Читать книгу Eat a Bowl of Tea - Louis Chu - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

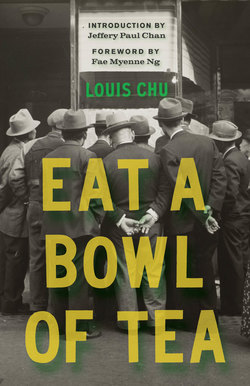

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеThe Wows: Wow Your Mother

FAE MYENNE NG

When Louis Chu’s novel about New York City’s Chinese bachelor society was published in 1961, I was starting kindergarten in San Francisco and just learning English. A decade later, when I wandered down the block to the City Lights bookstore and discovered his defiant, subversive novel, I didn’t just read Eat a Bowl of Tea, I inhaled it; I gulped it down.

What astonished me was how loud it was. I heard my whole world, the hatchet-speak of my great-grandfather working the abandoned gold mines, the seething courtesy of my great-uncle, the houseboy in San Antonio who later lost his business in the Watts riots, and the cursing of my merchant seaman father. I barely heard the hard-lined words held in the mouths of my army uncles, but I overheard the gutter cursing of my cousins and brothers.

In his sole novel, Louis Chu gave life to Toishanese, the dialect of those feisty and fearless immigrants from Toishan. He gave linguistic power to the railroad workers who not only blasted through the Sierra Nevada but also sliced out their own livers (the seat of love) to eat bitterness so that their descendants could carve a road into America and grow out a new soul.

My father could have been one of the men in Eat a Bowl of Tea. In 1941, he walked down Dupont Avenue in San Francisco as part of the 90 percent male population from Toishan. Toishanese men left home in droves to escape being killed. Over forty million had died in the Taiping Rebellion, probably a million in the Revolution of 1911, no doubt tens of millions in the Second World War, tens of thousands killed by the Japanese, and more tens of thousands who died in the Hakka-Cantonese wars, not to mention the many tens of thousands perishing in the endless natural calamities (famine, floods, typhoons; the bubonic plague killed nearly eighty thousand in less than a month). The natural and human-made disasters devastated the economy; crippling despair made the Toishanese especially vulnerable to the contract labor markets in America.

The bachelor society of Eat a Bowl of Tea escaped hopeless circumstances only to endure horrendous injustice in America. It’s no accident that the bachelors in the novel met every situation with a curse about death, dying, or killing. Go Die! Dead Man. Chop off your head.

If they had no actual power, they could at least control their world by cursing a fate worse than they could imagine; superstition staved off fear. Louis Chu used death-cursing to declare the bachelor society’s fearlessness in the face of hardship. He made language a shield against loneliness and death.

With the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, America enacted her first law to ban a nationality. It created the Chinese bachelor society. Only diplomats and merchants were legally allowed to bring their families. Married laborers left their wives in China; the unmarried ones remained bachelors because America’s antimiscegenation laws also applied to the Chinese. Today, on Chinatown benches across the country, old bachelors sit and wait for death—our national tragedy.

When Exclusion was repealed in 1943, the national origins quota limited the entry of the Chinese to 105 annually. No other race had a quota. This stayed in effect until 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act allowed for the reunification of families separated by Exclusion. But the damage was done. Grass Widows, those left-behind wives—if lucky enough to be reunited with their husbands—were often beyond the age of childbearing. My father called Exclusion a brilliant piece of legislation because it was bloodless. “America didn’t have to kill any Chinese. The Exclusion Act assured none would be born.”

Eat a Bowl of Tea is a manual on the brotherhood of the Chinese bachelor society. These men consigned themselves to never having an intimate family life, and their solace came from desiring more for the next generation. They were lonely but they were not morose. Louis Chu writes out how they survive their loneliness—with creative, unconquerable coolie spirit.

Wang Wah Gay runs the Money Come Club and has been separated from his wife for decades, the typical Exclusion marriage. He wants his son, Ben Loy, a waiter in New York City, to have a better marriage, for the couple to live together in America. Husband and wife fight at one end of the bed and make up at the other.

Lee Gong, a laundryman, wants the same for Mei Oi, his daughter in China, whom he has never met. The scheming fathers arrange for Ben Loy to travel to China, where the overjoyed mothers stage the first meeting. Ben Loy is smitten; Mei Oi is besotted. They have the traditional ceremony with a live groom (instead of a live rooster) and the marriage is consummated. But after they leave the village, the sex stops and the union seems doomed to be like all immigrant marriages, sexless.

In New York City, no one but Mei Oi gets laid. She hungers for sex and becomes consumed with getting it. Louis Chu created not only a temptress but a sexual adventurer, a devourer of carnal pleasure. Mei Oi is the erotic avenger, demanding sex as retribution not only for her Grass Widow mother but also for her fellow Toishanese—as in the actress Anna May Wong, who was both passed over for the Chinese lead in The Good Earth (1937) and prohibited from kissing a white actor on-screen because of antimiscegenation laws. Another Toishanese, James Wong Howe, was Hollywood’s most innovative cinematographer of the 1930s, but his citizenship wasn’t legal till 1943, and his marriage to Sanora Babb wasn’t recognized till 1948 (Babb was an ex-lover of Ralph Ellison and harbored unrequited love for William Saroyan).

Mei (for America) and Oi (for love) evokes American lovemaking. Honeymoon sex hooks Mei Oi and she craves it. Ben Loy becomes impotent, possibly from his whoring, while Mei Oi’s compulsion becomes an addiction. Ah Song’s “comic seduction” may be suspect, but his job is to be the seed dispenser; he’s her gateway screw.

Mei Oi is our free-loving flower child. Not hearing from her lover, Ah Song, she eyes her husband’s best friend, Chin Yuen, and flirts shamelessly and mercilessly with him. Like her Grass Widow forebears, Mei Oi is sexually ravenous. She craves the intimate touch, lusts for sexual attention and its rapture. Risking her marriage, she knits Ben Loy a green hat, broadcasting his shame of being cuckolded. Mei Oi will claim America by procreating.

Get laid, get pregnant, get power. Mei Oi’s womb is her gold.

In 1981, when I left for New York City, Eat a Bowl of Tea was the only novel I packed for my sojourn. Going east was like entering a new land, so I took the novel as my salve against homesickness.

Louis Chu was the first to bring the richness of Toishanese to the literary page. His novel has cadence, depth, and mirth: No can do. Go sell your ass. Sonavabitchee. Many-mouthed bird. Wearing a big hat? Pulling a big gun!

Its aim is as heavy and direct as a cleaver: [Ah Song] … the three-ply smoothie boy. Pretty butthole boy.

There’s literary invention: [Mei Oi] … was sorrowing over the abrupt termination of her brief honeymoon.

There’s imagination and action: Talking toilet news! Boiling telephone jook!

This next one can only be experienced live. Find a Toishan doy or a Toishan moi and ask them to read this: Nay gah do-do saang gai moe.

Watch and behold the true power of translation. Impropriety becomes endearing, betrayal becomes loyalty, and bitterness ends up a sweetness. Louis Chu not only preserves the rich, imaginative cadence of Toishanese but reveres its reticence and tolerance.

Arriving in Manhattan, I shared Eat a Bowl of Tea with my new New York friends: a Hong Kong–born, European-trained oboist, a conductor from Shanghai, a painter from Hangzhou, and a fourth-generation Chinese American, whose politically elite family had been immune from the effects of Exclusion. Every one of them was horrified and then baffled.

Wow your mother. Stinky Corpse. Fart drum. Sell your butthole.

“Why all these old men, and why all this vulgarity?” My new friends protested in shock. “This isn’t Chinese culture.”

“Wow.” I told them that this was real Chinese American culture, that their class upbringing had made them delicate.

“Wow your mother!” one shot back.

Another gained a fragile respect for the bachelor society. “I’ll look at the waiter at Big Wong’s differently now,” she said.

So we entered a new level of translation. They learned patience and I learned courtesy. What was birthed was the new Chinese American language, fearless and frugal, full of fight yet fraught, like our ancestors chiseling away on the Sierra rock face, tugging at the rope to be pulled up just before the dynamite blasted.

Welcome to Chinese America. Welcome to breaking up the English language and making it fully alive. Language is our gateway to power. Cursing was the way to break impotency. What the old bachelors didn’t know, they made up. What their progeny didn’t understand, they made up. Why not? This is our linguistic inheritance, language born of the unwelcome, words seeded to our long-standing imagination.

Why did the author translate “fuck” into wow? Did Louis Chu mean to sanitize wow, or did the publisher use wow as a censoring bleep?

I’d always heard the wows. For many years, my parents had a grocery store on Pacific, above bustling Dupont Avenue, and my mother kept a wicker chair in the center of the store for any old bachelor who wandered in. That chair was always occupied. (Now that chair sits empty in my writing room.) As a child, I was taught to greet each old bachelor as grandfather. I poured them tea and then stood by quietly, taking in their silence and their sighs and their explosive wowing. I consider that my first writing lesson; I honed language by listening to their hatchet-speak.

I intuitively knew the feeling behind every curse, so I never needed a translation. This linguistic passport is my birthright. Slipping along the edges of the bachelor society, the vulgarity gave me insight into the deeper hilarity. Humor is our medicine.

Eat a Bowl of Tea refers to the medicinal healing that Ben Loy trusts to regain his virility. The phrases 吃藥 eat medicine and 吃苦 eat bitterness are uniquely Chinese American. Through suffering, sweet life arrives. The ideogram for medicine has two parts. The radical, 艹, means grass and herbs. The root, 樂, means music, as well as happiness. Together they create the character for healing. Louis Chu makes music of Toishanese.

I like to think Louis Chu wrote a manual for our happiness, our health, and for our sweetness.

Writing Eat a Bowl of Tea had to be an endurance test. Louis Chu wrote the book under the double weight of the Exclusion Act and the Chinese Confession Program. Instigated by the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1956, the Confession Program’s intent was to ferret out paper citizenships (when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed the records at City Hall, my forebears claimed citizenship, as well as newborn sons, which were later sold as immigration slots for men to enter America, an ingenious way to circumvent the Exclusion Act). But its more subversive intent was to divert Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Communist hunt onto the Chinese. The program wasn’t eradicated until 1966, on the eve of the Summer of Love.

In Eat a Bowl of Tea, we feel the exploitation of the Red Scare and anticipate the explosion of the sexual revolution. Louis Chu is our renegade writer, withstanding Exclusion, enduring Confession, and perhaps pondering free love, to capture the terror of that climate as an unrelenting tension in his novel of bitter loving.

At its publication, Louis Chu was invited to appear on the game show What’s My Line? Because he was the fourth and last guest, it seems he might have been, as our forebears so often were, on standby. None of the panelists guessed his occupation as a disc jockey for a Chinese radio station, WHOM-AM. In closing, the host mentions Eat a Bowl of Tea. Louis Chu smiles, admirably courteous, admirably patient. His face is strong, yet humble. He has a boxer’s gait as he moves across the stage to shake the hand of each panelist (publisher Bennett Cerf was one). I don’t know what Louis Chu was thinking, but I see that rascal twinkle in his eye and I like to imagine he’s thinking in Toishanese.

Louis Chu’s Chinese name is Louie Hing Chu. Did the immigration official on Ellis Island flip the name, making Chu his family name and Louie his American name?

雷霆超 Louie Hing Chu is powerful naming. Louie is the character for thunder. Hing means a clap of thunder. Chu means to transcend, to surpass. I love how louie and hing stack up the thunder, and that chu shoots it to the great beyond.

We, his literary descendants, receive Eat a Bowl of Tea with a deep bow of gratitude. Louis Chu threw us urgent, supreme thunder, surpassing all.

Read this book and feel the richness of his Toishanese. The men of the bachelor society are masters of mischief; their language-play celebrates tenacity. They are troublemakers and funmakers; they make monkey laughter out of misery. Louis Chu slips in the suffering only to make the promise of surpassing a new American truth.

Read this book of pathos and mirth.

Wow your mother. Read this book.

Then pour Louie Hing Chu a cup of tea and call him Sifu. Our Grand Master.

FAE MYENNE NG’S work has received the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, a Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Writers’ Award, a Guggenheim fellowship, and a fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center at Lake Como, Italy. Bone was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Fiction Award. Steer Toward Rock received the American Book Award. She teaches creative writing and literature at UCLA and UC Berkeley.