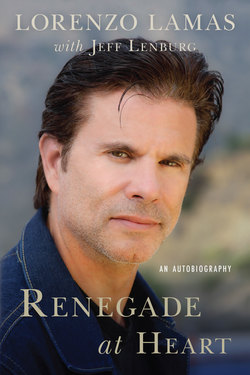

Читать книгу Renegade at Heart - Lorenzo Lamas - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE Caught Between Two Worlds

ОглавлениеPEOPLE ASSUME just because you are the son or daughter of a celebrity, you spend your whole life around other rich and famous people, living in the upper echelon of society. You have it easy. In my case, nothing could be further from the truth. As I would come to learn, fame and fortune never solve. My parents are examples of that.

Both are highly talented professionals so busy working and so preoccupied with their careers that they never achieve true, lasting happiness together. Surely they have the right intentions when they marry, buy a home together, plan a family, and, of course, have me. To the world, they are Hollywood’s happiest couple. Yet, as I discover at a very tender age, just because you make plans doesn’t mean they will always work out as you hope.

My father, known to the world as Fernando Lamas, is a rakishly handsome, flamboyant, and athletic man who loves life and beautiful women—not necessarily in that order. Born on January 9, 1915, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he grows up in a country imperiled by political and economic unrest and yet rises above it all. At a young age, after developing a love for theater, he studies drama at school. Later, he abandons his studies for athletic pursuits—horse riding, fencing, boxing (winning the middleweight amateur title), and swimming (becoming the South American freestyle champion in the 1937 Pan-American Games). While still in his teens, he returns to his first love—acting, appearing onstage, then on radio, before making his first motion picture at the age of twenty-four. By 1942, he establishes himself as an Argentine cinema celebrity, proudly starring in over a dozen pictures, producing six and directing two, and living up to his on-screen reputation as a ladies’ man.

With a natural eye for beauty, Dad holds true to a basic philosophy when it comes to women, based on his old-world values: “Women are the same all over the world, and I say God bless them,” he good-naturedly explains to a reporter—although with some differences, he points out: “American women are slightly different from Latins because they have more freedom. I take my hat off to them; the women here have earned their position of equality with men. They can influence men by direct means, whereas Latin women cannot. The Latin women have to remain in the home, and the man is the master. Whatever influence they have must come by indirect means.”

Brought up to believe that a woman’s place is in the home, Father is attracted to women with like values. In 1940, he falls in love with and marries fellow Argentine actress Perla Mux, who costars with him in fourteen films from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. The union lasts four years, producing a daughter, Christina, before ending in divorce. Then, in 1946, he marries a second time to Lydia Barachi. Six years later, in September 1952, they split after having a second daughter, Alexandra (“Alex”).

In 1950, Dad flees to Hollywood to appear in a supporting role in his first American feature for Republic Pictures, The Avengers, before signing a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to star as a romantic lead in English-speaking movies. After his MGM film debut in Rich, Young and Pretty with Jane Powell in 1951, he quickly becomes one of the most promising Latin actors since Rudolph Valentino and Ramón Novarro, as he climbs his way to international stardom. My father’s story—a foreigner with a foreign name and accent making something of himself in an alien land—becomes a great example to me. It teaches me an important lesson: If you work hard and pay your dues, almost anything is possible.

Despite his success, my father is realistic about how fleeting fame is—a lesson he later imparts to me when I become an actor. “Hollywood is a momentary place,” he says, “and I feel this is my moment. I like it here, and I’d like to stay. But perhaps two years from now, some fellow in the balcony of a theater in Kansas City will get up and say, ‘Aw, I’m getting tired of seeing that guy on the screen.’ Six other people might join him and that would be the beginning of the end.”

Long before I am a twinkle in my father’s eye, Dad’s romances with many of his female costars become well-publicized affairs. His torrid relationship with tempestuous platinum-blond legend Lana Turner—sparked during their making of MGM’s The Merry Widow (1952)—makes national headlines as the thrice-married actress seeks to make my father husband number four. The press turns their affair into a carnival; the two lovers are unable to even go out of town in order to retain some semblance of privacy. Finally, in October 1952, they call off plans to marry, although three months later Lana goes ahead and divorces her then-husband, wealthy sportsman Bob Topping, when rumors resurface that my father and she still might wed.

While on loan to Paramount in 1953 to star in Sangaree, a 3-D Technicolor drama for Pine-Thomas Studios, Dad meets his match. He falls in love with his luscious, flaming redheaded costar: my mom, Arlene Dahl. He is immediately attracted to her “softness,” the thing he looks for most in a woman. Mom possesses that quality and more, and the fact that her father has raised her with that same old-world philosophy about women makes them a perfect match.

Mom is a Minneapolis native of Norwegian descent who worked various jobs through high school and was active in local theater groups before embarking on a show-business career. After starring on Broadway and in two features for Warner Bros., she finds her greatest success at MGM, just like my father. She costars as the female love interest in many successful feature films for the studio, including The Bride Goes Wild (1948) with Van Johnson and Three Little Words (1950) with Fred Astaire.

Mom becomes Dad’s steady the same year MGM loans them out to costar in their second Pine-Thomas Studios film together, the independent romantic adventure for Melson Pictures Corp., The Diamond Queen. At the same time, my father is seeking his release from his MGM contract after more than four years in the studio’s service. Dad and Arlene are the talk of the town and are treated like Hollywood royalty everywhere they go. Their union does create quite a stir with the media because Mom is not yet divorced from her first husband, actor Lex Barker (who, after divorcing Mom, dates Lana Turner, the woman Dad almost married), and because Father is eleven years her senior.

Their relationship is contentious and rocky during their two-year courtship and even after I am born, as evident in this exchange with a reporter during a November 1953 interview:

“How about some pictures kissing her?” the photographer says to the reporter.

In no mood to act lovey-dovey, Mom, exhausted from her stage performance the night before with José Ferrer in Cyrano de Bergerac, turns away from Dad, who smooches her on the cheek and announces, “The patient will live!”

After considerable coaxing, Mom eventually complies after the reporter asks her, “What plans have you after this show?”

“I guess to get a good rest.”

“Might as well quit fooling around,” the reporter adds. “Do you two have any plans to get married?”

“You’ll be the first one to know it,” Dad says with an unctuous grin.

“Aw, tell her first,” the reporter jokes.

The reporter excuses himself and pulls Dad outside. He asks him the same marriage plans question privately.

Dad says, “We may. We’re thinking it over carefully.”

“Are you free to marry?” the reporter asks.

“Of course. Since October!”

The reporter cracks a smile. “Sorry, but I can’t keep up with you guys.”

“Wait a minute!” Dad says seriously. “One marriage and one divorce ain’t bad! We’ll let you know.”

On June 25, 1954, after deciding they cannot live without each other, they quickly marry in a simple ceremony at the Last Frontier Hotel’s Little Church of the West. Former tennis champion Gene Mako and his wife, Laura (“Larry”), serve as best man and matron of honor.

My parents move into a palatial spread in Bel Air, the same place I briefly call home after coming into this world on January 20, 1958. When Mom goes into labor, Dad is doing what any good actor does: He is working to provide for his family. He is in the middle of rehearsing for NBC’s Jane Wyman Theater (yes, the same Jane Wyman I would costar with years later on Falcon Crest), which is broadcasting live that night, when the hospital calls to tell him, “Mr. Lamas, your wife is about to give birth.”

Like most fathers, Dad always wanted a son. After receiving the news, he sprints from the set despite Jane protesting, “It’s almost show time and we have no second act.”

Turning to her as he runs past her, my father famously hollers, “My son is about to be born. I’m not missing it for anything.”

On April 10, 1958, my parents baptize me at the Church of Religious Science in Hollywood. Laura Mako is my godmother; architect William Pereira is my godfather. Dr. Ernest Holmes, the church’s founder, also attends; Dr. William Hornaday conducts the baptismal ceremony.

My early years are not always easy and happy. I never enjoy the standard Hollywood childhood most second-generation kids of celebrity parents do. In mid-February 1959, a month after my first birthday, Father is suddenly out of the picture when Mom sues him for divorce, claiming she has “lost all contact” with him. After a brief separation, they try to make the marriage work again. On the surface, it appears it is.

But even though my parents share a zest for life, they are polar opposites. Mom is a reserved yet fastidious overachiever; Dad is a gregarious and proud macho man. Mom dresses me impeccably in ruffled shirts and velvet pants; Father talks to and treats me like a little adult.

I come to revere and idolize my father as he whisks me off with him in his sporty Alfa Romeo convertible with the top down, taking me almost everywhere, including to meetings he has in Hollywood. He props me up on a chair, and I listen quietly to him and all these grown-ups talk about the business in my presence as if I am one of the guys. In reality, I am just a two-year-old, wet-behind-the-ears, snot-nosed kid who still pisses in his pants and has no idea what in the hell they are talking about.

Occasionally I also accompany Dad to the sets and locations for productions he is filming. Going to the studio is so surreal and magical. It is like watching a group of adults play dress-up like it’s a real-life Mickey Rooney–Judy Garland Andy Hardy movie unfolding before my eyes. The sets are built and the cast members are in their costumes and makeup, ready to put on the “big show” and help save Farmer Tom from losing his farm.

Even then, I never quite understand what my father does for a living. He rarely talks about acting or moviemaking to me when driving us to the studios. Instead, he is like some kind of wise man on the mountaintop. He readily dispenses his wisdom to me on just about anything and everything, even though I am far too young to understand most of what he is saying. With the bravado that made him famous as an actor, he starts the same way every time: “Lorenzo, you’ll be happy someday; I’m telling you this,” and thrusts his forefinger into the air as if he is acting in a serious melodrama. I become a fast learner in the art of nodding.

I never knew then as I would later that Dad is the kind of person who always puts a positive spin on things. It is his nature. In June 1960, an Associated Press reporter sits down to interview my father and asks him to comment on his marriage to my mom. He famously proclaims that although it has had its share of rough sailing, their marriage is “succeeding” because “too many people in Hollywood forget that they are men and women first, and actors second. They bring their roles home from the studio and try to live them at home. A man is a man and a woman is a woman. No matter if he wins an Academy Award, it means nothing if he does not have understanding at home.”

Father adds, “Women especially are emotional. That is their nature. An actress deals in emotions in her work. If she continues playing the part at home, the result is chaos. Man was meant to be dominant. When an actress’s career zooms higher than her actor husband’s, it is an impossible situation. Soon she starts paying the bills. He cannot stand by and retain his self-respect.”

Because they are in step with the societal norms of the time, including male superiority in the household, Father and Mom have a very traditional marriage. As head of the household, he sets ground rules from the first day. He pays all the bills and lets Mom do whatever she wants with her earnings. Even as a married man, however, he remains the free-spirited individual he has always been, doing whatever he wants when he wants. So twice a week, he goes to the fights—boxing is one of his true loves. Sometimes he tells Mom; other times not. I am sure most men reading this love the fact my father lived such a footloose and fancy-free existence. But even back in that day, not every woman was as patient and subservient as my mother. In fact, she wasn’t either.

The AP interview runs nationally, and once again, to the world, my parents appear happy in their marriage. As that two-year-old, wet-behind-the-ears, snot-nosed kid who still pisses in his pants, I never suspect anything to the contrary. Of course, my parents are actors.

Five months later, Mom suddenly flies off to Mexico to get a quickie divorce. On October 10, 1960, she files. Five days later, she marries wealthy Texas oilman Christian R. Holmes III, after he has finalized property settlement details of his divorce with his ex-wife. Mom and Christian are wed at a private estate in Cuernavaca in front of invited guests that include his business associates and socialites from nearby Mexico City. It is the third marriage each for Mom and Christian, a Marine captain during the Korean War who has oil interests in Texas, Louisiana, and South America. The following February, Mother’s desire to have a church wedding prompts her and Christian to exchange vows again in the Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd in Reno, Nevada.

Just like that, a new man suddenly moves in to live with us, while the man I have come to love and admire as my father, the one who whisks me off in his fancy convertible to Hollywood meetings, vanishes. My world shatters into a million pieces. I feel a huge loss, a huge void. The whole thing is like a bad movie I cannot get out of my mind. I cry myself to sleep many nights. It is all so confusing. The father I have grown to love in such a very short time is no more. My life, as I know it, is not the same. Nor will it ever be. My parents’ divorce traumatizes me in ways that will not become evident until much later.

I do not ever remember Mom really talking to me about Dad, the divorce, or her marriage to Christian. Perhaps she thought I was too young or would not understand. Whatever the reason, it is as though that part of her life and my life with Dad is simply swept under the rug and forgotten. With her new man and new husband in her life, Mom carries on. I am expected to do the same. It takes a long time for me to warm up to Christian. He is not my father, despite his best efforts to fill his shoes, and I long for the day when I can see Dad again and be in his company.

In August of 1961, Mom and Christian welcome a baby daughter into the world: Carole Christine. Mom and Christian arrive in style, in a limo from the hospital, carrying her in a beautiful bassinet.

That same year Father reunites with his former flame and MGM screen star Esther Williams. The two of them pack their bags and move to Italy, where they work and live together for almost three years. Devoting her life to my father, Esther leaves her children in the care of her alcoholic ex-husband, Ben Gage, a decision she later pays dearly for. Naturally, the news Dad is moving far, far away devastates me. It is yet another reminder of the loss in my life: that Dad is not only not part of my life anymore, but he is now in a place halfway around the world where I will never see him. My separation from him and longing for his return dominate my existence. I miss him so much.

Meanwhile, Mom does everything to make her third marriage work while providing me with a safe and stable environment in which to grow up. My childhood home for the next eight years is a stunning one-story, rambling five-bedroom California ranch-style house with a shake roof and white stucco siding in Pacific Palisades, nestled between the Santa Monica Mountains and Santa Monica Bay, with a backyard overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

After divorcing my father, Mom bought the house in 1960 for $64,000. The home was originally built in the late 1950s by a local developer as part of two neighborhoods, or tracts, he developed near Will Rogers State Park: Villa Grove and Villa Woods. We are the last house at the end of the cul-de-sac in Villa Grove. As the only housing developments in Pacific Palisades at the time, we are completely isolated and protected from the rest of the world. It is a magnificent place to live. There is no crime, and my friends and I play ball until nine o’clock at night during the summer because it is so safe.

Because my first name is hard for them to pronounce, my playmates settle on calling me “Lucky.” The nickname sticks. After I become an actor, a fan has a T-shirt made for me with “Lucky Lamas” emblazoned across the front. As my life plays out, I start to believe “Lucky” is my real name.

With so many oil interests to manage, my stepfather Christian is frequently on the road on business. Mom is always super-busy working, too. She is either headlining a stage show in Vegas or going to New York to talk about her cosmetics business. She is hardly home herself. And even when she is, she is always too busy doing something. Most days I feel lost and lonely. I become a deeply troubled fat little boy who eats a lot out of frustration. I long for what my friends have and what every kid wants: normalcy. My friends all have normal lives with normal parents not in show business. They function and do everything like normal families. I do not have that. I have a mother who leads a fashionable jet-set life. Then, when she is home, she invites society and famous people over for dinner and requires me to dress up and sit there smiling like a dummy. Not only that, I have a father who lives far away, a father I never see and hardly know.

After school, I spend my time at friends’ houses just so I can have a normal family dinner rather than help Mom entertain her adult friends, people I do not even know. I’m frequently wishing for what I do not have: wishing my parents were David’s parents, or Jeff’s parents, or Sally’s parents. Dealing with such tumult and confusion is hard, especially for a kid my age.

When Mom flits out of town, she usually leaves my sister, Carole, and me in the care of our nanny, Emily Gibbs. Housekeepers come and go, but Emmy, as I called her, becomes the one constant in my life. She fills the void. She nurtures me. She consoles me. She disciplines me—almost always for good reason. She fills the hole in my aching heart. I count on her for everything. Emmy is there for me, from about age two until I turn eight (when Mom moves us to New York for the first time).

Emmy is this sweet, soulful, God-fearing woman with a heart of gold, a devout Christian who teaches me more about karma than any New Age book ever can. One thing I learn from Emmy is to never, ever lie. She has me grab a switch from a hickory tree out back if I do (and if it is not a big enough switch, go get one bigger). Then she swats my ass so hard that I never think of lying again.

Besides many other wonderful lessons, Emmy teaches me how to pray. Every night before tucking me tightly into bed, she kneels and prays with me at my bedside. With my hands clasped and pointed toward the heavens, I silently pray for the same thing. One night, I turn to Emmy after praying and ask with all the innocence of a six-year-old, “Emmy, why are you black? Are black people bad?”

“Child,” Emmy says, wagging her finger forcefully at me, “I never want to hear you say that again for the rest of your life.”

“I’m sorry, Emmy,” I answer quietly.

Emmy quickly softens and lowers her voice as she explains, “Honey, God gave us all different colors. God made us the colors of the rainbow. Each of us is judged not by our color but what we do in this world.”

Heavy words for a six-year-old, words I have never forgotten. As I was growing up around Santa Monica in the 1960s, the only black people I saw worked as nannies, gardeners, and other service providers. That innocent question of a six-year-old and the honest answer from a woman who lived in the faith of God really set the tone for my acceptance of everyone. I learned how to be a Christian because of one Emily Gibbs.

From the time I turn three, I suffer from chronic bronchitis, a condition doctors think is either psychosomatic (from the separation anxiety of missing my father) or smog-related. Whatever the cause, I have serious trouble breathing at night. Like any good mom, Emmy is right there. The minute I start coughing in bed, she rushes into my room and sits next to me.

“You poor child,” she says softly. “Emmy will get you better.”

She then rubs Vicks VapoRub on my chest, puts a hot terry-cloth towel over it, sits, and waits patiently until I fall asleep.

Waking around seven o’clock every day, I usually run straight to Emmy’s room because I know she makes me a big breakfast every morning. Nobody makes better breakfasts than Emmy. On the morning of Monday, November 25, 1963, I find her door mysteriously locked. I knock softly. Emmy greets me with tears streaming down her eyes and moon-shaped face.

“Emmy,” I immediately ask, “why are you crying?”

“Oh, honey,” she says, dabbing her eyes with a handkerchief, “it’s a terrible day.”

“What? Why?”

Sobbing, Emmy sinks into her armchair in her bedroom. On the black-and-white television in her room, a television news anchor is describing the action as a horse-drawn flag-draped casket proceeds reverently down the streets of Washington, D.C. It is the memorial service honoring President John F. Kennedy, assassinated three days earlier.

“A great man was shot,” Emmy says, misty-eyed, “and he’s going to be laid to rest today.”

I climb into Emmy’s lap. We sit there mesmerized for hours watching the funeral procession on television, just the two of us. Throughout the sad day, she reflects on what a great man and humanitarian the president was. It was a day the two of us, Emmy and I, grew even closer.

Despite Emmy being there to tend to my daily needs, what I lack is my mom’s love and attention. Her absence truly saddens me anytime she whisks out of town on business and I begin to feel angry and resentful about her constant absences. Much later, as a mature adult who works his entire career to put bread on the table and is absent, sometimes for long periods, to earn a living, I come to realize Mom was just doing the same. However, back then as a six-year-old child, I fail to fully understand the sacrifices she is making and why. One day, just after Mom returns from a trip and the suitcase rack in her bedroom cradles her still-unpacked suitcase and she still holds her purse in her hand, I walk into her room and announce, “I want a ball and want you to take me to the store.”

“Honey, I can’t. Mommy is really busy,” Mom says, turning her back on me. “Mommy is always busy.”

It is not what I want to hear. Dressed in black boots with red tips, I get so mad I haul off and kick her right in the shin. Mom stands there wailing in pain. Emmy, who sees the whole thing, comes running into her bedroom.

“Lorenzo Fernando Lamas,” Emmy bellows, “what did I see you do?”

I think, “Uh-oh, Emmy caught me. The wrath of God is going to land on me.” Breaking into tears, I immediately beg for forgiveness. “I’m sorry, Mommy, I’m sorry.”

Mom, still crying in pain, manages between sobs to ask, “Lorenzo, why did you kick me?”

I look at her. “I don’t know. I just got angry.”

Emmy grabs me, takes me out of the room, and says sternly, “Lorenzo, you go outside and find the biggest switch you can and bring it back to me. Right now!”

Now I am really sobbing. “All right, Emmy.” Sniff, sniff. “I’ll go.”

I walk out crying crocodile-sized tears, go straight to the hickory tree, peel off about a three- or four-foot-long switch, and bring it back in to Emmy. She swats my ass with four or five of the hardest lashings I have ever received, and I cry my heart out with each whipping. I can assure you, I never did anything like that to my mom—or anyone else—again.

Despite the geographical distance between us, my father is never far from my mind. I often wonder if I will ever see him again and if he ever thinks of me. In 1962, I get a big surprise: He flies me to Italy to see him. It marks the first time we see each other since my parents’ divorce and his leaving the country with Esther.

Because I am underage, Lola Leighter, a close friend of my father’s and someone who is like a grandmother to me, accompanies me on the TWA flight to visit him. I cannot express how much that trip and seeing him means to me. We pick up right where we left off: He drives me around in his Alfa Romeo convertible to the ancient city of Rome and the harbor and beaches of nearby Ostia and spends every minute of every day with me. I am this chubby-faced, scrawny kid but he makes me feel very special. Despite everything, he is still my hero. I know the love is there. I know for certain he loves me and I love him.

Father captures every moment with his Brownie camera. He shoots countless black-and-white photos of me that he then turns into little handmade storybooks, complete with handwritten captions with each photo describing in a charming, funny way where we are and what we’re doing. Although their pages have yellowed and frayed over the years, those simple storybooks have not dimmed with age. They tell about the special bond between a father and son.

One of my favorites is one he titles The International Sheriff, featuring photos from our day trip to Rome, including outside of St. Peter’s Cathedral. In it, I star as the macho, gun-slinging sheriff (as “a stand-in for Mr. Lamas . . . his father”) who comes face-to-face with a vicious Indian (played by yours truly in a dual role).

“Where is he?” I ask in one caption, with a scowl on my face. “I got to find him.”

“Looking for me, Sheriff?” It is him—I mean, me, the Indian.

“Draw, you dirty Indian! I got you. I’m tough . . . I’m Lorenzo Lamas!”

It’s as if my father was already laying the seeds for my acting career without me even knowing it. Little do I realize that the renegade in me is starting to surface. I starting to come out of my shell—thanks to a little nudge from my father.

In the storybook titled La Dolce Vita, I play this swinging bachelor much too busy reading my Pinocchio comic book to talk. Finally, I instruct my chauffeur, “To my cabin on the beach, Perkins, and don’t bother me, I’m reading!” In no time, I am spending the day at Ostia Beach (in a small storybook, it is amazing how fast time flies!), walking the sand and swimming nude as if I am some kind of ladies’ man: “This is the life! No clothes, my beach house, my boat and a few girls. Hah!”—my father’s words!

Father goes to great lengths to show his love for me on that trip, as evidenced in The Two Guys, the third and final storybook he does for me. Inside are panels of old two-by-three-inch photographs of us lovingly cobbled together—“two happy guys”—on Ostia Beach and “two not-so-happy guys” in front of his classic Alfa Romeo convertible at Fiumicino Airport moments before my flight back to the States. The final captions on the last page in Dad’s handwriting say it all about the bond between us, as well as his deepest regrets over our separation:

“I’ll see you soon, Daddy!”

“Be a good boy, eh?”

“NO ENDING!”

Our actual final minutes together are bittersweet. Tears well up in my eyes when I say goodbye to Dad as Lola and I board the plane. It is so hard, not knowing when I will ever see him again, that my heart aches just thinking about it.

“Daddy, Daddy,” I say, running into his arms, sniffling, “please come with us, Daddy.”

“Someday, Lorenzo, someday,” he says. We lovingly embrace. “Promise.”

One last embrace, then Lola pulls me away with “Lorenzo, we need to board.”

For a moment, I see real emotion in my dad’s eyes. He feels the same pain, the same turmoil, the same tug-of-war with his feelings I do, even though he does not outwardly show it like I do.

“Goodbye, Son!”

At that, Lola and I walk off. Lola tugs me along as I keep glancing over my shoulder. Father is still standing where we left him. He is watching my every step. I pause a second and wave. Dad smiles broadly and returns the favor as Lola and I make our way to the plane. Then I suddenly lose sight of him and he disappears into the mass of humanity moving about.

Every day I hold on to that promise that I will see my father again. In 1963, it comes true when Dad and Esther move back to Los Angeles. The news makes me the happiest boy on the face of the planet. It means my father and I can see each other any time we want. Earlier, when I said I prayed the same prayer every night, it was that my father and I would be together again. Finally, we are.

Dad and Esther rent a guesthouse on Lola’s sprawling estate off Sunset Boulevard in Brentwood until they buy their own house in Bel Air four years later. That February, for my fifth birthday, Dad and Esther throw a lavish birthday costume party at Lola’s in my honor. They dress me up as a pint-sized caballero. Actor Chad Everett (later of TV’s Medical Center fame) is among the invited guests. He brings a pony for all us kids to ride. Dad even gives me my earliest tips on picking up women when he introduces me to a little señorita who catches my fancy. Of course, by now, I am a master at nodding and letting him do all the talking.

It is the most time my father and I ever spend together. From kindergarten through third grade, he picks me up every day from school and drops me off at Lola’s main house while he hangs out with Esther at the guesthouse. For me, Dad becomes the image of what it is to be a man, and quite an image it is: this huge voice and grand presence always willing to share and teach me many important lessons on becoming a man. One of my favorites is his teaching me how to give a person a firm handshake.

“Look them right in the eye, Son,” he says and then practices with me. I am only six years old. “Now shake my hand.”

I extend my right hand, grip his loosely, and shake.

“That’s not firm enough,” Dad admonishes me. “Don’t give me a fish. Give me a handshake.”

I try again.

“In the eye, look me straight in the eye,” he reminds me.

I stare so hard into his eyes, mine tear up from the strain.

“Good. Now again.”

Anytime I come over to visit or stay for dinner, Esther is always accommodating. She is an honest-to-goodness home-loving wife and mother through and through. She is also a terrific cook, as I quickly discover, and is truly in her element whenever she entertains. Even when we all go together to the beach with my friends, she really puts out a feast. She cooks the kind of meals served for dinner on Saturday night—mouthwatering, home-cooked lamb shanks or pot roasts as the main course, with roasted corn, potatoes, and asparagus—all made in a hibachi right on the beach. Dad makes it my job to load Esther’s Mustang convertible before we pick up my friends Bill and Dave, or Jay and Jeff, all of whom live up the street (they are so skinny Dad collectively nicknames them “The Bird”), and head to the beach.

My father makes a circle in the sand with the heel of his foot around him and Esther and the food every time we go to the beach. It means that area is off-limits. Dad says, “You boys stay out until you are called.”

Of course, my father has an ulterior motive: The last thing he wants is a bunch of crazy kids kicking up sand on his lamb shanks!

As Esther cooks and Dad sits and reads the newspaper, we do what most kids do when they go to the beach: frolic and have fun. We have a blast together—body-surfing, digging holes in the sand, chasing each other, tackling each other. The water is so cold we come out freezing and shivering, and bury ourselves in the sand from head to toe to keep warm.

One of Dad and Esther’s favorite pastimes is gardening. They love it as a stress reliever and enlist me, whether I want to or not, to assist them. It is again all a part of my father’s effort to instill responsibility in me at an early age. He is of that old-fashioned mind-set that if I am old enough to hold a trash bag, I am old enough to stand there and hold it for him.

“Over here, amigo,” Dad says before instructing me exactly on how to hold the bag as he stuffs in ivy clippings, overgrown brush, or whatever else he is cutting back for the fire season.

After we finish, my quirky father throws all this stuff—large bags of clippings and bundles of branches twined together—in the back of Esther’s stylish Mustang convertible as if it is a dump truck and takes it all to the nearby dump. Incidentally, million-dollar homes in the very affluent neighborhood known as Summit Ridge now sit on that dump site. Today, every time somebody successful tells me they live in Summit Ridge, I laugh because those homes are built on top of crap and God knows what else.

Any spillage from the bag is also my responsibility. Dad points to some clippings that never quite make it inside. “Be a good amigo and pick those up, too,” he says, “and when you are done, help Esther.”

Esther never really needs my help. She seems to have things under control. My father, however, believes it is the responsibility of a man to do what women cannot do for themselves. The first time I walk over to help Esther, she smiles down at me. I never say a word to her and do exactly as told. After bagging the last of the garden clippings and mess, she pats me on the shoulder and says, “It’s okay if you help, but your father is the one who really needs your help.”

We look over. Dad is struggling to lift two large bags of clippings and deposit them in her Mustang. The bags are so overfilled and top-heavy they look as if they are ready to split at the seams. Just as my father starts to toss them, the top bag explodes like an overstuffed Mexican piñata, and everything rains down on him at once, covering him in dirt, leaves, branches, and debris. It is like a scene out of a slapstick comedy. Esther and I giggle under our breath. Suddenly Dad blinks his eyes open. After he wipes away the grit, he hollers comically, “Lor-en-zo!”

Esther and I start laughing, and Dad does, too. He realizes the silliness of the moment and embraces it.

Lola has never had any children herself, and so she always treats me like her little prince any time I visit. In fact, she gives me the book The Little Prince to read and is always encouraging my imagination. When I turn five, she takes me to Disneyland, introducing me to all of the great Disney fantasy characters. Her property is expansive, with clusters of big and small trees she calls her “Enchanted Forest.” I find it all very enchanting indeed, spending hours there with her, taking long walks with her through the forest. I discover empty Coke bottles and leave messages in them in the trunks of those trees. Every time I go back to Lola’s with Dad, I want to see if my bottled messages are still where I have left them. One message I write to Pinocchio asks, “Why does your nose grow?”

One time, to my astonishment, a message I left is missing. “Lola, where did the message go?” I ask.

“Pinocchio took them,” she says, enchantingly.

I have all these foster people in my life—Emmy, who fills that maternal need, and then Lola, who is like the grandmother I never had. My parents are busy and distracted, and so I am very lucky to have these loving people spend time with me growing up, giving me good advice and helping me realize there is no limit to what I can accomplish. I feel so fortunate to have such guiding help from people who have my best interests at heart.

Dad sells his Alfa Romeo and is soon driving a gorgeous red-leather-on-black, four-door Jaguar Mark X sedan. His new toy for the moment, he drives it everywhere. It is so luxurious he can never get enough of it. One day we are heading home on Sunset Boulevard after he picks me up from school—I am six years old at the time—when suddenly we hear the sound of a bad blowout. We assume somebody’s tire has blown.

“Boy, that’ll be one unhappy amigo when they find out,” Dad jokes.

Just as he says that, kerthump, kerthump, kerthump. The sound grows louder. Dad realizes the person with the flat is him. He is very unhappy about it, especially after just joking how some other poor amigo must have blown his tire.

“Wonderful!” Dad moans. “Just my luck.”

We are near a blind curve on Sunset Boulevard. Dad quickly pulls over and jumps out. The left rear tire is flat. He walks back to my side of the vehicle, picks me up, and sits me down on the grass to play with my Hot Wheels away from the traffic while he jacks up the car to change the tire. Before doing so, he smartly grabs two emergency flares from the trunk. He lights them and puts them out in the middle of the street to alert drivers as he changes the tire in the face of oncoming traffic. With a speed limit then of twenty-five miles per hour, drivers have plenty of time to change lanes and go around us.

Dad is busy changing the tire while I am busy playing. Suddenly, he hollers, “Look out!”

Loud screeching of tires as Dad hurdles over the back of the Jag, lands and rolls, and ends up a foot from me on the grass. Then Kablam! It sounds like a bomb going off. We look up. Dad’s Jaguar is suddenly in the middle of Sunset Boulevard. A small red MG convertible has plowed head-on into its trunk. The driver, who is racing another car down Sunset in the lane next to him, doesn’t see Dad or his Jag until the very last second. By then it is too late. Meanwhile, the other car races right past us, never stops, never waits to see what happened.

Thanks to his swift reaction, my father avoids being sandwiched between the Jag and MG and emerges unscathed.

“Are you okay, amigo?”

I nod as Dad slowly rises to his feet and walks over to assess the damage.

“Yeah,” I tell him as I start to stand up.

Dad’s eyes nearly pop out of their sockets at what he sees. He throws his hands in the air as his voice goes up an octave like Desi Arnaz moaning, “Ay ay ay!”

Now buried inside the trunk of his expensive Jag is the MG, its back end sticking out where Dad’s imported sedan once ended. Worst of all, the driver and his passenger are unconscious. Dad quickly says to me, “You wait here,” and takes the flares from the curb lane to the middle of the street to divert oncoming traffic around the crash site so he can pull the drivers out of the wreckage.

“What happened?” the driver asks groggily.

“I was going to ask you the very same thing,” Dad says. “Didn’t you see my flares in the street?”

The man shakes his head and as Dad moves him, he winces in pain. He looks as if he hit his head on the dash and suffered a concussion.

“You okay?” Dad asks.

“No,” the man says. “I feel as if I just went up against a three-thousand-pound gorilla and the gorilla won.”

Just then, the passenger awakens. Blurry-eyed, he looks over at the driver as Dad finishes pulling him out. “What happened?”

The driver says, “That’s what the man here is asking us.”

The passenger’s eyes get as big as saucers as he screams, “Oh my God, my MG!”

“Your MG?” Dad asks.

The driver says, “He owns the car and let me drive it.”

“Amigo,” Dad says with a laugh, “you just totaled my brand-new Jaguar Mark X and you are worried about your piece-of-shit MG?”

Under different circumstances, my father would have taken on both of them at once. Instead, he holds back as a police squad car pulls up behind them. An officer gets out and asks, “What happened here?”

My father smiles. “Ask them. That’s what I’ve been trying to find out.”

Within minutes, an ambulance is on the scene, and shortly after that two tow trucks come to haul off my father’s Jaguar and the piece-of-shit MG that now really is, well, shit. The story has a happy ending. With his insurance settlement, Dad buys himself a new Jaguar XKE convertible but after that avoids that blind curve on Sunset Boulevard and is wary of MGs anytime he sees one on the road.

Every life has its changes, of course. Unfortunately, my changes are often extreme. After Mom divorces my father, the men come in and out of her life as though through a revolving door. We move around so often I change schools five times in eight years; it seems I am constantly leaving old friends and trying to make new. It is all very unsettling for a six-year-old who is seeking nothing more than normalcy in his life. As crazy as it seems at the time, it will prove good preparation for my career as an actor. And I believe it is why I become so reserved in my emotions, always ready to enjoy my life but without revealing much. But that’s later; this is happening to a six-year-old child.

In December 1963, Mom separates from Christian, and in October 1964, she ends her unhappy four-year marriage to him. Mom claims he “showed no interest whatsoever in home or family life.” As she says, “It was impossible to have a normal life with him.” In the divorce, which is an ugly affair, the judge awards Mom the Pacific Palisades home where I grow up, plus $25,000 in $500 monthly payments and a percentage of his oil stock holdings.

During and after my mom’s divorce, my friendships mean everything to me. My friends are my refuge, my solace from the tumult in my life. Most are regular kids in the neighborhood, including my first girl crush: Laurie Hayden, the daughter of well-known actress Eva Marie Saint and producer-director Jeffrey Hayden (who later directs me in a couple of Falcon Crest episodes). The couple also have a son, Darrell.

Laurie and I become friends due to the blossoming friendship between Emmy and the Haydens’ black nanny, Bea. Emmy takes me to play with Laurie at the Hayden house while she and Bea gossip in the kitchen. Laurie, who is my age, seven, has the brightest red hair and the sweetest smile. I quickly develop a crush on her. We play in the pool out back, and I find her irresistible.

One day Bea brings Laurie with her to our place to play in the backyard tree house Dad helped me build. Laurie is a little scared as we climb up to the tree house. It is Laurie’s first time, and so I help her up and then climb up after her. We sit next to each other and we play with my Hot Wheels and G.I. Joes. Suddenly I look at her. I feel this strong impulse to do something.

“What?” Laurie says.

Impulsively, I ask, “Can I kiss you?”

“Maybe,” Laurie says coyly.

“When?”

“Not now.”

“Well,” I persist, “when?”

“I don’t know.”

Climbing down from the tree house, I wait for Laurie at the bottom, extend my hand to help her, and still hope to kiss her. I follow her around the backyard like a love-struck puppy. We meet at the swing set. She gets on a swing. I get on a swing. Now we are both swinging. Laurie stops after a while and gets off. She runs over and lies down on the grass under the huge maple tree. I run over and lie down next her. It is late in the afternoon. We have this epic view of the sky above. The sun is golden. Leaves sway on the branches as a cool ocean breeze ripples through them. Our heads are close together. Laurie suddenly looks over at me and says, “I guess it’s okay for you to kiss me now.”

I kiss Laurie on the lips. The kiss happens so fast and lasts only seconds. Immediately I feel tingly all over and think I am in love. I have no idea what love is, of course. I just know that kissing her feels right. The feeling is short-lived. We never kiss again but remain the best of friends after that.

In 1965, Dad and Esther finally move to a place of their own. They buy a tear-down at 11011 Anzio Road in Bel Air, damaged during the famous Bel Air fire of 1964. They purchase it for cash, and Bill Pereira, an architect friend of Dad’s, then redesigns and rebuilds it. The finished property includes an Olympic-size pool out back, since both Dad and Esther (naturally) love to swim. Yet anytime I visit the house I feel like a guest. I never for a moment feel like part of the family. Esther, Dad, and her children from her previous marriage are “family” and I am just their houseguest.

Afternoons after Dad picks me up from school, he and Esther usually swim. It is all new to me, as I never remember them swimming at Lola’s place. And I certainly don’t remember the way they swim: completely nude. The first time I experience it, Dad says to me, “Go into the house and don’t peek.”

“Oh, okay,” I respond.

As a seven-year-old kid, I know this is weird. On one level I understand, yet, on another, I know this is not something every kid should experience. Not until I grow up to become a parent do I realize how weird it really is.

I do as Dad tells me. I run back inside the house, grab a snack in the kitchen, and watch a little television while they swim naked in the pool. Curiosity finally gets the best of me. Like any kid, I do exactly the opposite of what I was told. I peek to see if they really are naked. After all, Dad said, “Don’t peek,” not “If you peek, you’re in trouble.”

I walk over to the living room window facing the pool, pull the curtain off to the side, and peer out. I cannot believe my eyes. Sure as shit, Dad and Esther are swimming in the buff. They are swimming laps as if they are training for an Olympic event, only naked. I find it too fascinating to stop looking. Next thing I know, Esther steps out of the pool au naturel. I cannot take my eyes off her. With her luscious, languorous locks of hair and curvaceous, robust figure, she is like a goddess standing there as she towels herself dry. Soon she disappears into their bedroom through a sliding-glass door off the patio, and my flirtation with the goddess is over as quickly as it started.

Next, Dad gets out. He is very much the man I imagine him to be, with a trim and athletic physique that complements his manly package. For a second, he looks my way. I shudder at the thought of him catching me. Fortunately, he doesn’t see me. He picks up the other towel off the chaise lounge, dries off, and joins Esther in the bedroom for a very long time, like a half hour. I go back into the living room to watch television. It’s getting close to dinnertime, and I’m getting hungry. In the meantime, I walk into the study adjacent to their bedroom and start my homework. The bedroom doors are still closed.

Suddenly, Dad appears right behind me. I turn and look. He is standing there naked with a huge erection. Never in my life have I seen anything like it. I am this seven-year-old kid, a guest in my father’s home. Still learning the ways of the world. Still trying to figure things out. And now my father is standing there as if nothing is wrong, his corn dog sticking in my face as I try not to stare.

“Hey, amigo,” he says, “you must be getting hungry.”

I avert my eyes away from Dad’s big salami. “Yeah, a little,” I mumble. I’ve watched National Geographic specials and stared at enough pictures in magazines to know what penises look like. Dad’s, however, is beyond my comprehension.

I add, “I was wondering when you guys were going to come out.”

Dad carries on like we are having a normal conversation, as if nothing is out of the ordinary as his flagpole still stands at attention. “We took a swim, amigo,” he says matter-of-factly. “Esther is taking a shower and then she is going to start dinner.”

I can only think of one thing: “Wow, is that the way I am going to be? I hope so!”

The fact Dad is so well endowed makes me realize later why women loved him and put up with his shenanigans. As the years went on, I never mentioned the incident of the erection or its effect on me. I do ask once, much later, “Did you ever play around on Esther?”

And Dad says, “I never fooled around on Esther.”

“Nothing ever stopped you before with other people.”

“Well, with Esther, it’s different,” he admits. “She loves having sex and we do it a lot.”

I laugh. “Oh, thanks, Dad.”

“More importantly,” he adds, “she treats me so well I could never live with myself if I did anything to hurt her.”

It is a very mature thing for my father to say. Especially for the biggest corn dog in the studio system who, along with Douglas Fairbanks, had more tail than two of Gene Simmons of KISS fame. Simmons brags about how he has had two thousand women, but he has nothing on my father. Between his stardom in Argentina and glory days in Hollywood, my father had so much tail he easily eclipsed that mark.

As for Mom, now thirty-seven, romance blooms again and she is married for a fourth time, this time on Christmas Eve 1965, to Alexis Lichine, a prominent vintner and entrepreneur fourteen years her senior. They marry at Queen Forts House in Bridgetown, Barbados. His daughter, Sandra, who is a little older than me, and his son, Sasha, children from a previous marriage who continue to live with their birth mother in New York, are also on hand. Alexis, born in Moscow, USSR, seems like a fine fellow. He is refined, well spoken, well educated, and very ambitious, just like my mother.

In the beginning, Mom and Alexis maintain a bicoastal marriage. My sister, Carole, and I reside with Mom in Los Angeles while Alexis lives in two places: a beautiful Fifth Avenue two-story townhouse in New York and his lovely chateau at his world-famous vineyard, Château Prieuré-Lichine, in Margaux, Gironde, France.

I never really question the living arrangement Mom and Alexis have chosen. It is working, and of course, I love California, the beaches, and the weather so much I can never imagine leaving it, ever.

Despite marrying such a wealthy man as Alexis, Mom keeps pushing the envelope with her career. She writes a syndicated column that appears in some seventy newspapers and publishes a book on beauty care from a man’s point of view, Always Ask a Man (the book soon has three studios negotiating for the film rights). In addition, she makes countless personal appearances at beauty clinics.

Not until I enter third grade do I realize Mom is a celebrity. In March 1966 she pioneers a completely new concept in television with a daily five-minute show called Arlene Dahl’s Beauty Spot. It is broadcast on ABC affiliates between Those Who Think Young and Where the Action Is. She films sixty-five shows in four weeks and claims, “From now on I’ll work six weeks in the fall and six weeks each spring on the show and take the rest of the year off.”

Then I understand: My mom is famous. Then the reality really hits me: I will see even less of her now that she is. Later I am always happy that people ask for her autograph, but back then it has dawned on me that I have to share my parents with the world. They do not really belong to me.