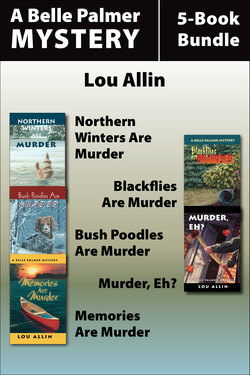

Читать книгу Belle Palmer Mysteries 5-Book Bundle - Lou Allin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SEVEN

ОглавлениеSix eyes beat two, so after Belle changed the plug, she drove down to Ed’s place, a winterized cottage which the DesRosiers had expanded and modernized after selling their bungalow in town. Rusty, their chocolate-red mutt, chased out to meet her, a deflated soccer ball in her jaws, running crazed circles around Freya, who treated her as an undisciplined but harmless juvenile. The short trip to the lodge would help the dogs burn off some fat; regular walks were rare in winter, and like humans, dogs compensated by overeating or begging scraps.

“Hi, Trusty Rusty,” she called. The bitch grovelled on her back in the snow and presented her pink belly in submission. Ed hated what he considered her feminine obsequiousness, but had been unable to break the friendly little creature of the habit. It was her nature to show this instinctive deference, Belle thought. To strangers, however, Rusty could present quite a performance of teeth and barks. Outside in the small oak trees Hélène had planted, bird feeders hosted a convention of colourful grosbeaks and a few robber jays. Freya jumped unsuccessfully for the suet ball and got a dirty look, so she ambled in innocence to her pal’s food dish and tried a few snatches. At the kitchen window, Hélène, hearty as her own tourtières and running perpetually in first gear, hoisted a coffee in pantomime.

Belle entered, careful to remove her boots to spare her friends’ new pride, a ceramic tile floor. Hélène was fiddling with a monstrous white apparatus that was humming and beeping. “Just taking this loaf out of the breadmaker. Bacon and cheese. Looks like it come fine.” She carved a chunk, slathered it with soft butter and presented it along with a mug of creamy coffee. “Shortbread if you want it, too.” Her hand tapped an industrial size pickle jar crammed with tiny pink, white and green trees decorated with silver balls and coloured sugar.

“My mother used to make these,” Belle confided as she helped herself, noting with shame that she had to drop a few to suck her greedy hand from the jar. Melting under her tongue, they took her back thirty years and gave a sweet blessing to the coffee. “Are you two up for a run to Beaverdam Lodge?” she asked.

“What for? Got a lead on Jim’s death?” Ed scratched his stomach thoughtfully, giving a self-conscious hitch to his pants.

“Sort of. Remember how we talked about Dan Brooks’ business prospects once the park went through? Well, apparently those prospects are already materializing. Some pretty expensive new machines from God knows where. I want to look the place over. Check for renovations. Let’s take the dogs. It’s only five miles.”

“We’re glad to go with you, Belle,” Hélène said. “I’m just sick about what happened to that boy.” She paused and glanced at the latest family Christmas picture magneted on the fridge. “Raising kids is a chancy business, a tragedy like this always so close. A car, a bike, even a fall from a swing.” Belle felt relief at her own single blessedness. Dogs were a heck of a lot smarter than kids, for the most part.

The ice was hard-packed with the recent traffic, and with the unusual humidity, ethereal patches of fog enveloped the many tear-drop islands, a water colourist’s dreamland recalling the Li River landscape. Periodically the trio stopped to admire the scenery and let the panting beasts catch up.

At Brooks’ island, a decrepit dock jutted out onto the lake, surrounded by a couple of pickups with knobby tires, four-wheelers for hauling supplies to the mainland a half-mile away via an ice road. Near the juncture of three popular trails, the lodge saw a lot of traffic, especially beer traffic, and more especially after hours. Official closing times were relative for Dan as were limits on the number of drinks sold. Even during the day, Belle had seen more than one driver fall off his sled passing her house. One machine had hit a pressure ridge at high speed, executed a barrel roll and tossed its lucky rider into a snowdrift before crashing upside down.

They slid up the glazed boat ramps in front of the lodge. A satellite dish rose nearly thirty feet high on a steel pole bolstered by cables. Perhaps this was the landmark which the pilot pulling up to her dock had been seeking. Neatly lined up near a path which led to the cabins sat four Arctic Cats, their paint scuffed and chipped. “These aren’t what Derek mentioned. In those sheds, maybe?” she suggested, pointing her mitt toward the back of the lodge.

Ed traced a fracture on one fibreglass hood. “Rentals are risky. I wouldn’t want some idjit handling my baby for any price. Not even Hélène. That’s why she has her own machine.” His wife aimed a less than gentle kick toward his leg, but he continued with a grin. “Like to throw a cylinder or wreck the track on bad ground.” He stepped aside as a large party of noisy snowmobilers walked past to the parking area.

One man yanked repeatedly on his starter in frustration. “ ’Course it won’t start, you dumbass. You left the kill switch on!” his friend yelled while his buddies slapped the back of his head and guffawed.

Give me the Burians’ little place any day, Belle thought. The Beaverdam was a circus. Old Pete Brooks had first built the lodge in the forties to cater to the fishing trade, but after the lakes suffered with acid rain, the trade had dropped off. Upon Pete’s death ten years ago, his son Dan had taken over. More friendly than ambitious, Dan hoisted a few too many with his customers and had let the place rot. One visit had been enough to turn Belle away. Now the situation had changed. The lakes were reviving, and so was the Beaverdam. This was no cheap facelift, but a regular overhaul, complete with Pella windows, insulated French double-doors, new siding and shingles.

“You dogs behave now. No biting. Here’s some jerky,” Hélène ordered as the animals licked their lips and cocked their heads as if they understood. They were friendly and safe enough outside on their own. The idea of tying a dog in such a situation would make a Northerner laugh.

The trio tucked their helmets under their arms and entered the lodge, stamping their boots perfunctorily on the broad oak boards. A cheery fire burned in the fieldstone fireplace, Pete’s pride, every rock lugged in his boat from the North River deposits. Stuffed pickerel and monster lake trout adorned the walls. Belle cast a glance at the additions which had tripled the size of the main room. Seating for an extra fifty at least. “Bucks” and “Does” were accommodated at the back, past a long, scarred bar stocking nothing fancier than Canadian Club. Most people drank beer anyway. Jars of pickled eggs and sausages sat by the cash along with chips and pretzels. It was quiet for late Saturday morning. The menu offered breakfast until eleven, so that was what they ordered. Very few places could screw up that simple meal.

“I miss Pete. Those days were the best. Plenty of fish in the lake, haul out five-pounders to fill our freezer. And no talk of that natural mercury stuff the Ministry keeps harping about now,” Ed said, rolling his eyes. “Not that I worry. Tastes the same to me. Ozone layer blown up, chemicals in the food, radon in the basement, we’re all goners.”

“I wonder if Brooks is still taking Americans bear baiting,” Hélène said, watching the waitress disappear into the kitchen. The common practice, disdained by purists, consisted of hanging rotten meat in a tree and bivouacking nearby, sipping a mickey of rye in a tree house until Bruno nosed out the gamey snack and went to heaven for his appetite.

“Salting deer and moose ain’t legal, but baiting is. Laws don’t make no sense. Bow hunting’s another thing entirely, but this is fish in a barrel if you ask me. I knowed a guy used doughnuts. Red jelly kind did the trick,” Ed said.

Hélène shook her head. “I hardly call that hunting. Murder more like. See any of that in our woods and I’ll tear it right down. ’Course, if the animals come knocking, it’s a different story.” A fine black bear skin hung on their wall from one spring afternoon when a young boar, just awake and foraging after its long nap, had smelled fish cooking. It had ripped out a window on its way into the kitchen. A handy shotgun was never far from the cottagers’ reach. The Ministry had fumed but admitted that 911 was of limited help against giant claws raking the cabin doors. Once in a while, for public relations, particularly if the offending bear were damaging property, officers from the Ministry of Natural Resources would trap one in a giant metal cylinder on wheels and relocate it a hundred miles north.

“There’s been some money put in here,” Belle said as she scanned the room. “Those windows don’t come cheap. That jukebox is new, so are the two video games and that big screen TV.” She consulted a folded card on the table. “Karaoke Night? We are getting very fancy here, folks.”

The waitress brought their eggs, bacon and thick homemade toast. Hélène’s eyes followed her as she moved around the booth, and Belle wondered at her interest, chalking it up to motherly concern. The girl’s skin was nearly transparent over her prominent cheekbones, her eyes ringed with dark shadow. Hélène touched her arm gently as she turned to leave. “Brenda?”

The girl’s face brightened. “Mrs. DesRosiers. I didn’t see you.”

“Working for your dad this winter?”

She nodded, pushing back her limp hair as if suddenly embarrassed at her appearance.

“Are you still writing stories about those Puddingstone kids? You were on to something there,” Hélène said.

The girl’s wan smile brightened her face. “Sometimes. Dad said I could take a course at the college next fall in between our seasons.”

“Brenda!” An irritated voice yelled from the kitchen.

“Nice seeing you.” She moved off, pausing to clear the next table quickly, the dishes clattering on the tray.

“Brooks’ daughter?” Belle asked.

“Slave,” Ed said. “He couldn’t run the place without her and the wife working like navvies.”

“How did you meet her?”

Hélène looked at her husband. “She went to school with our youngest son. Came to his graduation party must be three years ago and spent most of the time helping me in the kitchen, poor shy thing. Had a fancy to write a book about the Puddingstone kids, she called them. On St. Joseph Island where she used to visit her grandfather.”

Belle tapped her knife on the placemat with a map of Ontario. “On the way to the Sault. Now I remember. That pretty rock. Kind of a pink with dots of green and red like a steamed pudding.”

“It was a cute idea. It might have given her an escape from here and from her father. Doesn’t look like she’ll get the gumption to leave on her own. Best thing she can do is look for a husband.” She noticed Belle’s sniff and explained. “It’s quick and easy, and it often works. Sometimes a woman needs a knight.”

Coffees finished and the tab paid, they strolled the yard like confident, overfed American tourists. “Let’s find the septic system,” Belle suggested. “That’s where big money has gone. I count ten cabins, and the lodge, of course.” Over a small hill near a barn lay an expanse of undisturbed snow. A humming motor inside an open shed nearby caught their attention.

Ed rubbed his mitts together. “Big ’un all right. Listen to her purr. Sent all the way to Toronto, I’ll bet.” Behind hockey and fishing, septic systems were the third most popular topic on Edgewater Road. Requirements for a permit were stricter than the bar exam. People drank out of Wapiti, and no one wanted the water tainted by ancient cracked tubes to nowhere, well chambers made of rusted oil furnace drums and field beds flooded by bad drainage. The Boreal forest, with its thin veneer of peat over rock, made a good system costly. Building one required large excavations and tons of backfill. The tab for Belle’s house had run over eight thousand dollars. On the Beaverdam’s rocky island, the only option would be a so-called Cadillac installation where electrical power heated the effluent for more rapid breakdown and allowed a smaller bed.

Belle looked around furtively. “I’m going to check the barn. You two keep an eye out.”

She slipped into the weathered frame building while Hélène and Ed talked outside. In the back, under tarps as Derek had discovered, was a steroid brigade of powerful gleaming new sleds. Suddenly a whistle caught Belle’s ear and she slipped out a back door, just as a lean man in work clothes, a heavy red-checked shirt and insulated vest came towards them from the lodge. He was carrying an ice auger. “Help you folks with something? Need to rent a machine? Come in from one of the huts?” He motioned to the ice village off the point half a mile and lit a cigarette as the collies nipping at his heels exchanged canine courtesies with Freya and Rusty.

He gazed with interest at Belle’s tracks alongside the barn. “You don’t want to be walking off the paths. There’s all sorts of machinery and old metal parts under the snow.”

Belle answered with a sheepish smile, though she felt her pulse throb against her neck. “I was looking for that big yellow birch. Carved my name on it when my uncle brought me up here as a kid. You must be Dan. I’m Belle Palmer, and this is Ed and Hélène DesRosiers.” The men shook hands.

“I couldn’t help admiring the job you’ve done with this place. Looks like a million,” Belle added.

He drew slowly on his cigarette, then flipped it into the snow and grinned broadly, the proud proprietor. “Well, not really. Needed some fixing up for a long time. You folks from around here?”

“We live down the lake. Out this morning to exercise the dogs. Saw you had some rentals and wanted to tell our friends in town. How do you like the Cats?” Ed asked, winking at Belle as Brooks turned away to cough.

The lodge owner waved his hand in dismissal. “Oh, picked them up at auction down south. Nothing special. Good enough for the tourists, though, if you take my meaning. Don’t want to give them anything too new or fancy or it’ll be junk quick enough.”

“What do you charge?” grinned Ed.

He snorted. “Well, you know city folks. Sounds like a lot to them, seventy-five an hour. But five hunnert wouldn’t pay if they can’t handle ’em. How many times I’ve had to go carve those suckers outta the slush. Not supposed to go into the bush neither. Two Toronto fellas ridin’ double on the cheap broke down north of the lake last year. -25° that day. And they’s none of them had the sense ta carry even a match. Some old trapper saved their dumb hides. Make ’em take survival gear now, tarp, lighter, extra gas.”

Ed gave a hearty laugh. “Have to show them how to use it!”

Hélène had been checking her watch. She pulled on Ed’s jacket. “Come on. Someone has to get to town for groceries.” They left Brooks patting his dogs and casting an eye over his property.

While they rested at the half-way point, Belle pushed up her visor. “Somehow I don’t think he bought the story about the yellow birch,” she said.

“Maybe not, but you can bet he’ll get rid of those beauties you saw in the barn. Big business now. Star said yesterday there’s been over 230 stolen each of the last three years. Ship ’em off fast, though. Can’t ride a hot machine anywhere on the trail plan where there are wardens to check your permit. And a Mach Z’d stick out like a sore thumb,” Ed said, gunning his motor with his own digit.

That afternoon Belle called Mike Minor, the health inspector for the region, who stamped approval on every new septic bed. “Mike, I need some information about aerobic systems, like at the Beaverdam,” she said.

“Anaerobic, you mean,” he responded with a laugh. “What do you need to know?”

“How big a system would Brooks need with all those cabins? What would it cost, including backfill?”

“Pay attention now. I might ask questions later,” he replied. “I certified the whole shebang just before the winter. Must have struck it rich with the Super Seven lottery. Cost of the fill means nothing. Hauling it in by barge is the problem. ’Course, he has a Bobcat backhoe, so he does his own work. Still, you’re talking forty grand minimum with the ten cabins.”

“Where do you think he came by that money these days? Cashed in some insurance?”

“A lottery ticket’s his only insurance. I’ve had my eyes on violations ever since he took over from Pete and let the place go to hell. Nearly shut him down five times. Sharp-eyed boaters reported raw sewage was pouring into the lake one Labour Day weekend. An accident, of course. Nothing would surprise me about that fellow, but he’ll be as hard to catch as a century sturgeon. What are you getting at?”

“Not sure yet, Mike, but we’ll have a smasher when I get in a supply of Wild Turkey for you.”

Fresh with the information about Brooks, Belle tried calling Steve, but his answering machine took his place. She left a brief message, glad to avoid another lecture.

Come to think of it, Belle recalled, the lodge owner did look like a sturgeon, lean and mean and shrewd and primitive. Likely to bite off innocent toes dangling from a dock.