Читать книгу The Pink Ghetto - Liz Ireland - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеAfter all that’s happened, most of the people think it was that book that changed everything for me. It’s not hard to understand why. I blamed everything on the book at first, too. I was bitter, I’ll admit that. In my shoes, anyone would have been.

But recently, thanks to the support of my friends, my family, and the personal growth section at Barnes and Noble, I’ve adopted a more zenlike attitude toward the whole episode. To put it in a string of clichés: I am bowed but not broken. That which did not kill me has made me stronger. I have washed that man right out of my hair.

Taking the longer view, I can see that it wasn’t heartbreak or even that book that altered my life. Not really. It was the job. The job changed everything, which is weird, because at the time I was so desperate to earn money that I didn’t even pay attention to what I was applying for.

The ad didn’t name the company. Lodged as it was in the middle of the employment section of the New York Times without a box or even much bold lettering, it seemed anonymous, non-threatening, almost forgettable. A little brown bag of an ad. Well-known publishing house seeks assistant editor, it said. Or something to that effect.

Well-known publishing house. Lurking behind those four innocent words was a whole new world, amazing to the uninitiated and fraught with unseen traps that a novice was bound to step in, like those pits camouflaged by leaves in an old Abbott and Costello jungle movie.

I didn’t realize it myself for months, until I was sprawled on the ground, shaking the banana leaves out of my hair.

Not that it would have mattered at the time when I spotted the ad. Like I said, I was desperate. If Pol Pot had been hiring, I probably would have fired off my resume. I was sending out that document, so heavily padded that it could have played tackle in the NFL, to any and every business that sounded as though they required a semiliterate being to park at a desk all day. In a blizzard of cover letters blanketing the human resources departments of Manhattan that month, I professed my profound desire to be a proofreader, executive assistant, editorial assistant, or any type of flunky imaginable sought by the worlds of advertising, public relations, or broadcasting. I needed a job, and the sooner the better.

For two and a half unbelievable years I had been living on easy street. Actually, the address was a floor-through in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, land of the trust fund bohemian. I had no trust fund, but I had been incomparably lucky since getting out of college, when, through a professor, I had landed a position as a personal assistant to Sylvie Arnaud.

Sylvie Arnaud was one of those people that the early Twentieth Century popped out now and then—magic people who were simply famous for being around all the right people.

How she had become famous, no one remembered. Perhaps sometime circa 1935 she had written something, or painted something, or slept with someone who had written or painted something. Her name would occasionally pop up in The New York Review of Books, during the course of a discussion of a review of books about German Expressionist painters, say. She knew everybody. Ernest Hemingway. Salvador Dali. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Harpo Marx. You can play a highbrow Where’s Waldo? with her in pictures of intellectuals and rich folk gathered in salons in Paris and London between the wars. Chances are she’ll be there somewhere, maybe sitting next to Cole Porter and looking impossibly elegant in her slinky bias cut dresses, with a drink in one hand and a stretch limousine cigarette holder in the other.

By the time I knew her, she was a beaky, wizened old creature on toothpick legs, with jaundiced flesh as thin as onion skin parchment. She lived in a dark, musty brownstone on the Upper East Side, in Turtle Bay. When my old college professor who helped get me the job told me about the position, he said that I would probably be helping her assemble her personal papers so she could write her autobiography. But I was not taking down her memoirs; instead, I spent most of my time chasing after her favorite groceries, like these nasty chocolate covered apricot filled cookies that she practically lived on. Believe me, I am not picky when it comes to food. There’s nothing I can’t deem binge-worthy if I stare at it long enough, but even I would make an exception for those cookies.

And her peculiarities didn’t end there. She also liked a specific kind of hot pickled okra that could only be found in Harlem; butter mints from the basement at Macy’s; baguettes and croissants from a French bakery in Brooklyn Heights. She preferred cloth hankies to Kleenex and Lava soap to the expensive kind I bought her once on her birthday, and woebetide the person who made the mistake of serving her ice in her drinks.

She was one peculiar old lady.

She didn’t talk to me much about Picasso, or Earnest Hemingway, or the Duchess of Windsor. I arrived too late for that. Mostly I heard about her ingrown toenails and her skin problems. I guess when you’re ninety-four and you itch, dead painter friends become a second tier concern.

When I first started working for her I would bring up the subject of her memoirs.

“What are these memoirs you are always pestering me about, Rebecca?” She had a trace of her native accent, but it was an off-and-on thing. She could lay it on thick if she wanted, turning these to zeez.

I tried not to let on that I was disappointed not to be doing important literary work. “I just thought…if you needed any help going through your journals…”

She would laugh throatily at that idea. “Ah, you see me as some sort of crazy old artifact, non?”

“No, no,” I would stutter. (A lie. I did.)

“Naturally! You want to know all my little secrets, like whether Cary Grant was good in bed.”

“No, I…” I gulped. “Wait. Cary Grant?”

She would bark with glee at me, tell me to take her laundry down to the basement, and then ignore me for the rest of the afternoon. I began to suspect the diaries didn’t exist anyway. Maybe she’d never been any closer to Cary Grant than I had been.

Or maybe she had.

Occasionally an academic would make his way to the brownstone, but he always left disappointed. He might sit in a chair with a plate of those apricot cookies and listen to Sylvie rave for a few minutes about John-Paul Sartre’s bad breath; generally it didn’t take much longer to realize that Sylvie wasn’t going to divulge much useful information. Even though Sylvie had been living in New York since the sixties, her principal visitors while I was there were not glitterati or even academics, but a physical therapist named Chuck and an old lady from the Bronx named Bernadine.

Sylvie was a mystery to me, right down to the question of what I was doing there. I couldn’t figure out why she wanted to pay even my nominal salary to have me around. I couldn’t even figure out why this old French lady was in New York.

Then again, I didn’t waste a lot of time worrying about it. When I began working for her I was twenty-two and it was the first time I’d ever lived in New York City, so I wasn’t exactly consumed with curiosity about my nonagenarian employer.

And I had nothing to complain about. On the first day of every month a check arrived from the manager of Sylvie’s estate, R.J. Langley, CPA, which made me the prime breadwinner among my roommates in our apartment in Williamsburg. At the time I was too young to appreciate that getting paid a living wage for buying an old lady’s baguettes was really nothing short of a miracle.

Then one morning as I was getting ready to hie myself off to Manhattan, I received a call from R.J. Langley, the first time I had ever spoken to the man personally. He asked me—commanded me, actually—to go to his office in midtown first thing.

“Why?” I asked. “Is something wrong?”

“Actually, yes. I have bad news. Miss Arnaud has pneumonia.”

“Oh, no! What hospital?”

There was a pause. “I can give you more details in person.”

During the subway ride over, I was filled with sadness. Poor Sylvie, stuck in the hospital, eating Jell-O. She hated being away from her apartment, away from all her musty old crap. I made out a mental list of her favorite things I could put into a hospital care package for her.

When I arrived at the accountant’s office, however, I was hit by a real shocker. Mr. Langley pushed an envelope across the vast oaken plateau that was his desk. “We would like to thank you for your service to Miss Arnaud.”

I gawped at the check, which was for twice the amount I usually received.

“That’s for your last weeks of work, plus two weeks severance,” Langley said. “I’m afraid we have to let you go.”

He kept saying we. “But what about Sylvie?”

“If she recovers—”

“If!” I bleated.

He winced at my outburst. “Miss Arnaud is at a very advanced age, as you know, and her condition is serious. If she survives, it is her wish and the wish of her beneficiaries that she be moved to an assisted living community. You must understand.”

I did not. And who were these beneficiaries? They had certainly not visited her while I had been there.

“I’d like to see Sylvie.”

The wrinkles of studied concern that had creased his brow disappeared. “I don’t think that will be necessary, or even advisable considering her present condition.”

Growing miffed, I asked, “Will you at least tell me where she is?”

“I will take that up with the beneficiaries.”

I stood up, filled with righteous anger. I had a feeling I was talking to the primary beneficiary. Maybe the only one. The weasel. “Fine. Please ask them, Mr. Langley. Please assure the beneficiaries that all I want to do is bring Miss Arnaud a box of her favorite cookies.”

I sailed out of his office, my indignation at full mast.

Needless to say, I never got a call telling me Sylvie’s whereabouts. But to be honest, I didn’t knock myself out trying to find her on my own. I didn’t work at it at all. When it came down to it, I rationalized, I had just been Sylvie’s employee. She wasn’t my responsibility. And if her heirs worried that I would somehow winnow my way into her will, then fine. Let them comb the island of Manhattan for butter mints and hot pickled okra.

It didn’t take long for my severance money to dry up, and no one came forward offering me another cushy job. One of my roommates, an aspiring playwright named Fleishman, was working sporadically at a part-time job with a telemarketing company selling vinyl siding one day and ballet subscriptions the next. My other roommate, Wendy, was studying lighting design at NYU and honing her barista skills at Starbucks. We had known each other since college. We were the three musketeers, but without my paycheck, we were more like three shipwrecked souls on a leaky lifeboat.

Wendy was somewhat worried, but she was too busy to do much to solve our financial conundrum.

Fleishman was not worried, because he never worried, especially about money. He came from serious money—he was a descendent of an established chain of discount shoe store owners. He himself had no interest in shoes (at least not the discount variety), and since his parents did not consider playwriting a good use of their son’s life, at the moment he was supposed to be cut off from the family. His mother, however, would occasionally suffer a wave of maternal guilt and come into the city to take Fleishman out to lunch (and take in the stores, no doubt.) On these days, Fleishman would return to our apartment with a wad of cash in his pockets. Or maybe sporting a new leather jacket. Christmas and birthdays—even in his disinherited state—tended to be accompanied by a thin envelope bearing a fat check. Broke was always a temporary thing to Fleishman. He always had hope.

My dad owned a plumbing supply business, which, while lucrative, did not provide for periodic windfalls. I was the fifth of six kids. My parents bankrolled me through college with the tacit understanding that afterwards I was to be completely on my own. My dad, in his usual self-effacing way, called this kind of generosity paying for the privilege of getting rid of me. Given that they still had my little brother in college, and now grandchildren to juggle, I would have died before I asked them for more money.

In February, my roommates and I were one hundred and forty dollars short on the rent, so I sold my notebook computer on eBay. This was a psychological low-water mark. Not that I actually needed my notebook. When I had come to New York, I had thought I would write something. Sylvie’s memoirs. Maybe short stories; I had done a few of those in college. It had been two years, though, and I hadn’t written anything more taxing than a grocery list.

Unfortunately, my notebook was my only valuable. I couldn’t hock anymore even if I’d wanted to. I needed a job. Fast.

Out flew the resumes. But the expected responses never came pouring in. After three weeks, I’d had exactly two interviews, neither of which had borne fruit. The calendar advanced relentlessly toward the next rent due date. It was nail biting time. So when my phone rang and the person on the other end of the line said she was calling from Candlelight Books and that I had an interview, it felt like a lifeline was being thrown at me. I was ecstatic.

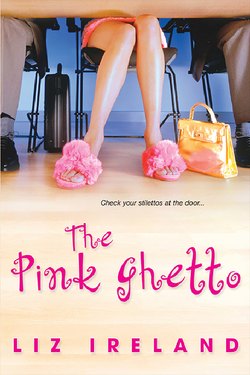

I knew what Candlelight Books was, of course. Who didn’t? They were the colossus of romance, the books everyone’s aunts read but that they never read themselves. You couldn’t walk through a superstore in the heartland or a drugstore anywhere without seeing racks of them, all branded with the flickering candle logo.

I just didn’t remember applying there. Not that I was about to tell that to the woman on the telephone. I wasn’t about to say anything that might risk my chances for getting my foot in the door. She instructed me to appear at the offices on the following day at one o’clock, and I assured her I would be there.

“What’s the job?” Fleishman asked when he saw me dragging my interview suit out of our closet.

A railroad flat is not an ideal setup for communal living. The apartment took up an entire floor of a rowhouse, and there were three rooms, sort of (one had surely been meant to be a hall, or a dining area), but there were no doors between the rooms. It was just one long breezeway. In other words, for having blowout parties or as a roller rink, the place would have been ideal. For trying to section off three bedrooms, it was a challenge. We all had to share the one closet, which during the residency of some previous tenant had lost its sliding door and now was “closed” with a shower curtain with a tropical fish motif.

“It’s with Candlelight Books.”

Fleishman barked out a laugh. “You are kidding me. You’re going to work on romance novels? You? You’ve never had a successful romance in your life.”

I didn’t really need to be reminded of that. Especially since one of my failed romances was with him.

“They aren’t looking for Masters and Johnson,” I said.

“Good.”

I eyed him sharply. I admit it—I could still be a little defensive when it came to our relationship. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Nothing,” he said, rolling his eyes. He always complained that I was too sensitive. “I’m amazed you applied there, though.”

“I didn’t even know I had. The ad didn’t give the name of the company.”

“They were probably afraid that people wouldn’t answer the ad if they knew it was for Candlelight Books.”

“Probably.” No doubt there were some people who would turn up their noses at working around romance novels. I was not one of those people. Correction: Since having to auction my belongings on eBay, I had ceased to be one of those people.

“I think you’d make a great editor.”

“I think it’s just secretarial. Or something.”

He raised his brows. Fleishman had very distinctive, Dracula-like brows, so it always seemed very dramatic when they arched at you. “You don’t know?”

“I’m sure it’s an editorial assistant job.” I was fairly certain I had applied for a few of those. Not that I had any idea what an editorial assistant actually did. “Or assistant something-or-other. I answered so many ads…”

I once read in a book about job hunting that you should keep a tidy folder documenting all the places you’ve applied, and listing all the relevant dates for callbacks and interviews. But if I had been that organized in the first place, I probably wouldn’t be the kind of putz who was scrabbling for a job, any job.

Now Wendy, she would have made a folder. Wendy was that way. She kept a chart on our refrigerator to keep track of whose week it was to take out the garbage.

Fleishman was more like me. (Which made it extra fortunate that we had Wendy.) “Well, whatever,” he said. “Once you have a bundle saved from your lucrative new career, you can produce Yule Be Sorry.”

“Don’t hold your breath.” I quickly added, “The position’s not that lucrative.”

But what I really meant was, fat chance I would ever help Yule Be Sorry see the light of day.

Yule Be Sorry was Fleishman’s latest unfinished theatrical masterpiece, dreamed up after he had spent Christmas with my family in Cleveland. Fleishman’s plays, which had made him the Noel Coward of our little college, were airy, funny pieces with just enough message to justify their being written at all. Yule Be Sorry continued in this tradition. But even in the one act he had written, the thinly disguised picture of my family was not pretty—the Alberts came off as a collection of airheads and rubes. And the girl protagonist of the play, the one who brings her ex-boyfriend home for the holiday—in other words, me—was especially grating. She had a few good lines, but for the most part she was a scold, a former fat girl who secretly scarfed down spritz cookies when no one was looking.

Okay, maybe that last part was me spot-on, but come on. Was I a scold? I didn’t think so. Yes, I was just more practical than Fleishman, but that was setting the bar so low the midgets of the Lollypop Guild couldn’t have limboed under it. Anna Nicole Smith was probably more practical than Fleishman.

This play would have weighed more heavily on my mind if I had thought that Fleishman would ever finish his masterpiece. But he had been completely unproductive since graduation. What really went over big in a small school in Ohio was not exactly what the Great White Way was clamoring for. I could sense Fleishman getting discouraged. He hadn’t written much of anything in the past year, and he had lost that glow of the big-fish-in-a-small-pond celebrity he had when we first met. Lately it seemed that he mostly misspent his nights drinking too much cheap wine and watching Green Acres.

Nobody tells you this growing up, but the reason you’re supposed to develop good work habits is so when the academic world spits you out at the age of twenty-two, your personal ambitions won’t be sidelined by the seductive lure of TV Land.

Fleishman squinted in despair at my gray interview suit, which had been a college graduation present from my mom. I had never had to use it until that month. “You think that’s the right outfit for this job interview?”

I furrowed my brow. During the last interview, I had splooped coffee on the jacket and I hadn’t been able to get it out with a Shout wipe. “Why not?”

“Because that suit is not the right suit for any job interview.”

I couldn’t argue. The suit was pretty much ugly all day: a slate gray color that would wash out even the most Coppertoned skin, a Mao collared jacket that made my bust look like one vast gray rolling plain, and a skirt with a hem that hit at mid kneecap, which was a flattering length on no one.

“Plus I imagine people at Candlelight Books all run around the offices in pink sequins and feather boas,” Fleishman said.

“It’s a business,” I replied. “The woman on the phone sounded very businesslike.”

“Right. It’s probably just the authors who run around all day in lounging pajamas.” He flopped onto the couch. “I hope you get this job! It’ll be so entertaining to hear you talk about. You’ll get to talk to people like what’s her name.”

“Who?”

He snapped his fingers. “You know—that one who’s on the bestseller lists all the time.”

“I have no idea who you’re talking about.”

Neither did he.

“It’s probably just some flunky job. I might just answer phones or something.”

“You’re always downpeddling,” he said. “What if this is actually the beginning of something big?”

He flashed those gray eyes of his in a way that, I admit it, could still make my insides go fluttery. Which was amazing, considering all we’d been through. I mean, we’d been friends, and—briefly—lovers, and endured a breakup, and then become roommates. One New Year’s after we’d just moved to New York, we had re-succumbed to each other, but now our romance was officially in full remission. I’d watched him date other women. Worse, I’d watched him floss his teeth in front of the eleven o’clock news. That alone should have squelched any residual fluttering, but no such luck.

I shook my head. “Big, as in…?”

“Think of it. We’ve both been knocking around this city for almost three years now. It’s time one of us got a break, isn’t it?”

“In other words, you think I’m going to go to that interview a youngster, but I have to come back a star?”

“Don’t be so cynical. This could be a really great career turn for you.”

Could it? I tried to stay guarded. Sometimes Fleishman exuded this crazy enthusiasm that could carry me aloft. He could go nuts over an idea, or some wacky plan, or even a new Web site he’d found. It’s part of why I found him so appealing. He could pull enthusiasm out of thin air and toss it over me like fairy dust. A little of it was twinkling over me now.