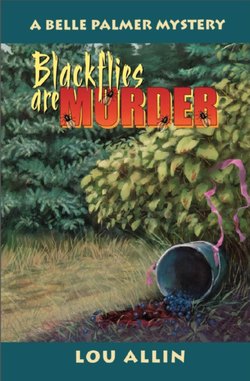

Читать книгу Blackflies Are Murder - Lou Allin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеWho cares if they pollinate the blueberries?” Belle Palmer mumbled to herself as she raked at the bloody crusts behind her ears. You could eat only so much pie. Damn blackflies. Would some genius ever invent repellent that wasn’t an oily, sticky solvent for plastic? Cheer up, they’ll be gone in a month, ushering in mosquitos, cluster flies, horse flies, moose flies, deer flies and pernicious no-seeums, which require a tent screen finer than silk. Welcome to Northern Ontario, where bugs are an equal opportunity employer: O positive is as full-bodied as A or B.

Belle usually avoided the woods until the hotter weather switched off the worst biters, but her German shepherd Freya was eager for a trek. The dog brought up the rear, browsing every ten feet for an educated sniff at her p-mail. Was it like reading a book? Tracing Braille? Red squirrels, the stunted northern variety, chittered teasingly from the cedars; foxes had scheduled night manoeuvers, littering the path with grouse feathers; and under the bracken, a rabbit hopped to safety, newly metamorphosed from white to brown in seasonal camouflage. Under the arms of a massive yellow birch, Belle spied a tiny, freeze-dried wintergreen fruit, popped it into her mouth and enjoyed a teaberry gum moment. She realized that she had stopped singing, a strategic mistake in bruin territory, especially when they were foraging frantically for tender grass, grubs, and roots before the berries arrived.

Suddenly her third-class human nose wrinkled. What a stink! Yet not cloyingly sweet like carrion. Rancid, sharp, even burnt. The dog had picked it up and veered off past hills of white trilliums and delicate ferns, leading her deep into the bush to a scene from an absurdist movie. Tied into the brushy alders were a dozen doughnuts—grape jelly, under examination—and stale. A lemon pie, ravaged by joyous ants, rested on top of a table rock. Miss Havisham’s wedding feast? Moving toward a glittery hanging object, Belle skidded to her knees, breaking her fall against a rotten log shining in the sun. Soaked with used fry oil, a generous gallon. The glitter came from a cheap plastic timer set with fishing line, Salvador Dali’s surrealistic contribution. No salt lick this, no appleyard for moose or deer, but an ursine smorgasbord. In its big-city wisdom, the Ontario government had cancelled the spring bear hunt. Someone was poaching.

Belle narrowed her eyes in disgust and rubbed her hands on the grass with dubious success at removing the tacky mess. The hunt itself posed no problem. Ontario had 75,000 of the critters, and rising. If a bowhunter or stalker offered fair odds, let them fill a freezer. Bear meat could be delicious in stews and savory sausages. It was the baiting that bothered her, ticket to the fifth circle of hell if she’d been devising poetic punishments for the afterlife. Rich Americans from Michigan, New York and Ohio tooled Lincoln Town Cars up to the distant lodges north of Sudbury and waved ever-inflating dollars. The scenario was simple. Set out tempting pastries, garbage or even rotten meat, then climb into a tree perch, rough boards or fancy metal frames out of the Cabela outfitter’s catalogue. Despite the morning frost, a pleasant wait with a few sandwiches, munchies, renowned Canuck beer or a mickey of rye, and presto, Bruno with insouciant pie face became an instant rug.

There was another motive more sinister than trophies—the burgeoning demand for ancient Chinese medicines based on animal parts, especially in Vancouver, where Hong Kong barons were enlarging their power base. Squeaky clean Canada’s shameful cousin to the rhino horn or ivory trade. And now that the loonie dollar coin had a new bimetal big brother (the twoonie, toonie, tunie?) featuring a polar bear, all the more ironic.

“Let’s get out of this reek. I don’t want to become a statistic.” Bear attacks were very unusual, but recently a female jogger in Quebec had suffered a fatal bite on the neck. Freya was, in sad fact, an insurance policy.

As Belle returned to the trail, she saw a familiar figure approaching, yelping beagle and loopy golden retriever heralding the procession. It was Anni Jacobs, who had cut and tramped these webs of peaty paths. A slight but vigorous widow nearly seventy, she forged out daily to impress herself softly upon the forests. Her unruly dogs earned no respect from Belle, but Anni’s late husband had prized these two for bird hunting, so she was coddling them into ripe old age. The women shared a reverence for the woods, yet respected each other’s privacy, passing a few words on the road at intervals. Childless, Anni devoted her spare time to volunteering at the Canadian Blood Services. Belle thought that she had better relate her discovery, for though the area was Crown land, Anni’s name was on it, so personal and firm were her footsteps.

Dressed in L.L. Bean’s prime chinos, a light anorak and a green net that covered her face, she greeted Belle as the Beagle barked mindlessly. “Didn’t recognize you at first. Life through a bug hat darkly. Haven’t trampled any of my early mushrooms, have you?” she said in a mock scold, raising the face net and bending to pull at the yellow roots of a clover-leafed plant with a white star flower. “I see our goldthread’s back. Pharmacopoeia of the woods. Aboriginals used the roots for cankers, sore gums and teething.”

“We have a problem worse than a toothache,” Belle said. “I found a baiting spot not far from that grandfather yellow birch with the lightning scar.”

“Should have suspected that. I heard gunfire Saturday morning, and more than one strange truck’s passed. It’s ruining the hiking. If I’m not ducking at a shot, I’m looking over my shoulder for bears straying from their territory, attracted to the free lunch.” A black look crossed the healthy old face. “Last week a mother and two cubs were foraging near the swamp. Bears don’t scare me, mind you, but I do want to know where they are. Likely they feel the same. Still singing George M. Cohen songs?”

“On the same two notes, just like Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Belle ran a hand through her short reddish hair, discovering a delta-winged deer fly looking for a home in the greying strands.

“I thought the spring would be safe now.” Anni bristled like a venerable porcupine at bay, a slight sag to one eye lending an arch expression. “Cubs are learning to feed with their mothers. Fresh from their dens and hungry. God knows enough of them get shot in the fall.”

“Where the quota is limited to boars, but who checks? Shouldn’t we call the Ministry of Natural Resources?”

“Overworked and underpaid, the MNR. Don’t-call-us department, if you can get through that phone maze. Press this, press that. And last week in town they tranquillized a mother sixty feet up a tree. Died in the fall and orphaned two cubs.” With her stout oak walking stick she prodded the Beagle’s rump to prevent him from poking his nose into an anthill. “Tell me where you found this hellish site.”

Frowning at the description, turning over possibilities like coins in her hand, Anni said, “This calls for extreme measures. I don’t suffer fools gladly. Enough is enough.”

“What are you going to do?”

With a conspiratorial grin, she ticked off steps on her wrinkled fingers. “One, search and destroy. Rip everything down and bury it. And I’ll give a good, solid burn to that oily log, safe enough before the dry season. Two, any strange vehicle up to mischief gets tires flattened or a spark plug tossed into the brush. They’ll get the message.”

“Uh,” Belle said, shifting her feet uncomfortably in consideration of the Russell belt knife at Anni’s side, “that could be dangerous. Especially if they figure out who did it.”

A wry smile teased one corner of the puckered mouth, as innocent as Lillian Gish’s in The Whales of August. “But, my dear, how can they? There are so many cottages. And I have a perfect disguise. The old are as invisible as children. You have to do what is right. And in the end, we’re all bear bait, and nobody gets out of the forest alive. Not even the bears.”

No arguments there, Belle thought with mingled admiration and uneasiness at the picture of a senior citizen guerrilla. “Please be careful. And keep me posted.” She watched the slender form stride down the trail, a five-foot challenge to osteoarthritis, one tough person, living alone twenty-five kilometres from town. What else to expect from a daughter of Manitoba, a rugged place where men are men and moose take precautions?

Back down Edgewater Road Belle walked, heeling the dog, alert to the sounds of approaching vehicles muffled by the hills, noticing, as she passed smoking barbecues and laughing children, that life on Lake Wapiti had shifted seasons. The varying sounds of motorboats had returned, a different tenor from the guttural roar of snowmobiles. On April 20th, the last ice floes had drifted out, and until Labour Day, the boats would hold dominion.

She turned at the Parliament of Owls sign that marked her driveway. Serving as personal totems were Horny, a foot-high brown owl with yellow marble eyes and threatening eyebrows, and Corny, his innocent snowy brother. Ever hopeful, Freya dug up a pebble and dropped it at her feet like a precious gem. Shepherds were notorious stone-swallowers. Probably the bouncing rock resembled some chaseable creature in a Jungian doggie symbol mindset. “Chip your fangs, but remember that you can’t get falsies. This isn’t Toronto,” Belle said, skipping the prize across the gravel and climbing to the deck where ruby-throated hummingbirds back from Gulf Coast condos duelled for a sugar fix from the bright red plastic flowers of the feeder.

Inside the two-storey cedar house, “Fireworks Polka” by Strauss was playing on the CD player, a lively treat with explosions of gunfire. Belle took a bath, talced up, and chose a T-shirt with a picture of Clayoquot Sound: “Pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth.” After pouring a glass of tankcar red wine, she opened The Toronto Star. Referendum, wheneverendum, neverendum. Would the Quebec dilemma plague Canada until the rest of the provinces joined the US along with the multi-cultural city of Montreal? Protection of Francophone heritage or just plain blackmail? Humiliated spouse or whining wife? Nervous ethnic and Anglo votes had tipped the last “Leave Canada” results to a narrow 50.6% NO victory, though the shenanigans with balloting resembled the Florida mess. None of this uncertainty was helping the confidence of the nation, interest rates, the stock market and Palmer Realty—her own gagne-pain—bread and butter.

Mealtime in a rush meant sensible Kraft dinner. Why were people so snobbish about the legendary blue box? Hard to beat the price, the convenience, the taste, or the plenitude, and the stuff was undeniably nourishing. Leftovers fried up into crusty magic. A salad of California red lettuce, artichoke hearts and green peppers rounded out the meal with a vinaigrette of balsamic vinegar and extra-virgin olive oil. Now there was a paradox. The satellite dish on the dock creaked to the American Movie Classic channel and brought Garbo’s growl in Anna Christie: “Gif me a viskey. Ginger ale on the side. And don’ be stingy, baby.” Between noisy bites, Belle mouthed the words along with the young prostitute and smiled on cue at the scene where Marie Dressler (a fellow Canadian from Cobourg), the archetypal barfly, maneuvered her bulldog face and bag-of-toys body, weaving a hand through a hole in her tattered sweater with drunken bemusement. “Know what? You’re me thirty years from now.” Had they really had an affair? The spate of kiss-and-tell books after Garbo’s death at eighty-five had been a gothic horror parade. Handstands after intercourse as a birth control method? Blasphemy. At fifteen, Belle had seen her first glimpse of the enigmatical ice goddess. Now, at forty-five and ten pounds over fighting weight, she was beginning to identify with Marie.