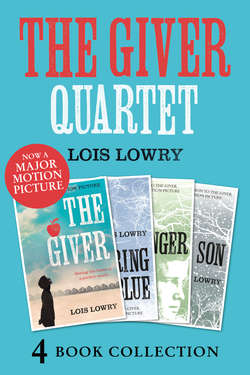

Читать книгу The Giver, Gathering Blue, Messenger, Son - Lois Lowry, Lois Lowry - Страница 30

Оглавление

IT WOULD WORK. They could make it work, Jonas told himself again and again throughout the day.

But that evening everything changed. All of it – all the things they had thought through so meticulously – fell apart.

That night, Jonas was forced to flee. He left the dwelling shortly after the sky became dark and the community still. It was terribly dangerous because some of the work crews were still about, but he moved stealthily and silently, staying in the shadows, making his way past the darkened dwellings and the empty Central Plaza, towards the river. Beyond the Plaza he could see the House of the Old, with the Annexe behind it, outlined against the night sky. But he could not stop there. There was no time. Every minute counted now, and every minute must take him farther from the community.

Now he was on the bridge, hunched over on the bicycle, pedalling steadily. He could see the dark, churning water far below.

He felt, surprisingly, no fear, nor any regret at leaving the community behind. But he felt a very deep sadness that he had left his closest friend behind. He knew that in the danger of his escape he must be absolutely silent; but with his heart and mind, he called back and hoped that with his capacity for hearing-beyond, the Giver would know that Jonas had said goodbye.

It had happened at the evening meal. The family unit was eating together as always: Lily chattering away, Mother and Father making their customary comments (and lies, Jonas knew) about the day. Nearby, Gabriel played happily on the floor, babbling his baby talk, looking with glee now and then towards Jonas, obviously delighted to have him back after the unexpected night away from the dwelling.

Father glanced down towards the toddler. “Enjoy it, little guy,” he said. “This is your last night as visitor.”

“What do you mean?” Jonas asked him.

Father sighed with disappointment. “Well, you know he wasn’t here when you got home this morning because we had him stay overnight at the Nurturing Centre. It seemed like a good opportunity, with you gone, to give it a try. He’d been sleeping so soundly.”

“Didn’t it go well?” Mother asked sympathetically.

Father gave a rueful laugh. “That’s an understatement. It was a disaster. He cried all night, apparently. The night crew couldn’t handle it. They were really frazzled by the time I got to work.”

“Gabe, you naughty thing,” Lily said, with a scolding little cluck towards the grinning toddler on the floor.

“So,” Father went on, “we obviously had to make the decision. Even I voted for Gabriel’s release when we had the meeting this afternoon.”

Jonas put down his fork and stared at his father. “Release?” he asked.

Father nodded. “We certainly gave it our best try, didn’t we?”

“Yes, we did,” Mother agreed emphatically.

Lily nodded in agreement, too.

Jonas worked at keeping his voice absolutely calm. “When?” he asked. “When will he be released?”

“First thing tomorrow morning. We have to start our preparations for the Naming Ceremony, so we thought we’d get this taken care of right away.

“It’s bye-bye to you, Gabe, in the morning,” Father had said, in his sweet, sing-song voice.

Jonas reached the opposite side of the river, stopped briefly, and looked back. The community where his entire life had been lived lay behind him now, sleeping. At dawn, the orderly, disciplined life he had always known would continue again, without him. The life where nothing was ever unexpected. Or inconvenient. Or unusual. The life without colour, pain or past.

He pushed firmly again at the pedal with his foot and continued riding along the road. It was not safe to spend time looking back. He thought of the rules he had broken so far: enough that if he were caught, now, he would be condemned.

First, he had left the dwelling at night. A major transgression.

Second, he had robbed the community of food: a very serious crime, even though what he had taken was leftovers, set out on the dwelling doorsteps for collection.

Third, he had stolen his father’s bicycle. He had hesitated for a moment, standing beside the bikeport in the darkness, not wanting anything of his father’s and uncertain, as well, whether he could comfortably ride the larger bike when he was so accustomed to his own.

But it was necessary because it had the child seat attached to the back.

And he had taken Gabriel, too.

He could feel the little head nudge his back, bouncing gently against him as he rode. Gabriel was sleeping soundly, strapped into the seat. Before he had left the dwelling, he had laid his hands firmly on Gabe’s back and transmitted to him the most soothing memory he could: a slow-swinging hammock under palm trees on an island somewhere, at evening, with a rhythmic sound of languid water lapping hypnotically against a beach nearby. As the memory seeped from him into the newchild, he could feel Gabe’s sleep ease and deepen. There had been no stir at all when Jonas lifted him from the crib and placed him gently into the moulded seat.

He knew that he had the remaining hours of night before they would be aware of his escape. So he rode hard, steadily, willing himself not to tire as the minutes and miles passed. There had been no time to receive the memories he and the Giver had counted on, of strength and courage. So he relied on what he had, and hoped it would be enough.

He circled the outlying communities, their dwellings dark. Gradually the distances between communities widened, with longer stretches of empty road. His legs ached at first; then, as time passed, they became numb.

At dawn Gabriel began to stir. They were in an isolated place; fields on either side of the road were dotted with thickets of trees here and there. He saw a stream, and made his way to it across a rutted, bumpy meadow; Gabriel, wide awake now, giggled as the bicycle jolted him up and down.

Jonas unstrapped Gabe, lifted him from the bike, and watched him investigate the grass and twigs with delight. Carefully he hid the bicycle in thick bushes.

“Morning meal, Gabe!” He unwrapped some of the food and fed them both. Then he filled the cup he had brought with water from the stream and held it for Gabriel to drink. He drank thirstily himself, and sat by the stream, watching the newchild play.

He was exhausted. He knew he must sleep, resting his own muscles and preparing himself for more hours on the bicycle. It would not be safe to travel in daylight.

They would be looking for him soon.

He found a place deeply hidden in the trees, took the newchild there, and lay down, holding Gabriel in his arms. Gabe struggled cheerfully as if it were a wrestling game, the kind they had played back in the dwelling, with tickles and laughter.

“Sorry, Gabe,” Jonas told him. “I know it’s morning, and I know you’ve just woken up. But we have to sleep now.”

He cuddled the small body close to him, and rubbed the little back. He murmured to Gabriel soothingly. Then he pressed his hands firmly and transmitted a memory of deep, contented exhaustion. Gabriel’s head nodded, after a moment, and fell against Jonas’s chest.

Together the fugitives slept through the first dangerous day.

The most terrifying thing was the planes. By now, days had passed; Jonas no longer knew how many. The journey had become automatic: the sleep by days, hidden in underbrush and trees; the finding of water; the careful division of scraps of food, augmented by what he could find in the fields. And the endless, endless miles on the bicycle by night.

His leg muscles were taut now. They ached when he settled himself to sleep. But they were stronger, and he stopped now less often to rest. Sometimes he paused and lifted Gabriel down for a brief bit of exercise, running down the road or through a field together in the dark. But always, when he returned, strapped the uncomplaining toddler into the seat again and remounted, his legs were ready.

So he had enough strength of his own, and had not needed what the Giver might have provided, had there been time.

But when the planes came, he wished that he could have received the courage.

He knew they were search planes. They flew so low that they woke him with the noise of their engines, and sometimes, looking out and up fearfully from the hiding places, he could almost see the faces of the searchers.

He knew that they could not see colour, and that their flesh, as well as Gabriel’s light golden curls, would be no more than smears of grey against the colourless foliage. But he remembered from his science and technology studies at school that the search planes used heat-seeking devices which could identify body warmth and would hone in on two humans huddled in shrubbery.

So always, when he heard the aircraft sound, he reached to Gabriel and transmitted memories of snow, keeping some for himself. Together they became cold; and when the planes were gone, they would shiver, holding each other, until sleep came again.

Sometimes, urging the memories into Gabriel, Jonas felt that they were more shallow, a little weaker than they had been. It was what he had hoped, and what he and the Giver had planned: that as he moved away from the community, he would shed the memories and leave them behind for the people. But now, when he needed them, when the planes came, he tried hard to cling to what he still had, of cold, and to use it for their survival.

Usually the aircraft came by day, when they were hiding. But he was alert at night, too, on the road, always listening intently for the sound of the engines. Even Gabriel listened, and would call out, “Plane! Plane!” sometimes before Jonas had heard the terrifying noise. When the aircraft searchers came, as they did occasionally, during the night as they rode, Jonas sped to the nearest tree or bush, dropped to the ground, and made himself and Gabriel cold. But it was sometimes a frighteningly close call.

As he pedalled through the nights, through isolated landscape now, with the communities far behind and no sign of human habitation around him or ahead, he was constantly vigilant, looking for the next nearest hiding place should the sound of engines come.

But the frequency of the planes diminished. They came less often, and flew, when they did come, less slowly, as if the search had become haphazard and no longer hopeful. Finally there was an entire day and night when they did not come at all.