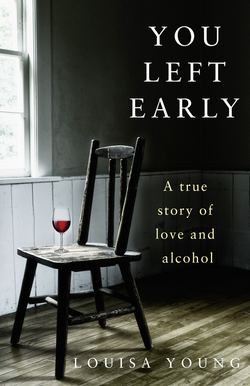

Читать книгу You Left Early: A True Story of Love and Alcohol - Louisa Young - Страница 7

Introduction 2017

ОглавлениеThe book you hold in your hand is a memoir by me, Louisa Young, a novelist, about Robert Lockhart, a pianist, composer and alcoholic, with whom I was half in love most of my adult life and totally in love the rest of it. It’s as much about me as about him, and is of necessity a difficult book to write. So why am I writing it? Why expose, so openly, chambers which are only usually displayed via the mirrors and windows with which novelists protect their privacy?

Because his life is a story worth telling.

Because our love story, while idiosyncratic, is universal.

Because alcoholism has such good taste in victims that the world is full of people half or totally in love with alcoholics – charismatic, infuriating, adorable, repellent, self-sabotaging, impossible alcoholics – and this is hard, lonely, baffling, and not talked about enough.

Because although there are a million and a half alcoholics in Britain, many people don’t really know what alcoholism is.

Because alcoholics also love.

Because I don’t want to write a novel about an alcoholic and a woman; I want to write specifically about that alcoholic, Robert, and this woman, me.

Because everything I have ever written has been indirectly about Robert, and the time has come for me to address him directly.

Because the last time I tried to address it directly I told him, and he said, ‘You won’t be able to finish this until I’m dead.’

Because I have realised that for me, quite the opposite: he won’t be properly dead until I’ve finished it.

Four months after he died, I wrote this:

It can’t be surprising that I can’t write now. All I can think about is Robert and death, so that is all I could write about, but I can’t. To write Robert would be to seal him. I, who can rationalise my life into any corner of the room and out again and rewrite my every reality in any version I like, and back, twice before lunch, I cannot pin that man to the specimen paper. I cannot claim to have all of him in view at one time. I cannot slip him into aspic, drown him in Perspex, formalise him – look, there he is in that frame, that’s how he was, that’s him. No, that is not him. He is an alive thing. His subtleties and frailties are living things. I cannot bind to myself or any other place the joy that he was. It makes no sense to me for him to be dead. And when it does make sense to me, as no doubt it must at some stage, then – well then he is even deader, because I will have accepted it. And I do not accept it. I do not want to accept it. I reject it. I say to death: Fuck off.

But I am a writer, and without writing I was bereft. And God knows I was bereft enough already. I have so much and yet these have been years of loss. Each loss lost me something else as well. Losing Robert lost me writing. I wanted to talk to him about it. Instead there I was, writing about not being able to write: If I write this book, am I preventing other versions? Will making this our conversation disbar me from remembering other things we said? Am I bruising my memories by handling them? If I file them, will I ever find them again? Will their bloom be intact?

I was always terrified of losing him; I lost him a hundred times and had him back. I wanted him back yet again. His nine lives, the nadirs he specialised in. I thought: he wouldn’t really be dead. It’s so unlike him.

This is my version. Anyone who knew him will have their own version. I understand that. I’ve done my best to balance open honesty about this illness with sensitivity.