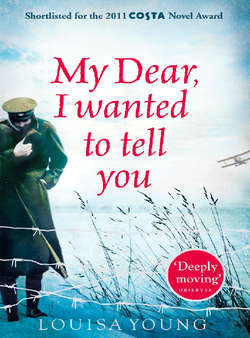

Читать книгу My Dear I Wanted to Tell You - Louisa Young - Страница 11

ОглавлениеChapter Six

London, August 1915

The letter, the first since the Christmas card, was sent on by her mother, with a note on the back in swirling, elegant writing: ‘Have you an admirer? Tell all!’

Not likely. Not after the look on your face when you gave me the first letter, the oh-Nat-I’m-just-going-to-war-’bye-then letter. The stupid stupid stupid unkind letter. Not after you said: ‘It’s probably for the best, darling. I know you liked him but you know he’s not the sort of boy . . .’

Oh yes he is the sort of boy, he is EXACTLY the sort of boy. He is THE boy.

Liked. In the past. Thanks for that little extra, Mother.

Followed by the Christmas card which might as well have been from someone’s uncle they hardly knew . . .

Nadine was not able to say, either to her mother or to herself, that her mother was wrong and she was right and Riley was everything, everything he should be. Because he wasn’t. He was – he had somehow turned into – someone to whom she could only write those stupidly cheerful notes. If she could write at all. Was it distance? Was it the fact of words on paper, uncomfortable, unchangeable? Was it whatever had happened that had made him leave so suddenly? Was it whatever was happening out there, which she couldn’t ask about, which he wasn’t writing to her about?

But that moment, in the studio, when he had turned to her, and she had turned, and there was that moment when she had thought, for a second of absolute bewildering thrill, that he was going to kiss her, and he hadn’t but he had put his hand . . . and that moment when they had looked at each other, and then, just then, for that moment . . . wasn’t he everything? Wasn’t it all true, just true, and possible, and true?

Like the Donne . . . eye beams twisting . . .

And Papa had said, There’s nothing you can do about it . . .

And the heart was true, and the heat, in that moment, with his hand on her waist and that big old pinafore, the hyacinth smell, that morning, was a promise. They had made a promise then. They had. They had. That touch, that surge, that look.

The entire autumn, no one mentioned him to her. She had wanted to ask. She had lain in bed wondering who best to ask, going round in circles. And when she had asked, she learnt nothing. Her family had heard nothing from him. Sir Alfred had had only a card when Riley was in training. She had asked Terence, who had rather embarrassedly said, no, he hadn’t heard from the old boy. She had been tempted to visit Mrs Purefoy – she had even got her coat on to go to their house – but having already written for his address she grew embarrassed; overcoming the embarrassment she couldn’t find the street; having found the house she grew embarrassed again at its smallness, so she decided to write after all; and having written she received no reply; and thus ignored she retreated into humiliated confusion and did not know what to do.

During a drawing lesson in the studio she had braved the topic again with Sir Alfred. (Thank God her parents had got over their moment of concern about her studying art, for now at least.) ‘I wonder if there is any news of Riley,’ she said. ‘I suppose he would have written to you. Or his mother.’

‘The Paddingtons are in France, I believe,’ said Sir Alfred. ‘Or perhaps Flanders. If he’d talked to me, I would have put in a word for him with the Artists’ Rifles.’ He turned away, and the broad old back said clearly: Enough. Don’t ask.

So instead she had grown paler and thinner, and began swarming inside, as every possibility, every nightmare, every story in every newspaper, every bad thing that could happen was happening, in her mind, to him. Every single bad thing.

Jacqueline, as Christmas passed and the war was not over, noticed her daughter’s decline. ‘Go to Scotland, darling,’ she said. ‘Stay with Uncle George. Get some fresh air.’

‘I’d much rather go to art school, Mother. To the Slade.’

Jacqueline closed her eyes for a moment, annoyed. ‘We’ve talked about this,’ she said.

‘It’s what I would like to do,’ Nadine said politely. ‘It’s what I am good at.’

‘It’s not suitable,’ said Jacqueline, with a little tightening in her face, annoying Nadine, who knew that her mother had sat for plenty of artists in her youth. Jacqueline glanced at her daughter, saw the retort in her eyes, and cut it off. ‘And you’re not good enough,’ she said.

‘Who says?’ Nadine replied, stung. This was a new tack from her mother. She was good.

‘Sir Alfred,’ lied Jacqueline. A girl needs a good reputation, these days more than ever. Art school is for times of peace and plenty, not for unmarried girls in wartime.

Nadine held her head very high, and blinked. She didn’t believe it. Sir Alfred knew she had enough talent to invest in. He didn’t think a girl could have a career as an artist, but he didn’t deny talent when he saw it . . .

For a moment Jacqueline wavered, looking at her proud daughter, then steeled herself. It’s for her own good.

Nadine looked at her arms, thinner than ever, and her narrow feet. What was the point of a female? Even at the best of times, let alone during war? All she wanted was art and love . . . Like Tosca, she thought, with a little laugh. And love was – well, denied. And art too. Her cousin Noel had said to her, on his most recent visit, that he felt less than a man because his asthma prevented him being Over There. Well, she felt less than a woman. At least a man knew he was meant to be a soldier, and a boy knew he was meant to be a man. But she – she was too young to have found out the point of herself anyway, and now she was shipwrecked, stranded in time. Not a woman, not a girl any more, and not, apparently, an artist.

Scotland?

No.

‘Then I’m going to join the VAD,’ she said blandly. ‘I’m going rather mad here, knowing there is so much to do and not doing anything. I have been reading all about it. I shall take all my frustration out on sheets.’

‘No,’ said Jacqueline, immediately, instinctively.

‘Well, I must do something, Mama. I think that’s a fair choice, the Slade or the VAD.’

But Jacqueline could only see it as men, or more men. Artistic, immoral men, with attractively long hair and no prospects, or broken, heroic, half-naked men in desperate need . . . Getting Riley out of the way was one thing, but there were always more men: wrong ones, new ones, ones outside the systems of safety . . . Lord, she thought, it used to be so much fun playing with fire, back when everything was safe.

The wounded, she decided, would be less attractive to her daughter than the artists.

*

While scrubbing, boiling, lugging, hanging, pouring, twisting and folding made up most of Nadine’s duties at London General Number 2, Chelsea, the reality of blood and flesh was also available to her, and she saw it. It was a shock, and she was by no means sure at the beginning that she would be able to stay in the hospital. To strengthen her nerve, she blackmailed herself, imagining that each boy was Riley, and she was some French or Belgian girl. Each shattered leg she saw became his leg; each twisted arm was his arm; each pale and sweaty brow was his handsome brow; each gunshot wound settled itself into his flesh. It both brought her closer to them and protected her from them. But what started as a spur and a naturally arising technique of self-protection developed with pandemic haste into a morbid, almost-constant fantasy about the terrible things that might be happening to him.

Jean, older and wiser, with reddened knuckles and a pot of rouge number two in her bag, said to Nadine, over biscuits and Bovril, one carbolic-scented night-shift, ‘You’re ill-wishing him. Don’t. God didn’t give you an imagination so you could use it to worry all the time.’

So Nadine saved Riley’s letter till Jean was not there. It burnt in her apron pocket. But, oh, the circumstances of the letter faded into nothingness at its contents. He might as well have leapt out of the envelope in person, telling her everything as clearly as he always had, which now were these impossible things, these things that swept her every previous concern to the eight winds. He hadn’t written? Oh, diddums. He had gone away? Poor little you.

I don’t exist.

How can that be? She read it again.

Is it so bad that there is no room in the same dimension of creation for both it and him, and that as it is all-powerful, he must cease to exist?

That’s the wrong way round, surely. Surely it must cease to exist, because he, palpably, does . . . It. It. A gigantic amorphous It, and a little speck of warm flesh and blood standing in front of It, in the middle of It, fading away.

She thought of his eyes and his mouth, his jokes and his intensity. She remembered him up the tree, popping out from among the sun-spattered chestnut leaves, their sharp folds. She thought of that first snowball, and his black curly hair, like hers but different, and how even then she had liked how he was like her but different. She pictured a little brain and a little heart buffeted to and fro inside a cloud of smoke and flash and shrapnel. She remembered the hardness of the wood of the trestle table under her thighs, bare legs for the spring day, the moment like lightning, when a link had flashed awake, body mind heart, and for the first time she had felt herself connected to herself.

*

My dear Riley,

What can I say to you now? I only want to say what will help to make you stronger and perhaps happy, but at the same time, if you don’t exist, then you won’t want to hear from me at all, as I will only remind you that you do exist, with a past and a future and people who love you, but then you know at heart that you do – but if you find it better for now to put away that knowledge then perhaps this isn’t the moment to mention it, so I won’t . . . but I WON’T send you a letter of ‘hope this finds you as it leaves us and Mother and Father send their regards’ . . . not to scorn the people who do that . . . and of course Mother and Father do send their regards, or at least I’m sure they would if I ever saw them, at least, Father would, though Mother would say – actually not say, just look, that I shouldn’t be writing to you at all – she has become more and more proper since the War began, unlike everybody else who does exactly the opposite – she lives in fear of chaos and freedom, which she thinks are the same thing, and much more dangerous than the Hun. She is hardly artistic at all any more and has taken to wearing stays again, just when everybody else is giving them up – goodness, how she would disapprove of my mentioning that – but I only see them once a week now if that and I’m not waiting till next week to write back to you just to be able to send their regards. Reading back, that doesn’t quite make sense but I think you will see what I mean.

Riley, I was so happy to hear from you, so utterly happy that I sang on the ward, and Sister gave me such a look and asked, so I had to tell her that I had had good news, that someone I feared might be lost was not lost after all – because for all you say you don’t exist and for all I respect that and your reasons for having to think it, Riley, you do! Riley exists! And that alone, dear Riley, makes me so happy that I sing. Oh, now I’ve done it –

But surely it is the really existing which will keep you sane for after it’s all over? We’ve had some shell-shock cases in here and oh, Lord, Riley, I don’t know how anyone can decide which needs to be fixed first, their broken limbs and wounds or their broken minds. I can tell you what I do: an awful lot of washing and cleaning. Piles of sheets that would stretch to Paree, dreams of wading through Keatings and Lysol . . . But I have two special talents: first, I speak French. So sometimes I am called from cleaning to speak French or translate something, though more often it’s talent number two: I don’t faint at blood. So I am called on to help clean up in the operating theatre, and I have seen such sights – my God, Riley – well, you will have seen them too, and at closer quarters. Why do I tell you this? Because I want you to feel a bit less alone. And it can’t go on much longer. Governments will just have to take a look at the hospitals and see straight, at what is happening, and they’ll stop.