Читать книгу South Africa and the Transvaal War (Vol. 1-8) - Louis Creswicke - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MAJUBA

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

On Sunday, the 27th of February, Sir George Colley made his last move. During the afternoon of the previous day the General, who was a great theorist, had been cogitating some scheme which he only communicated to Colonel Stewart, and to one or two others. No sooner had "lights out" been sounded, than an order was passed round for detachments of the 58th, third battalion of the 60th Rifles, Naval Brigade, and Highlanders, to parade with three days' rations. Then the order came that the force was to form up by the redoubt nearest the main road on their left. At ten a start was made, the General and staff riding in front, with the 58th leading, followed by the 60th, and the Naval Brigade in the rear. The direction taken was straight up the Inguela Mountain. Arrived on a plateau about half-way up, the troops proceeded by a path, narrow almost as a sheep path, which winds across the steepest part of the mountain. Great boulders edged the hillside, and masses of rock hung perpendicularly above the surface of the ground. One false step and the climber would have been hurled down some thirty feet, to be dashed to pieces against the stones, or entangled in the bush. This march was conducted in strict silence, no voice being raised, and indeed not a breath more than was required for climbing expended. Men and officers, all were bent on the one great feat of mounting and gaining the summit. The march continued over loose stones, and boulders and obstacles multifarious—sometimes round wrong tracks, owing to mistakes of the guide, and sometimes over grass and glassy slopes, where a man could make progress merely by means of hands and knees. Thus the force stealthily ascended, creeping up in ones and twos, the General and staff leading the way in ever-increasing darkness and silence.

So heavy was the work of ascent that, when at last they reached the top, the troops almost dropped from exhaustion. It was this exhaustion that is said by some to have influenced the General's plans, but others declare that he was not likely so to be influenced. Instead of attempting at once to throw up a rough entrenchment, he refused to permit it, declaring that the men were already over fatigued. A slight entrenchment might have made all the difference in the sad history of Majuba, but the General gave no orders to entrench, and thus the troops were left open to the enemy.

At early dawn, on looking towards the Nek, it was obvious that a large Boer force was there congregated, while at the base of the mountain was the right flank of the Dutch camp. Gazing down from the great height which had been so perseveringly gained, all hearts warmed with a glow of triumph and of anticipation. The rocket tubes and Gatlings would soon arrive, and then those below would be awakened to the tune of the guns! From their point of vantage it seemed as though the British had the Boers at their mercy.

The hilltop of Majuba was hollowed out basinwise, and there seemed only a necessity to line the rim of it in the event of a rush from the enemy. But the suspicion that the Boers would creep from ridge to ridge, and mount the crest, never dawned on any one. In the dense darkness it was impossible to become acquainted with the nature of all sides of the hill, and the troops imagined them all to be equally impregnable.

Mr. Carter, who was there, says that at this time some twenty Highlanders stood on the ridge watching the lights of the enemy, and pointing to the camp below them, and laughingly repeating their challenge, "Come up here, you beggars." They never imagined it would be possible for them indeed to come! He further states his belief that the reason why no entrenchments were attempted was that every staff officer on Majuba felt certain "that the Boers would never face the hill—entrenchments or no entrenchments on the summit—as long as the British soldier was there." For this almost fatuous belief in their own security these gallant soldiers were destined to pay heavily.

So soon as daylight served to show our troops standing against the sky-line, the enemy began to advance at the base of the mountain. The first shot on that eventful day was fired at a Boer scout by Lieutenant Lucy of the 58th, but the General, hearing it, sent word to "stop that firing." Silence again reigned. But in the meantime the Boers were crawling cautiously up the hill after leaving their horses safely under cover. About 6 a.m. they opened a steady fire, to which the British troops responded cordially. The Boer bullets, though doubling those of the British, did little damage, as the troops were partially sheltered within the basin of the hilltop. Thus the fight continued till nine, none of the officers at that time even suspecting that the enemy would venture to "rush" their stronghold. No one was wounded, and nothing was to be seen on any side of the hill, as the Boers kept closely under cover. At this juncture many men, worn out and fatigued, laid themselves down to sleep. Suddenly Lieutenant Lucy appeared asking for reinforcements, and saying that the fire was "warming up" in his direction. Some minutes later the General, who was perpetually moving round the line, cool, collected, and calculating as ever, flashed a message to Mount Prospect camp, ordering the 60th Rifles to be sent from Newcastle to his support.

Later the General espied two Boers within 600 yards or so of him mounting the ravine, and pointed them out. He had scarcely done this when Commander Romilly fell. This gallant sailor was deservedly popular, and gloom suddenly spread over the hitherto cheerful force. Still, no one dreamed that the Boers would really get to close quarters. The first awakening came when the firing, which had been till then in single shots, poured upwards in volleys. From the sound it was evident that the enemy was much nearer than had been supposed. The Highlanders, who were facing this unexpected fusillade, were soon reinforced by the reserves which had been ordered to their assistance.

The 58th, 92nd, and Naval Brigade disappeared over the ridge to meet the enemy, and vigorously returned their fire. For one moment that of the Boers appeared to slacken; then suddenly there came a precipitate retreat of our men, the officers shouting, "Rally on the right! rally on the right!" This order was obeyed, the troops describing a semicircle and coming back to the ridge to a point at left of that from which they had been so suddenly driven. But the momentary retreat had been demoralising. At this standpoint the men had become hopelessly mixed up—sailors, Highlanders, and 58th men all in a wild melee. Over this heterogeneous mass the officers had lost their personal influence. While order was being restored the Boer firing ceased. The pause was just sufficient to allow breathing time, for they almost instantaneously reopened with redoubled vigour. Their shooting was scarcely successful, but a hail of lead from the upturned muzzles of rifles continued to traverse the thirty yards which now separated the foes. The enemy numbered only about 200, but they hoped by rapidity of fire to hold the British in check till their comrades should come to the rescue. Mr. Carter thus graphically describes what was really the last despairing effort of our men:—

"The order was given in our lines, 'Fix bayonets,' and immediately the steel rang from the scabbard of every man, and flashed in the bright sunlight the next second on the muzzle of every rifle. 'That's right!' cheerily called Major Fraser. 'Now, men of the 92nd, don't forget your bayonets!' he added, with marked emphasis on the word bayonets. It was the bayonet or nothing now, and the officer's words sent quite a pleasant thrill through all. Colonel Stewart immediately added, 'And the men of the 58th!' 'And the Naval Brigade!' sang out another officer, Captain MacGregor, I think. 'Show them the cold steel, men! that will check them,' continued Fraser, whilst volley after volley came pouring in, and volley after volley went in the direction of the enemy. But why this delay? The time we were at this point I cannot judge, except by personally recalling incidents in succession. When the bayonets rang into the rifle-sockets simultaneously with the reopening of the Boers' volleys, I felt convinced that in two minutes that murderous fire would be silenced, and our men driving the foe helter-skelter down hill. After the bayonets had been drawn and fixed, and remained fixed, our men still firing for at least four or five minutes, and no order came to 'charge,' I changed my opinion suddenly."

Here we may imagine the agony—hope, doubt, suspense—that passed like a lightning flash through the minds of all who were present.

The uproar at this time grew appalling. Commands of the officers, the crash of shot, the shrieks of the wounded, all helped to aggravate the din. Boers were fast climbing the mountain sides, and the troops, worn out and almost expended, were beginning to lose the spirit of discipline that hitherto had sustained them. The officers stepped forward boldly, sword in one hand and revolver in the other, but to no purpose. Only an insignificant number of men now responded to the command.

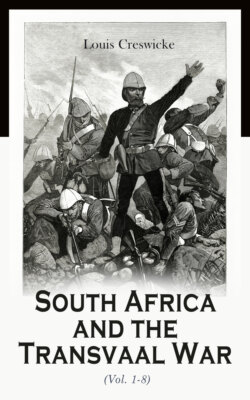

THE BATTLE OF MAJUBA HILL.

Drawn by R. Caton Woodville, from Notes supplied by Officers present.

The officer to the left, with the glass in his hand, is General Colley, who, to facilitate his ascent of the hill, took off his boots, and, during the engagement, wore only socks and slippers. He, with others, is urging the soldiers to maintain their position. The Highlander with the bandage on his face was wounded, but bravely continued to fight. The Highlander on the right, apparently asleep, was shot dead while taking aim. The officer in the immediate foreground towards the right, to whom the doctor is offering a flask, is Major L. C. Singleton, of the 92nd Gordon Highlanders, who died of his wounds. The figure pressing forward on the extreme left of the picture is the Special Correspondent of the Standard newspaper.

Mr. Carter declares that when Lieutenant Hamilton of the 92nd asked Sir George Colley's permission to charge with the bayonet, he replied, "Wait a while." Such humanity was almost inhumanity, for waiting placed at stake many lives that might have been saved. The correspondent says:—

"Evidently Sir George Colley allowed his feelings of humanity to stand in the way of the request of the young officer. We were forty yards at the farthest from the enemy's main attacking party. In traversing these forty yards our men would have been terribly mauled, no doubt, by the first volley, but the ground sloped gently to the edge of the terrace along which the enemy were lying, and the intervening space would be covered in twenty seconds—at all events, so rapidly by the survivors of the first volley, that the Boers, mostly armed with the Westley-Richards cap rifle, would not have had time to reload before our men were on them. I am not sure that the first rush of the infantry would not have demoralised the enemy, and that their volley would have been less destructive than some imagined. If only a score of our men had thrust home, the enemy must have been routed. At a close-quarter conflict, what use would their empty rifles have been against the bayonets of our men, who would have had the additional advantage of the higher ground? If the bayonet charge was impracticable at that moment, then, as an offensive weapon, the bayonet is a useless one, and the sooner it is discarded as unnecessary lumber to a soldier's equipment the better. It was our last chance now, though a desperate one, because these withering volleys were laying our men prostrate; slowly in comparison with the number of shots fired, but surely, despite our shelter. Some out of the hail of bullets found exposed victims. In a few seconds our left flank, now practically undefended, and perfectly open to the Boers scaling the side of the mountain in that direction, would be attacked with the same fury as our front.

"Looking to the spot Cameron had indicated as the one where the General stood, I saw his Excellency standing within ten paces directing some men to extend to the right. It was the last time I saw him alive."

It is unnecessary to dwell further on the tragic events of that unlucky battle. After midday our troops retreated, and the retreat soon became a rout. At this time Sir George Colley was shot. Dismay seized all hearts, followed by panic. The British soldiers rushed helter-skelter down the precipitous steeps they had so cheerfully climbed the night before, many of them losing their lives in their efforts to escape from the ceaseless fire of the now triumphant enemy.

WHERE COLLEY FELL.

ROUGH CAIRN OF STONES ON MAJUBA HILL.

Photo by Wilson, Aberdeen.

Before leaving this sad subject, it may be interesting to note a Boer account of the day's doings which is related by Mr. Rider Haggard in his useful book on "The Last Boer War":—

"A couple of months after the storming of Majuba, I, together with a friend, had a conversation with a Boer, a volunteer from the Free State in the late war, and one of the detachment that stormed Majuba, who gave us a circumstantial account of the attack with the greatest willingness. He said that when it was discovered that the English had possession of the mountain, he thought that the game was up, but after a while bolder counsels prevailed, and volunteers were called for to storm the hill. Only seventy men could be found to perform the duty, of whom he was one. They started up the mountain in fear and trembling, but soon found that every shot passed over their heads, and went on with greater boldness. Only three men, he declared, were hit on the Boer side; one was killed, one was hit in the arm, and he himself was the third, getting his face grazed by a bullet, of which he showed us the scar. He stated that the first to reach the top ridge was a boy of twelve, and that as soon as the troops saw them they fled, when, he said, he paid them out for having nearly killed him, knocking them over one after another 'like bucks' as they ran down the hill, adding that it was 'alter lecker' (very nice)."

A complete and reliable narrative of affairs on that fateful day in the ridge below Majuba was given in the Army and Navy Gazette. It is here reproduced, as it shows the finale from the point of view of an eye-witness of one of the most lamentable fights known in British history. The correspondent says:—

"As our mysterious march on the night of the 26th February began, two companies of the 60th Rifles, under the command of Captains C. H. Smith and R. Henley, were detached from General Colley's small column, and left on the Imquela Mountain. These companies received no orders, beyond that they were to remain there. The rest of the column then marched into the dark night on their unknown mission, our destination being guessed at, but not announced. The road was rough, and at some places little better than a beaten track, and the men found it hard to pick their steps among the loose stones and earth mounds. But all were cheerful and ready for their work. The ridge at the foot of the heights was reached at about midnight, and here the column made a brief halt, to allow of one company of the 92nd (which had lost its touch) coming up. Here one company of the 92nd Highlanders, under Captain P. F. Robertson, was detailed to proceed with Major Fraser, R.E., to a spot about one hundred yards distant, General Colley himself giving the order that they were to remain there, 'to dig as good a trench as time would permit of,' and further to select a good position to afford cover for the horses and ammunition, &c., that were to be left in charge of the detachment. They were also desired to throw out sentries in the direction of the camp, also a patrol of four men, with a non-commissioned officer, to watch the beaten track along which we had just come, and to act as guides for a company of the 60th Rifles expected from camp to reinforce the Highlanders on the ridge. These orders having been given, the column again moved off, leaving the Highlanders to make their arrangements.

"The men had a brief rest after their walk, and then, assisted by their officers—Captain P. F. Robertson and Lieutenant G. Staunton—began the work of making their entrenchments. At about 5 a.m. the expected company of the 60th Rifles arrived, under the command of Captain E. Thurlow and Second Lieutenants C. B. Pigott and H. G. L. Howard. Surgeon-Major Cornish also accompanied this detachment, with some mules laden with hospital requirements. Captain Thurlow, who had received no orders, and who had brought out his men without either their greatcoats or their rations, joined the Highlanders in their entrenchments. They had to work hard, so as to complete their work rapidly, and consequently the men had little or no rest that night. At about 6 a.m. we were visited by Commissariat-General J. W. Elmes, who was returning to the camp, and promised to send out the 60th their rations. Shortly afterwards a conductor named Field arrived with a led mule, laden with stores, &c., for the staff. He was hurrying on to try and reach the summit of the hill before day. Doubts were expressed as to the advisability of his going on alone; but he had his orders, he said (about the only man who had that day!), and so he went on his way. About an hour afterwards a shot was heard, and we afterwards learnt that the conductor had been wounded, and he and his mule taken prisoners! By this time the day had quite broken, the heavy curtain of the night had rolled away, and disclosed before us the rugged and precipitous ascent to the Majuba Mountain, which stood directly in front of us, about 1400 yards distant. It stood out in bold relief against a blue-grey sky, and on the summit, and against the sky, the figures of men could be distinctly seen passing to and fro. These were only discernible with the aid of field-glasses, and at that time no great certainty was felt as to their being our own men.

"Away to the south of us, in the direction of the camp, sloped the Imquela Mountain. The glasses were brought to bear on this spot also, where a man was detected signalling with a flag. The officer commanding our party (Captain Robertson, 92nd) then signalled the question, 'Who are you?' and the answer returned was, 'We are two companies of the 60th Rifles, who have been left here all night.' A second message was then sent, asking what their orders were, and the reply returned was, 'None.' Their position was consequently much the same as ours. All the morning our sentries heard occasional shots, and from time to time were seen small bodies of mounted Boers galloping to and fro near our entrenchments, seemingly to reconnoitre our position. At about eleven o'clock we were joined by a troop of the 15th Hussars, who had just come from the camp, bringing with them the rations for the 60th Rifles. This troop was commanded by Captain G. D. F. Sulivan, and accompanied by Second Lieutenant Pocklington and Lieutenant H. C. Hopkins, 9th Lancers, attached. Captain Sulivan, having received no orders, remained with our party, dismounting his men, and placing them under cover on the slope, just in rear of our entrenchment. For an hour or two afterwards all remained perfectly quiet. The distant figures on the summit of the Majuba Hill could still be seen passing and repassing against the grey sky. We had come to the definite conclusion that they were our own men, entrenching themselves on the top of the mountain. They had gained by strategy a strong position; but could they hold it? Even then the question was mooted. All at once, while we were quietly waiting, a continuous and heavy firing broke out on the mountain. We saw the blue smoke rolling across the still sky; we saw an evident stir and excitement among the party on the hill. What was it? Were they attacked, or attacking? Volley after volley rolled forth; it was a heavy and continuous fire, never ceasing for a moment. All glasses were brought to bear on the mountain, and every eye was strained to catch a sight of what was going on. After a few minutes the figure of a man hurrying down towards us was visible—a wounded man, no doubt—and a mounted Hussar was sent out to bring him in. He proved to be a wounded man of the 58th, and from him we learnt something of the disaster which had befallen our column. The General was dead, lying on his back, with a bullet through his head. Our men were nearly all either wounded or taken prisoners. The hilltop was covered with the bodies of the brave fellows, who had fought to the last. Even while he spoke we could see the desperate retreat had begun, and a few desperate figures were seen struggling down among the stones and boulders. Our men were flying, there was no doubt about that now. In a few minutes the enemy would be upon us, but we were prepared for them. I never saw men steadier or more prepared to fight, although, as I glanced round, I felt how hopeless such a fight would be. My fear, however, did not seem to be participated in by either officers or men, for Captain Robertson (the officer in command) at once began his preparation for a determined resistance. The ammunition boxes were opened, and placed at equal convenient distances all round the entrenchment. Half the entrenchment was manned by the Highlanders, and the other half by Rifles. These preparations were quietly and promptly made. The men were silent, but steady. Looking round, every face was set with a grave determination 'to do,' and there was not a word audible as the orders were spoken and the commands obeyed. The low (and to an experienced eye) fragile turf walls that were to offer shelter seemed but poor defences, now that they were to be tried. They were only about four feet high by two feet thick, with one exit at the rear, and could never have stood before a fire such as was even now pouring down the slope of Majuba. The wounded were now being brought in rapidly by our mounted Hussars, who did their work steadily. Some of the poor fellows were terribly wounded, and though Surgeon-Major Cornish did his best for them unassisted, many had to lie unattended to in their suffering. All brought the same bitter news of defeat and annihilation, not very reassuring to our little force, which was now about to take its part in the day's engagement. As suddenly as it began, the firing as suddenly ceased; and we knew that the dreadful task of clearing the heights was done, and our resistance about to begin. We could see the Boers clustering like a swarm of bees at the edge of our ridge. Every moment we expected a rush and an attack. But they hesitated. They were waiting—waiting for the party of some 600 or 700 mounted Boers, who presently appeared upon our left flank. Our entrenchment was now almost surrounded. The mounted Boers were the first to attack us on our left flank, and their fire was spiritedly replied to by the Rifles. At this moment, and while we were actually engaging our enemy, the order came from the camp desiring Captain Robertson to retreat his force without delay. No such easy matter now, for the order came almost too late; the Boers were within easy range of us, and determined to attack. Nevertheless, in the same orderly and steady manner in which the preparations for defence had been made, the preparations for retreat were begun. Much credit is due to Captains Robertson and Thurlow for the energetic manner in which they helped to load the mules, securing a safe retreat for the ammunition and stores, and then assisting Surgeon-Major Cornish to get off the wounded. All this time we were under fire, and it was while retreating that poor Cornish was killed. When our little entrenchment had been cleared of its stores, the real retreat began, made under a murderous fire, which followed us as we hurried down the steep slope into the ravine below. Captain Sulivan, with his troop of Hussars, was placed on the right flank to try and cover the retreat in that direction. By this time the Boers had partially occupied our entrenchment, having broken down its defences easily enough. And we had scarcely retreated down the steep slope and into the ravine before they occupied the ridge above us in hundreds, sending volley after volley after our retreating men. It was a case now of sauve qui peut, and to me the only marvel is how we lost so few under the circumstances. Our casualties were four killed (including Surgeon-Major Cornish), eleven wounded, and twenty-two prisoners. The Highlanders suffered the most. The officers were the last to leave the ridge. I saw Captain Robertson standing on the crest of the slope giving some final directions just a moment before the ridge was entirely covered by the Boers, and his escape consequently was almost a miraculous one. I was in the ravine before I heard our artillery open fire upon the Boers. Second-Lieutenant Staunton, 92nd Highlanders, was taken prisoner. We were never joined by the two companies of the Rifles who were left on the Imquela Mountain the night before, nor did I see them under fire at any part of the day. Thus ended our brief battle, and only those who took part in it can tell the bitterness of having to retreat, utterly routed and defeated as we were."