Читать книгу Bad Blood: A Memoir - Lorna Sage, Lorna Sage - Страница 5

Introduction

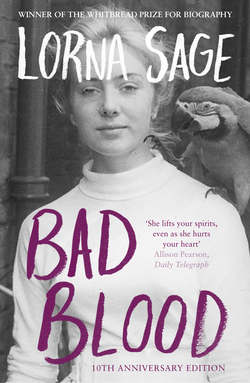

ОглавлениеWhen Bad Blood was published a decade ago it made an unlikely star of its author, the 57-year-old academic Lorna Sage. Sage was already well known to the small but important pool of readers who followed her literary criticism in both newspapers and academic publications, but this was something else entirely. Her account of growing up in a grubby Welsh vicarage after the Second World War, getting pregnant at 16, and claiming the education, career and life which no one – family, school or culture – thought should be hers became the surprise hit of late 2000. The book sold hundreds of thousands of copies around the world, won the Whitbread Award for Biography together with the PEN/Ackerley Prize for autobiography and made Sage famous to people who would otherwise never have heard of her. In fact it was all a bit of a fairy tale – ironic when you consider that one of Bad Blood’s chief concerns is to cast a sceptical eye over the stories handed to us in childhood to steer by, regardless of whether they fit or hobble us horribly.

And then, just as the excitement reached a crescendo in the midwinter of 2000–2001, this late-to-the-party princess was gone. She had been felled by a complicated collision of asthma, emphysema and a fierce smoking habit, which made her cruelly short of breath. It had, though, also granted her the privileges of the chronic insomniac to read through the night, a habit begun in her childhood when she had been made restless by the face-ache of severe sinusitis.

Sage had been named after the heroine of one of her clergyman grandfather’s favourite books, R. D. Blackmore’s Lorna Doone, and if her life proves anything, it is that reading can make things happen. Not just in the old clichéd way – scholarship girl grafts her way to a life her parents could never have provided – but in the sense of giving Sage a keen sense of how stories work to shape our knowledge of self and the world. And how, most crucially of all, if a particular story doesn’t make sense, then you must simply make up a better.

The irony of the timing of her death would not have been lost on Lorna Sage. Unusually for a literary academic steeped in the critical theories of the Seventies and Eighties that declared the author dead, she was fascinated by the connections between writers’ lives and their works. And as an expert reader of memoir she would have known that you seldom get the neat double ending of text and life that had so spectacularly occurred with Bad Blood. As a result the book remains eerily intact, because there is no author on hand to expand, provoke or riff on it. We are left, as readers, an extraordinary freedom to make of it whatever we will.

Sage had been working on a memoir about her early life for some time, but it was the discovery of her grandfather’s diaries in the 1990s that suddenly gave shape to the book: it came out quickly, and in such a finished form that virtually no editing was required. These were the diaries, of course, which her grandmother had used to blackmail Revd Meredith-Morris into handing over most of his stipend. Full of details of his joyless philandering, the diaries would have been highly damaging if they’d got into the Bishop’s hands, which was exactly where Sage’s grandmother was threatening to put them unless ‘the old devil’, as she called him, paid up and paid regularly.

Described like this, Bad Blood sounds like a parochial book, in all senses. Yet when it appeared in the early autumn of 2000 it was a national and international hit, as if people had been waiting for it without quite knowing why. Perhaps it was to do with the fact that the world was now embarking on a new millennium. The mid-twentieth century with its watershed war and the unprecedented social changes that followed was about to be left behind for good. Very soon all the detail from that time – ration books, the eleven-plus, council houses, the nascent NHS, rural buses – would slip from living memory. Here was a last chance to see that world at first hand from someone whose intellect was briskly contemporary – mostly, indeed, ahead of the pack – yet whose life and mind had been forged in another age entirely.

Bad Blood, though, is much more than a social history of the war baby generation (Sage was born in January 1943 while her father was still away fighting). It is instead a story of absolute singularity involving one of the great tragi-comic characters of contemporary English literature, the Revd Meredith-Morris of St Chad’s, Hanmer, a rural parish situated in that thick finger of Wales which crooks oddly into Shropshire. The Old Devil is there for less than a hundred pages but he manages to dominate the whole book, with his great gusts of unhappiness, his boozy self-pity and of course his random lusts, which include trysts with the district nurse and his teenage daughter’s best friend. It is the Revd Meredith-Morris’s Bad Blood that circulates through the narrative long after he himself is gone, tainting everything it touches including little Lorna whose growing appetite for boys and books is darkly attributed to her grandfather’s sticky, vicious bequest.

Nor is it just the people in Bad Blood who are particular. Sage locates Hanmer precisely in time and place, giving us a muddy, midgy rebuttal to any expectation that the tale we are about to hear will be a pastoral one. This is Britain in the last gasp of the tenant farming system, before agribusiness rationalised production into huge regional food factories. The mud is Flintshire mud, rich and sucky and good for beef, though bad for stuck wellingtons. There are big dirty labouring families complete with the obligatory daft son and rusty machinery that takes an age to get going. Few of Sage’s readers will have experienced any of this at first hand, yet her extraordinary achievement is to make us feel that this story is somehow ours too. So while you may not have spent your early years living on rations, you know what a sly punch in the playground feels like. You may not have worn the complicated underwear that was de rigueur for older schoolgirls in the 1950s but you know what it is to feel uncomfortable in your own skin. Hanmer may have class gradations that seem as quaint as anything from Jane Austen, but which of us does not recognise that feeling of falling foul of some social tripwire we were too slow to see coming?

Still, the last thing Bad Blood wants is soppy identification on the part of its readers. Indeed, one of the most bracing things about the book is Lorna Sage’s indifference to making us like her. This blonde princess locked up in the gothic vicarage has bugs in her hair not because of some extraordinary drama of neglect or cruelty but because no one can be bothered to do anything about it. Her gaze, she tells us, is shifty and her default state sly. Had you known her as a child she almost certainly would not have wanted to be your friend, nor you hers. There is nothing remotely cosy here. And any idea that Sage is writing a misery memoir or asking for our pity is simply obscene.

The great joy of the book – and it is a joy – remains the way that this comic nightmare is delivered in the cleanest and clearest of language. As Professor of Literature at the University of East Anglia, Sage was sometimes required to be dense in her academic prose but you can really feel her exultation when she writes, as she did in her much-admired reviews in the Observer newspaper, for the Common Reader. She had a huge admiration for those authors such as Anthony Burgess who hacked to pay the bills, and a corresponding determination to reach the widest readership possible. And her talent is gloriously on show here, with that miraculous ability to conjure the Hanmer landscape, tricky turns in Britain’s post-war social development, and the inside of a priapic vicar’s brain, all without boring or baffling the reader for a moment.

Despite her scepticism about the coerciveness of certain kinds of stories, Sage does give us a happy ending of sorts in Bad Blood. She tells us how her life played out in ways that are clearly a matter of quiet pride. The Bad Blood, it seems, had finally been faced down. There was, though, one bit of the story which her sudden death in January 2001 left unfinished. She had been thinking about her memoir for so long. Now here it was, an enormous hit, making her famous around the world. What would she have done next? Another volume of autobiography? A novel even? Or more of that brilliant literary criticism which seemed to crack open the world of contemporary fiction with such deceptive ease? We will never know now and that, perhaps, provides the most tantalising ending of all.