Читать книгу Malaysia: A Travel Adventure - Lorien Holland - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMalaysia:

The Original Melting Pot

A typical village house in Kampong Mortem in downtown Malacca. Its steep pitched roof is well suited for ventilation and tropical downpours. The ceramic tiles on the steps are a Portuguese-influenced style.

Long before New York became the melting pot of the New World, Malaysia was bubbling away, mixing cultures, religions and ways of life. From way back in the third century BC, when trading links were firmly established with China to the east and India to the west, Malaysia has been a fertile ground for the fusion of different faiths and ways of life. The result is a unique jumble of localized cultures involving aboriginals (Orang Asli), Malays, Chinese, Arabs, Sumatrans, Indians and Europeans, who have mingled and fought for control of trading rights and the country’s rich natural resources.

Underneath that mesh of beliefs and religions, Malaysia is a humid, tropical landscape, where frangipani trees grow by the roadside, inviting white sands separate the land from the sea and the jungles are so dense that animal and plant species are still being discovered within. Encroaching on that landscape is, of course, a fast-expanding urban environment of office blocks, highways, billboards and shopping malls as the modern state of Malaysia reaches towards its goal of developed nation status by 2020.

I was quite unprepared for the degree of modernity in present-day Malaysia when I moved there in the year 2000. I had seen photographs of Kuala Lumpur’s icon to progress, the Petronas Twin Towers. My sister, a long-term resident of the city, had also briefed me on the changes afoot. But the state-of-the-art airport, the modern highways, the swish hotels, the highly air-conditioned upmarket shopping centres – not to mention the traffic jams – were way beyond my expectations.

Until recent decades, Malaysia, or Malaya as it was called in colonial times, really was a backwater. Time passed slowly, palm oil, tin and rubber were the major industries, and people had time to sit and talk – as long as they were out of the sun and in the shade!

Still, the concept of time passing slowly should not be confused with time not passing at all. Malaysia has a very lengthy past. Human remains dating back some 37,000 years have been found in the Niah Caves in eastern Malaysia. More recent ancestors moved southwards from China and Tibet around 10,000 years ago and make up the bulk of the indigenous populations of Orang Asli today. Later migrants brought fishing and sailing skills with them, and gave their name to the Malay Archipelago – lands which today make up the modern states of Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Brunei.

The Sultan Ahmad Samad Building at Dataran Merdeka (Independence Square) in the centre of old Kuala Lumpur. Once the centre of the colonial administration, the building now houses the commercial division of the High Court.

The pink granite Putra Mosque is at the centre of the new administrative capital of Putrajaya. Completed in 1999, the mosque can accommodate 15,000 people and is an interesting blend of Islamic architectural and decorative styles from Malaysia, Persia, the Arab world and Kazakhstan.

Malaysia’s geographical position at the crossroads between civilizations and trading routes meant outside influences were always strong, and often hard to resist. After the arrival of the Malays, there were four main waves of foreign influence and conquest, which eventually split the Malay Archipelago into separate political entities. This is not hard to understand when you see that Hindu India, the Islamic Middle East and Christian Europe lie to the west. To the northeast are Buddhist China and Japan; and the shipping routes linking them all pass right around modern Malaysia and through the Strait of Malacca.

Dancers holding the Malaysian flag at the annual National Day parade in downtown Kuala Lumpur.

An aerial view of the heart of Kuala Lumpur. The large green rectangle is Independence Square, once the heart of the colonial administration when it was known as the Padang. The mock Tudor-style Selangor Club is on its left and the Sultan Abdul Samad Building on its right. The triangle of green is the confluence of Kuala Lumpur’s two rivers and the point where the city started.

The startling variety of food in Malaysia is a good illustration of these differing cultural streams. From the majority Malay population comes spicy coconut and lemon grass-based cuisine. Southern Indian, Hainanese, Cantonese, Hakka, Javanese, Sumatran, Middle Eastern and Portuguese foods all have large followings. There is even the celebrated Nyonya style, which is a mixture of Chinese and Malay cooking. And every so often you’ll be offered a watery cucumber sandwich and a stiff cup of tea in a nod at British colonial rule.

The first major outside influence on the Malay-speaking world came from Indian and Chinese traders. The monsoon winds meant vessels had to pass down the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, round the tip and past what is now Singapore, and up the other side through the Strait of Malacca. Indian influence was particularly strong, and old documents speak of Indian traders buying timber and jewels from the Malays.

By the first century AD, both Hinduism and Buddhism were well established in these coastal enclaves, and Chinese chronicles speak of a great port in the Strait of Malacca in the fifth century AD. Two hundred years later, the maritime kingdom of Srivijaya rose to strength, and controlled the coasts of Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo. The maharajahs of Srivijaya waxed and waned, but stayed in power for 700 years by controlling the spice trade through the region.

Records of the time are sparse, but a possible early capital currently under exploration is Kota Gelanggi, in the jungles of southern Malaysia near to Singapore. Other outposts were in northern Malaysia, while most of the kingdom was focused on Palembang on the north coast of Sumatra. Srivijaya came under increasing attack from others who wanted to tax the lucrative spice trade. The fatal blow came in the middle of the fourteenth century from the Hindu Majapahit empire from eastern Java.

This is really the point where today’s Malaysian school children start their history lessons. A rebel prince called Parameswara escaped from Srivijaya when the empire fell and headed north, eventually establishing a coastal fiefdom around 1400. This was Malacca (Melaka in Malay), which quickly became the most important port in Southeast Asia, controlling the lands on both sides of the Malacca Strait and all the lucrative spice trade that passed through.

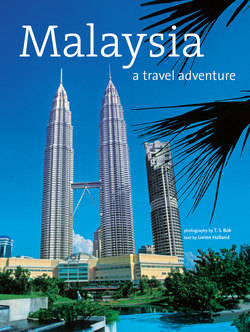

The record-breaking Petronas Twin Towers are Malaysia’s icon to modernity. Completed in 1998, they are eighty-eight stories high and were the world’s tallest building until they were eclipsed by Taipei 101 in 2004. The sky-bridge which links the two towers is open to the public..

The Kuala Lumpur Tower is the city’s telecommunications beacon, complete with a revolving restaurant at its upper levels. It is built on top of a hill and appears to loom over the Petronas Twin Towers. Views over the city are unrivalled on a clear day.

The port was the cultural lodestone of the archipelago, and when Parameswara converted from Hinduism to Islam in 1414, much of the region followed suit. What followed was the “golden age” of Malacca. The city deftly positioned itself to appeal to Indian, Chinese and Arab merchants, as well as all the local kingdoms. At the peak of its influence, some eighty languages were spoken in the city. To this day, the Malacca Sultanate is held up as the golden age of Malay self-rule.

But it was not to last. Tales of Malacca’s wealth and influence reached as far as Venice and made the port a prime target for the expansionist Europeans. A Portuguese expedition sailed from India in 1511, and after a month-long siege took the city. The last Sultan escaped and moved the court south to Johor. The port of Malacca then went into a slow but terminal decline, because the Portuguese did not have the resources to force trade to continue at Malacca. Muslim traders, in particular, started to use the port of Aceh across the Strait in Sumatra.

Johor, too, rose in significance, and the ousted descendants of the Malacca Sultanate finally tasted revenge in 1641 when they helped the Dutch expel the Portuguese from Malacca. But they were not able to rid themselves of the Dutch, who took firm control of the lucrative spice trade.

More than a century later, the British started to close in on the spice trade, first by forcing the cession of the island of Penang in 1791, and then by starting a trading post on Singapore in 1819. The British and Dutch then divided the region between themselves in 1824, with Singapore, Malacca and Penang going to the British and the rest going to the Netherlands. The political border has stuck to this day, with Malaysia and Indonesia divided by the Strait of Malacca to the west and the island of Borneo to the east.

The National Monument is a larger than life-size bronze sculpture commemorating those who died in Malaysia’s struggle for freedom, principally during the Japanese occupation in the Second World War and the 1948–60 Communist insurgency.

Malaysia is made up of a diverse collection of peoples and territories and makes a big deal of its diversity on National Day on 31 August each year. People dress in the national flag (far left), participate in musical and other routines (left) and parade in their regional costumes (below).

The armed forces and police take part in the National Day parade (above). Thousands of students, dressed in the colours of the Malaysian flag (bottom), also participate in choreographed formations reflecting the theme of the year’s independence celebrations.

Borneo holds much sway in popular imagination as the land of the head-hunters, exotic animals and deep jungles. Until the seventeenth century, the entire island (it is the world’s third largest) was ruled by the Brunei Sultanate. But increasing Dutch, Spanish and British control of the spice trade weakened the Sultan’s grip on power. An English trader, James Brooke, became the “White Rajah” of the southwest of the island, and a British trading company held sway in the northwest. The east of the island fell under Dutch control. Somewhat remarkably, the Brunei Sultanate survived and remains an independent state, albeit as a tiny shadow of its former self.

Brunei retains close financial ties to Singapore, which joined Malaysia some years after its independence from Britain in 1957 but was then expelled from the union and is now also an independent state. The other two parts of western Borneo are a part of Malaysia, along with eleven states in Peninsular Malaysia.

Those eleven states consist of the old trading ports of Malacca and Penang and an amazing nine sultanates, which are a reminder of the days when small kingdoms proliferated all over the Malay Archipelago, and there was no overarching central power.

To avoid renewed rivalries between the nine Sultans, they elect a head of state from amongst their number every five years. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong, or King, of Malaysia does not hold enormous political power, but is the ceremonial ruler of the nation, and is held in very high regard. The King’s palace in Kuala Lumpur, complete with red-jacketed guards on horseback, is very near my son’s school. He often asks if he can go and play in the lovely gardens, but I tell him that his only hope is to write a very polite letter to the King, because the guards would never let him through the gates. They are defending their King and their independence as a sovereign state, and not even a small boy wanting to climb the fruit trees can go in without an invitation.

A touch of paradise on Tioman Island, the largest island along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Virgin rainforest, a coastline ringed with bays of white coral sand and clear turquoise waters combine in sheer geographic splendour.

Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese community makes up around one-third of the population and is particularly noticeable in urban areas. The Chingay Festival in Penang is celebrated at the end of the year with dragon dances, as shown here, stilt walkers, acrobats, and decorated floats taking to the streets to the clashing of cymbals and the beating of gongs and drums.

Chinese New Year is a big festival in Malaysia and is celebrated with traditional lion dances. The Chinese believe that having a lion dance troupe perform at their homes during Chinese New Year and at newly opened business premises will drive out evil spirits and usher in luck and prosperity. The acrobatics of the agile "lion" as it twists, climbs, hops and jumps from stilt to stilt to the beat of huge Chinese drums, is a memorable and colourful sight.

Much of the central part of Peninsular Malaysia is a protected reserve called Taman Negara, which stretches over 4343 sq km (1,683 sq miles). This contains some of the world’s oldest jungles and is an excellent spot to experience the rainforest and see some of its diverse flora and fauna. Access is mainly by longboat (left), and attractions include an aerial walkway through the treetops (below right). The very lucky visitor might even spot a Malayan Tiger (below right), which appears on Malaysia’s coat of arms and symbolizes strength and bravery. However, the Malayan Tiger is endangered, with less than a thousand animals left in the wild.

Divers at Sipidan Island in eastern Sabah. Sipidan is Malaysia’s top dive destination, and one of the world’s best. More than 3,000 species of fish and several hundred coral species have been logged in its ecosystem.