers to her father, but instantly switched to that bright, false change-the-subject smile if she came near enough to hear and she’d never had a secret-sharing relationship with any of the local girls.

Instead, she’d filled her diary with all kinds of fantasies about what might have happened, where he’d gone, about the day he’d return to find her all grown up—no longer the skinny ugly duckling but a fully fledged swan. Definitely fairy-tale material…

The years had passed, her diary had been abandoned in the face of increasing workloads from school and he’d been forgotten in the heat of a real-life romance.

Now confronted by him, as close as her girlish fantasy could ever have imagined, it came back in a rush and his power to attract, she discovered, had only grown over the years.

He was no longer a raw-boned skinny youth with shoulders he had yet to grow into, hands too big for his wrists. He still had hard cheekbones, though. A take-it-or-leave-it jaw, a nose that suggested he’d taken it once or twice himself. The only softness in his face, the sensuous curve of his lower lip.

It was his eyes, though, so dark in the shadow of overhanging trees, which overrode any shortfall in classic good looks. They had the kind of raw energy that made her blood tingle, her skin goose, had her fighting for breath in a way that had nothing to do with being winded by her fall.

She reminded herself that she was twenty-six. A responsible adult holding down a job, supporting her child. A grown woman who did not blush. At all.

‘I’m surprised you recognised me,’ she said, doing her best to sound calm, in control, despite the thudding heart, racing pulse, the mud smearing her cheek. The fact that her hand was jammed between his legs. Nowhere near in control enough to admit the intimacy of a name she had once whispered over and over in the dark of her room.

She snatched her hand away, keeping her ‘ouch’ to herself as she scraped her knuckles on the brake lever and told herself not to be so wet.

‘You haven’t changed much.’ His tone suggested that it wasn’t a subject for congratulation. ‘Still prim, all buttoned- up. And still riding your bike along this footpath. I’ll bet it was the only rule you ever broke.’

‘There’s nothing big about breaking rules,’ she said, stung into attack by his casual dismissal of her best suit. The suggestion that she still looked the same now as when she’d worn a blazer and a panama hat over hair braided in a neat plait. ‘Nothing big about hiding under the willows, tickling Sir Robert’s trout, either. Not the only rule you ever broke,’ she added.

‘Sharper tongued, though.’

That stung, too. The incident might have been painful but come on… She’d been chased by a donkey and every other man she knew would be at the very least struggling to hide a grin right now. Most would be laughing out loud.

‘As for the trout,’ he added, ‘Robert Cranbrook never did own them, only the right to stand on the bank with a rod and fly and attempt to catch them. He can’t even claim that now.’

‘Maybe not,’ she said, doing her best to ignore the sensory deluge, ‘but someone can.’ And sounded just as prim and buttoned-up as she apparently looked. ‘HMRC if the rumours about the state of Sir Robert’s finances are to be believed and the Revenue certainly won’t take kindly to you helping yourself.’

Buttoned-up and priggish.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said, making a determined effort to lighten the mood, ‘I’ll look the other way, just this once, if you’ll promise to ignore my misdemeanour.’

‘Shall we get out of this ditch before you start plea bargaining?’ he suggested.

Plea bargaining? She’d been joking, for heaven’s sake! She wasn’t that buttoned-up. She wasn’t buttoned-up at all!

‘You don’t appear to have a concussion,’ he continued, ‘and unless you’re telling me you can’t feel your legs, or you’ve broken something, I’d rather leave the paramedics to cope with genuine emergencies.’

‘Good call.’ As an emergency it was genuine enough—although not in the medical sense—but if she was the subject of her own front-page story she’d never hear the last of it in the newsroom. ‘Hold on,’ she said, not that he appeared to need encouragement to do that. He hadn’t changed that much. ‘I’ll check.’

She did a quick round up of her limbs, flexing her fingers and toes. Her shoulder had taken the brunt of the fall and she knew that she would be feeling it any moment now, but it was probably no more than a bruise. The peddle had spun as her foot had slipped, whacking her shin. She’d scraped her knuckles on the brake lever and her left foot appeared to be up to the ankle in the cold muddy water at the bottom of the ditch but everything appeared to be in reasonable working order.

‘Well?’ he demanded.

‘Winded.’ She wouldn’t want him to think he was the cause of her breathing difficulties. ‘And there will be bruises, but I have sufficient feeling below the waist to know where your hand is.’

He didn’t seem to feel the need to apologise but then she had run into him at full tilt. She really didn’t want to think about where he’d be black and blue. Or where her own hand had been.

‘What about you?’ she asked, somewhat belatedly.

‘Can I feel my hand on your bum?’

The lines bracketing his mouth deepened a fraction and her heart rate which, after the initial shock of seeing him, had begun to settle back down, thudding along steadily with only an occasional rattle of the cymbals, took off on a dramatic drum roll.