Читать книгу Two Bottles of Relish: The Little Tales of Smethers and Other Stories - Lord Dunsany, Lord Dunsany - Страница 9

THE SECOND FRONT

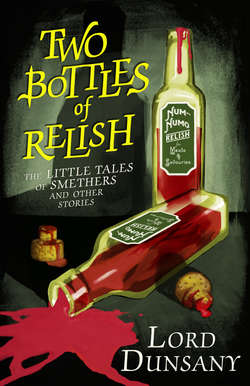

ОглавлениеIT’S some time now since I wrote about Mr Linley, and I don’t suppose anyone remembers the name of Smethers. That’s my name. But the whole world knows Numnumo, the relish for meats and savouries; and I push it. That is to say I travel and I take orders for it, or I used to, before this war upset everything. And some may remember the tale I wrote about that, about Numnumo I mean, because Mr Linley came into it, and he’s a man you don’t forget so easily; and, if you do, perhaps you don’t forget Steeger and what happened at Unge. Horrid it was. I told about that in my story: The Two Bottles of Relish I called it. And then Steeger turned up again; that was when he shot Constable Slugger, and they couldn’t catch him for either case. Funny, too; because the police knew perfectly well that he had done both murders, and Linley came along and told them how. Still, they couldn’t catch him. Well, they could catch him whenever they wanted to, but what I mean is there’d have been a verdict of Not Guilty, and the police were more afraid of that than a criminal is afraid of the other verdict. So Steeger was still at large. And then there came a case of a man that did three murders, and Linley helped the police over that. They got that man. And then the war came, and murder looked a very small thing, and no more had been heard of Steeger for a long time. Mr Linley got a commission, and, when they found out about his brains, he went to the War Office, to what they call M.I., and I went to be, what I never thought I’d be, a private soldier, and Numnumo was heard of no more, except for a few little wails from the advertisers, saying what a good thing it used to be. Yes, I got called up in the summer of 1940, and was put in barracks near London. I used often to lay awake at night under my brown blankets, thinking of the battles the British army had been in, things I’d heard of at school, and more that the sergeants taught us about, and trying to picture what they were like and what they sounded like; and all the while a battle raging over the barracks. I got the idea that some of those old battles might have been fairly quiet compared to those nights. But I don’t know.

Well, that battle was over in a year. We won it; I mean our airmen did. But we hadn’t much to spare. It was a nasty time. I don’t think the Germans would behave quite like that now. They’ve spoken very nicely of late about not destroying culture and civilization; but they didn’t quite understand in those days, and used to talk about rubbing our cities out; and they very nearly did. But I’m not going to write about the war; perhaps somebody will do that in a hundred years, beginning at 1914 and forgetting about the years from 1919 to 1939, and going on till it stops, and a very interesting tale he should make of it. I’m going to write about Mr Linley again. That brings me to the year 1943. I had a day’s leave, and got a lift on a lorry, and slipped up to London, and the first thing I did was to go round to Lancaster Street to have a look at the old flats. I wanted to have a look at them just to prove to myself that it was true that I hadn’t always lived in a barrack-room. Well, they’d gone, those flats had. There was a square of grass and weeds and flowers; and there was a lot of groundsel. And in a way I liked the look of it, though it wasn’t what I had come to see. They were rather dingy and dark, those flats as I remember them, and they called them Clarence Gardens. Now they really were gardens; or at any rate there was sunlight there, and some sort of flowers. I suppose there’s no one that doesn’t sigh for the country a bit some time or another in London, and here a bit of the country was, wild as any bit of the country you could see, even wilder than some of it. And for a moment I was glad to see this bit of sunlight and grass among all those miles of pavement, till I thought of all the slaughter that had gone to growing that groundsel. I looked up into the air then to see if I could locate just where our flat had been, because it seemed odd to think that I should have once been walking about, or sitting and listening to Mr Linley somewhere up towards the blue sky. And as I turned my eyes up from the groundsel I saw an officer standing near me and looking at me. I came to attention and saluted, and the officer said, ‘Why, it’s Smethers.’

And I said, ‘It’s not Mr Linley!’ For he looked so different in uniform.

And he said: ‘Yes, it is.’ And he shook hands.

And in a moment we were talking about the old flat.

Then he surprised me very much by saying: ‘You are just the man we want.’

Well, I’d had all sorts of jobs to do since they made me a soldier, all sorts of jobs, but nobody had ever said that to me. And here was Mr Linley saying it, just as if it was true.

‘Whatever for?’ I asked.

‘I’ll tell you,’ he said. ‘That man Steeger is getting to work again.’

‘Steeger!’ I said. ‘The man that bought the two bottles of Numnumo.’

‘That’s the man,’ said Linley.

‘And shot Constable Slugger,’ I said. ‘What’s he up to now? His old tricks?’

‘Worse,’ said Linley.

‘Worse!’ I said. ‘Why, the man’s a murderer.’

‘He only murdered a couple of people, so far as we know,’ said Linley. ‘He was only a retail murderer. But he’s a spy now.’

‘I see,’ I said. ‘He’s got into the wholesale business.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘and we want you to help watch him.’

‘I’d be glad to help,’ I said, ‘in any way I could. Where is he?’

‘Oh, he’s here all right,’ said Linley. ‘He’s in London.’

‘Why don’t you arrest him?’ I asked.

‘That’s the last thing we want to do just yet,’ said Linley. ‘It might warn a lot of others.’

‘What’s he done this time?’ I asked.

‘Well,’ said Linley, ‘they found out only the other day that he has recently received a thousand pounds. Somerset House found it out, and reported it.’

‘Has he been killing a girl again, and getting her money?’ I asked.

‘No, that’s not so easily done,’ said Linley. ‘He found poor Nancy Elth with her two hundred pounds, but he can’t find a girl with money every day.’

‘Then where did the thousand pounds come from?’ I asked.

‘The easiest money of all,’ said Linley.

‘Spying?’ I said.

‘That’s it,’ he said. ‘It’s the best paid of all the crooked jobs in the world. Especially at first: they’ll give almost anything to get a new man into their clutches, provided he’s likely to be of any use to them. And Steeger should be a lot of use. He’s a really skilful murderer, and should be a skilful spy.’

‘And where is he?’ I asked again.

‘We’ve found him all right,’ said Linley. ‘There never was any difficulty in finding Steeger. The difficulty always was in proving he’d done it. Aye there’s the rub, as Hamlet remarked.’

‘And what has he given away?’ I asked.

‘Nothing as yet,’ said Linley. ‘That’s why we want you to help watch him. A thousand pounds is good pay, and it must be for good information. And of course it has been paid by a German in this country, or a Quisling or some such cattle. But they’ve not been able to get it out of the country yet.’

‘How do you know?’ I asked.

‘Because there is only one thing that the Germans would pay on that scale for,’ said Linley, ‘and we know that they don’t know it yet.’

‘What’s the thing, might I ask?’ I said.

‘Where the second front is going to be,’ said Linley. ‘We think he has found it out somehow and the other spy has paid him for it out of his loose cash. But it’s worth a million if he can get it to Germany. And a hundred million would be pricing it low, but they’d probably pay him fifty thousand for it. Anyway we know they don’t know it, and the thousand pounds is a mere tip. But that’s what the tip would be for.’

‘How did he find it out?’ I asked.

‘We don’t know as much as all that,’ said Linley.

‘I see,’ I said. ‘And you want him watched so that he doesn’t get out of the country.’

‘Oh, he can’t do that,’ said Linley. ‘But we want to see that he doesn’t send the news.’

‘How will he try to do it?’ I asked.

‘By wireless, probably,’ he said.

‘How will he do that?’ I asked.

‘Well, we’ve located all the sending-sets,’ said Linley, ‘that have ever spoken since the war began; but there may still be some silent ones hidden, and waiting for a bit of very big news like this. And I think we’ve located all the carrier pigeons; though there might be one or two of them somewhere that we don’t know of; but it’s easier to hide a wireless set than a pigeon, because you don’t have to feed it.’

‘And you want me to watch him?’ I asked.

‘Only now and then,’ said Linley. ‘He’s in London, and we know more about all the houses here than you’d think. We aren’t really afraid of his working a sending-set anywhere in London, but we can’t answer for the open country, and he has to be watched when he moves.’

‘What about the other man,’ I asked, ‘the spy who pays him?’

‘He lies very low,’ said Linley, ‘and we haven’t spotted him. But that’s only because he lies so low, and if he went about and did odd jobs with a wireless sending-set, we should have spotted him long ago. For that reason we don’t think he’ll try to do this job, but will leave it to Steeger. After all, Steeger’s a pretty smart man, and it isn’t everybody that has committed two murders and is able to walk about at large in England, Scotland or Northern Ireland.’

‘I’d be glad to watch him,’ I said, ‘if you think I can do it.’

But I said it rather hesitatingly, because, though it was very nice of Mr Linley to offer me such a job, I had begun to see by then that it was a pretty important one, and, to tell you the truth, I am not quite the kind of man to be given a big job like that. Maybe I might have been if I’d been brought up to it, and given the chance of handling big jobs early, but I spent all my time pushing Numnumo, and was never given anything bigger, and somehow or other I seemed to grow down to the size of my job; or perhaps the job was only the size of me, and that’s why I was given it, and never given anything bigger. And now here was Mr Linley offering me a job that mightn’t look very big if I did it well, but, if I did it badly and let that man get out his news of where the second front was to be, why, it might cost the lives of thousands and thousands of men. That’s why I said ‘if you think I can do it’, and by the way I said it I sort of showed him I couldn’t: I thought it was only fair. But Linley said: ‘That’s all right, you’re just the man for it.’

‘Very glad to do my best,’ I said. ‘Do I go in uniform?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘That’s just the point of it. We don’t want to give the idea that the British army is watching him. Or that anybody is. But somehow or other, though you look the perfect soldier in that kit, in plain clothes you might not give quite the impression we want to avoid.’

Of course I didn’t look the perfect soldier at all, even in uniform, nor I never will. It was nice of him to say it, but I saw his point.

‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘I’ll just go back a few years to the Numnumo days and I’ll hang about somewhere near him and I shan’t look very military.’

‘Well,’ said Linley, ‘I’ll let you know. We shan’t want you just yet. We have him watched all right. But, if he got anywhere near a wireless, we’d want someone extra to watch him. He’d have to be watched very close then. Five seconds might do it, and he might pretty well ruin Europe. That’s to say, any of it that’s not ruined already.’

All this, I may say, was at the end of June, in 1943, when all the plans for the invasion of Europe were ready, and the Germans were still guessing. And, while they guessed, they had to strengthen a line of two or three thousand miles. One word from Steeger, if he had got at the truth, would bring it down to a hundred miles, and save them a lot of trouble. That’s how things were when I parted from Linley that day just after midsummer, and a very nice lunch he gave me before we parted, at a big hotel, in his smart uniform and all, and me no more than a private. We didn’t talk any more about Steeger there, even when there was no one in hearing. He wouldn’t say a word about that sort of thing indoors. Well, I thanked him for all he had done for me, and for remembering me like that, and giving me such a fine lunch; and away I went on a bus back to my barracks. And only a week later I got a letter from Linley. It just said, ‘That job is all fixed up, and your C.O. has been written to.’ And I was sent for to the Orderly Room next morning and given a travelling warrant, and told to report at the War Office on the same day, for special duty, which would be told me when I got there. So off with me up to London and to the department of the War Office that I was ordered to go to, and there I was fitted with a suit of civilian clothes and given a ticket for a concert at the Albert Hall. What I had to do was to go to the seat whose number was on the ticket and sit there and take as much interest as I could in the music, and at the same time watch the man who would sit on my right. That’s all they told me while they were fitting me with my suit of clothes. And then Linley came in while they were brushing my hair, because they said it had too military a look; and Linley made everything clear to me. The concert he said was to be broadcast, and Steeger had chosen a seat right under the microphone, and that had been reported. They were still sure that he had got hold of the secret of the second front, and it was pretty certain that he would say something about it during the interval, and the whole world would hear him. Of course he had to be watched the whole time, but he would probably do it in the interval.

‘And how am I to stop him, sir?’ I asked.

‘Well, I’ll be there,’ said Linley, ‘on the other side of him, and I think I’ll be able to stop him, but I’ll be glad of your help, especially if he starts to shout out the name of the country that is going to be attacked. You must shout him down then, or stop him any other way. But we don’t think he’ll do that; in fact it’s a thousand to one against, because he’d give away that the enemy had been warned, and also he’d be hanged, which he has taken a good deal of trouble to avoid so far. What he is almost certain to do is to signal, and I’ll be watching for that, but I might be glad of your help.’