Читать книгу Bush Poodles Are Murder - Lou Allin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Six

ОглавлениеBelle drove to Jesse’s, one leg quivering from the adrenalin rush, pumping the gas with spasms. Her churning stomach had calcified into an expensive lump, bringing an acid reflux. Yet commiseration was out of the question. As if they’d last talked only yesterday instead of three years ago, the practical woman would eyeball her and calmly ask why, if she had suspected Brian’s motives, she hadn’t found a better excuse to avoid lunch.

Her planner sat open on the seat next to her, and she realized that she was ten minutes late for an appraisal twenty miles away. Pulling out her cellphone, she moved the appointment to the next day, citing vehicle problems, chastizing herself for letting life spin out of control. Passing a Ukrainian grocery and an onion-turreted Greek Orthodox church, she parked in front of 2267 Eyre Street on the old west side, a history lesson in early Sudbury, compact, no-nonsense dwellings hunched four-square against the cruel north winds. Jesse’s two-up, two-down home had a lurching glassed-in porch. Mossy shingles edged the mansard roof where snow had melted, and the front yard measured in arm spans. Tucked in the narrow lot behind was a treasured herb garden, lovingly tended while Jesse’d been away by pensioner Gino Teolis next door.

Wary of the slippery, uneven wooden steps, Belle entered the enclosed porch. Beside a lumpy, plastic-covered sofa, which creaked on rusty rockers, she spotted Jesse’s prized mukluks. She bent to stroke the soft leather, delicate beading and quillwork, the greeting of an old friend.

“Hellooooo,” she called loudly as she entered the compact living room, remembering Jesse’s hearing problems. Behind were the kitchen, bathroom and a work room, the two bedrooms upstairs in “Siberia” with the temperatures of a meat locker thanks to the underpowered and fumy forced-air oil heat. Shelves in the living room were crammed with Jesse’s sculptures. Over twenty clay masks, some decorated with feathers, acorns and leaves, gazed down from the walls. One trio, maiden-mother-crone, had won first prize at the La Cloche Art Show on Manitoulin Island. Piles of boxes testified more to the old woman’s general laissez-faire about neatness than to her recent return. Faded magazines and yellowed newspapers often waited for decades until she delved into them for a timely article.

A moment later, Belle heard a slow pounding on the steps from upstairs, and a huffing heralded Jesse Schoenberg’s arrival. Belle peered in wonderment. Was there such a creature as a Jewish witch? Jesse had shed years abroad in the fruitful desert. The tan helped, as did the dark hair, tightly crimped. At her age, it must be white, but Belle had never noted anything but varying shades from Irish setter to oxblood.

One of the University of Toronto’s first female graduates in physical education, a gym teacher before marriage, Jesse towered over Belle and carried twice her weight. She enveloped her young friend in a massive bear hug, her Norwegian sweater faintly redolent of lilac, the stiff ribs of her “foundation” buttressing her. Then she plucked a giant tissue from her sleeve and blew her large beak with a honk. “I might as well write my obituary, or maybe you can. This Gulag will be the death of me.”

Belle grinned for the first time in days. “You’re a miracle on two legs.”

Over glasses of hot tea sucked through sugar cubes, she told Jesse what had just happened. “And I forgot an appointment.”

“Small wonder, with that goon you described. Ver geharget. May he get himself dead. And you aren’t to grow an ulcer about dear Harold’s business. You can brief me, and we’ll open at the crack of dawn. I’ll hold the fort.”

Soothed by the tone along with the comforting clichés, Belle relaxed in an overstuffed armchair with scratched mahogany trim, its satin arms worn and nubbly, the lacy antimacassar tatted even before Jesse’s birth. The coffee table held a selection of dates and figs from Jaffa, along with a soft alpaca scarf, Belle’s late Christmas present. “And I don’t have anything for you,” she said mournfully, rubbing the soft wool against her cheek. Then she hunted up her coat and probed the breast pocket, retrieving the grouse feather, which she presented. “I wish I could pay you, but Miriam will need . . .”

Jesse tickled Belle’s chin with the feather. “It’s perfect for my Puck mask. Now shush. Stop feeling sorry for yourself. Needs, wants. Don’t we have enough? A jackpot could be around the corner. Remember that time at Sudbury Downs when I won . . .”

They laughed together. Instead of buying a new furnace, Jesse had splurged on a trip to Hong Kong, spending a week at a monastery on Lantau Island, eating vegetarian meals and sketching the carved spirits which decorated the roofs.

“Where’s the Bonneville?” Belle asked, tasting a succulent date more from hospitality than hunger.

“Gino’s tuning it. Drained everything and kept it on blocks in his shed while I was gone. What a man. Maybe I should consider a second marriage.” She ran large, knobby fingers over a dusty clutch of five-year-old magazines. “But then I’d have to clean. And nothing has changed since I left, even the Prime Minister.”

“Maybe his wife can convince him to retire. No one else can,” Belle added, her humour reviving as fast as the rose hip tea warmed her bones.

With Jesse in charge of the office that week, resurrecting old friends to review their realty needs, Belle called the hospital and was assured that Miriam could see visitors. On the following Monday morning, she turned left at the double snowflake complex of Science North, passing the new mega-hospital, now seventeen million dollars over budget, then the gleaming metallic buildings of Shield University, all gathered on the shores of Lake Ramsey. Upper level professionals cantilevered their designer homes along the beaches and rocky cliffs, absorbing five-figure tax bills. Very few unimproved lots remained in what once was cottage country, but at one hundred thousand dollars per fifty feet, they were money in the bank for the owners.

Though on her first visit she had merely dropped off the small suitcase, now she had time to survey the old brick sanatorium, its name a relic of the former tuberculosis institution on site. Renamed as the Northeast Mental Health Centre, the hospital sat surrounded by groves of pure white birch, peaceful and still, except for the occasional muffle of an early snowmobile on the newly frozen lake. A C-shaped set of bungalows housed a special First Nations treatment area. In front of the main doors was a weatherproof gazebo with a picnic table where smokers gathered, oblivious to the frigid temperatures.

Across from a small tuck shop called the Dandelion Café, she checked in with a blue-haired, pink-smocked volunteer at reception. Given Miriam’s name, the woman consulted a short list and then asked for identification. “Is Dr. Parr here today?” Belle asked, flashing her driver’s license.

“Take the elevator to the right to the third floor. He’s often in the lounge at this time. Can’t miss him.”

Belle followed her directions, and shortly after, entered a large room with huge windows, homey furniture, and a kitchenette. A fifty-inch television was partitioned off with soundproof panels and several armchairs. In front of a huge aquarium, a Hobbity figure traced a finger along the glass, attracting the wide-eyed attentions of a blue and yellow discus. Except for the white lab coat with a plastic pocket protector, he might have been a seventh grader.

“I used to have fish,” she said by way of introduction. “When they got too big for the tank, I donated them to Science North.”

“Ted Parr,” he said, shaking her hand warmly. “You’re here to visit a patient, I gather.”

Belle nodded, following the trail of a prehistoric plecostemos scouring the glass like a diligent janitor. “Miriam MacDonald.”

He flopped onto a sectional sofa and patted the seat, fixing her with a broad smile. “You’re Belle. Miriam has told me so much about you.”

Joining him in embarrassment, she made the obligatory sounds of humility. On cursory examination, Parr seemed barely thirty, with smooth baby skin, short brown hair, and one discreet gold earring. Yet the wisdom of his jade green eyes creased with laugh lines added years. His voice strong but sensitive, he betrayed no clinical confidences, merely assured her that Miriam would be glad to see her. “Keep the conversation upbeat,” he advised, picking up a clipboard as he looked at his Mickey Mouse watch. “She’s fragile, despite her bravado.”

A door at the end of the lounge opened, and Belle blinked. Miriam seemed to have shrunk, or was it the loose outfit? Institutional food could be a turnoff. She should have hit Tim’s for . . . then hot tears ran down her face as they embraced.

Belle looked into Miriam’s eyes, shadowed but unwavering. “Frail” could never describe her friend, but ten lost pounds had done a number. She shuffled for words, feared that she might stutter. “How are the meals? I’m sorry I haven’t sent . . . didn’t bring . . .”

Miriam passed her a tissue from a handy box on the end table. “Wouldn’t you think of food before anything else? Let’s sit down. I haven’t been walking much.”

They chose two armchairs with a view of the lake. From wall speakers, a Brahms string quartet played softly. “At least the music is decent,” Belle said, proceeding one baby step at a time. Should she even mention Melibee?

“Ted’s idea. The classics are relaxing, at least to my age group. His sessions have helped a lot.” Her voice seemed vaguely slurred but under tight control. She wore cotton pants and a cardigan over a Shield University T-shirt with a toothy beaver brandishing a hockey stick. Miriam’s sense of humour hadn’t vanished, or was she merely prisoner of the random choices Belle had made when packing that suitcase?

“Do you need anything else from the apartment?”

“You did fine. Thanks for the clothes and quilting book. And those movie tapes.”

Belle knew Miriam loved mysteries, and in haste that night, without a thought about her criminal situation, had selected more than one tale of vicious murder.

Miriam held out one hand, straight except for a tiny quaver of the little finger. “Damn meds, a necessary poison, they claim. They give you something that makes you feel good when you have no right to. But every time I think about . . .” She swallowed and gazed toward the lake, where in the distance a cross-country skier forged along with a leaping black Lab. “My God! Where’s Strudel?” She choked back a sob. “What a mess I am.”

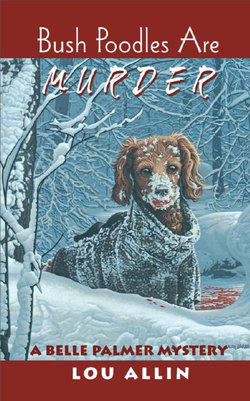

Belle passed her the tissue box. “Your poodle is at my place. Eating like a stoat, or is it shoat? Probably both.” She neglected to add that Freya had shown the pup the miracles of birch bark toys, and that the little dog had added the bulk to her diet. “I’ll keep her for as . . . until your cranky alter ego surfaces, Madame Hostie. Now here’s the good news. Jesse’s back in harness. No sub for you, of course.”

Miriam’s pale cheeks flushed, and she stared at the floor. “I’m ashamed to confess that I haven’t given the office a thought. What miracle brought her back from Israel?”

Belle made the sign of the cross, then switched to a complicated star of David. “Loaves and fishes to follow after the news at five. She’s already logged two old dolls who want to dump the monster houses now that they’re widows.” Untrue, but it coaxed a smile from Miriam.

Her eyes slightly pink at the corners but penetrating, Miriam took her hand in a rare gesture. “I didn’t do it. I couldn’t.”

“Of course. You’re all bark and no bite.” She squeezed back, tallying the evidence that Miriam had been deeply disturbed. Forgetting the job Belle could understand. Sometimes she’d like to do the same. But the poodle? Were there hidden depths to her friend that she didn’t want to probe? Who had killed Melibee?

At a nearby card table, where three people sat, a spoon clinked on a glass. A chubby woman in a sweater set with a string of pearls rose with a book in her hand. Lipstick had been clumsily applied in a clownish fashion.

“Poor lady. She does this every day at the same time.” Miriam whispered as she cocked a surreptitious thumb at the audience, one snoring Afro-Canadian man, a spaced-out teenager, and a thin woman playing solitaire, her mouth working like a hungry bloodsucker.

“Archibald Lampman’s ‘The City of the End of Things,’ 1895, a prophesy of environmental disaster. ‘Beware!’ ” the woman announced, clearing her throat. “ ‘All its grim grandeur, tower and hall,/ Shall be abandoned utterly.’ ” She paused and gestured toward a wall of grainy black and white photos of 1900 Sudbury, miners leaning on shovels by a slag pit, wooden hovels in the background and the rising smoke of open pit fires forming a hellish background. “ ‘Nor ever living thing shall grow, /Nor trunk of tree, nor blade of grass.’ ”

Belle observed quietly, “The Chamber of Commerce wouldn’t like this performance after the regreening campaign. Who is this woman?”

Miriam hid her mouth with her hand. “Bev Martin. High school English teacher. On stress leave in her thirty-fifth year on the job. Frankly, I think it’s going to be permanent.”

With the final post-apocalyptic image of the poem in her head, the abandoned town guarded by a “grim idiot at the gate,” Belle found herself applauding, along with a few appreciative patients.

Relieved for the moment at Miriam’s recovery, she returned to the office to find a banquet: chopped chicken livers, matzo crackers, pepper salad, and bananas from Costa Rica. “Union grown, of course. And here’s The Sudbury Star,” Jesse said, handing her the page with their ads. “I caught a typo. Something of interest on the front page, too.” Her wrinkled mouth twitched as she brought a steaming cup of herbal tea from an assortment of boxes by the abandoned coffee maker. Then she logged onto the computer, shoving Miriam’s foot roller aside with an annoyed look.

Belle gulped at the “beadrooms” in one listing, then unfolded page one. “LOCAL INVESTMENT COUNSELLOR’S EMPIRE COLLAPSES,” it read. “Less like a house of cards than a mountain of matchsticks.” Melibee Elphinstone, found bludgeoned to death (three words always used together), had been operating a variation on a Ponzi scheme, placating older suckers with largesse from new fish, the article explained. Aside from a few flyers in risky software companies reduced to penny stocks thanks to the tech implosion, the tempting portfolios he had amassed were entirely fictitious. Over one hundred people, mostly pensioners, had entrusted sums reaching over three million dollars. Marilyn Rice, seventy-five, said, “He was the son I never had. I mortgaged my home and gave him everything.” As for the penthouse, it had been rented, along with his powder blue Lexus, and even the furniture and art. Belle bit her lip until it hurt. Her friend’s savings were gone. One hope remained. A brief examination of his records led investigators to believe that some assets might lie in offshore bank accounts in Turks and Caicos, sunny, impoverished islands which a few years ago had asked to be annexed to Canada, a consummation devoutly to be wished as far as many were concerned.

She picked up the phone to call Steve for details and then decided to let him alone, declining to face another scornful refusal. Miriam would be released soon. What then? Between mouthfuls of the peppery pâté, full of minced onion and hardboiled egg, she summed up the situation to Jesse. “I know a few local lawyers,” she said, “but their focus is on civil cases, real estate lawsuits, not violent crime.”

“Funny you should mention that,” Jesse said, finishing a cracker with a burp and patting her mouth, leaving large cerise lipstick blossoms on the serviette. “My great-niece Celeste in Ottawa . . .”