Читать книгу Pacific Seaweeds - Louis Druehl - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

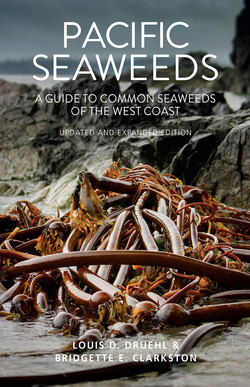

ОглавлениеPacific Seaweeds

14

marshes above the high tide line. We are excited to include shore plants as a new addition to Pacific Seaweeds.

Seaweed Morphology and Growth

The form and development of a seaweed, its morphology, begins with the basic compartmental unit of life: the cell. The cell contains those structures necessary for life: nucleus, chloroplast (responsible for photosynthesis), mitochondrion (responsible for the release of chemically bound energy) and others. Among the algae, seaweeds included, there is little cellular differentiation relative to land plants. The cells of seaweeds may be classified as parenchyma, meaning they are surrounded by thin cell walls with little or no secondary thickening and they usually retain their ability to undergo cellular division throughout their lives. Land plants have parenchyma, collenchyma and sclerenchyma. These latter cell types are characterized by secondary cell wall thickenings, resulting in woody characteristics, and by their inability to divide after reaching maturity.

Seaweed cells are differentiated by the number of nuclei they contain, their association with adjacent cells and their function. The cells may be multinucleate or uninucleate. Generally, cells visible to the naked eye are multinucleate (e.g., Urospora, p. 53). Cells are usually separated from adjacent cells by a well-defined end cell wall. During cell division, this cell wall grows as an expanding plate, separating the two daughter cells so that there is limited connection between them. In some seaweeds, the end cell wall is produced when the existing cell wall grows inward, effectively pinching the cell into two daughter cells. There is expanded connection between these cells, which are called coenocytic cells. They are usually multinucleate and may be very long (30 cm/12 in Codium, p. 68).

The surface cells of fleshy seaweeds are responsible for photosynthesis and nutrient uptake. The inner cells serve as packing and may form storage and/or primitive conducting tissues. Some cells are responsible for attaching the seaweed to its substrate (no small task). In some seaweeds, such as the green alga Ulva (p. 62), almost any cell may become reproductive; but in others, including many red seaweeds, only specific cells become reproductive. Similarly, cells that can undergo frequent division, thus being primarily responsible for growth, may be localized or occur generally throughout the plant.

Seaweeds grow in three basic ways. In the simplest way, called diffuse growth, cells divide more or less randomly all over the body. Take Ulva,