Читать книгу The Book Vault - Liz Filleul - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

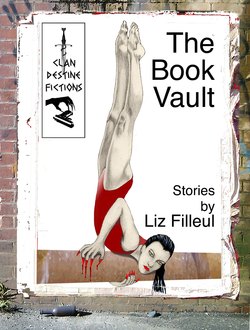

THE BOOK VAULT Not What You Think We Are

ОглавлениеArad, Romania, September 1991

The first time I saw him, I picked him as a pervert. So many of them were - why else would middle-aged men want to photograph prepubescent gymnasts in leotards? Sure, they claimed their newspapers had sent them; that they usually covered football or rugby. That might have been true in the days of Olga Korbut and Nadia Comaneci, but it certainly wasn't true now that gymnastics was no longer a must-see sport.

This overweight, balding sleazebag was a recently retired PE teacher from Queensland, Australia called Gary Markham. He'd turned gymnastics photo-journalist for pin money, to supplement his superannuation. And to claim tax deductions on overseas travels. He wasn't even trying to hide the fact that he was a creep. There he was now, loitering by the beam with his camera, waiting for the girls to straddle. Ugh.

One of the Australian girls, Rowena Harris, was wobbling on the beam when Markham strolled over to me and our official translator, Corinna Ruzici.

'I was wondering if I could have an interview with Eugenia Sidon,' he said. Corinna began translating, but I was fluent in English and interrupted her.

'Rowena Harris is training on the beam right now. You have no interest in watching her?' I asked, glowering at him.

Corinna instantly glared at me. Hostility to foreign visitors, particularly Western journalists, might have been de rigeur during the Communist era, but it was not okay now. The upcoming meet between Romania and Australia was a friendly, so the idea was to be, well, friendly. We were supposed to be showing our Australian visitors the new, post-Communist Romania. Their gymnasts had trained alongside us in the training centre at Arad leading up to tomorrow's competition. After that, the Australian delegation would be taken on bus tours, shown some of Romania's sights. The Romanian Tourist Association hoped the invited journalists would commend Romania and lure more Australian tourists with their dollars. I just wanted them to rave about the new wave of young Romanian gymnastics superstars. All coached by me.

Gary Markham seemed unoffended.

'I've interviewed Rowena a few times,' he said, 'and I know her routines by heart. Everyone's saying Eugenia's going to be the next Nadia. I'd like to talk to her.'

I reluctantly agreed and waved to Eugenia, who'd just finished practising a newly learnt release-and-catch move on the uneven bars. She came over straightaway. Apart from her blonde hair, she looked exactly like the rest of the team - tiny, emaciated, pony-tailed and poker-faced.

Gary Markham beamed at Eugenia when she joined us. He boomed down at her (even he looked tall beside her four foot nine inches) like a jocular uncle.

'Gidday, Eugenia! I won't keep you long. I just have a few questions for you.'

Corinna translated and Eugenia eyed Markham sourly.

Questions from the press could sometimes be awkward, given all that Romanian gymnastics had to hide. But Gary Markham wasn't a very good journalist. He just trotted out the usual questions that the girls had rehearsed for.

'How many hours a day do you train?'

'What do you have to eat each day?

'How old are you?'

'How old were you when you took up gymnastics?'

'What made you take it up?'

'How long have you been doing gymnastics?'

'Why do you never smile?'

Eugenia answered mechanically, with a mixture of truth and lies. Even back in my day, every Romanian gymnast had been programmed to know when you could tell the truth and when you couldn't. She told Markham through Corinna that she trained for three hours every day, in the afternoon, after school. (Which was precisely what they had done all week, with the Australians there.) She ate meat and salad, drank lots of milk and yes, of course, she ate chocolate as well. She'd had some only that morning! She was fifteen years old. Yes, everybody told her she only looked about ten, and looking so young was a real pain, but her mother said she'd be happy if she looked five years younger when she turned fifty. She'd taken up gymnastics when she was five, because she loved doing handstands and cartwheels and her mother thought she could be just like Nadia Comaneci. She'd been doing gymnastics for ten years. (In the past, some gymnasts had slipped up with that question because they'd had to lie about their age and the numbers didn't add up.) And she took her gymnastics seriously; why should she smile when executing a back somersault on the four-inch beam?

Markham scribbled down notes. He asked her what her ambitions were and she told him she wanted to be the next Olympic champion. Then he asked her what she planned to do after gymnastics. She looked floored by this and said she didn't know.

'Coach, maybe?' I prompted her.

Eugenia shrugged.

'Didn't you do gymnastics yourself once?' he asked me.

I sent Eugenia back to practise her vault. She'd been working on the vault and I really wanted her to impress the judges. I told him that yes, I had done gymnastics but I'd retired at thirteen; I'd never made it to the national team.

The youngest member of the Australian team, Sarah Heathcote, was working on the beam now. She was thirteen and only slightly taller than our girls, and not that much heavier. Spotting her, Markham headed back to his vantage point beside the apparatus, but not before giving me an odd kind of look. I wondered what rumours he might have heard. Then I reminded myself: what did it matter? All that mattered was that my gymnasts were more successful than any of their predecessors and I was recognised by the Romanian Gymnastics Organisation as the best coach of all time.

Which they would be. I would be.

It was almost a shame that Radu Constantin wouldn't be around to see it.

****

Arad, November 1974

'Here, Catalina, you can help me move the mats back tonight.'

I'm thrilled, so happy to be chosen. It's a sign that he likes me. Usually he selects Patrizia to help clear up at the end of the day. Patrizia is the best of us. She can already do the Korbut flip on the bars and she's only two years older than me, just twelve. There's talk of her leaving, going to the national training centre in Deva, maybe going to the next Olympics. I wish I could be as good. I'd give anything to be on the national team.

I help him move the mats back to their usual position, next to the row of beams. The mats are awkward more than heavy; it's hard for me to carry them with my short arms. When we've finished, he sits down on the lowest training beam, and pats it, signalling me to sit next to him.

'Thanks for helping me, Catalina,' he says.

'That's alright, sir.'

'You know, you're coming along well with your gymnastics.' He slips his arm around my waist. 'There's no reason why you shouldn't go all the way. Work hard, please me, and I'll recommend you for Deva.'

I feel so good inside. 'Thank you.'

He runs his fingers over my right leg. Then his hand moves between my thighs, rubbing gently. It feels sort of nice, but it's also strange and a bit scary and I don't know what to do.

He takes my hand and places it over his track suit pants. I can feel his willy twitching.

'I can help you achieve greatness in gymnastics, Catalina,' he says, moving my hand inside his pants. 'I can give you extra practice sessions, get you on the team. You just have to be a good girl and work hard.'

****

Arad, September 1991

I couldn't wait for the competition to be over and to see the back of the Australians. It was a nuisance having them around. I'd organised with the Romanian Gymnastics Organisation that the Australian gymnasts could train in the gym in the mornings as well as the afternoons. Our girls came in just for the afternoon. We told the Australians the girls were at school in the morning and had to go to bed early at night. At least that minimised contact between them.

It was still a long day for me though. Not only was it hard avoiding the Australians at meal times, but I was ravenous by the end of the day. On top of that, it was difficult coaching ordinary girls. I had no experience of that, and had to try to remember how Radu had coached us. Not that most of their gymnasts benefitted from excellent coaching - Rowena Harris had all the grace of a carthorse. Sarah Heathcote, though, she had real talent. She was better than the older Australians, but too young to compete at World or Olympic level. Poor girl; how disappointing to be from a country that wouldn't falsify her age. By the time she was old enough to compete in an Olympics, she'd be eighteen and probably past her best.

Sarah had refused to believe our girls were older than she was, given they were smaller. All the Australians struggled with this, pointing out age falsifications under the Communists. So at the end of the final day of training, I produced a video of Eugenia Sidon when she was ten, competing at a junior event with Nicolae Ceausescu watching.

'There,' I said. 'You can see that it's her. And that it was a long time ago. Ceausescu has been dead for nearly two years. This was taken well before the revolution.'

'She doesn't look any different,' commented the Australian coach, Marie Crago.

'She does - she's wearing a bigger hair ribbon on the video,' quipped Gary Markham.

'Melita Ungureanu's on this tape too, when she was eleven,' I said. I fast forwarded the grainy video, and there she was, twirling round the uneven bars. What a talented girl she'd been.

'Spot the difference - the hair ribbon,' joked Markham. 'Do all Romanian girls stay prepubescent forever?'

'No,' I said coldly. 'Look at me.'

'Don't most of them get really fat when they retire?' asked Rowena Harris. 'I've seen photos of when they finish gymnastics.'

'Some do,' said Nicolae Grecu, the president of the Romanian Gymnastics Organisation. 'But that will change. Under Communism, only elite athletes exercised. Now there are private gyms opening up, and there is better food in the shops.'

'I bet they eat everything in sight to make up for lost time and get fat that way,' said Marie Crago. 'We've been training with your girls for a week and we've never seen them eat.'

You wouldn't want to, I thought.

Rowena Harris commented that she'd never seen me eat either. I avoided responding by retrieving my video from the player. I excused myself and left them. I was ravenous. After all these years, I had amazing control, but really, hours and hours a day around ordinary people was too much.

I locked myself into a toilet stall and took a bottle of blood from my handbag. Slaking my thirst made me relax. The blood was rich and good. I had a steady supply from the hospital, though sometimes it didn't taste as good as others. This would fill a hole till I could go out properly later, with the girls.

When I went back into the gym, the Australians had gone to their hotel for dinner. My six gymnasts had opened their bottles of blood and were enjoying a long-overdue drink.

'Did Grecu leave as well?' I asked them.

'He's gone to the hotel for dinner, too,' said Eugenia. She took a flying leap across the floor to the uneven bars, swung around the higher bar then threw herself high above it turning three somersaults before catching it again. Beautiful as it was, this was something she wouldn't be able to do in competition or the world would become suspicious. I was careful to make sure that their routines were only just outside the realms of possibility.

'I'll give him time to eat dinner,' I said, 'then I'll go over and talk to him. We'll have to wait until later for supper, girls, I'm sorry. There are extra bottles in the fridge in the basement if you need them.'

****

The hotel that Grecu and the visitors were staying in was a few blocks away from the training centre. I knew I could make Grecu accede to my request that we did not accompany the Australians on the bus trip tomorrow. After a week of being stuck in our gym with ordinary people, I didn't want to have to spend another long day in their company. And I especially didn't want the girls to. They didn't have the many years' experience in control. We'd already had one nasty incident, when Melita Ungureanu lost control at a national meet some years ago. Fortunately, the Communists were still in power then, and it had been easy to make witnesses disappear.

The nine-storey hotel overlooked the river. Guests with river views were fortunate; the hotel had been built in the Ceausescu years and was grey, grim and depressing on the outside. It wasn't much better on the inside. Apparently the food was passable these days and there was hole-free linen on the beds.

Grecu was in his room on the fourth floor. He was watching television when I arrived. He'd been a gymnast himself and had competed in the Olympics before embarking on a career as a judge. Now, with the Communist era over and so many officials either disgraced or offered lucrative posts with wealthier foreign gymnastics organisations, he had risen to the top of the ladder. It was well beyond his level of competence, but he had me to help him achieve incredible results.

He argued a bit about the trip, but I only had to show him my fangs, and he backed down. Yes, of course, Catalina, he'd make apologies, whimper, whimper. I said good night and left him to his TV.

The lift had stopped working so I went into the stairwell and down the first flight of stairs when I caught the sound of someone crying. I stopped and tuned in.

'I have to get up early tomorrow. It's the competition. I'm supposed to get a good night's sleep.' It was a girl's voice. Tearful and young, with an Australian accent. Sarah Heathcote.

'Well, the quicker I get my good night kiss, the quicker you'll get to sleep.'

I knew that voice, too. Oh, yes.

I flung open the door of the stairwell and rushed along the corridor to the room with the voices. The lock on the door gave way when I pushed. There was Markham, sitting on the bed, one arm locked around Sarah. She looked flustered and tear-streaked.

'Get out,' I told him.

'I was just - '

'I know what you were doing. GET OUT!'

He didn't look at either of us as he left the room.

I told Sarah to wait for me while I dealt with Markham. I grabbed him in the corridor and pushed him into the stairwell. 'You're coming with me.'

Once we were outside I moved so fast that no-one could have seen us. We were at the training centre in seconds. He was shaking and nauseous when I dropped him on the sprung floor exercise area of the gym.

The girls were waiting for me, as hungry as I was. By now we would usually have been to the prison where we fed nightly. Only a few short years ago there'd been political prisoners to feed on, but now we had to live off the blood of murderers and rapists. I'd go to the prison for my meal later. Markham was for the girls.

It must have felt like a dream come true for him, when Eugenia and Melita approached him and pushed him down to the ground. But terror flooded his eyes when their fangs slid out and he realised he was going to die. It reminded me of the night I'd killed Radu.

****

Arad, September 1984

'You have brought all this trouble on us, Danut.'

My grandmother was feverish and agitated as she sat up in bed. I tried to spoon-feed her some soup. My father had just come in to tell us that he couldn't get the doctor to visit her. She was old, dying, and Father had been told that there was no medicine that would cure her. It had been the same since that night in 1977, when my mother had found bruises all over my body. I'd been having private 'training sessions' for three years with Radu then. I was on the national junior squad, and he'd recommended me for Deva. This had made me bold and I'd refused to give him oral sex. When I finally told my mother, my father had gone crazy. He'd gone to the gym the next day and beaten Radu.

And that was it. I was finished in gymnastics. My parents didn't want me in Radu's gym but no other would take me. Not Deva. I was one of hundreds of talented girls. Romanian gymnastics didn't need me. I was flung off the national team. I went back to school full-time, but only got poor marks no matter how hard I tried. When I left, I could only get a job in a factory.

We suffered in other ways too. My father never got promoted at work. We never moved up the waiting list for a car. And now there was no medicine for Grandmother.

'What would you have done?' my father demanded now. 'Let that animal continue to abuse her so that our family wouldn't be harassed by the authorities?'

'I'm not talking about that,' she replied. 'I'm talking about Petru and you know it. Our family was in thrall to him for centuries and you - 'She paused to cough and began sweating again. I offered water but she waved the glass away. 'You refused.'

'What are you talking about?' I asked. 'Who's Petru?'

'Ignore her. She's feverish,' my father said.

'It's only because of the Communists that he's left you alone,' Grandmother said, glaring at my father. 'You should have let him take your blood -things went much better for our family when we did what Petru wanted.'

'Let her rest, Catalina,' Father said, leaving the room. When the door closed, she grabbed my arm and looked right into my eyes. 'Go to the old church in the forest,' she whispered, 'Find Petru yourself.'

Two weeks after we buried my grandmother I took the track that she'd described through the forest. At first I thought the squat wooden building was an abandoned barn. A few panels had been kicked in and it was only the white cross painted on the weather-beaten roof that confirmed that it really was a church. There was wire fencing around it, perhaps intended to prevent further vandalism, but I climbed over it easily. I knocked seven times on the door.

When he opened the door, I wanted to run away. He was so tall. Taller than any man I'd ever met. His white skin and long fangs were terrifying. I didn't know how to begin to speak to him, but he guessed who I was and my purpose.

He wasn't curious about what was in it for me. Perhaps he guessed, or maybe he just didn't care. Petru took my blood and I drank his. It was disgusting, but I knew it was worth it to get what I wanted.

Afterwards, I went down to the training centre and found Radu alone in the gym. Hatred swelled inside me for the way he'd abused me and wrecked my life. I grabbed him and twisted his dick until he screamed. I felt satisfied as I watch him writhe and plunged my fangs into his neck, draining him of blood and life.

I took over his gym. With my help and Petru's, my talented young juniors, driven to do anything to get on the national team, would win the Olympics. Their bodies would remain forever prepubescent and capable of executing unimaginable skills.

****

Arad, September 1991

Sarah was still in her room. She was sitting up on the bed, staring uncomprehendingly at the television.

'You don't have to worry about Markham again,' I said, putting an arm around her. 'He won't bother you anymore.'

'He was a teacher at my school,' she said. 'I was there on a scholarship because of my gymnastics. He said if I didn't do what he wanted, he'd make sure I lost the scholarship. Without that, my parents couldn't afford to send me. When he left and I thought it was all over. But now he's always at gym meets, always…' Her voice trailed off.

'He won't bother you again. He's dead.'

'Are all the Romanian gymnasts vampires? Is that why they're so good at gymnastics and so small and why they don't eat food at all and why they never smile?'

She'd likely seen my fangs when I got angry with Markham; they'd probably slid out and she'd guessed about the girls. Oh, shit, I thought. Oh, shit, shit, shit. I didn't want to have to kill her. She had talent. And I'd just killed her abuser. But she knew and we couldn't afford the truth getting out.

'I want to be like you' she told me. 'I want to win gold for Australia. I'd do anything to be the best.'

I thought about it. There was no reason why, in this new era of friendship, I couldn't train a talented Australian junior. She offered me her neck.

My own girls would face some unexpectedly tough competition tomorrow.