Читать книгу Romanticism - Léon Rosenthal - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

III. The Romantic Inspiration

ОглавлениеWas the movement that we have just described only a violent bout of fever? Was it anything more than exaggeration and distortion? Did it only have a superficial and, when all is said and done, perhaps regrettable influence on artists? Was it going to be remembered as a movement marked by a strong and rampant taste for trinkets, cheap rubbish and mundane anecdotes, a movement mostly interested in subjects taken from fiction or history and easy to turn into vivid scenes? Those subjects corresponded to the fashion of the time, and if Romanticism had been limited to illustrating books and popular historical stories it would then be difficult to understand why it faced such strong resistance. If it was only made of mannerism and failings would it have kept raising so much passion and would it have remained polemical a century later?

Romanticism actually marked a general change of minds. As mentioned at the beginning of this book, it had expressed itself in all areas of human thinking and in all activities; it had had a deep impact on the arts. The works that it had influenced were linked together not just by superficial analogy but were closely related. They had been created according to the same norms and had used similar methods. It is those norms and methods that we are now going to try to unveil.

A Romantic person was first of all sensitive and someone on whom logic and pure ideas had little impact. It was a knowledgeable person whose actions were based on intuition: as a statesman, he would obey a generous or imaginary impetus; as a writer or poet his thinking was taking shape in images. All the more so for artists, who had no interest in abstraction but were indeed visionary. Others tried to draw a perfect type, a pure ideal beauty out of the diversity of humankind, but the Romantic, on the contrary, saw vivid creatures, all different and all touching in some way. He would develop friendships with certain individuals but was never exclusive and, in fact, was ready to change as he feared monotony more than anything else. In turn he would be interested in hook-nosed, pug-nosed, turned up-nosed people, slim or stocky types. He was seduced by unexpected appearances: irregular faces, deformities, alterations caused by illnesses and age. He was accused of cherishing ugliness whilst looking for character above all. Nature provided him with an infinite diversity of individuals and he could not see Apollo anywhere. If, by a miracle, Apollo were to spring up in front of his eyes, he would not represent the god in a fixed eternal attitude but would show him changing all the time, always different from himself because of the miracle of life. The classical man ignored it or, at least, always tried to fight against it whilst the Romantic observed it with pleasure and saw the source of beauty in it. The lines and volumes that the classicist aspired to give balance to according to blind geometry were perceived by the Romantics as a sacred interaction of internal forces. Flesh quivered, blood ran, muscles tensed. Man was a magnificent machine: his shapes were not abstract calligraphy but they expressed the workings of physiological life. Catching life in action and movement before it was finished, observing the short instants when, guided by passion and under the pressure of dramatic circumstances, life reached a paroxysm, avoiding what pretended to be constant and celebrating the transitory and short-lived in life: these were the joys of the artist.

In studios, models would wrap themselves in indifferent clothes with more or less harmonious folds. Man would dress according to the climate he lived in, his needs and his tastes; his dressing style would reflect his personality and participate in his restlessness and existence itself.

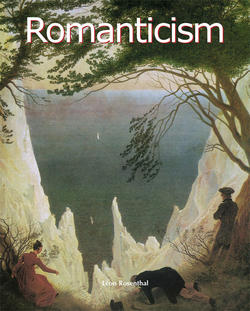

To finish, man was not an isolated creature in the middle of a silent world. Life was all around him. Animals ran, flew or crawled, being moved (like humans) by a subtle system of forces. There were tangible affinities between man and animals. Less complex by nature, they provided the eye with sights which man could not rival. Nature was not an empty architectural structure, mere décor or background. It was full of elementary beings, close to us, visible or invisible, and even the things in it were constantly changing. The landscapes that seemed most stable were continually changing with leaves trembling in the wind, birds singing, light changing. It was a source of endless and renewed wonder. Inhabited by all those lives, nature itself seemed alive. One might consider it a form of pantheism except that the Romantics did not care about philosophical concepts so much. They only knew that their feelings and thoughts expanded in forests, at the seaside, or in mountains: if they were tormented, their restlessness calmed down. They were thankful to nature for that soothing action. Unlike poets who revolted against it because it did not echo their love experiences, Romantic artists paid tribute to the maternal and consoling quality of nature.

Though their universal sympathy went out in many directions, Romantic artists were in fact looking for themselves and, through their prodigal love for so many things and beings, they actually cherished themselves. Their curiosity was eager because their souls had an inextinguishable need of feeding. They never watched anything with dispassionate eyes, simply for the pleasure of knowledge: they would never forget themselves. One did not expect scientific testimony from any of them. They liked truth and wanted to be sincere, but their subjectivity and lyricism could not help but distort reality.

If he happened to be a man of rare genius, endowed with a whole set of exceptional and superior qualities that enabled him to think, suffer and be thrilled more than other mediocre human beings, the Romantic artist put fervent passion into his work as well as a taste for dramatisation and, in the early years of Romanticism, a dark mood which would get lighter with time but without ever reaching actual joyfulness. Even if he was a powerful worker merely admired for his skills, like Decamps or Barye, the complexity of his expressive moods and sometimes the surfeit and subtlety of details would be enough to prove that he belonged to a tormented generation.

Before starting a painting, Delacroix gathered information carefully, but once he had started work he could not bear the presence of models who put him off. The repulsion that he felt for his time is a more surprising paradox. The Flemish and Venetian artists whose influence he claimed, Véronèse and Rubens, had magnified the human beings and things around them. Not only did they take pleasure in their art, they thrived on the spirit of beauty in which they lived. They cherished their times and surroundings, in which they found allegory, history and religion. But the Romantic man felt ill at ease in his century: life in his time was dull, monuments were ugly and clothes shapeless. The crowd was merely eager for vulgar pleasures. Artists were isolated because they were different and misunderstood by their contemporaries. An object of vain ridicule early in life, these deplorable sentiments solidified through the trials of sarcasm and persecution throughout an artist’s career.

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from The Bishop’s Ground, 1823.

Oil on canvas, 87.6 × 111.8 cm.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу