Читать книгу Memories are Murder - Lou Allin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SIX

ОглавлениеBelle toyed with a pencil, its point dull as chalk. Yoyo had broken the office sharpener that morning and was off to Staples. She wasn’t that clumsy, just careless, wanting to do everything as fast as possible. As a multi-tracked Gemini and a minimalist, Belle understood the phenomenon.

“I knew you were concerned, so I read the files on your friend’s drowning,” Steve said, coming in the door and putting an attaché case on a table. “Detective Ramleau filled me in. Seems that the autopsy found alcohol in the stomach.”

“That’s not surprising. Mutt said that they found a bottle in his truck. But I didn’t want to believe that he’d been drinking.”

“Mutt. That’s some name. Only ever heard of one. Shania Twain’s husband.”

“Mutt’s a sweetheart. He’s very . . . sensitive. But strong.” She added what he’d said about the cheap brand.

“It wasn’t as if he were boozing all day. Nothing in the bloodstream. The liquor was raw. Undigested.” He leaned against the wall and sipped from an aluminum car mug.

Belle snapped her fingers. “So doesn’t it rule out his being drunk?”

“Let’s say he took a swig just before getting into the boat. Maybe he was coming down with a cold. As for the unusual brand, he could have bought it at some small outlet on 69 where there wasn’t any choice.”

“Any prints on the bottle?”

“Inconclusive.”

“I hate it when they say that.”

A glowering shadow came over Steve’s face. “It’s not all CSI, you know. Shows like that are perverting the legal system. Everyone wants DNA, hard evidence. Juries, like in the Robert Blake trial, aren’t convicting without it, even though witnesses testified that he solicited the killing of his wife.”

Tread lightly. Professional to his core and taciturn about his responsibilities, Steve usually dragged his feet on the details. So far he was being more than cooperative, perhaps because of her former relationship with Gary. “I see your point. Can you tell me more about the autopsy?”

“I’m only letting you in on this because it seems to be an accident, nothing more. No worries about compromising a case.”

Steve opened the case and passed her a photocopied file with scarcely ten pieces of paper. Was this all there was to a life? She scanned the jargon. Major contusions to head. Occipital bone reveals compound fracture and haematoma measuring six centimetres by ten centimetres. Bruising on ribs. Haematology was normal in the blood profile assays. No toxicology concerns. Victim has no appendix. Additional examination unremarkable. Cause of death, drowning. Lungs full of water. Pond water, not tap water. Daphnia. Other organisms she couldn’t pronounce.

Belle remembered when Gary’s appendix had been taken out. He’d been in pain for days but insisted on finishing his midterm exams, collapsing as he turned in his math paper. In trying to preserve his valedictorian status, he’d been half an hour from a rupture.

Steve took back the report. “So it appears that he fell. It would have rendered him unconscious, or at best too confused to save himself.”

Belle blew out a sigh. “Occipital?”

“Back of the head.”

“But in that case, wouldn’t he have been more likely to have come down in the boat?” With her fingers, she formed an area the size of the haematoma. A massive blow.

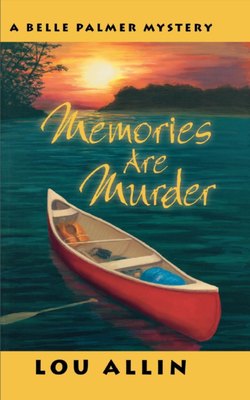

“Canoes are tippy. The fracture’s consistent with hitting the gunwale more than the seat. You’re letting your emotions carry you away . . . as usual.”

Belle bristled and tried to stifle a frown. “Can you make a few more inquiries? Accidents often aren’t what they seem in more ways than one. Think about that medical examiner in Toronto who misdiagnosed cause of death and sent parents and relatives to jail for killing children.”

Twenty seconds passed before a wry smile came her way. “Ramleau’s wife won a trip to Costa Rica, and they have to take it before July or lose the opportunity. Maybe I can muscle in and keep the case open. I wouldn’t do this for anyone but you. And don’t mention intuition, because your track record’s wobbly.”

Belle gripped his arm. “What a guy.”

He opened a small notebook and took a pen from his jacket pocket. “Now tell me everything you know about Gary, his partner, and what the hell they were doing up here.”

“For heaven’s sake, take a chair.”

“I’m used to writing standing up. Besides, my back is killing me. A whack of yard work on the weekend. I’m on my way to the chiropractor, as a matter of fact.”

Belle made a commiserative face. Dear Steve.

After he left, she pondered the simple words in the report. Unremarkable. She knew what it meant, but the idea stung. Gary had been anything but unremarkable. Wasn’t everyone’s son or daughter? At least he’d known a committed relationship. When the role was called up yonder, she’d check in as a dog’s best friend. Meanwhile, bills had to be paid. A lucrative apartment appraisal on Kingsmount was scheduled. Uncle Harold had been wise to suggest that she qualify for her appraiser’s credentials. It kept the place solvent in lean times.

Fifteen minutes later, the door opened, and Belle blinked. The woman of sixty plus wore Capri pants, which exposed sinewy lower calves with a roadmap of varicose veins, a loose paisley top, and battered flip-flops. Her hair was a thin nest of home-permed curls, unnaturally black with silver roots, and she wore mirrored sunglasses like a wizened trooper. She gave the room the once-over and clumped to Belle’s desk, tapping on it with a carved cedar cane. A cigarette dangled precariously from a cerise mouth sucked back into wrinkles. “You Belle? How ya doing? Yoyo around? I need a ride.”

“She’s . . . out for the moment. I don’t think we’ve met.” Belle fanned blue smoke from the air.

“Coco Caderette, her mother.” Beery fumes surrounded her like a cloud of fermenting barley. She leaned forward for a handshake, her fingers thin and cold as turkey tendons and her nails chipped.

“I can’t say when she’ll be back. Half an hour’s a guess.” Belle couldn’t help watching as an ash dribbled down the woman’s blouse. “May I call you a taxi? I’d drive you, but I’m all alone here.”

Coco guffawed, swiping at the blouse. “Oops, clumsy me. That reminds me of an old joke, honey. But shit, no. I can hitch down Notre Dame from here. Thumb, don’t fail me now.” Brandishing a digit gnarled with arthritis, as she turned, she noticed the picture of Freya on the wall, the noble sable head emerging from a greenery of ferns. “Gotcherself a nice shep. Female. I can tell by the nose. Very refined. À bientôt.” She lurched towards the door, leaving it open as she exited.

Belle blew a sigh of relief as she clicked the handle shut. No doubt there was quite a story in that family. Her own life was so uneventful, all the better for amassing funds on the march to retirement. Only lately had Gary’s return wakened her from her doldrums. Then there was the dumping in the bush. Would anything come of her report to CrimeStoppers? Maybe she’d been a bit hasty in putting up those pictures. Steve would have slapped her wrist.

She picked up the phone to check on her father, but the line was busy. As Belle listened to the weather, Yoyo returned, grinning broadly. “That place is as dangerous as Costco. They had a special on Turtles. Have one. So yummy,” she said, revealing a dozen luscious morsels.

Between nutty chocolate and caramel bites, Belle mentioned Coco.

“No sweat. I saw her get into a panel truck at the lights. Woman never needs a car. The North is so friendly.”

“It’s still not wise. Even though women of her age aren’t usually abducted.”

“Abducted? Maybe with a stun gun. Ma says she has a nose for people. Never wrong. Isn’t she a character? I love her to pieces. She’s my inspiration and the reason I’m not afraid to be a single parent.” Using a compact, Yoyo applied a fresh coat to her glossy red mouth, pursing her lips and giving herself an air kiss. She wasn’t using lipstick, but a kind of paint with a miniature brush.

Belle cleared her throat, speed-reading the sales slip and filing it. The candy must have been separate. Had Yoyo paid herself, or was shoplifting another habit?

Though Belle had enough discretion not to pursue whether Coco had ever been married or even supported by a man, Yoyo continued. “Old bastard took off thirty years ago. Mom had just lost her job as a cook at Burwash when they closed. Got another position at Pioneer Manor with the old folks. Damn, could she whip up meals. Vats of mashies. The bestest gravy. Homemade is nothing like that gluey, tasteless stuff that they—”

Yoyo’s phone rang as Belle was about to tell her to get back to work instead of reminiscing about gravy. Suddenly she craved one of the hot beef, turkey or chicken sandwich rafts that floated the North through winters.

The rest of the afternoon was quiet. Picking up a strawberry sundae from the convenience store on her way home, Belle stopped at Rainbow Country to check on her father. He dove into the ice cream as if he’d been starving, even though she knew dinner had already been served. Afterwards, dreading the truth, she checked his legs. A jungle infection. The blisters were oozing and broken.

“Still doesn’t hurt, though. They put bandages and cream on every day. The cowards look kind of scared. Am I contagious? Is it beri-beri? Remember Edwina Booth from Trader Horn? When they shot that film in Africa, she caught malaria and nearly—”

She took away the empty plastic container and spoon, her temples pounding. Belle hated making scenes, but enough was enough. “We’re going to find out. I promise.”

Down the hall she walked, choosing her words carefully. Passively accepting her father’s medical treatment had led to this crisis, but the staff wasn’t to blame. “Ann,” she said to the nurse at the desk. “My father needs to get another opinion. I think he should be in the hospital. Do you agree?”

“Cherie and I were going to suggest that,” Ann said with a relieved sigh as she picked up the phone. “I’m glad you’re insisting. The way the system works, the family has to make some healthcare decisions. Frankly, I don’t have much confidence in our Dr. Davison. If he had a decent practice, he wouldn’t have to pad his payroll with nursing home visits. Makes you think.”

Back in his room, Belle put an arm around her father’s thinning shoulder, once so muscular. She owed him the same care he’d given her, even if he had pinned her to a diaper once. Recalling how at only five she could twist him around her finger to take her for milkshakes made her glad her mother had tempered the spoiling with an occasional wooden spoon to her bum. “You’re getting a ride to the hospital. Someone will take a look at you. Let’s hope they have better credentials than Vonnie and Davison.”

“Will I get any food there? When will I come home?”

And Rainbow Country was home. “I’m not sick. I’m just old,” he’d grumbled when he’d arrived, an accurate assessment.

Still worried about the delay in her father’s treatment, Belle stopped at Mutt’s. The soft, warm June evening had brought him to a lounge on the covered porch, where he was sifting through a pile of papers. Gary’s massive pickup sat in the driveway. As she got out, he hoisted a beer. “One for you? Light okay?”

“Perfect.”

When he returned, she let a cool trickle run down her throat. Today had actually passed twenty-five Celsius. Who needed to live in the banana belt? “How’s everything going?” she asked, forced to lean backward in the angled chair until her neck muscles hurt.

“I’m just getting started. It’s weird, though. Gary always typed up his field notes within a few days. There’s nothing from the last two weeks. It’s as if he stopped working.” He shrugged. “Of course, I have his little pocket notebooks. He left a pile here on the desk. From the dates, it looks like the most recent one might be missing. His writing is terrible, though. Could be I have the dates wrong.”

“I didn’t see any small notebooks at the office when we picked up the supplies.”

“Maybe he had it in the canoe, and it’s at the bottom of the lake.” Mutt sounded discouraged.

She told him about the autopsy. “The details are pretty spare, but they’re always upsetting.” She recalled reading her mother’s death certificate. Everyone died from heart failure. The cause made the difference. A massive infection after chemo had triggered Terry Palmer’s final collapse.

“So I heard. Detective Ramleau again. Cold bastard. I didn’t care for his line of questioning.” He gave a disgusted look. “The jerk asked me about any insurance or wills.”

The thought hadn’t even occurred to her. Belle swallowed another few ounces and gave what she hoped was a contemptuous laugh. “That’s absurd. Are you saying that they’re investigating you?” Maybe she shouldn’t have pushed Steve to keep the file open.

“The old qui bono has them back on the case. Gary left everything to me. Double indemnity on insurance from the university.”

“But everyone needs a will. And accidents happen. Surely they can’t be—”

“He told me about it when we first got serious—$200,000 on the policy. Then of course our house in St. Catharines. A friend’s occupying it while we . . . I’m away. My name’s on the deed, though I didn’t contribute much. Gary insisted on making us equal partners. Everyone thinks writers are all rich, but I’m just getting started with a small press.”

“So that’s all, then?” She tried to minimize the totals, but the remains of the day would be considerable. Down south, especially in the Golden Horseshoe, house prices had gone to the moon. Half a million dollars bought an ordinary bungalow.

“He’d invested quite well. Mutual funds. All that stuff’s at home, though. I don’t know anything about the exact figures. Frankly, I never paid attention.”

Belle nodded. “Stocks fell into the toilet after 9/11, but values are soaring now.” Mutt waved aside the financial complexities. Was he that naïve? Still, not everyone cared for money as much as she did.

“So how bad was the interview?”

He seemed charged with anger and humiliation as he recalled being taken to a windowless cupboard of a room at Police Headquarters at Tom Davies Square, running long fingers through his thick hair, a pulse pounding in his temple. “I can’t believe they grilled me on where I’d been that day. And listen to my crime jargon. It might be funny if it weren’t so personal.”

“Routine.” Belle thought about the logistics of the trip north and spread her hands. “But you were driving 69 all the way, right?” Had he stopped off at Bump Lake? She felt guilty for her suspicions.

“I had no idea about how to get to where he was working. Why would I have cared until now? But the police say the road goes by the Burwash turn, and how can I prove I didn’t know?”

“I see. The point is that you could have reached him without much difficulty . . . if the time frame was right.” She noticed four hummingbirds duelling at the feeder. They were aggressive little creatures, territorial and war-like. Mutt must have filled it. That a murderer could mix hummingbird nectar seemed like a grotesque joke. “They sound like they’re bluffing.”

“It was beyond belief. They asked me some very intimate questions about our relationship. Whether anyone else was involved. Who was living in our house. A Cecilian nun from Zaire who’s taking courses in microbiology at Brock. Even the HIV/AIDS question lifted its ugly head.”

“How awful. Why is that relevant?” Trying not to be obvious, she scrutinized Mutt. With the modern drug cocktails, no one resembled the archetypal skeletal victim any more, but another crease had etched his forehead.

He squared his broad shoulders. “You can bet they wouldn’t have handled it this way in T.O. Bunch of rednecks.” He saw her grimace. “Sorry. I don’t mean you or any of the others I’ve met up here. Ramleau made my blood boil.”

“He’s off the case soon.” She told him what Steve had said.

“And this guy Steve’s a friend of yours? That’s a break.”

Too many ideas were arriving without notice. Belle didn’t know how to interpret that comment. Did he expect special treatment? She finished the bottle of beer, touched the cool glass to her cheek. Were the police right? Did Mutt have the opportunity?

Belle pointed at a road map he had spread out. “Show me where he was working. I know a bit about the region from my real estate travels.”

Mutt indicated Bump Lake, several miles west of the former Burwash facility grid, deep in a swampy area with a maze of dirt roads and old logging trails tapering into savage, uncharted wilderness. “Here’s where they found his canoe floating loose and his . . . body. His truck was parked a mile back at the turnaround.”

“So he must have portaged.” No wonder Gary had become so fit. Muscling even a light canoe was a task she couldn’t handle alone for more than a few hundred feet.

Suddenly he gave his head a pound with the butt of his hand. “Damn. I forgot about the canoe. Gary joked that it was his woman, sleek and fast. It’s a Prospector Chestnut.”

Belle knew that brand well. Old Town had been making them since 1910. “I have a Grumman. No mystique, but it can take a collision with a jagged rock. Anyway, we can use the truck and pick it up.” She paused. “Unless the police have it.” If it had been left in the open when the death had been thought accidental, how likely would it be that fingerprints or other forensic evidence like blood would remain? She kept quiet.

“Those Keystone Kops again. But then I guess you don’t get much crime up here, not like down south.”

“We kill people with roads. Sudbury has two of the worst twenty in Ontario.”

He looked at his watch with sudden embarrassment. “Sorry, but I’m expecting a call. I’ve been in contact with a few of his fellow professors at Brock. They’re excited about getting the notes and promised to answer any questions. If I can get this project tidied up, then at least I . . .” He looked out over the lake, where a merganser skidded across the glassy surface, its mate probably in the shoreline rocks and weeds guarding their nest. “Remember that baby elk? I dreamed about it last night. We should start there.”

The inadvertent “we” had made her a partner. She noticed a pile of periodicals on the table. One anomaly caught her eye. The Environmental Pollution Journal. It seemed well-thumbed and had strips of paper marking pages. “Pollution? I thought he was a zoologist.”

“Scientific disciplines often overlap. One time he did a study about metal levels in fecal pellets of moose. Around the ore smelters in Sudbury, I think.”

Once Sudbury’s core had been a wasteland the size of New York City, timber gone, vegetation scoured from roasting beds at the turn of the century and acid rain to finish the job. Soil had run from its hills, leaving black rock. Then in the Eighties, a government-industry-civilian re-greening initiative had brought rye grass and small pines back, leading to a United Nations reclamation award at the Earth Summit in Brazil.

“So question one, where is the baby?” Suddenly she had an eerie thought. Zoologists were quirky enough to keep carcasses in the freezer. Maureen had a power-chugging monster in the basement. “You didn’t look downstairs—”

He tapped her hand. “My first thought. It’s empty and unplugged. But I got a clue from a zoologist at Shield University. He said that Nickel City College has a dissecting room in their new tech complex. Paul Straten’s the contact name. Apparently he’s one of Ontario’s top elk researchers.”

“I gather you haven’t reached him yet.”

Mutt folded the map carefully. “We’re still playing phone tag.”

That night Belle ate a frozen pizza for a change. With a whole-wheat crust, low-fat mozzarella, and topped with spinach, it sounded better than it tasted. A call to Rainbow revealed that her father indeed had been ferried to the St. Joseph Health Centre Emergency Room. Ann suggested that Belle call to check his progress before driving in.

“He’s being seen by the doctor now,” the nurse said when Belle finally got through. “We’re full-up, but we’re going to keep him overnight, even if it’s on a gurney. Best thing is to call back in the morning.”

“Can you get him a sandwich?”

The woman laughed. “He’s already had three. Plus coffee, a doughnut and snacks from someone in the waiting room. He’s not allergic to peanuts, is he?”